Study Design:

This was a cross-sectional study.

Objective:

The objective of this study is to report the impact of COVID-19 on spine surgery fellow education and readiness for practice.

Summary of Background Data:

COVID-19 has emerged as one of the most devastating global health crises of our time. To minimize transmission risk and to ensure availability of health resources, many hospitals have cancelled elective surgeries. There may be unintended consequences of this decision on the education and preparedness of current surgical trainees.

Materials and Methods:

A multidimensional survey was created and distributed to all current AO Spine fellows and fellowship directors across the United States and Canada.

Results:

Forty-five spine surgery fellows and 25 fellowship directors completed the survey. 62.2% of fellows reported >50% decrease in overall case volume since cancellation of elective surgeries. Mean hours worked per week decreased by 56.2%. Fellows reported completing a mean of 188.4±64.8 cases before the COVID-19 crisis and 84.1% expect at least an 11%–25% reduction in case volume compared with previous spine fellows. In all, 95.5% of fellows did not expect COVID-19 to impact their ability to complete fellowship. Only 2 directors were concerned about their fellows successfully completing fellowship; however, 32% of directors reported hearing concerns regarding preparedness from their fellows and 25% of fellows were concerned about job opportunities.

Conclusions:

COVID-19 has universally impacted work hours and case volume for spine surgery fellows set to complete fellowship in the middle of 2020. Nevertheless, spine surgery fellows generally feel ready to enter practice and are supported by the confidence of their fellowship directors. The survey highlights a number of opportunities for improvement and innovation in the future training of spine surgeons.

Level of Evidence:

Level III.

Key Words: spine surgery, fellowship, COVID-19, education, coronavirus, orthopaedic surgery, neurological surgery

The novel coronavirus known as COVID-19 has rapidly emerged as one of the most disastrous global health crises of our time.1,2 Patients infected with COVID-19 have placed an enormous strain on health care systems across the world.3 Meeting these demands in severely affected regions has proven challenging for hospitals and health care workers.4 To address the increased risk to patients and health care workers, many United States hospitals and surgery centers postponed all elective surgeries in March 2020.5

Despite the suspension of elective surgery, orthopedic,6 neurosurgical,7 and spine surgery8 teams across the United States have continued to provide urgent and emergent services. Although numerous editorials, letters, and society-level guidelines have been published to address the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on spine surgery care, little is known about the impact of the pandemic on the spine fellow experience and education.8–10

Over the past several decades, fellowship training has become increasingly popular among neurosurgeons11 and essentially necessary for orthopedic surgeons12 intent on practicing spine surgery. For orthopedic surgeons, in particular, fellowship may provide the majority of operative spine experience during training, with a goal of completing 250+ cases in one year.13–15 Given the importance of the fellowship experience for spine surgery education and the universal effect of COVID-19 on reducing elective spine surgery volume, we sought to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on the 2019–2020 spine surgery fellowship training and preparedness for practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey Design and Content

A working group comprised of board-certified spine surgeons and trainees developed the questionnaire for current spine fellows during the 2019–2020 academic year and fellowship directors. Question selection was based on the Delphi technique16 to achieve consensus through several rounds of expert review before finalization. Two variations of the survey were developed to target both current spine fellows and fellowship directors.

The survey was constructed using SurveyMonkey (San Mateo, CA). The scope of the survey included location of fellowship, residency training, time frame as to when elective surgeries were cancelled, impact on practice, impact on fellowship education, and impact on job opportunities. A Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1, not concerned; 5, extremely concerned) was used to measure impact responses. US regions of practice in the survey were defined by the United States Census Bureau.17 The study was submitted for Institutional Review Board approval and deemed exempt.

Survey Distribution

Both the 40-item fellows survey and the 44-item fellowship directors survey were presented in English and distributed via email to AO Spine North America fellows (n=103) and fellowships directors (n=41). The list of fellows and directors was provided by AO Spine North America. The survey recipients had 9 days to complete the survey (April 28, 2020 to May 6, 2020). Respondents were informed that their participation was voluntary, that they could end their participation at any time, and that all data would be kept confidential (ie, only nonidentifiable aggregate data would be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals, websites, and social media).

