Abstract

Background

Equitable health financing is crucial to attaining universal health coverage (UHC). Health financing, a major focus of the National Health Insurance in South Africa, can potentially affect income distribution.

Objective

This paper assesses the impact of financing health services on income inequality (i.e. the income redistributive effect [RE]) in South Africa.

Methods

Data come from the nationally representative Income and Expenditure Survey (2010/2011). A standard approach is used to estimate and decompose RE for the major health financing mechanisms (taxes, insurance and out-of-pocket health spending) into the sum of the vertical effect (i.e. the extent of progressivity or regressivity), horizontal inequity (i.e. the extent to which ‘equals’ are not treated equally) and reranking effect (i.e. the extent to which individuals or households change ranks after paying for health services).

Results

Financing health services through direct taxes (RE = 0.0072, P < 0.01) and private health insurance (RE = 0.0103, P < 0.01) significantly reduce income inequality, while indirect taxes (RE = −0.0025, P < 0.01) and out-of-pocket health spending (RE = −0.0009, P < 0.01) lead to significant increases in income inequality. Although private health insurance contributions may reduce income inequality, enrolees are only a small minority, mainly the rich. Also, total taxes (RE = 0.0048, P < 0.01) and total health financing (RE = 0.0152, P < 0.01) contribute to significant reductions in income inequality, with the vertical effect dominating.

Conclusion

Taxes that contribute to reducing income inequality hold promise for equitable health financing in South Africa. The results are relevant for and support the current National Health Insurance policy in South Africa and the global move towards UHC.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| The high income inequality in South Africa can be reduced by health financing reform. |

| Direct taxes and private health insurance reduce income inequality in South Africa. |

| Income redistribution via private health insurance is limited as only the rich insure. |

| Indirect taxes and out-of-pocket health spending increase income inequality in South Africa. |

| Progressive general taxes are useful for reducing income inequality in South Africa. |

Introduction

Equitable health financing is central to the universal health coverage (UHC) debate. UHC is about ensuring that all people have access to needed health services that are of sufficient quality to be effective, without incurring any financial hardship as a result of the use or the need to use these services [1–3]. Health financing is equitable when contributions to health services are based on households’ ability to pay [4]. Apart from affecting equity in how health services are financed, financing health services also affects income inequality because these services are financed (whether through taxes, insurance premiums or out-of-pocket payments) from household income. In many countries in Africa, government taxes form a substantial share of health financing. Another large share is direct out-of-pocket payments [5]. Health financing via indirect taxes is likely to be more regressive than direct taxes because direct taxes are structured with progressive rates in most cases. Indirect taxes, especially in developed as opposed to developing economies, are more likely to be regressive because their rates are not very sensitive to the distribution of income, even when some commodities and services are exempted or zero-rated [5, 6].

In South Africa, health services are financed through a combination of taxes (direct and indirect), private health insurance contributions (called medical schemes) and direct out-of-pocket payments, with taxes accounting for less than half of the total health financing. In 2010/2011, tax revenue accounted for over 98% of South Africa’s national revenue. Tax on income and profits constituted over 56% of total tax revenue, while value-added tax, fuel levy and excise tax accounted for 27.2%, 5.1% and 3.6% of total tax revenue, respectively [7]. Together, these taxes account for over 92% of tax revenue. Other components include taxes on international trade and transactions, including customs duties (4.0%), taxes on payroll and workforce (1.3%) and taxes on property (1.4%). Overall, direct and indirect taxes account for about 59% and 41% of total tax revenue, respectively. This ratio of direct and indirect taxes in total tax revenue has remained very similar over the past decade. The contributions of the various tax components to health financing are provided in the data section below. The country has both the public and private health sectors, serving different socioeconomic groups—the public sector serves the majority of the population and is funded mainly through allocations from general tax revenue [8, 9], while the private sector serves a minority of the population, primarily those who can afford private health insurance.

South Africa remains one of the most unequal societies in the world, with a Gini index of income inequality that is close to 0.70 [10]. The Gini index of income inequality declined marginally from 0.68 in 1993 (i.e. shortly before transition to a democratic government in 1994) to 0.66 in 2014/2015 [10]. Labour income (~ 90%) followed by investment income (~ 9%) is the major contributor to income inequality in South Africa [10]. Although inequality in earnings has decreased since 1994, the gaps in earning between race groups are still high “with black Africans (comprising more than 75% of the population) on average earning less than half of what whites earn” ([11], p.6; emphasis added based on census data). The labour market, which is the primary target for income taxes, is therefore a major driver of income inequality in South Africa. Therefore, efforts to reduce income inequality in South Africa cannot ignore labour and investment incomes. The country’s National Development Plan’s target is to reduce the Gini index to 0.6 by 2030 [12], coinciding with the Sustainable Development Goals end date. Given the importance of the labour market for income inequality, if the country’s health financing system, to be financed predominantly through taxes, is very well designed, among other things, it may contribute to substantial reductions in the level of income inequality in South Africa to meet the projected target for reduction in income inequality.

There is no doubt that health financing, whether through taxes, health insurance contributions or out-of-pocket spending, involves some intra- and inter-household decisions that may impact the distribution and redistribution of income within and between households. Although the primary purpose of health financing is not to redistribute income [13], the extent to which income distribution is affected by health financing remains an important policy issue. It is determined by the way individuals and households end up being treated by the health financing system. When the system is financed using progressive mechanisms to impose a lesser financial burden on the poor relative to the rich, it usually redistributes income away from the rich to the poor, leading to reductions in income inequality. Minimising differential treatments in the form of horizontal inequity and reranking households also improve the extent of income redistribution associated with health financing. Different countries have different health financing mixes. Some countries such as Denmark, Ireland, Niue, Swaziland, Sweden, Thailand and the United Kingdom, for example, rely more on taxes, while many developing countries such as Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sierra Leone and Zambia rely heavily on direct out-of-pocket health spending [14]. The relative progressivity and shares of these mechanisms in overall health financing to a large extent determine the degree to which health financing can redistribute income. This does not necessarily depend on whether the country is developed or is still developing. In fact, in some developed countries such as Denmark, the United States, Switzerland, Portugal, Germany and the Netherlands, overall health financing increased income inequality [15–17]. This unfavourable increase in income inequality associated with financing health services translates into a negative redistribution of income away from the poor to the rich.

