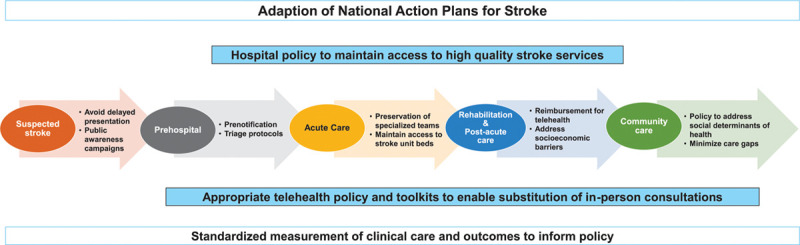

Advances in stroke care policy during 2020 were largely influenced by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (over 765 articles in web-of-science, 57 in the journal Stroke, 17 with keyword policy). People with COVID-19 have a 1.5% increased chance of stroke1; those with stroke and COVID-19 have worse outcomes compared with those without a history of stroke.2,3 It is essential to prevent transmission to patients with stroke and maintain standards of stroke care to avoid unnecessary death and disability.4,5 Several regions released guidance early in the pandemic and may still be responding.6–9 As examples of rapidly evolving policy, the current European stroke action plan was adapted to cover COVID-19,10 and the Canadian stroke best practice recommendations were modified to provide a virtual (telestroke) health care management toolkit for individuals with stroke.11 In this article, we summarize the main themes that emerged based on the different phases of care (Figure) and provide future considerations for policies that could protect the integrity of evidence-based stroke care. Essential to realizing the impact of new policy is having standardized data to assess whether the intended outcomes have been achieved.

Figure.

Policies to maintain the integrity of stroke care during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Public Awareness and Acute Stroke

There were concerns among the stroke community that people with suspected stroke have been avoiding the hospital. Delays in arriving to hospital, coupled with new infection control screening procedures, have meant some people with stroke miss out on time critical treatments.6 Emergency medical services were to have protocols in place for safe and timely transport of suspected pandemic-infected patients and prenotify hospitals to launch code stroke.11 Emergency department triage protocols and workflows changed including overcoming logistical issues for imaging and telemedicine access.11 Examples also included modifying standard poststroke treatment monitoring procedures to reduce the frequency of patient assessments that require repeated donning and doffing of personal protection equipment over short intervals of time.12 The impact of these protocol changes remains unclear.

To increase capacity for the management of patients with COVID-19, hospitals repurposed wards and redeployed staff from different disciplines or specialties.7 To minimize the impacts on care quality, acute stroke care protocols were adapted so that hospital staff unfamiliar with stroke care required minimal training.13 In countries where stroke unit staffing and beds were protected, the quality of stroke care remained unchanged during the pandemic.14 Therefore, hospital executives have been encouraged to maintain and protect the integrity of stroke services to avoid unnecessary disability, complications, or deaths after stroke.15

Rehabilitation and Community-Based Care

The shifts in acute care bed availability and staffing had a cascading effect on inpatient rehabilitation, the transition home after stroke, outpatient rehabilitation, and specialty care follow-up. During periods of pandemic surge when the demands for acute care beds were increased, several regions reported fewer rehabilitation admissions, and shorter lengths of inpatient stays for patients who receive rehabilitation.16 This had implications for being able to adequately assess and treat patients, adhere to stroke rehabilitation guidelines, secure equipment, arrange follow-up appointments, and train family.17,18 Caregivers for patients with stroke have reported being unsure of prognosis and being unprepared for discharge. Visitor restriction policies and lack of video conferencing to connect patients and therapists with family caregivers were major barriers to their readiness to continue care at home.19 Some countries approved new or emergency policies to provide additional funds to informal caregivers taking on additional responsibilities due to the decreased access to home and community-based services. It is unclear if these policies have improved the circumstances for caregivers of stroke survivors.

