Abstract

Background and aim of the work.

Psychosocial needs in cancer patients seem to be underestimated and undertreated. The present research was designed to explore under-considered psychosocial needs (e.g., stressful life events, perceived social support, sense of mastery and depressive/anxious symptoms) of a female cancer group. The aim of the study was to test an assessment psycho-oncological model for female cancer patients. An assessment model of psychosocial needs and Stressful Life Events was operationalized and tests its predictive power.

Methods.

We used Discriminant Analysis to test predictive power of the model and of the single variables included in it. 236 oncological patients (mean age 55.50 ± 13.09) were matched with 232 healthy control groups in the study. The following instruments were chosen: the Florence Psychiatric Interview, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, Beck Depression Inventory I, and Sense of Mastery.

Results.

The model satisfied the assumption criteria and was significant (Ʌ= .680, X2 = 109.73, p< .001).

Conclusions.

Stressful events, depression and anxiety were adequate markers of the assessment psycho-oncological model proposed for female cancer patients. The present study provides contributions in a clinical perspective: the results support the relevance of considering an assessment psychosocial model to use in female oncology for an accurate estimation of the women’s needs. Women affected by female cancer with an history of Stressful Early and Recent life events and high level of anxiety and depression could positively benefit from a psychotherapy treatment. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Stressful Life Events, Female Cancer, Psychosocial Factors, Psychoncology

Background

According to the recent literature, psychosocial needs in cancer patients seem to be underestimated and undertreated (1-5). Under-considered psychosocial needs can affect distress level, patient’s quality of life and adherence to treatment (1, 4, 5). Some psychosocial dimensions may contribute to distress intensity related to cancer treatment: lack of social support, low sense of mastery, affective disorders, other stressors (e.g., concurrent stressful life events and comorbid conditions), lack of economic resources, and individual characteristics (6-10). Over the past 30 years, stressful life events have been used as a measure for quantifying stress (11, 12). Several discussions have been proposed to explain the mechanism by which social support influences the impact of stressful life events on adjustment (13-16). Stressful events occurring in the presence of social support are assumed to produce less distress relative to events occurring in the absence of social support (17-19). In physical diseases and psychopathology, social support is a relevant and protective factor that can mediate adaptation in patients suffering from a disease (20-23).

Despite the fact that previous research has clearly demonstrated the association between different stress-related psychosocial factors and cancer (24), no study has implemented an integrated model of psychosocial needs (i.e. Early Life Events, Recent Life Events, depressive and anxious symptomatology, perceived social support and sense of mastery) in female cancer patients (female suffering from Breast, Endometrial and Ovary cancer), a population particularly vulnerable to psychosocial distress (24, 25).

