Abstract

We examined the impact of treatment with fish oil (FO), a rich source of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA), on white matter in 37 recent-onset psychosis patients receiving risperidone in a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Patients were scanned at baseline and randomly assigned to receive 16-weeks of treatment with risperidone+FO or risperidone+placebo. Eighteen patients received follow-up MRIs (FO,n=10/Placebo,n=8). Erythrocyte levels of n-3 PUFAs eicosapentaenoic acid(EPA), docosahexaenoic acid(DHA), and docosapentaenoic acid(DPA) were obtained at both time points. We employed Free Water Imaging metrics representing the extracellular free water fraction(FW) and fractional anisotropy of the tissue(FA-t). Analyses were conducted using Tract-Based-Spatial-Statistics and nonparametric permutation-based tests with family-wise error correction. There were significant positive correlations of FA-t with DHA and DPA among all patients at baseline. Patients treated with risperidone+placebo demonstrated reductions in FA-t and increases in FW, whereas patients treated with risperidone+FO exhibited no significant changes in FW and FA-t reductions were largely attenuated. The correlations of DPA and DHA with baseline FA-t support the hypothesis that n-3 PUFA intake or biosynthesis are associated with white matter abnormalities in psychosis. Adjuvant FO treatment may partially mitigate against white matter alterations observed in recent-onset psychosis patients following risperidone treatment.

Keywords: Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Free Water Imaging, White Matter, Docosahexaeonoic Acid, Docosapentaenoic Acid, Antipsychotics, Psychosis

1. Introduction

There is considerable evidence implicating cerebral white matter abnormalities in the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders (Kelly et al., 2017; Nortje et al., 2013; Tkachev et al., 2003; Uranova et al., 2007). Studies utilizing diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) have consistently reported lower fractional anisotropy (FA), a putative measure of white matter microstructure, in both early- and late-stage patients with psychotic illnesses compared to healthy volunteers (Kelly et al., 2017; Nortje et al., 2013; Wheeler and Voineskos, 2014). Lower FA has been proposed to reflect alterations in the myelin sheath, a conclusion supported by post-mortem histological analyses in patients with schizophrenia that report an overall reduction in the number of oligodendrocytes (Chew et al., 2013; Segal et al., 2007) and reduced expression of myelin-related genes (Hakak et al., 2001). Recent work also indicates that excessive or chronic pro-inflammatory activation may be a key contributor to white matter pathology in psychosis. In this model, it is proposed that prolonged exposure to immune-related factors, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines, may result in the deterioration of cerebral white matter (Bennet et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2015). There is a significant body of data supporting this mechanism (Coughlin et al., 2016; Najjar and Pearlman, 2015; Perkins et al., 2014; Prasad et al., 2015), including several studies finding that pro-inflammatory markers, such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), are elevated in patients who transitioned to psychosis (Fillman et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2011; Trépanier et al., 2016; van Kesteren et al., 2017). The evidence for these two, potentially linked, pathologies has led to an increased focus on the identification of therapeutic agents that may jointly protect or promote myelin health, in addition to attenuating inflammatory processes.

Fish oil (FO) is a rich source of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, C20:5:n-3), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA: C22:6n-3), and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA, C22:5:n-3). Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA: 18:3:n-3), the short-chain precursor of long-chain n-3 PUFAs, is considered “essential” because humans cannot manufacture it de novo and it must be obtained from the diet, n-3 PUFAs have several important physiological functions in the brain including energy storage/production, gene expression, and, most importantly, the production and maintenance of myelin (Liu et al., 2015; Ozgen et al., 2016). n-3 PUFAs are an important component of the phospholipid bilayers of oligodendrocyte membranes that form the myelin sheath surrounding axons (Ozgen et al., 2016). Several cross-sectional and prospective imaging studies have found that higher n-3 PUFA intake and/or blood levels are associated with larger regional white matter volumes in healthy human subjects (McNamara et al., 2017). Furthermore, supplementation with FO for twenty-six weeks led to increased FA in several major white matter tracts in a DTI study of healthy older adults (Witte et al., 2014). Preclinical in vitro and animal studies also indicate that n-3 PUFAs are associated with attenuated activation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines from activated microglia (Shi et al., 2016; Zendedel et al., 2015). Taken together, these findings suggest that n-3 PUFAs may play a role in the suppression of inflammatory processes and the promotion of myelin maintenance.

Prior cross-sectional studies have reported lower blood levels of DPA, DHA, and EPA in patients with schizophrenia spanning the illness spectrum (Peters et al., 2009a; 2013a; Reddy et al., 2004; van der Kemp et al., 2012), supporting the hypothesis that disturbances in PUFA metabolism or dietary insufficiency may contribute to white matter changes in psychotic disorders (Horrobin, 1998). Some clinical trials demonstrated that n-3 PUFA administration can be beneficial for individuals with psychotic symptoms, although findings have been more consistent in first-episode and recent-onset schizophrenia compared to multi-episode schizophrenia (Chen et al., 2015). Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) studies have also demonstrated that erythrocyte n-3 PUFA levels were positively correlated with white matter FA in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia (Peters et al., 2013a; 2009a).

Traditional dMRI methods and metrics (e.g., FA) cannot distinguish between changes in the diffusion signal that could be the result of pro-myelinating or immune-related pathways, both of which are possible when investigating the effects of PUFAs (Pasternak et al., 2018). Free Water Imaging is a dMRI-based processing technique that can provide more biologically-specific metrics of white matter microstructure than traditional DTI (Lyall et al., 2018; Pasternak et al., 2009; 2012) by deconstructing the diffusion signal into two compartments. One is the free water compartment, which is quantified by the free water fractional volume (FW) metric representing the amount of isotropically diffusing, unrestricted extracellular water within each voxel. FW is sensitive to biological pathologies affecting the extracellular space, such as edema or atrophy (Di Biase et al., 2019; Lyall et al., 2018; Pasternak et al., 2012). The second compartment, the tissue compartment, is quantified by tissue-specific FA (FA-t), which represents the amount of hindered or restricted water diffusion. FA-t more closely reflects tissue-related processes related to white matter health (e.g., axonal integrity or myelination) than FA (Pasternak et al., 2009) as it is not contaminated by potential extracellular pathologies.