While there are competing methodologies to assess the extent of income redistribution associated with some tax regimes or health financing systems, their application to studying health financing is limited. It is only a few studies, mainly within developed countries, that have provided empirical evidence on the extent to which health financing could lead to differential treatment of individuals and households [15, 16, 18]. The dearth of studies that examine the impact of health financing on income inequality in developing countries is often attributed to data insufficiency. However, reliable data are becoming increasingly available to researchers to provide evidence in developing countries where poverty, unemployment, inequality and disease are endemic. It is debated that for the assessment of fairness in health financing, including the redistributive effect (RE), researchers should go beyond focusing solely on ‘ability to pay’ and investigate a broader well-being concept that includes receiving health care [19]. While this paper acknowledges the importance of an integrated analysis, it focuses on the ability-to-pay principle, an important consideration in assessing a health system’s performance towards achieving UHC [20].

This paper presents a detailed empirical assessment of the income RE of South Africa’s health financing system. In other words, the paper assesses the impact of health financing (taxes, insurance and out-of-pocket payments) on income distribution or income inequality in South Africa. It seeks to uncover the extent to which the country achieves substantial income inequality reductions through financing health services.

Materials and methods

Data

Data come from the 2010/2011 Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) nationally representative Income and Expenditure Survey (IES) conducted between September 2010 and August 2011. The sampling involved selecting 3254 primary sampling units (PSU) and a total of 27,665 households, with an 83% response rate. The IES data were collected using a combination of the diary and questionnaire recall methods [21]. Three broad categories of health financing mechanisms are considered in this paper—taxes, private health insurance and direct out-of-pocket health spending [22]. Each household’s total payments or contributions are estimated for each of the broad health financing mechanisms, as suggested in Ataguba et al. [4]. Table 1 contains details for extracting the variables used in this paper. Only the proportion of tax revenue allocated to the health sector (11.9% in 2011) is accounted for in analysing taxes for health financing. It is essential to highlight that the relative shares of the various components to health financing in South Africa have remained relatively similar over the last decade [14].

Table 1.

Extracting the various health financing mechanisms from survey data

| Component (1) | Share in total health financing (%) (2) | Ratesa (3) | Incidence assumption | Computation technique (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxes | 38.2 | |||

| Direct taxes (using personal income tax as a proxy) | 21.5 |

18–40% depending on income level plus flat rate contribution as a function of income 0% tax for incomes below R57,000 for individuals below 65 years and R88,528 for individuals 65 years or older A rebate of R10,260 and R5675 for individuals below 65 years and 65 years or older, respectively |

Legal tax payer/household | Apply the appropriate tax thresholds, tax rate and rebates to the gross income of individuals within each household within the taxable range |

| Value-added tax (VAT) | 10.4 | 14% on standard rated goods and services | Consumers (individuals/households) | The VAT rate is applied to expenditure on goods and services that are standard rated, i.e. excluding the zero-rated and exempted goods |

| Fuel levy | 2 | R1.68/litre for petrol and R1.53/litre for diesel | Consumers (individuals/households) | Since fuel is consumed by households (personal or public transportation) as well as corporate or industrial users, estimation involved a process of generating the component attributable for public transport users, personal transport users and users in businesses. We assumed that the fuel levy is shifted to consumers reporting expenditure on minibus taxis, buses and other types of public transport. Fuel tax accruing to businesses and corporate users is also assumed to be passed forward onto consumers. Because we could not directly estimate the component attributed to corporate or industrial users from the dataset, we assumed that the difference between the fuel levy components accounted for by private and public transport users and that reported by the National Treasury is attributable to industrial users |

| Excise tax | 1.4 |

52% of retail price for cigarettes R2.50/litre for beer R0.08/litre of traditional beer R2.14-R6.67/litre of wine R33.83/litre of spiritsb |

Consumers (individuals/households) | For cigarettes, the tax rate is applied to the expenditure on cigarette products. For beer, wine and spirits, the reported expenditure on these products is translated into estimated quantities (litres) using average retail prices; the rate per litre was then applied |

| Others | 2.9 | Includes taxes on property and unidentified levies, stamp duties and fines, air departure tax and skills development levy | – | Not estimated. This is assumed to be distributed as total indirect taxes |

| Health insurance | 49.9 | |||

| Medical schemes (private) | 49.9 | – | Insured individual/householdc | Expenditure on medical scheme premiums by households is combined with employers’ contributions on behalf of members of the household |

| Out-of-pocket (OOP) payment | 12 | |||

| OOP payments | 12 | – | Health service user (individuals/households) | Household expenditure on medicines, consultations, treatments and procedures are summed |

Source: [60]

R South African rand

aThis applies to the taxes in the 2010/2011 assessment year

bAssuming a 40% and 5% alcohol content per volume for spirits and beer, respectively

cMost employers in South Africa now operate on a total ‘cost to company’ basis. Thus, employees have a total remuneration package ceiling and must select their medical scheme option, the cost of which is then deducted from the overall package along with other deductions such as pension contributions, and the remainder is then paid as a cash salary

Briefly, two broad categories of taxes have been considered in this paper—direct and indirect taxes. A household’s total annual contribution to indirect taxes is the sum of contributions to value-added tax, fuel levy, and excise taxes on tobacco products, beer, wine and spirits. Annual direct tax contributions have been proxied by personal income tax mainly because of the difficulties in establishing an accurate incidence assumption for corporate income tax. Altogether, the categories of taxes included in this paper make up over 92% of total tax receipts. Direct taxes (including personal and corporate income taxes) and indirect taxes (including value-added tax, fuel levy and excise taxes) make up 21.5% and 16.7% of total health financing, respectively (Table 1). Household annual contributions to private health insurance are the summation of employers’ and employees’ contributions, while out-of-pocket health spending is the annual amount that a household spends out-of-pocket for health services (both public and private) that is not reimbursed by any third-party, including insurance schemes.