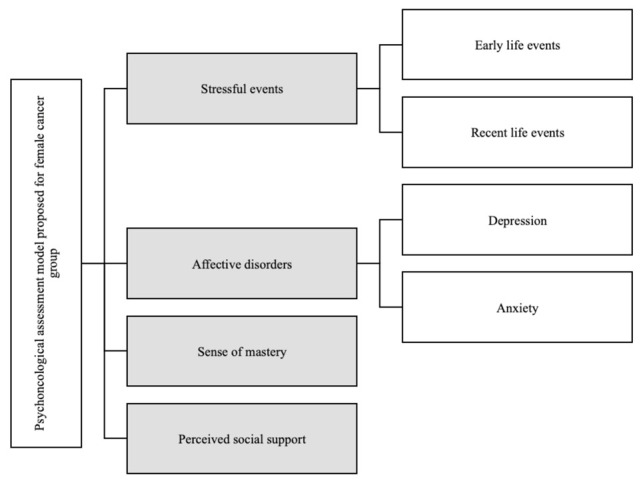

To fill up this gap, we proposed and implemented a psychosocial model for assessment procedure (Figure 1) inspired by dimensions suggested by literature (24-26), to investigate what psychosocial factors can discriminate between an oncological and a control group. To our Knowledge do not exist a study focus on psychological assessment for female cancer group. The psychological condition of this target was considered and discussed in literature (3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 17, 18, 24) but to our knowledge do not exists a shared specific assessment procedure. The prevalence of psychological disorders in patients with cancer range from 29% to 47%, including anxiety, depression, adjustment disorders, and other psychiatric diagnoses that would likely be induced by medication and general medical condition (3, 4, 6, 8). Such psychiatric complications and psychological challenges impair adjustment capabilities and quality of life of the patient, and also negatively affect the course of disease and response to treatment (8). Stress and related psychosocial factors are associated with cancer incidence, survival and mortality (10, 11, 24). Social support was found to enable women with cancer to cope with stress and with their disease, to psychologically adapt to cancer-related stressors and to have enhanced quality of life (17,18). Given the importance of the above-mentioned psychosocial factor among female cancer patients, it seems relevant to systematically explore them by developing a specific assessment method.

Figure 1.

Psychoncological assessment model tested on female cancer group

Methods

Aims

The aim of the current study is to test a model for assessment procedure of psychoncological factors in female oncology. Specifically, the purpose is to determine the extent to which the theoretical model is consistent with the already consolidated literature on this topic (3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 17, 18, 24).

Research Design and Participants

A case-control study was designed. The study enrolled 236 women suffering from female cancer (breast cancer, ovarian cancer, endometrial) hospitalized or in Day Hospital treatment between January 2009 to January 2011. The sample was selected among women admitted to Gynaecological oncology and Breast Unit, both afferent to Careggi University Hospital (Florence, Italy). Exclusion criteria were age <18 and >75 years, intellectual disability, and not fluent in Italian.

A control group of 232 healthy women was recruited by a convenience sampling (matched for age and education to the clinical group). It was selected using a case-control method from a pool of 1077 subjects representative of the general population living in the same area (the region of Tuscany, central Italy). These were randomly recruited from the regional lists of the Italian National Health System (99.7% of the citizens are included in the list of the NHS).

The inclusion criteria for controls were being free of cancer or other malignant disease and living in the same geographical area of the clinical population (the region of Tuscany, central Italy). The mean age of the control group was 53.75 (SD = 13.6) years whereas the mean age of the clinical group was 55.50 (SD = 13.09) years. The level of education was 10.57(SD = 4.5) years for the control group and 10.76(SD = 4.39) for the clinical group.

Measures

Data collection was implemented considered the model of assessment proposed (Figure 1), using semi-structured interviews and written tools. A quantitative approach was used, because the data extract from interviews was the presence or absence of traumatic events. The qualitative data was therefore treated only with a quantitative way. The instruments were filled out in hospital for clinical group and at participants’ home for control group. Socio-demographic variables and a medical history, including oncological diagnosis, age of onset, stage of cancer, current and past treatments (e.g., chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgical operation) were also collected.

Stressful Events

The Early Life Events and Recent Life Events were assessed by means of the Florence Psychiatric Interview (FPI), a validated semi-structured interview (27). In particular, respondents were asked whether they had experienced the following types of adversity before the age of 15 (e.g, early life events): death of, or separation from, mother; death of, or separation from, father; loss and severe illness of any other cohabiting relative and severe illness in the subject’s childhood sufficient to interfere with the development of normal social relationships. Personal accounts were recorded extensively, including the contexts, circumstances, and timing of any specific adversity. Stressful events of the year before the onset of the illness (the year before the interview in the case of control subjects) (i.e., recent life events), as well as the circumstances and the context in which they occurred were also explored by means of the interview. This procedure, which has been used in the past (e.g., 9, 10) has proven reliable.

The early and recent live events was then transformed in in two continuous variables. The first was a cumulative effect of the Stressful Early Life Events (in which we included death of, or separation from mother; death of, or separation from, father; loss and severe illness of any other cohabiting relative) and the second was a cumulative effect of Stressful Recent Life Events (in which we included: family conflicts, bereavement, loss of job/financial problems, health problems, and sexual and/or physical abuse).

Anxiety, Depression, Social Support and Sense of Mastery

Sense of mastery, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and social support were assessed using the Italian versions of the Sense of Mastery Scale [SOM] (28), of the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale [HADS] (29), of the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI] (30) and of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [MSPSS] (31).The Italian version (32) of the Sense of Mastery Scale (28) assesses the global belief in one’s ability to control things and to mitigate adverse aversive events (28). The scale contains 7 items (e.g., “What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me”) which are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = “Strongly agree” to 7 =”Strongly disagree”. The total scores range from 7 to 49 with higher scores indicate a higher level of self-mastery (32).

The Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale [HADS] (29) is a 14-item self-report questionnaire on a 4-point Likert scale. The questionnaire includes depression and anxiety subscales (7 items for each). The total score ranges from 0 to 42 for all the 14 items, and each subscale (depression and anxiety) is scored from 0 to 21. The HADS is a useful self-report measure of the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in primary care patients and in the general population (33). The HADS has shown good psychometric properties as a measure to assess depressive and anxiety symptoms in Italian samples (34). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) measures patients’ s perceived social support. The MSPSS assesses perceptions of three dimensions: social support adequacy from family, friends, and significant others. The three scales are composed is by four items each. This 12–item scale uses a 7–point Likert type response format (1= very strongly disagree; 7= very strongly agree). A higher score indicates better perceived social support (31). The Italian version of the MSPSS has shown good psychometric properties (35). The Beck Depression Inventory II [BDI] (30) quantitatively assesses the depressive symptoms perceived by the patient. It consists of 21 sentence groups and was independently completed by the patient. Each item is rated on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3; its total score ranges from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. It explores the affective, cognitive, motivational, vegetative, and psychomotor components of depression. Each item comprises a list of four statements arranged by the increasing severity of a symptom of depression: the higher the score, the higher the severity of depressive symptoms. Excellent psychometric properties of the BDI-II on Italian individuals were found (36).

Data Analysis

The interviews were transcript and examined by qualified independent investigators, not involved in the interviews and blind to the participants’ group status. They rated whether each descriptive account had to be considered a stressful event.

The descriptive Statistics of the Psychosocial Variables were compared by One way ANOVA.

The data file was inspected for missing data and normality of the distribution. There were no missing data and the respect of Multivariate Normality was checked by Mahalanobis distance. To test the theoretical model, a discriminant function (DA), was used.

Discriminant Analysis (37) is useful when a set of independent continuous variables are expected to predict an outcome that is expressed by a categorical dependent variable; here we are interested in exploring a Discriminant Model in which the outcome variable is the Group (Female Cancer Group vs Control Group) while a set of psychosocial and clinical variables are considered as predictors. Discriminant Analysis provides an estimate of the classification power of the overall set of predictors together with estimate of the relative contribution (weight) of each variable to the variation of the outcome.

A linear combination of the predictor variables that provide the best discrimination between the groups was tested. Discriminant analysis is appropriate when wishing to predict in which group (in this paper, those who belongs to clinical or healthy group) participants will be collocated. Our model of markers tested by DA included the Cumulative Effect of Early Life Events, cumulative effect of Recent Life Events, Anxiety scale (HADS), Depression scale (HADS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Friends Social Perceived Support, Family Social Perceived Support, Others Social Perceived Support (MSPSS), and Sense of Mastery (SOM). Data were analysed using SPSS for Windows 22.0 (SPSS Inc., 2013).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the local Florence Ethics Committee (acceptance protocol number 2010/0008185 Ref. 19/10 and 2011/0027621 Ref. 70/11.) and was conducted in accordance with introduced and authorized amendments as well as with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm). The participants were informed by the investigator on the purposes and objectives of the research and signed specific informed consent to the study and to the processing of personal data. An information note was attached to the consent, which clarified the voluntary participation in the research and the possibility of withdrawing from it at any time. The information also specified that the interview and that the data collected would be analyzed and disclosed in a strictly anonymous form.