This study examined the potential impact of adjuvant FO treatment on white matter microstructure in recent-onset psychosis patients treated concurrently with risperidone in the context of a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial (NCT01786239 registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov). DMRI scans and peripheral erythrocyte n-3 PUFA measures were collected at the onset of treatment and again following 16 weeks of controlled treatment with either risperidone + placebo or risperidone + FO. We investigated whether changes in white matter microstructure following FO treatment were associated with extracellular changes potentially indicative of immune activation and/or with cellular changes potentially indicative of changes in myelin health. Our primary outcome measures included the Free Water Imaging metrics, FA-t and FW, as well as the traditional DTI metric, FA, for comparison with previous work. We tested the hypothesis that n-3 PUFA erythrocyte levels would be positively correlated with white matter FA-t at the onset of treatment. Based on prior work demonstrating FA reductions in association with antipsychotic treatment (Meng et al., 2019; Szeszko et al., 2014), we also predicted that patients treated with risperidone + FO would demonstrate higher FA-t and lower FW compared to patients treated solely with risperidone.

2. Materials And Methods

2.1. Clinical Trial Overview

The clinical results of the double-blind trial have been reported previously (Robinson et al., 2019). Briefly, all participants received open-label risperidone and all were randomly assigned adjunctive FO or placebo in a double-blind manner. Randomization to risperidone + placebo vs. risperidone + FO was conducted on a 1:1 basis stratified by sex and length of antipsychotic exposure (< versus ≥16 weeks) by the study biostatistican using a computer generated randomization list. Study participants, and staff providing treatment and accompanying patients for MRI scans were blind to randomization.

The FO and matching placebo (a soybean/com blend) capsules were identically colored and flavored with natural lemon-lime to protect the blind (Ocean Nutrition Canada). Each FO capsule contained 370 mg EPA and 200 mg DHA as well as 2 mg/g tocopherol. The dose was selected to be comparable to that used in the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (Cadenhead et al., 2017). Participants took one randomized capsule in the morning and one capsule in the evening so that the total daily dose was 740 mg of EPA and 400 mg of DHA. If participants were receiving an antipsychotic prior to study entry, it was terminated and risperidone initiated. The initial dosing schedule for risperidone was: 1 mg qhs days 1-3, 2 mg qhs on day 4 and 3 mg on day 7 and could be increased up to 6 mg, if needed until participants responded or side effects precluded further increases.

2.2. Subjects

Thirty-seven (28M/9F) patients (mean age = 21.8, SD = 5.2) were recruited from the Zucker Hillside Hospital, a large acute care non-for-profit psychiatric facility in New York, scanned at the onset of treatment and then randomly assigned to receive 16 weeks of treatment with either risperidone + FO or risperidone + placebo. Data were collected from June 2013 to September 2015. All patients received a physical exam and laboratory screening to rule out medical/neurologic causes for their psychotic episode. Fourteen patients were antipsychotic drug-naive at the time of the scan. For the remaining 23 patients, the mean lifetime days of antipsychotic treatment prior to study entry was 16.7 (range = 0 to 240) and the median number of days was 3. Eighty-six percent of participants had taken antipsychotics for 14 days or less in their lifetime. Age at first psychotic symptoms was 20.0 (SD = 5.5) years. Patients had a mean education of 12.3 (SD = 2.2) years and mean total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale score (BPRS) (Woerner et al., 1988) at the time of the baseline scan was 42.1 (SD = 7.2).

Inclusion criteria were: 1) current DSM-IV-defined diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID-I/P) (First et al., 1996); 2) does not meet DSM-IV criteria for a current substance-induced psychotic disorder, a psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, shared psychotic disorder, or major depressive disorder with psychotic features; 3) current positive symptoms rated ≥4 (moderate) on one or more of these BPRS items: conceptual disorganization, grandiosity, hallucinatory behavior, unusual thought content; 4) in an early phase of illness as defined by having taken antipsychotic medications for a cumulative lifetime period of ≤ 2 years, 5) age 15 to 40 years; 6) competent and willing to sign informed consent; and 7) for women, negative pregnancy test and agreement to use a medically-accepted birth control method.

Exclusion criteria for all participants were; 1) serious medical condition or treatment known to affect the brain; 2) other treatment with a medication with psychotropic effects; 3) significant risk of suicidal or homicidal behavior; 4) cognitive/language limitations, or other factors precluding informed consent; 5) medical contraindications to treatment with risperidone , n-3 PUFA supplements or placebo capsules; 6) lack of response to a prior adequate trial of risperidone; 7) taking FO supplements; and 8) MRI contraindications.

Patient diagnoses were supplemented by information from clinicians and, when available, family members and included schizophrenia (n = 27), schizophreniform disorder (n = 6), schizoaffective disorder (n = 1), or bipolar disorder (n = 3). The study was approved by the Northwell Health Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals, and from a parent or legal guardian in the case of minors. Written assent was obtained from all minors.

2.3. Erythrocyte Fatty Acid Composition

Whole venous blood was collected into EDTA-coated BD Vacutainer tubes and centrifuged for 20 min (1,500 xg, 4°C) using methods described previously (McNamara et al., 2013). Briefly, plasma and the platelet rich interface were removed, and erythrocytes washed three times with 0.9% saline and stored at −80°C. Fatty acid composition (mg fatty acid/100 mg fatty acids) was computed by a technician blind to group assignment and used as the dependent measure. Blood was collected for all subjects (except 2) prior to the baseline MRI scan. The remaining 2 patients had blood collected the day following the MRI exam.

2.4. MR Imaging Acquisition and Processing

DMRI scans were acquired at the North Shore University Medical Center on a General Electric 3T HDx scanner (Milwaukee, Wisconsin). An echo-planar imaging sequence was implemented with the following parameters: TR = 14000 ms, TE = 75 ms, 51 contiguous 2.5 mm slices, matrix = 128 x 128, field of view = 240 mm, 5 images without diffusion weighting (b = 0 s/mm2) and 31 images with non-collinear diffusion-encoding gradients applied with b = 1000 s/mm2. These images were corrected for motion and eddy-current artifacts and masked to exclude non-brain areas utilizing 3D Slicer (Norton et al., 2017). A relative-motion parameter was calculated to exclude subjects with high motion (> 2 SD from mean, n = 2) (Ling et al., 2012). After pre-processing and quality control steps, the Free Water Imaging analysis was applied as described previously (Lyall et al., 2018; Pasternak et al., 2012; 2009). Briefly, the motion and eddy-current corrected images were fitted to a two-compartment model comprising a free water compartment from which the FW measure is derived, and a tissue compartment modeled as a tensor from which the FA-t measure is derived. Traditional DTI voxel-wise FA maps were also created for comparison purposes. FW and FA-t served as the primary outcome measures whereas FA was a secondary outcome measure.