Statistical Analyses

Percentages and means were calculated for count and rank-order data, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed to assess for differences in count data using the Fisher exact and χ2 tests. Differences in continuous variables between groups were assessed using the student t test. All statistical analyses were performed with XLStat (Addinsoft, Paris, France). A significant difference was determined for P<0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 45 spine surgery fellows and 25 fellowship directors responded to the survey with response rates of 43.7% and 61.0%, respectively. Respondents represented 18 US states and Canadian provinces. Most fellows had completed residency in orthopedic surgery (35/45, 77.8%) versus neurological surgery (10/45, 22.2%). The majority of fellows were training in the Northeast, Midwest, and West (30/45, 66.7%) and the majority of fellowship directors were from the West and Midwest (15/25, 60.0%). 45% of fellows (18/45) and 40% of fellowship directors (10/25) represented programs located in large cities with >1 million people. 21% of all respondents reported surgeons in their program who tested positive for COVID-19 (15/70) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Survey Respondent Demographics

| Fellows | # | % | Fellowship Directors | #/Mean | %/SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residency education | Residency education | ||||

| Neurological surgery | 10 | 22.2 | Neurological surgery | 5 | 20.0 |

| Orthopedic surgery | 35 | 77.8 | Orthopedic surgery | 20 | 80.0 |

| Fellowship region | Fellowship region | ||||

| Northeast | 10 | 22.2 | Northeast | 2 | 8.0 |

| Midwest | 10 | 22.2 | Midwest | 6 | 24.0 |

| South | 7 | 15.6 | South | 4 | 16.0 |

| West | 10 | 22.2 | West | 9 | 36.0 |

| Canada | 6 | 13.3 | Canada | 4 | 16.0 |

| Other | 2 | 4.4 | Other | 0 | 0.0 |

| Fellowship setting population* | Fellowship setting population‡ | ||||

| <100,000 | 2 | 5.0 | <100,000 | 1 | 4.17 |

| 100,000–500,000 | 8 | 20.0 | 100,000–500,000 | 7 | 29.17 |

| 500,000–1,000,000 | 12 | 30.0 | 500,000–1,000,000 | 6 | 25.0 |

| 1,000,000–2,000,000 | 2 | 5.0 | 1,000,000–2,000,000 | 2 | 8.3 |

| >2,000,000 | 16 | 40.0 | >2,000,000 | 8 | 33.3 |

| Years in surgical practices | 17.0 | 7.2 | |||

| Years as fellowship director | 9.5 | 7.8 | |||

| Programs with staff testing positive for COVID† | Programs with Staff Testing Positive for COVID† | ||||

| Attending staff | 6 | 13.6 | Attending staff | 1 | 4.0 |

| Fellows | 1 | 2.3 | Fellows | 0 | 0.0 |

| Residents | 4 | 9.1 | Residents | 3 | 12.0 |

| Ancillary staff | 9 | 20.5 | Ancillary staff | 3 | 12.0 |

| None | 30 | 68.2 | None | 19 | 76.0 |

| Total respondents | 45 | 100.0 | 25 | 100.0 |

COVID-19 Impact and Response

One-half of fellowship programs enacted COVID-19 precautions before March 15 as reported by fellows (23/45, 51.1%) and directors (13/24, 54.2%). All fellows and directors reported cancellation of elective cases due to COVID-19. Most fellows (28/45, 62.2%) reported a decrease in case volume of >50%. Before the suspension of elective spine surgeries, fellows reported working an average of 64.8±14.6 hours weekly. Subsequently, fellows reported working and average of 28.4±17.7 hours weekly, representing a 36.4±16.2 hour (56.2%) decrease (P<0.0001). Nearly a quarter of fellows (11/45, 24.4%) reported being redeployed to non–spine-related patient care roles. Most fellows (38/44, 86.4%) were satisfied with the current precautions with unique OR guidelines for COVID-19 patients (41/44, 93.2%), extended OR turnover time (28/44, 63.6%), and limiting number of learners in the OR (28/44, 63.6%) being the most common. However, some fellows have considered precautions that have not been implemented (4/44, 9.1%) and 22.7% believe that their safety had been compromised during the COVID-19 crisis (10/44). A majority of fellows (26/44, 59.1%) discussed COVID-19 precautions with their fellowship directors and most reported that their programs or hospitals have provided resources to cope with stress, including reducing the number of in-house work hour requirements (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