Household annual income is measured using total consumption as income data are not very reliable in many developing countries [23], including South Africa. Household income and health payments are further adjusted to account for variations in household size and composition using the adult equivalent (AE) scale [24]:

| 1 |

where is the number of adults in the household, sK is the number of children, is the cost of a child relative to an adult and represents economies of scale. This paper uses and as the values for the parameters. The paper also conducts a detailed sensitivity analysis using different values for the AE scale parameters and .

Analytical Method

Traditionally, income redistribution associated with taxes or health financing () can be written as:

| 2 |

where , a non-negative measure, is income inequality gross of taxes and health care payments (i.e. prepayment income) and , also a non-negative measure, is the same measure of income inequality but net of taxes and health care payments (i.e. post-payment income). When , it implies a pro-poor income redistribution (i.e. inequality in post-payment income is lower than that in prepayment income). A pro-rich redistribution of income from the poor to the rich occurs when , while a proportional income redistribution is equivalent to (at least theoretically).

The seminal work of Aronson et al. [25] provided the following decomposition of the RE of health financing:

| 3 |

where , which could be positive, negative or zero, measures vertical equity or the progressivity or regressivity of the health financing mechanism or system. (which cannot be negative) measures horizontal inequality (i.e. the extent to which ‘equals’ are not treated equally), while (which also cannot be negative) measures reranking (i.e. the extent to which individuals or households change ranks after paying for health services). Both and comprise differential treatment and are non-negative because they contribute to lowering the redistributive potentials of any tax or health financing mechanism or system. The results can also be presented as the percentage contribution of the vertical component to total income redistribution , the horizontal component to total income redistribution , the reranking component to total income redistribution and the percentage contribution of differential treatment to total income redistribution . Recently, Ataguba et al. [26] proposed an alternative decomposition framework where changes in income inequality or the REs of health financing are decomposed into between- and within-group inequality.

The approach suggested in Aronson et al. [25] and some other decompositions of the into , and are based on the Gini index of income inequality [18, 25, 27, 28]. This Gini index-based approach assumes that groups of individuals with an equal income can be obtained from the dataset to represent equals, which is not always the case. While groups of individuals with near equal incomes are created and used in empirical assessments, this presents a challenge in identifying the horizontal and reranking effects.

This paper uses another framework based on the Atkinson-type inequality index to decompose into , and , as in Eq. 3. This approach is adopted to avoid the challenge of creating groups of near equals, used in the Gini index-based decomposition. This alternative decomposition approach referred to in this paper as DJA (Duclos–Jalbert–Araar) [29] has been described extensively elsewhere [30] and has been omitted for brevity. The DJA approach uses nonparametric regressions as opposed to categorising individuals into income bands or groups. Notably, the DJA decomposition in Equation 3 requires a normative choice of values for two parameters, (where ) as a parameter of aversion to horizontal inequality or relative risk aversion [31], and (where ) as a parameter of aversion to reranking or rank inequality. Briefly, is required for a concave utility function with individuals being averse to uncertainty in their post-payment incomes the larger the value of . Similarly, the larger the value of , the more the weight given to the poor’s inequalities compared to the rich. So, indicates whether the society or policymaker attaches more weight to inequalities or relative deprivations occurring at lower ranks than those occurring at higher ranks.

In line with recent empirical assessments of the income RE of health financing using the DJA framework [13, 16, 30], this paper sets and as the suggested ‘reasonable’ values for and [29]. Because external studies guided the choice of values for and , this paper uses different values for the parameters that are within the range suggested for (i.e. between 0.25 and 1.0) and (i.e. between 1.0 and 4.0) [29, 32] to perform robustness and sensitivity analyses. The rationale is to assess the implications of using these specific values or specifically, the robustness analysis assesses the robustness of the estimates of , , and to the choice of values of and that are within the suggested reasonable values.

The original user-written codes obtained from the authors of the DJA approach are modified and executed using Stata® 15 [33]. The standard errors for , , and , which take the sampling structure of the data into account, are obtained using bootstrap methods [34, 35] with 500 replications. Although the paper used a non-cardinal measure of income inequality, the relative contributions of , and to are computed to, among other things, understand the major drivers of income redistribution and to compare the results with those in the literature.

Results

Overall, as shown in Table 2, financing health services through direct taxes induces significant pro-poor income redistribution in South Africa. The RE associated with direct taxes is estimated at 0.0072. This positive and statistically significant reduction in income inequality associated with financing health services via direct taxes resulted from a positive or progressive vertical effect (0.0073) that dominates the negative effects of reranking (< 0.0001) and horizontal inequity (< 0.0001). The results for indirect taxes are the exact opposite, as these taxes increase income inequality in South Africa. The significant pro-rich income redistribution associated with financing health services via indirect taxes (RE = − 0.0025) is less (in absolute terms) than the decrease in income inequality caused by direct taxes. Also, the statistically regressive vertical effect (− 0.0025) dominates the differential treatments caused by reranking (< 0.0001) and horizontal inequity (< 0.0001) for indirect taxes. Financing health services via total taxes (i.e. combining direct and indirect taxes), as shown in Table 2, leads to a significant reduction in income inequality (RE = 0.0048). The significantly progressive vertical effect for total taxes (0.0049) dominates the negative effects of reranking (< 0.0001) and horizontal inequality (< 0.0001). The significant RE for total taxes is a combination of the dominant pro-poor income redistribution associated with direct taxes (RE = 0.0072) and a dominated pro-rich income redistribution associated with indirect taxes (RE = − 0.0025). Therefore, health financing via total taxes contributes to reductions in income inequality in South Africa as they redistribute income from the rich to the poor even though the reverse is the case for indirect taxes.