We utilized the tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS; (Smith et al., 2006)) pipeline along with the FA target image and skeleton that were created by the Enhanced Neuroimaging Genetics by Meta Analysis (ENIGMA) DTI Working Group at the University of South California, all of which are publicly available online (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/ongoing/dti-working-group). FA, FA-t, and FW values were projected onto the ENIGMA skeleton. To assess changes between baseline and follow-up scans, we calculated within-subject difference maps of the resulting white matter skeletons for each diffusion measure using “fslmaths” (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/Fslutils).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY:IBM Corp.). We used either independent groups t-tests or chi-square analyses to compare demographic and clinical variables (age, sex, education, handedness, age at first psychotic symptoms, baseline BPRS scores, and the number of weeks between the scan timepoints) between groups. Repeated measures analysis of variance was used to assess changes in n-3 PUFA levels across time. In these analyses group (risperidone + placebo vs. risperidone + FO) served as a between subjects factor. Time (baseline and follow-up) and n-3 PUFA (DHA, DPA, and EPA) levels were the respective within subjects factors in separate analyses. We used the Greenhouse-Geisser correction to correct for degrees of freedom. Follow-up analyses were conducted using either independent or paired sample t-tests. Alpha was set to 0.05 (two-tailed).

Group comparisons of the diffusion measures and correlations of the diffusion measures with n-3 PUFA erythrocyte levels were performed using a nonparametric permutation-based test (Winkler et al., 2014) with a threshold-free cluster enhancement and family-wise error correction (Smith and Nichols, 2009). For each contrast 5000 permutations were performed, resulting in statistical maps that are corrected for multiple comparisons across the whole skeleton, with significance at a threshold of p < 0.05. Age, sex, and motion were included as covariates in the permutation testing for the cross-sectional two-sample t-tests at baseline and follow-up, as well as for all correlations. Age and sex were included as covariates for all tests performed on the difference maps between baseline and follow-up.

All of the following analyses were conducted using FSL Randomise (Winkler et al., 2014). Baseline DHA, DPA, and EPA erythrocyte levels were correlated with FA, FA-t and FW to investigate whether n-3 PUFA concentrations at study entry were related to white matter diffusion metrics across the entire sample. We conducted independent groups t-tests to investigate between-group differences in the diffusion metrics at baseline and follow-up. Two-sample t-tests were also performed on the difference maps for FA-t, FW, and FA to determine if there were differences in the amount of change between groups. To investigate within-group longitudinal changes in diffusion measures, we performed one-sample t-tests on the difference maps of FA-t, FW, and FA for the two groups, separately.

3. Results

3.1. Final Dataset

Thirty-seven patients participating in the clinical trial had baseline MR imaging exams and n-3 PUFA erythrocyte data available for analysis. Of these 37 patients, 18 received follow-up MR imaging exams after participating in the clinical trial with 10 patients assigned to risperidone + FO and 8 patients assigned to risperidone + placebo. Of the 18 patients with 16 week follow-up MR imaging scans, 2 did not have 16 week follow-up n-3 PUFA data available (1 had received FO and the other placebo). Sixteen-week follow-up n-3 PUFA data were available for 20 of the 37 patients with baseline MR imaging exams and of these 20 patients 4 did not have 16 week follow-up MR imaging exams (1 had received FO and 3 had received placebo).

3.2. Demographics

Demographics for the entire sample at the time of the baseline scan are provided in Table 1. There were no significant differences between individuals assigned to risperidone + placebo vs. risperidone + FO in the total number of days of antipsychotic exposure prior to the MRI scan. There were no significant differences between individuals who received a follow-up scan compared to individuals who did not receive a follow-up scan in distributions of age, sex, education, handedness, age at first psychotic symptoms or total BPRS score. There were no significant differences between the risperidone + placebo and the risperidone + FO groups at the time of the follow-up scan in distributions of age, sex, education, handedness, age at first psychotic symptoms, number of weeks between the scan timepoints or any baseline BPRS scores.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics for Patients Receiving a Baseline and Follow-Up DTI Scan.

| Baseline DTI (n = 37) | Follow-Up DTI (Risperidone + Placebo; n = 8)1 | Follow-Up DTI (Risperidone + Fish Oil; n = 10)1 | Test Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age | 21.8 (5.2) | 22.0 (4.6) | 20.6 (3.6) | t = 0.65 | 0.53 |

| Sex (M/F) | 28/9 | 8/0 | 7/3 | X2 = 2.88 | 0.09 |

| Mean Education (years) | 12.3 (2.2) | 11.4 (2.3) | 12.3 (2.1) | t = 0.73 | 0.48 |

| Handedness2 (R/L) | 26/11 | 6/2 | 7/3 | X2 = 0.06 | 0.81 |

| Mean Age (years) at First Psychotic Symptoms | 20.0 (5.5) | 19.9 (4.0) | 18.8 (4.2) | t = 0.55 | 0.59 |

| Mean Total BPRS at Baseline | 42.1 (7.2) | 42.75 (6.0) | 42.6 (6.1) | t = 0.05 | 0.96 |

| Mean Number of Weeks between Scans | --- | 16.5 (1.1) | 16.6 (.79) | t = −0.34 | 0.74 |

Notes:

There were no significant group differences in demographics between individuals assigned to risperidone + placebo versus risperidone + fish oil; standard deviations in parentheses;

Using previously published criteria, 26 patients were categorized as dextral and 10 patients as nondextral (Oldfield, 1971). One subject was categorized as nondextral based on hand preference alone.