Results

The descriptive and comparison between the female oncological group and the control group (One Way Anova) for psychosocial variables was showed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Psychosocial Variables (One way ANOVA).

| Oncological group n= 236 | Control group n= 232 | F | p | |||||

| Mean | Std. deviation | Std.Error | Mean | Std. deviation | Std.Error | |||

| Cumulative effect early life events | 1.14 | 1.08 | .07 | .60 | .85 | .07 | 63.26 | <.01 |

| Cumulative effect recent life events | .50 | .69 | .04 | .27 | .5 | .03 | 22.09 | <.01 |

| Anxiety scale HADS | 8.17 | 3.64 | .27 | 8.09 | 3.56 | .32 | 8.31 | <.01 |

| Depression scale HADS | 7.60 | 3.23 | .24 | 6.51 | 2.88 | .26 | 49.8 | <.01 |

| Beck Depression Inventory BDI | 6.58 | 6.76 | .44 | 3.81 | 7.16 | .57 | 38.30 | <.01 |

| Friends social perceived support | 6.11 | 1.47 | .13 | 5.86 | 1.69 | .16 | 2.84 | <.01 |

| Family social perceived support | 6.42 | 1.21 | .11 | 6.47 | 1.04 | .10 | 5.47 | <.01 |

| Others social perceived support | 6.58 | .99 | .09 | 6.55 | .96 | .09 | 3.51 | <.01 |

| Sense Of Mastery | 31.82 | 8.11 | .53 | 33.76 | 7.8 | .63 | 19.7 | <.01 |

The mean score of stressful events (Early Life Events m= 1.14 and Recent Life Events m= 0.50), affective symptoms when assessed by HADS (anxiety m= 8.17 and depression m=7.60), and BDI m= 6.58 was higher in the clinical group, while sense of mastery m= 31.82 and Perceived Family Social Support m=6.42 were lower than control group. All comparison above mentioned were statistically significant (p <.01).

A discriminant analysis was conducted to assess whether the nine predictors could allow to distinguish between the subject who belonged to the clinical group and those who did not. —the predictors were: Cumulative effect Early Life Events, Cumulative effect Recent Life Events, Anxiety Scale HADS, Depression Scale HADS, Beck Depression Inventory BDI, Friends Social Perceived Support, Family Social Perceived Support, Others Social Perceived Support, Sense of Mastery. Wilks’ lambda was significant: Ʌ = .680, X2 = 109.73, p < .001, and this indicates that the model including these nine variables was able to significantly discriminate between the two groups.

Figure 2 shows the standardized function coefficients, which suggest that Depression scale HADS, Anxiety scale HADS, the Cumulative Effect of Recent Life Events and the Cumulative Effect of Early Life Events (respectively 0.64, 0.54, 0.53, 0.52) contribute the most to distinguish between those who belonged to clinical group from those who did not, using these predictors. The Standardized Function Coefficients of those variables of the model respect the cut-off of .30. So, scores obtained by variables above considered qualify their as valid marker of the model.

Figure 2.

Standardized function coefficients of the model

Note. Standardized Discriminant Coefficients of the final discriminant function that separates out the Female cancer group (n = 236) from the Control group (n= 232). Standardized Discriminant Coefficients are the equivalent of beta weights in regression. Good predictors tend to have large values of the Standardized Discriminant Coefficients. In particular valid predictors (named Adequate Variables) are variables showing a Standardized Discriminant Coefficient higher than |.30|. In the present model Adequate Variables are: Cumulative Effect of Recent Life Events, Anxiety scale HADS, Depression Scale HADS, and Cumulative Effect of Early Life Events (here Grey Columns represent the Standardized Discriminant Coefficients of the Adequate Variables in the model).

The classification results show that the model correctly predicts 69.4 % of those who belonged to the clinical group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Classification of those who belonged to the clinical group in model

Note. The validity of Discriminant Analysis is tested by contrasting the power to discriminate provided by the Discriminant Model with a chance classification: reclassification of the Female Cancer Group (n= 236) and of the Control Group (n= 232) obtained with the Discriminant Model. On the left we have reported the “improvement over chance criterion” (IOCC), showing that more that 80% of the Female Cancer patients are correctly reclassified by the Discriminant Function (gray bar, left). On the right re-classification is obtained with the cross-validation procedure. It is described as a ‘jack-knife’ classification, in that it successively classifies all cases but one to develop a discriminant function and then categorizes the case that was left out. This process is repeated with each case left out in turn. This cross validation produces a more reliable function. Here the difference between the results obtained with the two methods is minimal, as more than 79% of the Female Cancer patients are correctly reclassified with cross-validation (gray bar, left). Both procedures detect a valid discriminative power for the Model

Table 2 presents the correlations between the study variables and discriminant function. Stressful Early Life Events, Stressful Recent life events, Anxiety and Depression scale assessed by HADS contributed strongly to the discriminant function because their r-value exceeds the cut-off of .30. In fact, their value was respectively 0.41, 0.50, 0.33, 0.59. Those scores allow us to consider those variables as adequate markers of the model tested.