Table 2:

Redistributive effect of health financing in South Africa, 2010/2011

| Finance mechanism | Share in total financing (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct taxes | 21.5 | 0.7183** (0.0285) | 0.7282** (0.0286) | 0.0046** (0.0009) | 0.0053** (0.0003) | 101.4 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Indirect taxes | 16.7 | − 0.2517** (0.0098) | −0.2491** (0.0097) | 0.0012** (0.0003) | 0.0014** (0.0001) | 99.0 | − 0.5 | − 0.6 |

| Total taxes | 38.2 | 0.4780** (0.0274) | 0.4892** (0.0274) | 0.0053** (0.0009) | 0.0058** (0.0003) | 102.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Private health insurance | 49.9 | 1.0293** (0.0700) | 1.1889** (0.0754) | 0.0641** (0.0041) | 0.0955** (0.0092) | 115.5 | 6.2 | 9.3 |

| Out-of-pocket payments | 12.0 | − 0.0853** (0.0252) | − 0.0647* (0.0262) | 0.0097** (0.0012) | 0.0109** (0.0015) | 75.8 | − 11.3 | − 12.8 |

| Overall health care payments | 1.5188** (0.0869) | 1.7345** (0.0929) | 0.0880** (0.0050) | 0.1277** (0.0109) | 114.2 | 5.8 | 8.4 |

The share in total health financing adds up to 100.1% due to approximations

Bootstrapped standard errors using 500 replications are presented in parenthesis

The values of DJA parameters: and

The values of , , and have been multiplied by 100 to enhance readability

DJA Duclos–Jalbert–Araar, horizontal effect, reranking, redistributive effect, vertical effect

*Statistically significant at the 5% level

** Statistically significant at the 1% level

Private health insurance accounts for about 50% of total health financing, and as shown in Table 2, contributions toward private health insurance reduce income inequality in South Africa. The significant RE (RE = 0.0103) for private health insurance contributions is associated with significantly progressive contributions (vertical effect estimated at 0.0119). Differential treatments in the form of horizontal inequity (0.0006) and reranking (0.0010) are also statistically significant. The results in Table 2 show that the income RE associated with private health insurance contributions is greater than that resulting from total taxes. Because private health insurance members are the richest South Africans, the redistribution in income observed here is mainly occurring among the rich.

Out-of-pocket health spending, representing about 12% of total health financing, significantly increases income inequality, albeit at a lower magnitude than indirect taxes. The statistically significant pro-rich income RE (RE = − 0.0009) for out-of-pocket health spending is mainly associated with it being mildly regressive (vertical effect estimated at − 0.0006). Horizontal inequality (0.0001) and reranking (0.0001) are also statistically significant but dominated by the vertical effect.

Overall, health financing in South Africa contributes significantly to reducing income inequality (Table 2). The overall pro-poor RE of health financing is estimated at 0.0152, and it is associated with a significantly progressive (vertical effect = 0.0173) overall payment that dominates the horizontal inequity (0.0009) and reranking (0.0013) effects. The reduction in income inequality resulting from overall health financing is the combined effect of the pro-poor income redistribution for total taxes and private health insurance and the pro-rich redistribution for out-of-pocket health payments. The increase in inequality associated with out-of-pocket health spending (RE = − 0.0009), although statistically significant, is small relative to the decreases in income inequality induced by total taxes (RE = 0.0048) and private health insurance (RE = 0.0103). The resultant effect is a significant pro-poor RE of total health financing in South Africa.

Table 2 also presents the relative contributions of the different components to the overall income redistribution. These ratios represent another way of presenting the results to show the major income redistribution drivers [17]. In the absence of differential treatment, direct taxes would have been 1.4% more redistributive, with reranking and horizontal inequity accounting for 0.7% and 0.6% of the differential effect, respectively. For indirect taxes, income redistribution would have been about 1.1% less pro-rich in the absence of differential treatment. About 0.6% of this is attributed to reranking, while 0.5% is due to unequal treatment of equals. Financing health services via total taxes would have reduced income inequality by a further 2.3% in the absence of differential treatments. A slightly larger share (1.2%) comes from the reranking of households, while about 1.1% comes from horizontal inequity. Similarly, for private health insurance, about a 15.5% further reduction in income inequality would have been observed in South Africa in the absence of differential treatment of households. Although the vertical component dominates, 9.3% of the differential treatment is accounted for by reranking of households and 6.2% is due to horizontal inequity in private health insurance contributions. The negative income redistribution (i.e. increase in income inequality) associated with out-of-pocket health spending would have been about 24.2% less pro-rich in the absence of differential treatment of households. Reranking alone accounts for about 12.8% of this effect, while horizontal inequity accounts for 11.3%. All these effects put together as shown in Table 2 indicate that overall health financing could have been 14.2% more redistributive in the absence of differential treatment of households. Over 8% of the differential treatment effect in overall health financing comes from the reranking of households.

Sensitivity and Robustness Checks

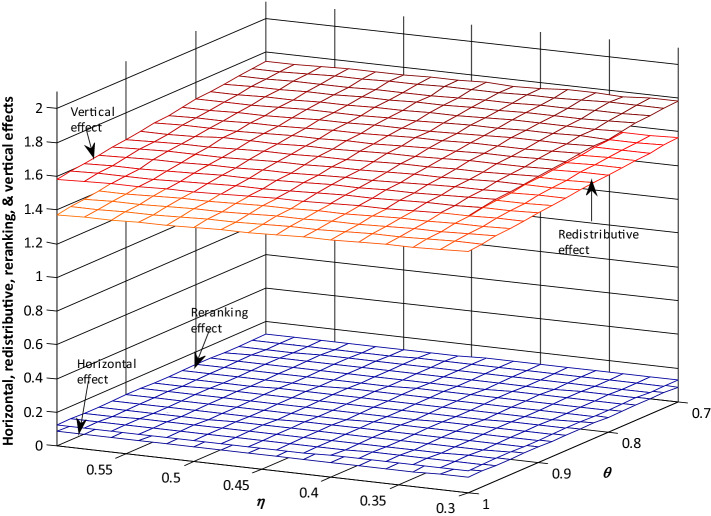

The results in Table 2 are based on certain assumptions about the parameters of aversion to reranking () and horizontal inequality (). Sensitivity analysis (Figure 1) shows that the choice of values of and have some impact on the estimated effects, especially at the extreme values. However, using parameter values that are close to the ‘reasonable’ values of and , the results remain robust to the choice of parameter values. This means that the overall results in Table 2 and the conclusions remain the same, as the parameter values did not significantly affect the results.

Fig. 1.