3.3. n-3 PUFA Changes

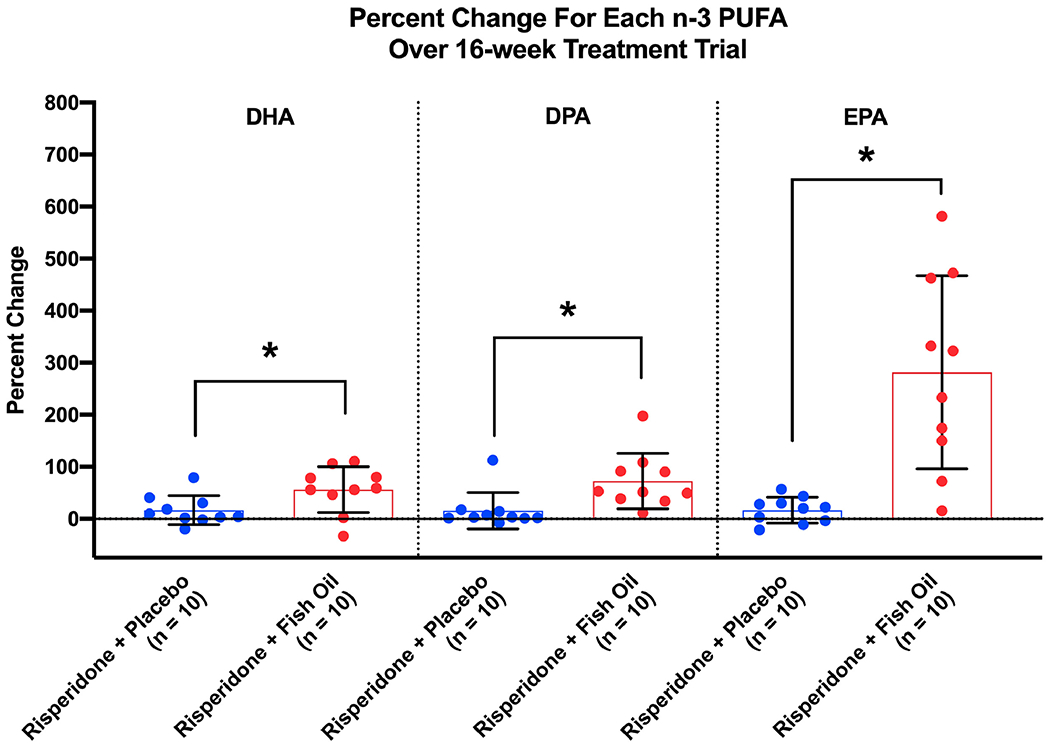

There was a significant (F = 21.02, df = 1, p < 0.001) group x time interaction indicating that individuals treated with risperidone + FO demonstrated a greater overall increase in n-3 PUFAs compared to individuals treated with risperidone + placebo. DPA (t = −6.99, df = 9, p < 0.001; +72.6%), DHA (t = −4.48, df = 9, p = 0.002; +56.2%) and EPA (t = −4.91, df = 9, p = 0.001; +281.7%) increased significantly in the risperidone + FO group, but not in the risperidone + placebo group (p’s > 0.05) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percent Change of Each n-3 PUFA over the 16-week Treatment Trial.

3.4. Relationship between n-3 PUFAs and Diffusion Measures

At baseline, DHA and DPA were significantly and positively correlated with FA (n = 37, pFWE < 0.05; see Figure 2). Significant correlations with FA were localized to the right retrolenticular part of the internal capsule and the right posterior corona radiata for both DHA and DPA (see Figure 2) representing 0.2% and 1.05% of the skeleton, respectively. Further, applying Free Water Imaging, we found significant positive correlations of DHA and DPA with FA-t. These correlations encompassed a greater proportion of the skeleton (DHA: 3.05%; DPA: 10.4%) extending to additional areas such as the splenium (DPA), right superior corona radiata (DPA and DHA), right anterior corona radiata (DPA), right posterior limb of the internal capsule (DPA and DHA) and bilateral superior longitudinal fasciculi (DPA) (see Figure 2). There were no significant correlations between erythrocyte n-3 PUFA levels and FW. In addition, EPA was not significantly correlated with any of the diffusion measures.

Figure 2.

Illustration of Baseline (N=37) Correlations of Fractional Anisotropy (FA, Panels A and B), Free Water (FW, Panels C and D) and Fractional Anisotropy of the Tissue (FA-t, Panels E and F) with Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA, left) and Docosapentaenoic Acid (DPA, right). All images are presented in radiologic convention.