Pivoting to Virtual Stroke Care

Safety and effectiveness of adapted models of care is uncertain, especially regarding telehealth for rehabilitation services. Funding arrangements, protocols, and policy to support such initiatives were lacking or imperfect.20 Many nations with telehealth infrastructure and governing laws for cybersecurity had not fully deployed reimbursement policies for providers, particularly for outpatient specialty or rehabilitation services.21 In the United States and Belgium, laws changed quickly and reimbursement for outpatient rehabilitation provided by therapists was made possible. There were steep learning curves for rehabilitation therapists who have not used telehealth as part of their standard practice for stroke. For most nations, it remains unclear whether patients requiring rehabilitation were adequately reached and treated.

Complicating use of telehealth was digital equity for stroke survivors. Even in well-resourced regions, there were marked disparities in access to telehealth after stroke associated with individuals’ lower incomes and economic instability, or being from underserved geographies or historically marginalized communities including those with disabilities.22

Reducing Inequities, Adapting Actions Plans, and Measuring Impact

Beyond the health disparities known in stroke incidence and outcomes further exacerbated by the pandemic, more upstream policies need higher prioritization.23 It is imperative that the stroke community contribute to data-driven policy solutions that eliminate inequities in access to healthy food, stable housing, safe neighborhoods, high quality education and health care, and employment with a livable wage. Establishing policies that address these social determinants of health is essential.24 In the field of stroke, national scientific societies, stroke support organizations, and governmental agencies need to be engaged in adapting action plans to include virtual approaches to care, and creating educational resources for clinicians and survivors/caregivers.10 It is essential that we ensure accessible and trustworthy information and support for survivors and caregivers particularly when direct access to health care professionals is constrained or limited.10

Conclusions

The unintended consequences of COVID-19 and the implications of health system and public health policy changes to deal with the pandemic for stroke are yet to be fully determined. The stroke community needs to work together to address these new challenges and measure the impact. We encourage researchers to generate evidence to support policy and planning for stroke to ensure patients are not further disadvantaged. We need to be able to learn from these events in how to respond and make appropriate and timely policies.

Sources of Funding

No specific funding to complete this article was obtained. Professor Cadilhac acknowledges research fellowship support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia, #1154273).

Disclosures

None.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- COVID-19

- coronavirus disease 2019

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the editors or of the American Heart Association.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 2179.