The effect of DJA parameters values on the estimated vertical, horizontal, reranking and redistributive effects of health financing, South Africa, 2010/2011. The values of the redistributive, vertical, horizontal and reranking effects have been multiplied by 100 to enhance readability. DJA Duclos–Jalbert–Araar, parameter of aversion to reranking or rank inequality; parameter of aversion to horizontal inequality or relative risk aversion

Also, certain assumptions about the AE scale parameters guide the estimates reported in Table 2. In Table 2, eta (), the cost of children parameter, and theta (), the economies of scale parameter, are set at 0.50 and 0.75, respectively. Per capita estimates will be obtained by setting , as becomes total household size (see Eq. 1). When , a child’s consumption is assumed to be almost equivalent to that of an adult, while is a case where economies of scale are ignored and larger households, on average, do not live more cheaply compared to smaller households. The suggestion in Deaton and Zaidi [24] guides the choice of values for the robustness checks. For developing countries, the value of should lie between 0.75 and 1, while the value of should lie between 0.3 and 0.5. As seen in Fig. 2, the choice of parameter values for and has a very limited impact on the estimated effects (, , and ), meaning that the results are robust to the choice of AE scale parameters.

Fig. 2.

The effect of different adult equivalent scale parameters on the horizontal, reranking, vertical and redistributive effects of health financing, South Africa, 2010/2011. The values of DJA parameters: and . The values of the redistributive, vertical, horizontal and reranking effects have been multiplied by 100 to enhance readability. DJA Duclos–Jalbert–Araar, = parameter for the cost of a child relative to an adult; = economies of scale parameter

Discussion

This paper demonstrates that overall health financing in South Africa and financing health services through private health insurance, direct taxes and total taxes contribute to significant reductions in income inequality. On the other hand, financing health services through out-of-pocket spending and indirect taxes increases income inequality significantly. The negative income redistribution associated with indirect taxes reported in this paper is consistent with results reported elsewhere, including in Argentina (in 2002), Italy (in 1991), Portugal (in 1990) and the United Kingdom (in 1992) [13, 15]. On the contrary, a positive effect was estimated in 2010 for Zambia [30], and the authors attributed this to a largely informal economy where the poor easily escape indirect taxes on goods and services by purchasing items in informal markets. In all previous studies, the vertical effect is the major driver of the income redistribution associated with indirect taxes. In some countries such as Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland the pro-rich vertical effect accounts for almost all of the negative income redistribution [15, 17]. Generally, between 60% and 100% of the pro-rich income redistribution is attributed to the regressive vertical effect in indirect taxes. In South Africa, the vertical effect contributed about 99%, while differential treatments accounted for about 1% of the loss in income redistributive power of indirect taxes used in financing health services. The differential treatment for indirect taxes in South Africa can be attributed mainly to the non-discriminatory nature of indirect taxes. It could also be associated, to a lesser extent, with the consumption patterns that exist among households with similar incomes.

Internationally, reductions in income inequality are usually associated with financing health services via direct taxes. This result is similar in South Africa, with a dominant vertical effect. The positive RE of direct taxes is mainly the result of progressive direct taxes. Although some of these are based on old data, direct taxes were progressive in Argentina, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States and Zambia, with the contribution of the vertical effect to overall redistribution ranging between 100% and 143% [13, 15–18, 30].

Combining the largely pro-rich income redistribution associated with indirect taxes and a pro-poor income redistribution associated with direct taxes, a pro-poor income RE for total taxes emerged in South Africa. The result was similar in Denmark (in 1987), Switzerland (1992) and Zambia (2010), where the pro-poor vertical effect dominates the horizontal and reranking effects [15, 30]. There were no statistically significant differential treatments in countries like Germany, Italy and the Netherlands as ~ 100% of the RE comes from a progressive vertical effect of total taxes. Generally, most studies conclude that total taxes would have been between 2% and 18% more redistributive in the absence of differential treatment in financing health services.

In South Africa, the reduction in income inequality linked to private health insurance is related to the distribution of the enrolees. It is essential to bear in mind that unlike total taxes where almost all residents may be entitled to services provided at public facilities (especially at the primary health care level where services are free of charge), it is only those who are members of a private health insurance scheme in South Africa that access benefits associated with being insured [36]. In fact, because poor households do not purchase private health insurance, they do not benefit from contributions to private health insurance. The differential treatment (reranking and horizontal inequity) for private health insurance in South Africa is attributed mainly to individuals facing the same premium schedule irrespective of income levels and how households select members within their household for insurance cover [37]. However, some individuals mitigate this by choosing lower cost and less generous service benefit options. This could have accounted for the smaller than expected differential treatments observed. Elsewhere, the income RE associated with private health insurance can be negative or positive depending on the nature of health insurance in the country (i.e. how premiums are structured and paid for, whether the insurance is supplementary or not, whether it is only the rich who are covered, whether enrolment is for individuals or households, etc.) [13, 15]. Whether private health insurance induces a pro-rich or pro-poor income redistribution, the vertical effect dominates the horizontal and reranking effects.

The negative RE associated with out-of-pocket health spending in South Africa is similar to that in Switzerland, the Netherlands, Vietnam and the West Bank (Palestine) [15, 38, 39]. In the case of South Africa, even though out-of-pocket health spending comprises 12% of total health financing, the pro-rich income redistribution induced is not equitable and would reduce the extent to which overall health financing favourably redistributes income. Large and significant differential treatment associated with out-of-pocket health spending in South Africa can be described as inequitable because of the stochastic nature of illnesses and the non-discriminatory nature of out-of-pocket health spending. Some individuals with the same income level could randomly fall sick, which will inherently create randomness in out-of-pocket health spending. Although there are cases where out-of-pocket health spending results in substantial differential treatment, again, most studies show that the vertical effect substantially dominates the horizontal and reranking effects [16, 17]. It is important to note that some studies have reported negative income redistribution with out-of-pocket health spending but with a progressive vertical effect (see [13, 40]). In such countries, the combined horizontal and reranking effects dominate the progressive vertical effect. In Argentina (in 2002) and Zambia (in 2010), out-of-pocket health spending was progressive, inducing a pro-poor income redistribution [13, 30].