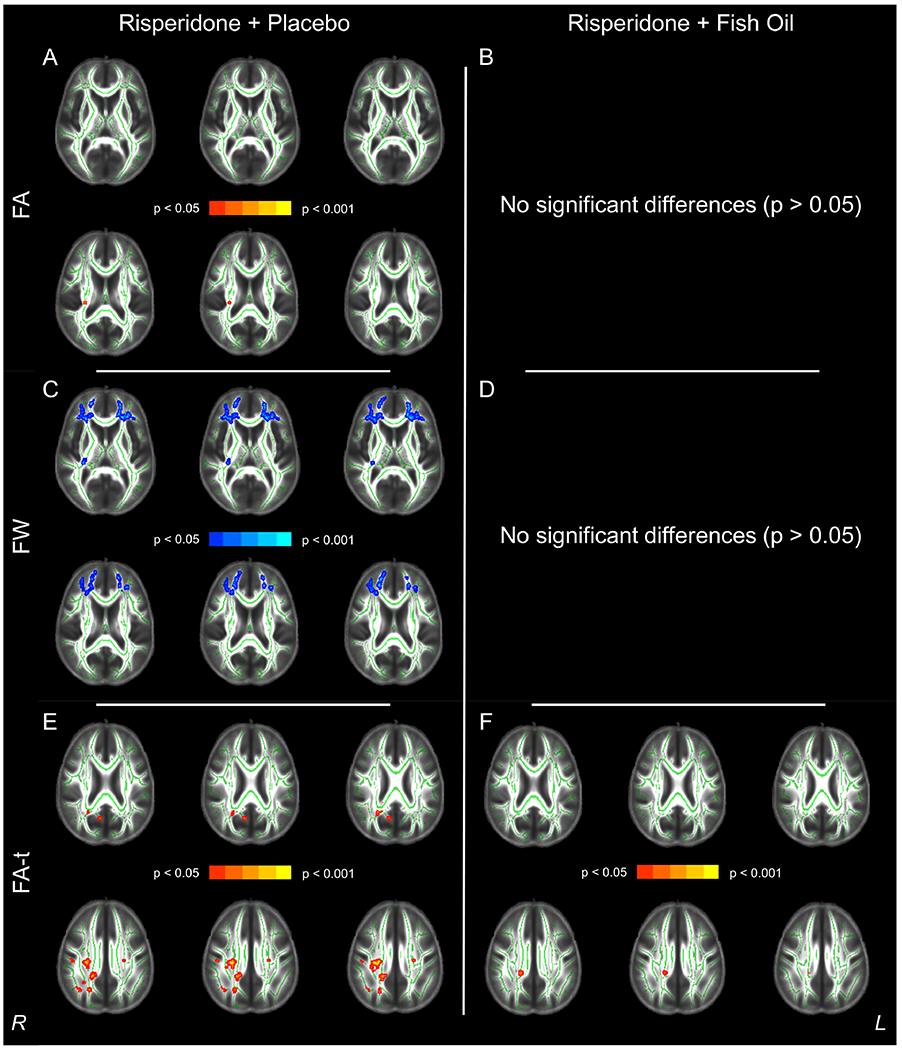

There were no treatment group differences at baseline or follow-up regarding FA, or the Free Water Imaging measures FA-t and FW. Further, independent groups t-tests on the difference maps were not significant for the diffusion measures. When assessing within-group differences, individuals who received risperidone + placebo demonstrated significant reductions in FA at the time of their follow-up scan (n = 8, pFWE < 0.05) in the right posterior limb and right retrolenticular part of the internal capsule as well as the right posterior corona radiata affecting 0.31% of the entire skeleton. Free Water Imaging revealed reductions in FA-t mainly in the splenium, right posterior and superior corona radiata (affecting 3.05% of the entire skeleton), as well as robust increases in FW (affecting 17.53% of the skeleton) that were most evident within the frontal lobes (see Figure 3). In contrast, individuals receiving risperidone + FO demonstrated no significant changes in FA or FW and a much more limited reduction (0.27% of the skeleton affected; n = 10, pFWE < 0.05; Figure 3) in FA-t compared to the change in FA-t observed in the risperidone + placebo group.

Figure 3.

Summary of Within-Subjects Analysis Findings for Reductions in Fractional Anisotropy (FA, Red, Panels A and B), Increases in Free Water (FW, Blue, Panels C and D) and Reductions in Fractional Anisotropy of the Tissue (FA-t, Red, Panels E and F) over the Course of the Treatment Trial in the Risperidone + Placebo Group (Left Column) versus the Risperidone + Fish Oil Group (Right Column). All images are presented in radiologic convention.

4. Discussion

We collected dMRI scans in the context of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of adjuvant FO to risperidone treatment in patients with recent-onset psychosis. Prior to treatment, there were robust positive correlations of FA-t with DHA and DPA in patients, suggesting that erythrocyte n-3 PUFA levels are associated with white matter microstructural properties that may reflect axonal or myelination health. Patients receiving risperidone + placebo demonstrated significant reductions in FA and FA-t and increases in FW that were either absent (i.e., FA and FW) or largely attenuated (i.e., FA-t) in patients treated with risperidone + FO. These longitudinal findings provide preliminary evidence that concomitant administration of n-3 PUFAs may mitigate changes in white matter microstructural measures observed in recent-onset psychosis patients treated with risperidone.

Our findings are consistent with studies implicating a potential role for PUFA biosynthesis in compromised white matter previously observed in psychosis patients (Peters et al., 2013a; 2009a). In the present study, the positive correlations between n-3 PUFA levels at baseline, specifically DHA and DPA, and the traditional DTI metric, FA, replicate prior work (Peters et al., 2013a; 2009c). The observation that EPA did not correlate with DTI measures is consistent with previous studies (Chhetry et al., 2016 Tam et al., 2016), and may be due to the rapid beta-oxidization of EPA following entry into the brain (Chen et al., 2009). Our study extends this work, however, through the use of a diffusion metric that is more specific to tissue-related processes (i.e., FA-t), which may better reflect the health or maintenance of myelin. Indeed, the spatial extent of the positive correlations between FA-t with DPA and DHA encompass a much greater proportion of the white matter skeleton compared to FA.

Our findings support the hypothesis that adjuvant FO may attenuate white matter abnormalities in patients with early-phase psychosis treated with risperidone. Specifically, the lack of FW elevations coupled with the diminished FA-t reduction in patients treated with risperidone + FO is consistent with the hypothesis that the administration of n-3 PUFAs may limit white matter deterioration and/or dampen pro-inflammatory responses in the brain. While the laterality (FA/FA-t) and focal nature (FW) of our longitudinal findings might suggest either regionally specific effects due to intrinsic disease processes or treatment with risperidone and/or FO, it is more plausible that they are attributable to limited power due to our relatively small sample size.

Recent dMRI studies utilizing Free Water Imaging indicate that patients in the early stages of illness exhibit global elevations in extracellular FW, which has been proposed to be a potential proxy for acute activated immune states in the brain (Di Biase et al., 2019; Lyall et al., 2018; Pasternak et al., 2012). White matter, in particular, has been shown to become vulnerable in chronic inflammatory states (Bennet et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2015). This should be interpreted with caution, however, because the FW metric has not yet been validated as a neuroimaging biomarker of neuroinflammation.

Pathological processes responsible for abnormal white matter observed early in psychosis remain unclear. Although antipsychotic medication exposure may be associated with white matter volume reductions in patients with psychosis (Ho et al., 2011) and a loss of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in animal studies (Dorph-Petersen et al., 2005; Konopaske et al., 2008), other studies suggest that atypical antipsychotics may protect white matter by promoting myelination (Steiner et al., 2014; L. Xiao et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2012) and normalizing elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (McNamara et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2011). Results from DTI studies have also provided conflicting results, with evidence for FA reductions (Meng et al., 2019; Szeszko et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013), increases (Ebdrup et al., 2016; Reis Marques et al., 2014) or no changes (Kraguljac et al., 2019) following antipsychotic treatment. Discrepant neuroimaging findings may be related to methodological differences, although the use of more specific diffusion metrics described in this study may be useful for understanding the impact of antipsychotic treatment, as well as FO, on white matter.

There are several study limitations, that should be acknowledged. Without a healthy comparison group we could not determine whether patients had lower n-3 PUFA levels or abnormal white matter at baseline, although both have been reported previously by our group and others (e.g., (Kelly et al., 2017; Reddy et al., 2004; van der Kemp et al., 2012)). The sample size for the longitudinal imaging comparisons was small, although our findings did survive correction for Type-I error. The lack of significant cross-sectional differences at follow-up suggests that larger samples are needed to corroborate the potential beneficial treatment effects of FO supplementation. Similarly, the lack of females at follow-up in the risperidone + placebo cohort limits our ability to interrogate the possible role of sex. We also acknowledge that white matter may change in association with illness progression independent of antipsychotic treatment (Kelly et al., 2017; Y. Xiao et al., 2018). We could not disentangle the independent contribution of possible antipsychotic-induced white matter changes vs. illness progression, although these findings nevertheless suggest that FO supplementation may at least partly mitigate against white matter changes in patients with recent-onset psychosis treated with risperidone.

5. Conclusion

Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that treatment with FO as an adjuvant therapy to risperidone may be associated with myelin changes in individuals with recent-onset psychosis treated with risperidone. Moreover, we show that the application of advanced dMRI methods, such as Free Water Imaging, can provide novel information regarding the microstructural correlates of FO supplementation not otherwise available using traditional dMRI methods.