Table 2.

Correlations between variables and discriminant function product by the model comparing a female cancer group n= 236 with a control group n= 232.

| Dimension assessed | Correlation score |

| Sense of mastery | .149 |

| Anxiety scale HADS | .331 |

| Depression scale HADS | .590 |

| Beck Depression Inventory BDI | -.102 |

| Friends social perceived Support | .088 |

| Family social perceived Support | -.028 |

| Others social perceived Support | .071 |

| Cumulative effect recent life events | .413 |

| Cumulative effect early life events | .502 |

Note. Person’s Correlations between the Discriminant Model’s Variables and the Standardized Canonical Discriminant Function (structure matrix). In general, 0.30 is considered to be the cut-off between relevant and less relevant variables.

Discussion and Conclusion

Although the present research is not an epidemiologic study of psychosocial factors in oncology, some of the data are useful in terms of understanding discriminant factors in female cancer. In accordance with previous findings (24), almost all the oncological participants in the present study reported more psychosocial needs and stressful events (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 17, 18, 38) than healthy participants.

Previous empirical findings have shown that stressful life events and psychosocial problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, and low social support), predispose oncological patients to psychological distress and negative outcomes (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 38). In the present study, the discriminant analysis was performed to verify the hypothesis that the variables in the model can be consider an adequate marker for a discriminant function; thus, the plausibility of the postulated discrimination among groups was tested. The model was able to correctly allocate around 69.4 % of the subjects to the groups. Markers that are more adequate were especially those represented by stressful events and depressive-anxious symptomatology. This result is in line with the findings from previous studies that underline high level of psychological distress in clinical sample (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 39).

Hence, these results indicate that several components, such as adverse life events and psychosocial variables, can explain the psychological condition of oncological patients at incidence time. Even if the clinical group obtained significant lower scores relative to the control group, the results seem to suggest that this dimension might be less important in discriminating between oncological patients and healthy controls relative to the other variables assessed by the current study. There are some possible explanations for this result.

First, a suppression effect might explain this finding as cancer patients’ perception of social support and depressive symptoms are strongly inter-related (40). Previous studies (41) suggested that the most important source of support for cancer patients is the family. However, caring for a family member with cancer poses significant challenges, with considerable potential psychosocial consequences for the caregiver, especially in advanced cancer. On the one hand, this might explain the lower scores obtained by cancer patients on the measure used to assess social support. On the other hand, future studies should focus their attention on different sources of support to further clarify the association between patients’ s perception of social support and depressive symptoms.

Moreover, whereas previous studies suggest that social support from significant others work as a buffer against reaction to stressful events, less studied is the potential effect of these events on the perception of social support itself. It is not possible to rule out the possibility that stressful live events have a negative impact on the perception of support itself.

Some limitations of the present study must be acknowledged. The retrospective and cross-sectional design of the study obviously introduces the possibility of a recall bias caused by cancer diagnosis or memory distortion, as patients re-evaluate their lives based on their health state and might selectively recall their experience before the diagnosis.

For these reasons, only objectively verifiable early events were assessed as loss and separation.

A larger sample and a more detailed investigation are therefore necessary to confirm the psychological discriminant factors on female cancer and to evaluate other factors that may modulate the response to traumatic childhood events (e.g., temperament, attachment, and parental style).

Our results are congruent with the clinical observations of several studies (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 46), confirming the need to consider specific psychosocial needs among female cancer patients.

Identifying patients at particularly high risk for psychological adjustment difficulties represents an important step toward designing interventions tailored for the difficulties and circumstances of different groups (47, 3, 1, 5, 26).