The significant reduction in income inequality associated with total health financing in South Africa is comparable to that reported in some countries like Argentina, France, Italy, Sweden and Zambia (see [13, 15, 18, 30]). However, countries like Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Palestine, Portugal, Switzerland and the United States (see [15–17, 38, 41]) record negative income redistribution for total health financing, caused mainly by regressive vertical effects. Irrespective of the nature of income redistribution caused by total health financing, the progressive or regressive vertical effect generally dominates. In the case of South Africa, the pro-poor income redistribution associated with total health financing can be attributed to the pro-poor private health insurance and total taxes.

South Africa has made significant efforts to implement the National Health Insurance (NHI) to improve UHC and guarantee access to health services for its population [42–44]. Now, what do these results mean for UHC in South Africa, mainly as the country aims to roll out the NHI and reduce income inequality substantially by 2030 [12]? In addition to the high level of inequality in income and access to social services, a significant challenge facing the country is the skewed distribution of resources between the private and public sectors relative to the population that each serves [45]. So, let us take a look at both the private and public health sectors to understand the implications of the results. South Africa’s private health sector is financed mainly through voluntary private health insurance. Private health insurance membership in the country, estimated at less than 20% of the population, is skewed towards households in the top two quintiles, reflecting the benefiting group. The result that private health insurance contributions may reduce income inequality, as shown in this paper, is primarily because the poor do not belong to these schemes and do not benefit from such contributions. Therefore, expanding private health insurance scheme membership, especially among the lower socioeconomic groups in South Africa will make private health insurance contributions a less pro-poor health financing mechanism [47], and is an unfavourable way to achieve UHC [46]. The other private health financing mechanism is out-of-pocket health spending, which is the most fragmented mechanism, where funds are not pooled. Currently, out-of-pocket health spending in South Africa leads to minimal financial catastrophe and impoverishment [48], which could increase substantially if the share of out-of-pocket health spending in current health expenditure is allowed to increase [6]. Because private health insurance and out-of-pocket health spending are not ideal for achieving favourable income redistribution and UHC, let us examine public sector financing.

Compared to other options, a country’s “predominant reliance on compulsory or public financing is essential for universal coverage” ([46], p. 867). This means that taxes, the main public financing arrangement in South Africa, are a potentially viable option to ensure ‘real’ reductions in income inequality. The significant contribution of labour income to income inequality [10] also provides a justification to finance health services using progressive income taxes that positively redistribute income favouring the poor. In fact, the NHI is designed to be financed predominantly through tax revenue [43, 44], which also includes the funds to be shifted from the provincial equitable share and conditional grants that usually go to provinces to provide health services in the country (Table 3). The tax revenue will come from direct and indirect taxes and other ‘taxes’ such as payroll tax and a surcharge on personal income tax. International evidence on the progressivity and pro-poor income redistribution of total taxes reported in this paper and the overall benefits of using taxes to finance services (see also [49]) lend support that using progressive taxes to finance health services in South Africa will continue to lead to a significant reduction in income inequality. However, this is not the same for all taxes. Indirect taxes, including value-added tax and excise taxes, are regressive in South Africa [50] and may continue to increase income inequality—an outcome that does not align with the National Development Plan’s agenda to reduce income inequality. Interestingly, rather than increasing the value-added tax rate or using another form of indirect tax, the other ‘special’ taxes on payroll and a surcharge on personal income proposed in Table 3 to finance the NHI are forms of direct taxes, which have a pro-poor income redistributive effect.

Table 3.

Proposed sources of revenue for the National Health Insurance, South Africa

| Tax revenue | Non-tax revenue sources |

|---|---|

|

Direct taxation Indirect taxation Payroll taxation (employer and employee) Earmarked surcharge on personal income tax |

Shifting funds from the provincial equitable share and conditional grants Reallocating funds for medical scheme tax credits from various medical schemes Fines Interest or return on the fund’s investment Money paid erroneously into the fund Bequest, donations or other funds Premiums |

Increased reliance on taxes does not necessarily imply increasing tax rates per se. The National Health Insurance Bill (NHI Bill) notes, for example, that the current fiscal conditions, further aggravated by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [51], mean that increasing tax rates and initiating new taxation options such as a surcharge on income tax and a small payroll tax cannot be an immediate option, but should be considered at a later stage of implementing the NHI [44]. While tax rates cannot be raised immediately, there is room for sustaining and expanding revenue collection, increasing the share of tax revenue allocated to the health sector, and sustaining gross domestic product (GDP) growth. For example, South Africa witnessed “[e]xtensive tax reform and more efficient tax collection [that] have expanded revenue, permitting lower tax rates for both individuals and companies, and personal tax relief” ([52] p.745). As NHI policy takes shape and with the deliberation of the NHI Bill at Parliament, there needs to be greater consideration for the high level of income inequality in the country and recognition that health financing reforms can contribute to reducing income inequality in South Africa, especially when the benefits from using the services are also favourably distributed [19, 47]. This can be achieved by, among other things, financing the health system using equitable financing mechanisms that induce pro-poor income redistribution to provide everyone with equitable access to health services.

Limitations

Firstly, the paper did not account for less than 10% of taxes. These are mainly indirect taxes that might induce a pro-rich income redistribution. Because this is a very small proportion of total taxes, it is expected to have a minimal impact on the overall results. Secondly, due to difficulties in obtaining more accurate estimates for corporate income tax contributions, personal income tax is used to proxy direct taxes. Generally, while companies bear the statutory burden of corporate income tax, the final burden may be shifted ‘forward’ to consumers in the form of higher prices, with a resulting regressive pattern, or may sometimes be shifted ‘backwards’ to recipients of capital income, in which case, the tax is progressive ([53] p. 536). Some studies deliberately exclude corporate income tax or remain silent on its treatment [15, 54–56]. For this paper, the 2010/2011 IES data do not contain reliable information on capital income, for example, that could be used to estimate the contributions for capital owners. In this paper, corporate income tax is assumed to be progressive, perhaps to a lesser extent than the progressivity of personal income tax, which may reduce the overall pro-poor income redistribution, albeit to a very small degree. Thirdly, private health insurance is not homogenous in South Africa. About 80 different medical schemes are operating in the country with different benefit options [57]. This paper has not been able to account for this directly in the estimation, but it is captured indirectly through the differential treatment of households. Fourthly, contributions to private health insurance are tax-deductible. Ideally, these contributions should be deducted from gross personal income before computing total personal income tax contributions. This is impossible because contributions to private health insurance are collected at the household level, while personal income tax is computed at the individual level. Because it is the richest South Africans that purchase private health insurance, this may reduce the pro-poor income redistribution (and vertical effect) computed for direct taxes, but very slightly. Fifthly, it is ideal to assess the implications of health financing on overall wellbeing rather than focusing on income inequality [19]. Lastly, although the paper uses data from 2010/2011, many important indicators have remained relatively similar over the past decade. For example, the share of the various health financing mechanisms remained similar over the past decade [14], and informal employment accounted for about 16–18% of total employment between 2011 and 2019 [58, 59]. These limitations notwithstanding, the results from South Africa compare with those reported elsewhere, as discussed above. More importantly, the results point to health financing mechanisms that contribute to substantial increases or reductions in income inequality, which is crucial for health financing policy in South Africa.