Highlights.

n-3 PUFAs are associated with white matter properties in psychosis

n-3 PUFAs may attenuate white matter changes in patients treated with risperidone

Free Water Imaging provides new information regarding these biological mechanisms

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge funding provided by the following National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: R21 MH101746 (PIs: Delbert G. Robinson/Philip R. Szeszko); R03 MH110745, K01 MH115247-01A1 (PI: Amanda E. Lyall); K23 MH100264 (PI: Juan A. Gallego); R01 MH102377, K24 MH110807 (PI: Marek Kubicki); R01 MH108574 (PI: Ofer Pasternak); R01 DK097599 (PI: Robert K. McNamara); as well as the Claussen-Simon-Stiftung: Dissertation Plus (PI: Felix L. Nägele); the Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program (PI: Anil K. Malhotra); and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (PI: Bart D. Peters). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

This work was prepared in the context of Felix L. Nägele’s doctoral dissertation at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany. These data were presented by Philip R. Szeszko at the annual meeting for the Society of Biological Psychiatry in 2018 and by Amanda E. Lyall at the annual meeting for the Schizophrenia International Research Society in 2019.

Conflict of Interest Statements

Amanda E. Lyall, Felix L. Nägele, Ofer Pasternak, Juan A. Gallego, Robert K. McNamara, Marek Kubicki, Bart D. Peters and Philip R. Szeszko have no relevant financial disclosures. Anil K. Malhotra has served as a consultant for Forum Pharmaceuticals and has served on a scientific advisory board for Genomind. Delbert G. Robinson has been a consultant to Costello Medical Consulting, Innovative Science Solutions, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and US WorldMeds and has received research support from Otsuka.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bennet L, Dhillon S, Lear CA, van den Heuij L, King V, Dean JM, Wassink G, Davidson JO, Gunn AJ, 2018. Chronic inflammation and impaired development of the preterm brain. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 125, 45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenhead K, Addington J, Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, Mathalon D, McGlashan T, Perkins D, Seidman LJ, Tsuang M, Walker E, Woods SW, 2017. Omega-3 fatty acid versus placebo in a clinical high-risk sample from the north american prodrome longitudinal studies (NAPLS) consortium. Schizophrenia Bulletin 43, S16–S16. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx021.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AT, Chibnall JT, Nasrallah HA, 2015. A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials of omega-3 fatty acid augmentation in schizophrenia: Possible stage-specific effects. Ann Clin Psychiatry 27, 289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew L-J, Fusar Poli P, Schmitz T, 2013. Oligodendroglial alterations and the role of microglia in white matter injury: relevance to schizophrenia. Dev Neurosci 35, 102–129. doi: 10.1159/000346157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CT, Liu Z, Ouellet M, Calon F, Bazinet RP, 2009. Rapid beta-oxidation of eicosapentaenoic acid in mouse brain: an in situ study. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids 80, 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhetry BT, Hezghia A, Miller JM, Lee S, Rubin-Falcone H, Cooper TB, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ, Sublette ME., 2016. Omeqa-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation and white matter changes in major depression. J Psvchiatr Res 75, 65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Ambinder EB, Ward RE, Minn I, Vranesic M, Kim PK, Ford CN, Higgs C, Hayes LN, Schretlen DJ, Dannals RF, Kassiou M, Sawa A, Pomper MG, 2016. In vivo markers of inflammatory response in recent-onset schizophrenia: a combined study using |[lsqb]|11C|[rsqb]|DPA-713 PET and analysis of CSF and plasma. Transl Psychiatry 6, e777. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Biase MA, Katabi G, Piontkewitz Y, Cetin Karayumak S, Weiner I, Pasternak O, 2019. Increased extracellular free-water in adult male rats following in utero exposure to maternal immune activation. Brain Behav. Immun. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorph-Petersen KA, Pierri JN, Perel JM, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Lewis DA, 2005. The influence of chronic exposure to antipsychotic medications on brain size before and after tissue fixation: a comparison of haloperidol and olanzapine in macaque monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 30, 1649–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebdrup BH, Raghava JM, Nielsen MØ, Rostrup E, Glenthøj B, 2016. Frontal fasciculi and psychotic symptoms in antipsychotic-naive patients with schizophrenia before and after 6 weeks of selective dopamine D2/3 receptor blockade. J Psychiatry Neurosci 41, 133–141. doi: 10.1503/jpn.150030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillman SG, Cloonan N, Catts VS, Miller LC, Wong J, McCrossin T, Cairns M, Weickert CS, 2013. Increased inflammatory markers identified in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry 18, 206–214. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, 1996. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders— Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). [Google Scholar]