COVID-19 Response

| Fellows (n=45) | #/Mean | %/SD | Fellowship Directors (n=25) | #/Mean | %/SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start date of COVID precautions | Start date of COVID precautions | ||||

| Before March 1st | 2 | 4.4 | Before March 1st | 1 | 4.0 |

| March 1–14 | 21 | 46.7 | March 1–14 | 12 | 48.0 |

| March 15–31 | 21 | 46.7 | March 15–31 | 12 | 48.0 |

| April 1st to present | 1 | 2.2 | April 1st to Present | 0 | 0.0 |

| No changes made | 0 | 0.0 | No changes made | 0 | 0.0 |

| Elective cases cancelled | 45 | 100.0 | Elective cases cancelled | 25 | 0.0 |

| Decrease in overall institution case volume | Decrease in overall institution case volume | ||||

| 0–25% | 2 | 4.4 | 0–25% | 1 | 4.0 |

| 26%–50% | 15 | 33.3 | 26%–50% | 3 | 12.0 |

| 51%–75% | 12 | 26.7 | 51%–75% | 10 | 40.0 |

| >75% | 16 | 35.6 | >75% | 11 | 44.0 |

| Mean hours worked per week before COVID | 64.8 | 14.6 | Mean hours fellows worked per week before COVID | 66.4 | 10.5 |

| Mean hours worked per week during COVID | 28.4 | 17.7 | Mean hours fellows worked per week during COVID | 28.2 | 15.6 |

| Assisting with non–spine-related care | Fellows assisting with non–spine-related care | ||||

| Yes | 11 | 24.4 | Yes | 3 | 12.0 |

| No | 34 | 75.6 | No | 22 | 88.0 |

| Satisfied with current precautions* | Satisfied with current precautions | ||||

| Yes | 38 | 86.4 | Yes | 24 | 96.0 |

| No | 6 | 13.6 | No | 1 | 4.0 |

| Types of precautions taken* | Types of precautions taken | ||||

| OR guidelines for COVID patients | 41 | 93.2 | OR guidelines for COVID patients | 20 | 80.0 |

| N95 for all COVID positive patients | 24 | 54.6 | N95 for all COVID positive patients | 17 | 68.0 |

| N95 for all untested patients | 17 | 38.6 | N95 for all untested patients | 11 | 44.0 |

| Extended OR turnover time | 28 | 63.6 | Extended OR turnover time | 17 | 68.0 |

| Limiting number of learners in cases | 28 | 63.6 | Limiting number of learners in cases | 14 | 56.0 |

| Testing of all patients before OR | 26 | 59.1 | Testing of all patients before OR | 15 | 60.0 |

| Other | 1 | 2.3 | Other | 3 | 12.0 |

| Additional precautions considered but not implemented* | Additional precautions considered but not implemented | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 9.1 | Yes | 5 | 20.0 |

| No | 40 | 90.9 | No | 20 | 80.0 |

| Has safety been compromised during COVID* | Has safety been compromised during COVID | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 22.7 | Yes | 3 | 12.0 |

| No | 34 | 77.3 | No | 22 | 88.0 |

| Frequency of COVID communication with fellowship director* | Frequency of COVID communication with fellow | ||||

| Bi-weekly | 9 | 20.5 | Bi-weekly | 0 | 0.0 |

| Weekly | 26 | 59.1 | Weekly | 9 | 36.0 |

| Daily | 8 | 18.2 | Daily | 15 | 60.0 |

| Multiple times a day | 1 | 2.3 | Multiple times a day | 1 | 4.0 |

| Provisions to deal with stress* | Provisions to deal with stress | ||||

| Free mental health counseling | 25 | 56.8 | Free mental health counseling | 12 | 48.0 |

| Meditation applications | 15 | 34.1 | Meditation applications | 7 | 28.0 |

| Video conferencing social hours | 20 | 45.5 | Video conferencing social hours | 12 | 48.0 |

| Access to online exercise resources | 14 | 31.8 | Access to online exercise resources | 8 | 32.0 |

| Access to additional online education material | 27 | 61.4 | Access to additional online education material | 19 | 76.0 |

| Free or discounted food | 20 | 45.5 | Free or discounted food | 5 | 20.0 |

| Reduced in-hospital work requirements | 31 | 70.5 | Reduced in-hospital work requirements | 20 | 80.0 |

| Free or discounted child care | 16 | 36.6 | Free or discounted child care | 4 | 16.0 |

| Decision making for nonemergent surgeries | |||||

| Attending decision | 12 | 48.0 | |||

| Service guidelines | 11 | 44.0 | |||

| Hospital/OR guidelines | 20 | 80.0 | |||

| State guidelines | 10 | 40.0 | |||

| National guidelines | 3 | 12.0 | |||

| Standardized scoring system to determine case priority | 9 | 36.0 |

Respondents, n=44.