Therefore, our results point out the importance of an accurate assessment procedure of psychosocial factors in oncology. Specifically, they suggest the consideration on assessment procedure of four dimensions: stressful events (Cumulative Early life events, Cumulative Recent Events Trigger Events), Anxiety and Depression assessed by HADS (29). Our findings point out also the relevance to manage the above-cited dimensions with proper interventions. Women affected by female cancer with an history of Stressful Early and Recent life events and high level of anxiety and depression could positively benefit from a psychotherapy treatment.

Conflicts of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Senf B, Brandt H, Dignass A, Kleinschmidt R, Kaiser J. Correction to: Psychosocial distress in acute cancer patients assessed with an expert rating scale. Sup Ca Can. 2020 May;28(5):24–33. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05305-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betchen M, Grunberg VA, Gringlas M, Cardonick E. Being a mother after a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy: Maternal psychosocial functioning and child cognitive development and behavior. Psychoonc. 2020;13(29):1148–1155. doi: 10.1002/pon.5390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Meglio A, Michiels S, Jones LW, et al. Changes in weight, physical and psychosocial patient-reported outcomes among obese women receiving treatment for early-stage breast cancer: A nationwide clinical study. Breast. 2020 Apr 11;(52):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aamir D, Waseem Y, Patel MS. Psychosocial implications in breast cancer. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020 Feb;70(2):386. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.48474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sah GS. Psychosocial and Functional Distress of Cancer Patients in A Tertiary Care Hospital: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. Jou Nep Medi Assoc. 2019;57(218):252–258. doi: 10.31729/jnma.4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kugbey N, Oppong Asante K, Meyer-Weitz A. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life among women living with breast cancer in Ghana: mediating roles of social support and religiosity. Sup Ca Can. 2020 Jun;28(6):2581–2588. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho E, Docherty SL. Beyond Resilience: A Concept Analysis of Human Flourishing in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Adv Nur Sci. 2020;43(2):172–189. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsaras K, Papathanasiou IV, Mitsi D, et al. Assessment of Depression and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018 Jun 25;19(6):1661–1669. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.6.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faravelli C, Miraglia Raineri A, Fioravanti G, Pietrini F, Alterini R, Rotella F. Childhood adverse events in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a discriminant function. Drugs Cell Ther Hem. 2015;3(2):92–99. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faravelli C, Fioravanti G, Casale S, et al. Early life events and gynaecological cancer: A pilot study. Psycho psychos. 2011;81(1):56. doi: 10.1159/000329176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sievert LL, Jaff N, Woods NF. Stress and midlife women’s health. Wome Midl Hea. 2018, 16;4(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s40695-018-0034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohrenwend BS, Krasnoff L, Askenasy AR, Dohrenwend BP. The Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview Life Events Scale. In: Goldberger L, Breznitz S, editors. Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects. New York: Free Press; 1982. pp. 332–63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seiler A, Jenewein J. Resilience in Cancer Patients. Front Psychiatry. 2019;5(10):208. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almigbal TH, Almutairi KM, Fu JB, et al. Assessment of psychological distress among cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy in Saudi Arabia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019, 20;12:691–700. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S209896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psych bul. 1985;98(2):310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP. Life stress and illness Formulation of the issues. In: Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP, editors. Stressful life events and their contexts. New York: Prodist; 1981. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozdemir D, Tas Arslan F. An investigation of the relationship between social support and coping with stress in women with breast cancer. Psychooncol. 2018;27(9):2214–2219. doi: 10.1002/pon.4798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeung NCY, Lu Q. Perceived Stress as a Mediator Between Social Support and Posttraumatic Growth Among Chinese American Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(1):53–61. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thoits PA. Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical problems in studying social support as a buffer against life stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1982;(23):145–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osuji PN, Onu JU. Feeding behaviors among incident cases of schizophrenia in a psychiatric hospital: Association with dimensions of psychopathology and social support. Clin nutr ESP. 2019;34:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price M, Lancaster CL, Gros DF, Legrand AC, Van Stolk-Cooke K, Acierno R. An examination of social support and PTSD treatment response during prolonged exposure. Psychiat. 