- Hakak Y, Walker JR, Li C, Wong WH, Davis KL, Buxbaum JD, Haroutunian V, Fienberg AA, 2001. Genome-wide expression analysis reveals dysregulation of myelination-related genes in chronic schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 98, 4746–4751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081071198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho B-C, Andreasen NC, Ziebell S, Pierson R, Magnotta V, 2011. Long-term antipsychotic treatment and brain volumes: a longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 128–137. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrobin DF, 1998. The membrane phospholipid hypothesis as a biochemical basis for the neurodevelopmental concept of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 30, 193–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S, Jahanshad N, Zalesky A, Kochunov P, Agartz I, Alloza C, Andreassen OA, Arango C, Banaj N, Bouix S, Bousman CA, Brouwer RM, Bruggemann J, Bustillo J, Cahn W, Calhoun V, Cannon D, Carr V, Catts S, Chen J, Chen J-X, Chen X, Chiapponi C, Cho KK, Ciullo V, Corvin AS, Crespo-Facorro B, Cropley V, De Rossi P, Diaz-Caneja CM, Dickie EW, Ehrlich S, Fan F-M, Faskowitz J, Fatouros-Bergman H, Flyckt L, Ford JM, Fouche J-P, Fukunaga M, Gill M, Glahn DC, Gollub R, Goudzwaard ED, Guo H, Gur RE, Gur RC, Gurholt TP, Hashimoto R, Hatton SN, Henskens FA, Hibar DP, Hickie IB, Hong LE, Horacek J, Howells FM, Hulshoff Pol HE, Hyde CL, Isaev D, Jablensky A, Jansen PR, Janssen J, Jönsson EG, Jung LA, Kahn RS, Kikinis Z, Liu K, Klauser P, Knöchel C, Kubicki M, Lagopoulos J, Langen C, Lawrie S, Lenroot RK, Lim KO, Lopez-Jaramillo C, Lyall A, Magnotta V, Mandl RCW, Mathalon DH, McCarley RW, McCarthy-Jones S, McDonald C, McEwen S, McIntosh A, Melicher T, Mesholam-Gately RI, Michie PT, Mowry B, Mueller BA, Newell DT, O’Donnell P, Oertel-Knöchel V, Oestreich L, Paciga SA, Pantelis C, Pasternak O, Pearlson G, Pellicano GR, Pereira A, Pineda Zapata J, Piras F, Potkin SG, Preda A, Rasser PE, Roalf DR, Roiz R, Roos A, Rotenberg D, Satterthwaite TD, Savadjiev P, Schall U, Scott RJ, Seal ML, Seidman LJ, Shannon Weickert C, Whelan CD, Shenton ME, Kwon JS, Spalletta G, Spaniel F, Sprooten E, Stäblein M, Stein DJ, Sundram S, Tan Y, Tan S, Tang S, Temmingh HS, Westlye LT, Tønnesen S, Tordesillas-Gutierrez D, Doan NT, Vaidya J, van Haren NEM, Vargas CD, Vecchio D, Velakoulis D, Voineskos A, Voyvodic JQ, Wang Z, Wan P, Wei D, Weickert TW, Whalley H, White T, Whitford TJ, Wojcik JD, Xiang H, Xie Z, Yamamori H, Yang F, Yao N, Zhang G, Zhao J, van Erp TGM, Turner J, Thompson PM, Donohoe G, 2017. Widespread white matter microstructural differences in schizophrenia across 4322 individuals: results from the ENIGMA Schizophrenia DTI Working Group. Molecular Psychiatry 1, 66. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopaske GT, Dorph-Petersen K-A, Sweet RA, Pierri JN, Zhang W, Sampson AR, Lewis DA, 2008. Effect of chronic antipsychotic exposure on astrocyte and oligodendrocyte numbers in macaque monkeys. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraguljac NV, Anthony T, Skidmore FM, Marstrander J, Morgan CJ, Reid MA, White DM, Jindal RD, Melas Skefos NH, Lahti AC, 2019. Micro- and Macrostructural White Matter Integrity in Never-treated and Currently Unmedicated Patients with Schizophrenia and Effects of Short Term Antipsychotic Treatment. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling J, Merideth F, Caprihan A, Pena A, Teshiba T, Mayer AR, 2012. Head injury or head motion? Assessment and quantification of motion artifacts in diffusion tensor imaging studies. Hum. Brain Mapp. 33, 50–62. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JJ, Green P, John Mann J, Rapoport SI, Sublette ME, 2015. Pathways of polyunsaturated fatty acid utilization: Implications for brain function in neuropsychiatric health and disease. Brain Research 1597, 220–246. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.11.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyall AE, Pasternak O, Robinson DG, Newell D, Trampush JW, Gallego JA, Fava M, Malhotra AK, Karlsgodt KH, Kubicki M, Szeszko PR, 2018. Greater extracellular free-water in first-episode psychosis predicts better neurocognitive functioning. Molecular Psychiatry 23, 701–707. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara RK, Asch RH, Lindquist DM, Krikorian R, 2017. Role of polyunsaturated fatty acids in human brain structure and function across the lifespan: An update on neuroimaging findings. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids, doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara RK, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, 2011. Chronic risperidone normalizes elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine and C-reactive protein production in omega-3 fatty acid deficient rats. European Journal of Pharmacology 652, 152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara RK, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, Dwivedi Y, Pandey GN, 2013. Adult medication-free schizophrenic patients exhibit long-chain omega-3 Fatty Acid deficiency: implications for cardiovascular disease risk. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2013, 796462–10. doi: 10.1155/2013/796462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Li K, Li W, Xiao Y, Lui S, Sweeney JA, Gong Q, 2019. Widespread white-matter microstructure integrity reduction in first-episode schizophrenia patients after acute antipsychotic treatment. Schizophrenia Research 204, 238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, Mellor A, Kirkpatrick B, 2011. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najjar S, Pearlman DM, 2015. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophrenia Research 161, 102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nortje G, Stein DJ, Radua J, Mataix-Cols D, Horn N, 2013. Systematic review and voxel-based meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging studies in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 150, 192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton I, Essayed WI, Zhang F, Pujol S, Yarmarkovich A, Golby AJ, Kindlmann G, Wassermann D, Estepar RSJ, Rathi Y, Pieper S, Kikinis R, Johnson HJ, Westin C-F, O’Donnell LJ, 2017. SlicerDMRI: Open Source Diffusion MRI Software for Brain Cancer Research. Cancer Res. 77, e101–e103. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozgen H, Baron W, Hoekstra D, Kahya N, 2016. Oligodendroglial membrane dynamics in relation to myelin biogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 3291–3310. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2228-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Kelly S, Sydnor VJ, Shenton ME, 2018. Advances in microstructural diffusion neuroimaging for psychiatric disorders. Neuroimage 182, 259–282. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.04.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Sochen N, Gur Y, Intrator N, Assaf Y, 2009. Free water elimination and mapping from diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med 62, 717–730. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Westin C-F, Bouix S, Seidman LJ, Goldstein JM, Woo T-UW, Petryshen TL, Mesholam-Gately RI, McCarley RW, Kikinis R, Shenton ME, Kubicki M, 2012. Excessive extracellular volume reveals a neurodegenerative pattern in schizophrenia onset. Journal of Neuroscience 32, 17365–17372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2904-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DO, Jeffries CD, Addington J, Bearden CE, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt BA, Mathalon DH, McGlashan TH, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R, 2014. Towards a Psychosis Risk Blood Diagnostic for Persons Experiencing High-Risk Symptoms: Preliminary Results From the NAPLS Project. Schizophrenia Bulletin 41, 419–428. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters BD, Duran M, Vlieger EJ, Majoie CB, Heeten, den GJ, Linszen DH, de Haan L., 2009a. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and brain white matter anisotropy in recent-onset schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 81, 61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters BD, Duran M, Vlieger EJ, Majoie CB, Heeten, den GJ, Linszen DH, de Haan L., 2009b. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and brain white matter anisotropy in recent-onset schizophrenia: A preliminary study. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 81, 61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters BD, Duran M, Vlieger EJ, Majoie CB, Heeten, den GJ, Linszen DH, de Haan L, 2009c. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and brain white matter anisotropy in recent-onset schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 81, 61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters BD, Machielsen MWJ, Hoen WP, Caan MWA, Malhotra AK, Szeszko PR, Duran M, Olabarriaga SD, de Haan L, 2013a. Polyunsaturated fatty acid concentration predicts myelin integrity in early-phase psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 39, 830–838. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters BD, Machielsen MWJ, Hoen WP, Caan MWA, Malhotra AK, Szeszko PR, Duran M, Olabarriaga SD, de Haan L, 2013b. Polyunsaturated fatty acid concentration predicts myelin integrity in early-phase psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 39, 830–838. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad KM, Upton CH, Nimgaonkar VL, Keshavan MS, 2015. Differential susceptibility of white matter tracts to inflammatory mediators in schizophrenia: An integrated DTI study. Schizophrenia Research 161, 119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.09.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy RD, Keshavan MS, Yao JK, 2004. Reduced red blood cell membrane essential polyunsaturated fatty acids in first episode schizophrenia at neuroleptic-naive baseline. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30, 901–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis Marques T, Taylor H, Chaddock C, Dell’Acqua F, Handley R, Reinders AATS, Mondelli V, Bonaccorso S, DiForti M, Simmons A, David AS, Murray RM, Pariante CM, Kapur S, Dazzan P, 2014. White matter integrity as a predictor of response to treatment in first episode psychosis. Brain 137, 172–182. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DG, Gallego JA, John M, Hanna LA, Zhang J-P, Birnbaum ML, Greenberg J, Naraine M, Peters BD, McNamara RK, Malhotra AK, Szeszko PR, 2019. A potential role for adjunctive omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for depression and anxiety symptoms in recent onset psychosis: Results from a 16 week randomized placebo-controlled trial for participants concurrently treated with risperidone. Schizophrenia Research 204, 295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal D, Koschnick JR, Siegers LHA, Hof PR, 2007. Oligodendrocyte pathophysiology: a new view of schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 10, 503–511. doi: 10.1017/S146114570600722X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z, Ren H, Luo C, Yao X, Li P, He C, Kang J-X, Wan J-B, Yuan T-F, Su H, 2016. Enriched Endogenous Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Protect Cortical Neurons from Experimental Ischemic Injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 53, 6482–6488. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9554-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, Watkins KE, Ciccarelli O, Cader MZ, Matthews PM, Behrens TEJ, 2006. Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 31, 1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Nichols TE, 2009. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 44, 83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner J, Martins-de-Souza D, Schiltz K, Sarnyai Z, Westphal S, Isermann B, Dobrowolny H, Turck CW, Bogerts B, Bernstein H-G, Horvath TL, Schild L, Keilhoff G, 2014. Clozapine promotes glycolysis and myelin lipid synthesis in cultured oligodendrocytes. Front Cell Neurosci 8, 384. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeszko PR, Robinson DG, Ikuta T, Peters BD, Gallego JA, Kane J, Malhotra AK, 2014. White matter changes associated with antipsychotic treatment in first-episode psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 1324–1331. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam EW, Chau V, Barkovich AJ, Ferriero DM, Miller SP, Rogers EE, Grunau RE, Synnes AR, Xu D, Foong J, Brant R, Innis SM, 2016. Early postnatal docosahexaenoic acid levels and improved preterm brain development. Pediatr Res 79, 723–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachev D, Mimmack ML, Ryan MM, Wayland M, Freeman T, Jones PB, Starkey M, Webster MJ, Yolken RH, Bahn S, 2003. Oligodendrocyte dysfunction in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The Lancet 362, 798–805. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14289-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trépanier MO, Hopperton KE, Mizrahi R, Mechawar N, Bazinet RP, 2016. Postmortem evidence of cerebral inflammation in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Molecular Psychiatry 21, 1009–1026. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uranova NA, Vostrikov VM, Vikhreva OV, Zimina IS, Kolomeets NS, Orlovskaya DD, 2007. The role of oligodendrocyte pathology in schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 10, 537–545. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707007626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kemp WJM, Klomp DWJ, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff Pol HE, 2012. A meta-analysis of the polyunsaturated fatty acid composition of erythrocyte membranes in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 141, 153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kesteren CFMG, Gremmels H, de Witte LD, Hoi EM, Van Gool AR, Falkai PG, Kahn RS, Sommer IEC, 2017. Immune involvement in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis on postmortem brain studies. Transl Psychiatry 7, e1075. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Cheung C, Deng W, Li M, Huang C, Ma X, Wang Y, Jiang L, Sham PC, Collier DA, Gong Q, Chua SE, McAlonan GM, Li T, 2013. White-matter microstructure in previously drug-naive patients with schizophrenia after 6 weeks of treatment. Psychol Med 43, 2301–2309. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AL, Voineskos AN, 2014. A review of structural neuroimaging in schizophrenia: from connectivity to connectomics. Front Hum Neurosci 8, 653. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Webster MA, Smith SM, Nichols TE, 2014. Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage 92, 381–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte AV, Kerti L, Hermannstädter HM, Fiebach JB, Schreiber SJ, Schuchardt JP, Hahn A, Floöel A, 2014. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids improve brain function and structure in older adults. Cereb. Cortex 24, 3059–3068. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woerner MG, Mannuzza S, Kane JM, 1988. Anchoring the BPRS: an aid to improved reliability. Psychopharmacol Bull 24, 112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Xu H, Zhang Y, Wei Z, He J, Jiang W, Li X, Dyck LE, Devon RM, Deng Y, Li XM, 2008. Quetiapine facilitates oligodendrocyte development and prevents mice from myelin breakdown and behavioral changes. Molecular Psychiatry 13, 697–708. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Sun H, Shi S, Jiang D, Tao B, Zhao Y, Zhang W, Gong Q, Sweeney JA, Lui S, 2018. White Matter Abnormalities in Never-Treated Patients With Long-Term Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 175, 1129–1136. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17121402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Gao Z, Zhang H, Fang Z, Wu C, Xu H, Huang Q-J, 2015. Changes in proinflammatory cytokines and white matter in chronically stressed rats. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 11, 597–607. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S78131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zendedel A, Habib P, Dang J, Lammerding L, Hoffmann S, Beyer C, Slowik A, 2015. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids ameliorate neuroinflammation and mitigate ischemic stroke damage through interactions with astrocytes and microglia. J. Neuroimmunol. 278, 200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang H, Wang L, Jiang W, Xu H, Xiao L, Bi X, Wang J, Zhu S, Zhang R, He J, Tan Q, Zhang D, Kong J, Li X-M, 2012. Quetiapine enhances oligodendrocyte regeneration and myelin repair after cuprizone-induced demyelination. Schizophrenia Research 138, 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]