Conclusion

The empirical results in this paper are relevant for the current NHI policy in South Africa and the global move towards UHC as enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals. The health system has a role in ensuring significant income inequality reductions to meet the target set in the country’s National Development Plan. This will require a very well-designed progressive health financing system that places a lesser burden on the poor relative to the rich, which guarantees access to quality health services based on need.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with financial and scientific support from the Partnership for Economic Policy (PEP), with funding from the Department for International Development (DFID) of the United Kingdom (or UK Aid), and the Government of Canada through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The author acknowledges the assistance from Abdelkrim Araar and Jean-Yves Duclos regarding provision of the original Stata ado-file, Jörgen Levin for his comments on earlier drafts, and the participants at the 7–8 November 2019 workshop on taxation for inclusive development, at the Nordic Africa Institute, University of Uppsala.

Declarations

This paper uses publicly available data that have received ethics approval. Thus, there are no ethical issues.

Funding

John E. Ataguba is supported by the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation. Financial assistance was also received from the Partnership for Economic Policy (PEP), with funding from the Department for International Development (DFID) of the United Kingdom (or UK Aid), and the Government of Canada through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC).

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest exist.

Ethics approval

This paper uses publicly available data that have received ethics approval. Thus, there are no ethical issues.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability

The dataset used in this paper is available at https://datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/316/get_microdata.

Code availability

Dr. Abdelkrim Araar provided the original Stata ado-file used in this paper.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2013: Research for universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240690837.

- 2.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2010 - Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44371/9789241564021_eng.pdf?sequence=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Ataguba JE, Ingabire M-G. Universal health coverage: assessing service coverage and financial protection for all. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1780–1781. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ataguba JE, Asante AD, Limwattananon S, Wiseman V. How to do (or not to do)… a health financing incidence analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(3):436–444. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIntyre D, Obse AG, Barasa EW, Ataguba JE. Challenges in financing universal health coverage in sub-Saharan Africa. Oxf Res Encycl Econ Finance. 2018;2018(5):1–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills A, Ataguba JE, Akazili J, Borghi J, Garshong B, Makawia S, et al. Equity in financing and use of health care in Ghana, South Africa, and Tanzania: implications for paths to universal coverage. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):126–133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Treasury. Budget Review 2012. Pretoria: National Treasury; 2012. http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2012/review/FullReview.pdf.

- 8.Gilson L, McIntyre D. Post-apartheid challenges: household access and use of health care in South Africa. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37(4):673–691. doi: 10.2190/HS.37.4.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McIntyre D, Doherty JE, Ataguba JE. Health care financing and expenditure: post-1994 progress and remaining challenges. In: Van Rensburg HCJ, editor. Health and health care in South Africa. Pretoria: Van Schaik; 2012.

- 10.Hundenborn J, Leibbrandt MV, Woolard I. Drivers of inequality in South Africa. Helsinki: The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), 2018. https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/drivers-inequality-south-africa9292566040.

- 11.Statistics South Africa. Inequality Trends in South Africa: A Multidimensional Diagnostic of Inequality. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2019. https://www.afd.fr/sites/afd/files/2019-11-10-11-57/report-inequality-trends-in-south-africa.pdf.

- 12.Statistics South Africa. Poverty Trends in South Africa: an examination of absolute poverty between 2006 and 2015. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2017. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-06/Report-03-10-062015.pdf.

- 13.Cavagnero E, Bilger M. Equity during an economic crisis: financing of the Argentine health system. J Health Econ. 2010;29(4):479–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Global health expenditure database Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 2020 5 January]. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/ViewData/Indicators/en.

- 15.van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, van der Burg H, Christiansen T, Citoni G, Di Biase R, et al. The redistributive effect of health care finance in twelve OECD countries. J Health Econ. 1999;18(3):291–313. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(98)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilger M. Progressivity, horizontal inequality and reranking caused by health system financing: a decomposition analysis for Switzerland. J Health Econ. 2008;27(6):1582–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Progressivity, horizontal equity and reranking in health care finance: a decomposition analysis for the Netherlands. J Health Econ. 1997;16(5):499–516. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(97)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerdtham U-G, Sundberg G. Redistributive effects of Swedish health care finance. Int J Health Plan Manag. 1998;13(4):289–306. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1751(199810/12)13:4<289::AID-HPM524>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleurbaey M, Schokkaert E. Equity in health and health care. In: Pauly MV, McGuire TG, Barros PP, editors. Handbook of health economics. Waltham: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 1003–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutzin J. Health financing for universal coverage and health system performance: concepts and implications for policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(8):602–611. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.113985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statistics South Africa. Income and expenditure of households 2010/2011: statistical release P0100. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2012. http://beta2.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0100/P01002011.pdf.

- 22.Ataguba JE, McIntyre D. The incidence of health financing in South Africa: findings from a recent data set. Health Econ Policy Law. 2018;13(1):68–91. doi: 10.1017/S1744133117000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Donnell O, van Doorslaer E, Rannan-Eliya RP, Somanathan A, Adhikari SR, Akkazieva B, et al. Who pays for health care in Asia? J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):460–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deaton A, Zaidi S. Guidelines for constructing consumption aggregates for welfare analysis. LSMS Working Paper No 135. Washington D.C.: World Bank Publications; 2002. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/14101.