2018;81(3):258–270. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2017.1402569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Oostrom MA, Tijhuis MA, De Haes JC, Tempelaar R, Kromhout D. A measurement of social support in epidemiological research: the social experiences checklist tested in a general population in The Netherlands. Jou epide comm heal. 1995;49(5):518–524. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.5.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waliston BS, Alagna SW, DeVellis BM, DeVelfis RF. Reviews. Social support and physical health. Helth Psychol. 1983;2:367. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat clin pract Onco. 2008;5(8):466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansourabadi A, Moogooei M, Nozari S. Evaluation of Distress and Stress in Cancer Patients in AMIR Oncology Hospital in Shiraz. Irania Jour Pedi Hem Onc. 2014;4(4):131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpenter KM, Fowler JM, Maxwell GL, Andersen BL. Direct and buffering effects of social support among gynecologic cancer survivors. Ann Beh Med. 2010;39(1):79–90. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9160-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faravelli C, Bartolozzi D, Cimminiello L, et al. The Florence psychiatric interview. Inter Jour Meth Psychi Rese. 2001;10(4):157–171. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. Journal of health and social behaviour. 1978:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psyc scan. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Jour of pers assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonacchi A, Miccinesi G, Galli S, Chiesi F, Martire M, Guazzini M, Toccafondi A, Fazzi L, Balbo V, Vanni D, Rosselli M, Primi C. The Dimensionality of Antonovsky’s Sense of Coherence Scales. An Investigation with Italian Samples. TM. 2012;19(2):115–134. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. Jou psychos res. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costantini M, Musso M, Viterbori P, Bonci F, Del Mastro L, Garrone O, Venturini M, Morasso G. Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: validity of the Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Supp Care Canc. 1999;7(3):121–127. doi: 10.1007/s005200050241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Fabio A, Busoni L. Misurare il supporto sociale percepito: Proprietà psicometriche della Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) in un campione di studenti universitari. Risorsa Uomo. Riv Psic Lav Organiz. 2008;14:339–350. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sica C, Ghisi M. The Italian versions of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Beck Depression Inventory-II: Psychometric properties and discriminant power. In: Lange M. A, editor. Leading-edge psychological tests and testing research. Nova Science Publishers; 2007. pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leech NL, Barrett KC, Morgan GA. In SPSS for intermediate statistics: Use and interpretation. Psycho Press; 2007. Logistic Regression and Discriminant Analysis; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen CC, David AS, Nunnerley H, et al. Adverse life events and breast cancer: case-control study. Bmj. 1995;311(7019):1527–1530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7019.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGregor BA, Antoni MH. Psychological intervention and health outcomes among Women treated for Breast Cancer: a review of stress pathways and biological mediators. Brain beh immu. 2009;23(2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hann D, Baker F, Denniston M, et al. The influence of social support on depressive symptoms in cancer patients: age and gender differences. Jour of psych rese. 2002;52(5):279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slevin ML, Nichols SE, Downer SM, Wilson P, Lister TA, Arnott S, Cody M. Emotional support for cancer patients: what do patients really want? Brit jou of canc. 1996;74(8):1275–1279. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neuling SJ, Winefield H. R. Social support and recovery after surgery for breast cancer: frequency and correlates of supportive behaviours by family, friends and surgeon. Soc scie & medi. 1988;27(4):385–392. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trask PC, Paterson AG, Trask CL, Bares CB, Birt J, Maan C. Parent and adolescent adjustment to pediatric cancer: Associations with coping, social support, and family function. Jour of ped oncol nurs. 2003;20(1):36–47. doi: 10.1053/jpon.2003.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pehlivan S, Ovayolu O, Ovayolu N, Sevinc A, Camci C. Relationship between hopelessness, loneliness, and perceived social support from family in Turkish patients with cancer. Supp Car Canc. 2012;20(4):733–739. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazak A. E, Meadows A. T. Families of young adolescents who have survived cancer: Social-emotional adjustment, adaptability, and social support. Jour of Pedia Psycho. 1989;14(2):175–191. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, Zuckerman E, et al. Social support as a buffer to the psychological impact of stressful life events in Women with Breast Cancer. Canc. 2001;91(2):443–454. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010115)91:2<443::aid-cncr1020>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trevino KM, Stern A, Prigerson HG. Adapting psychosocial interventions for older adults with cancer: A case example of Managing Anxiety from Cancer (MAC) J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;3 doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.03.012. S1879-4068(20)30152-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]