References

- 1.Merkler AE, Parikh NS, Mir S, Gupta A, Kamel H, Lin E, Lantos J, Schenck EJ, Goyal P, Bruce SS, et al. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with covid-19 versus patients with influenza [preprint]. medRxiv. 2020. Preprint posted online May 21, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.18.20105494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Payus AO, Liew Sat Lin C, Mohd Noh M, Jeffree MS, Ali RA. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the nervous system: a review of the literature on neurological involvement in novel coronavirus disease-(COVID-19). Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2020;20:283–292. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2020.4860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kummer BR, Klang E, Stein LK, Dhamoon MS, Jetté N. History of stroke is independently associated with in-hospital death in patients with COVID-19. Stroke. 2020;51:3112–3114. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L, Sun W, Wang Y, Wang X, Liu Y, Zhao S, Long D, Chen L, Yu L. Clinical course and mortality of stroke patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Stroke. 2020;51:2674–2682. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguiar de Sousa D, van der Worp HB, Caso V, Cordonnier C, Strbian D, Ntaios G, Schellinger PD, Sandset EC, Organisation ES. Maintaining stroke care in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from an international survey of stroke professionals and practice recommendations from the European Stroke Organisation. Eur Stroke J. 2020;5:230–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markus HS, Brainin M. COVID-19 and stroke-A global World Stroke Organization perspective. Int J Stroke. 2020;15:361–364. doi: 10.1177/1747493020923472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wira CR, Goyal M, Southerland AM, Sheth KN, McNair ND, Khosravani H, Leonard A, Panagos P; AHA/ASA Stroke Council Science Subcommittees: Emergency Neurovascular Care (ENCC), Telestroke and the Neurovascular Intervention Committees; and on behalf of the Stroke Nursing Science Subcommittee of the AHA/ASA Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing Council. Pandemic guidance for stroke centers aiding COVID-19 treatment teams. Stroke. 2020;51:2587–2592. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sylaja PN, Srivastava MVP, Shah S, Bhatia R, Khurana D, Sharma A, Pandian JD, Kalia K, Sarmah D, Nair SS, et al. The SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and challenges in stroke care in India. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1473:3–10. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AHA/ASA Stroke Council Leadership. Temporary emergency guidance to US stroke centers during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: on behalf of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council Leadership. Stroke. 2020;51:1910–1912. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen H, Pezzella FR; Action Plan for Stroke in Europe Implementation Steering Committee. Implementation of the Stroke Action Plan for Europe 2018–2030 during coronavirus disease-2019. Curr Opin Neurol. 2021;34:55–60. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blacquiere D, Gubitz G, Yu AY, Wein T, McGuff R, Pollard J, Smith EE, Mountain A, Lindsay P. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations 7th Edition: Virtual Healthcare (Telestroke) Implementation Toolkit. 2020;34Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/1-stroke-best-practices/csbpr7-virtualcaretools-13may2020 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gioia LC, Poppe AY, Laroche R, Dacier-Falque T, Sévigny I, Daneault N, Deschaintre Y, Jacquin G, Stapf C, Odier C. Streamlined poststroke treatment order sets during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: simplifying while not compromising care. Stroke. 2020;51:3115–3118. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Silva DA, Fan TI, Shamala D, Thilarajah O. A protocol for acute stroke unit care during the COVID-19 pandemic: acute stroke unit care during COVID-19. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29:105009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudilosso S, Laredo C, Vera V, Vargas M, Renú A, Llull L, Obach V, Amaro S, Urra X, Torres F, et al. Acute stroke care is at risk in the era of COVID-19: experience at a comprehensive stroke center in Barcelona. Stroke. 2020;51:1991–1995. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coote S, Cadilhac DA, O’Brien E, Middleton S; Acute Stroke Nurses Education Network (ASNEN) Steering Committee. Letter to the Editor regarding: Critical considerations for stroke management during COVID-19 pandemic in response to Inglis et al., Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29(9): 1263-1267. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29:1895–1896. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.09.925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prvu Bettger J, Thoumi A, Marquevich V, De Groote W, Rizzo Battistella L, Imamura M, Delgado Ramos V, Wang N, Dreinhoefer KE, Mangar A, et al. COVID-19: maintaining essential rehabilitation services across the care continuum. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindsay P, Furie KL, Davis SM, Donnan GA, Norrving B. World Stroke Organization global stroke services guidelines and action plan. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(Suppl A100):4–13. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B, Cherney LR, Cramer SC, Deruyter F, Eng JJ, Fisher B, Harvey RL, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47:e98–e169. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutter-Leve R, Passint E, Ness D, Rindflesch A. The caregiver experience after stroke in a COVID-19 environment: a qualitative study in inpatient rehabilitation. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2021;45:14–20. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bersano A, Kraemer M, Touzé E, Weber R, Alamowitch S, Sibon I, Pantoni L. Stroke care during the COVID-19 pandemic: experience from three large European countries. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1794–1800. doi: 10.1111/ene.14375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein BC, Busis NA. COVID-19 is catalyzing the adoption of teleneurology. Neurology. 2020;94:903–904. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al Rifai M, Shapiro MD, Sayani S, Gulati M, Levine G, Rodriguez F, Mahtta D, Khera A, Petersen LA, Virani SS. Racial and geographic disparities in internet use in the United States among patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2020;134:146–147. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, Mills A, Odom TM, Rodriguez CJ, Rodriguez F, et al. ; American Heart Association. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e454–e468. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marmot M. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ. 2020;368:m693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]