- 25.Aronson JR, Johnson P, Lambert PJ. Redistributive effect and unequal income tax treatment. Econ J. 1994;104(423):262–270. doi: 10.2307/2234747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ataguba JE, Ichoku HE, Nwosu CO, Akazili J. An alternative approach to decomposing the redistributive effect of health financing between and within groups using the Gini index: the case of out-of-pocket payments in Nigeria. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18:747–757. doi: 10.1007/s40258-019-00520-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urban I, Lambert PJ. Redistribution, horizontal inequity, and reranking: how to measure them properly. Public Finance Rev. 2008;36(5):563–587. doi: 10.1177/1091142107308295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van de Ven J, Creedy J, Lambert PJ. Close equals and calculation of the vertical, horizontal and reranking effects of taxation. Oxf Bull Econ Stat. 2001;63(3):381–394. doi: 10.1111/1468-0084.00226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duclos J-Y, Jalbert V, Araar A. Classical horizontal inequity and reranking: an integrated approach. In: Amiel Y, Bishop JA, editors. Fiscal policy, inequality and welfare (research on economic inequality) Bingley: Emerald Group; 2003. pp. 65–100. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulenga A, Ataguba JE. Assessing income redistributive effect of health financing in Zambia. Soc Sci Med. 2017;189:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atkinson AB. On the measurement of inequality. J Econ Theory. 1970;2(3):244–263. doi: 10.1016/0022-0531(70)90039-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duclos J-Y. Gini indices and the redistribution of income. Int Tax Public Finance. 2000;7(2):141–162. doi: 10.1023/A:1008700419908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.StataCorp. Stata: release 15—Statistical software. College Station: StataCorp LP; 2017.

- 34.Efron B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J Am Stat Assoc. 1987;82:171–185. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1987.10478410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Efron B, Tibshirani R. Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Stat Sci. 1986;1(1):54–75. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ataguba JE, McIntyre D. Who benefits from health services in South Africa? Health Econ Policy Law. 2013;8(1):21–46. doi: 10.1017/S1744133112000060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Govender V, Ataguba JE, Alaba OA. Health insurance coverage within households: the case of private health insurance in South Africa. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract. 2014;39(4):712–726. doi: 10.1057/gpp.2014.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abu-Zaineh M, Mataria A, Luchini S, Jean-Paul M. Equity in health care finance in Palestine: the triple effects revealed. J Health Econ. 2009;28(6):1071–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Paying for health care: quantifying fairness, catastrophe and impoverishment, with applications to Vietnam, 1993-98. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2715. Washington D.C.: World Bank; 2001. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2444000.

- 40.Ichoku HE. A distributional analysis of healthcare financing in a developing country: a Nigerian case study applying a decomposable Gini index. Cape Town: PhD thesis, University of Cape Town; 2006.

- 41.Abu-Zaineh M, Mataria A, Luchini S, Jean-Paul M. Equity in health care financing in Palestine: the value-added of the disaggregated approach. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2308–2320. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Department of Health. National Health Act (61/2003): policy on National Health Insurance. Government Gazette 34523. Pretoria: National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa; 2011.

- 43.National Department of Health. National Health Insurance for South Africa: towards Universal Health Coverage. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2015. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201512/39506gon1230.pdf.

- 44.Republic of South Africa. National Health Insurance Bill. Pretoria: Government of South Africa; 2019. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201908/national-health-insurance-bill-b-11-2019.pdf.

- 45.McIntyre D, Thiede M, Nkosi M, Mutyambizi V, Castillo-Riquelme M, Gilson L, et al. A critical analysis of the current South African health system. Cape Town: Health Economics Unit, University of Cape Town and Centre for Health Policy, University of the Witwatersrand; 2007.

- 46.Kutzin J. Anything goes on the path to universal health coverage? No. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:867–868. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.113654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McIntyre D, Ataguba JE. Modelling the affordability and distributional implications of future health care financing options in South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(suppl 1):i101–i112. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koch SF, Setshegetso N. Catastrophic health expenditures arising from out-of-pocket payments: Evidence from South African income and expenditure surveys. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prakongsai P, Tangcharoensathien V, Tisayatikom K. Who benefit from government health spending before and after universal coverage in Thailand? J Health Sci. 2007;16:S20–S36. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1070281

- 50.Ataguba JE. Assessing equitable health financing for universal health coverage: a case study of South Africa. Appl Econ. 2016;48(35):3293–3306. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2015.1137549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ataguba JE. COVID-19 pandemic, a war to be won: understanding its economic implications for Africa. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18:325–328. doi: 10.1007/s40258-020-00580-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ajam T, Janine A. Fiscal renaissance in a democratic South Africa. J Afr Econ. 2007;16(5):745–781. doi: 10.1093/jae/ejm014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shah A, Whalley J. Tax incidence analysis of developing countries: an alternative view. World Bank Econ Rev. 1991;5(3):535–552. doi: 10.1093/wber/5.3.535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simkins C, Woolard I, Thompson K. An analysis of the burden of taxes in the South African economy for the years between 1995/96 and 1999/2000. Pretoria: South African Department of Finance; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Younger SD, Sahn DE, Haggblade S, Dorosh PA. Tax incidence in Madagascar: an analysis using household data. World Bank Econ Rev. 1999;13(2):303–331. doi: 10.1093/wber/13.2.303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Auerbach AJ. Who bears the corporate tax? A review of what we know. In: Poterba JM, editor. Tax policy and the economy. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Council for Medical Schemes. Council for Medical Schemes annual report 2017-2018. Pretoria: Council for Medical Schemes; 2018. https://www.medicalschemes.com/files/Annual%20Reports/CMS_AnnualReport2017-2018.pdf.

- 58.Statistics South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey, third quarter 2019. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2019. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02113rdQuarter2019.pdf.

- 59.Statistics South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey, first quarter 2011. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2011. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02111stQuarter2011.pdf.

- 60.Ataguba JE, McIntyre D. The incidence of health financing in South Africa: findings from a recent dataset. Health Econ Policy Law. 2018;13(1):68–91. doi: 10.1017/S1744133117000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this paper is available at https://datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/316/get_microdata.