Fellowship directors reported an overall reduction in case volume with 84% reporting a decrease of >50%. New hospital OR guidelines were the most common reason for cancellation of cases (20/25, 80%) and 36% (9/25) of directors reported using a standardized scoring system to determine case priority. They reported an overall decrease in fellow work hours, from 66.4±10.5 hours to 28.2±15.6 hours per week. This decrease of 38.2±13.7 hours per week was significant (P<0.0001). There was no significant difference in fellow work hours, as reported by fellows and directors, before COVID-19 (P=0.626), during COVID-19 (P=0.963), or in the reported work hour reduction due to COVID-19 (P=0.638). Only 3 fellowship directors (12%) reported that their fellows were taking care of patients outside the scope of spine surgery. Nearly all fellowship directors were satisfied with current precautions (24/25, 96%) and they cited OR guidelines for COVID-19 patients (20/24, 80%), N95s for all COVID-19 positive patients (17/24, 68%), and extended OR turnover times (17/24, 68%) as the most common interventions. Despite these precautions, 20% (5/20) considered additional precautions that had not been implemented and 12% (3/25) felt that their safety had been compromised. Most directors communicated with their fellows daily (15/25, 60%) and reported reduced in-hospital work requirements for fellows (20/25, 80%) (Table 2).

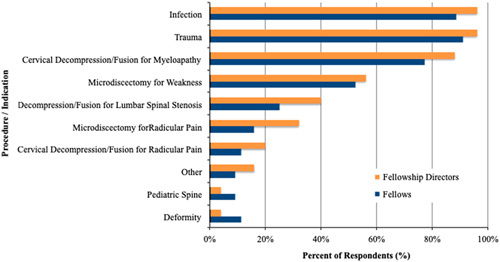

Fellow Case Volume and Case Mix

Before cancellation of elective cases, fellows reported completing 188.4±64.8 spine cases and the fellowship directors reported that their fellows completed 226.4±80.2 cases. This difference in pre-COVID-19 case volume was significant (P=0.037). Fellows reported that the most common spine cases still occurring included trauma (40/44, 90.9%), infection (39/44, 88.6%), and cervical decompression/fusion for myelopathy (34/44, 77.3%) (Fig. 1). Similarly, directors also reported trauma (24/25, 96.0%), infection (24/25, 96.0%), and cervical decompression/fusion for myelopathy (22/25, 88.0%) as the most common procedures occurring during the COVID-19 shutdown. By the end of July 2020, fellows and directors expect fellow case volume to be 82.5% and 81.2% (P=0.945) of the typical case volume for their programs, respectively. When asked directly, most fellows (21/44, 70.5%) and directors (18/25, 72.0%) expected fellow case volume to be reduced by 11%–25% compared with previous years (Table 3).

FIGURE 1.

Case mix of spine cases occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infection, trauma, and cervical decompression/fusion for cervical myelopathy are the most common cases occurring during cessation of elective cases. All numbers are self-reported by spine fellows and fellowship directors.

TABLE 3.

Fellow Case Volume and Mix

| Fellows (n=44) | #/Mean | %/SD | Fellowship Directors (n=25) | #/Mean | %/SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases personally completed before COVID shutdown* | 188.4 | 64.8 | Cases completed by each fellow before COVID shutdown* | 226.4 | 80.2 |

| Cases typically completed by fellows in typical year | 291.8 | 94.5 | Cases typically completed by fellows in typical year | 342.0 | 152.1 |

| Cases expected to completed by July 30, 2020 | 240.7 | 88.3 | Cases expected to completed by July 30, 2020 | 278.6 | 113.6 |

| Estimated percent decrease in yearly case volume vs. last year | Estimated percent decrease in yearly case volume vs. last year | ||||

| 0–10% | 7 | 15.9 | 0–10% | 5 | 28.0 |

| 11%–25% | 31 | 70.5 | 11%–25% | 18 | 72.0 |

| 26%–50% | 6 | 13.6 | 26%–50% | 2 | 8.0 |

| >50% | 0 | 0.0 | >50% | 0 | 0.0 |

| Spine cases still occurring | Spine cases still occurring | ||||

| Trauma | 40 | 90.9 | Trauma | 24 | 96.0 |

| Infection | 39 | 88.6 | Infection | 24 | 96.0 |

| Microdiscectomy for radicular pain | 7 | 15.9 | Microdiscectomy for radicular pain | 8 | 32.0 |

| Microdiscectomy for weakness | 23 | 52.3 | Microdiscectomy for weakness | 14 | 56.0 |

| Cervical decompression/fusion for radicular pain | 5 | 11.4 | Cervical decompression/fusion for radicular pain | 5 | 20.0 |

| Cervical Decompression/fusion for myeloapathy | 34 | 77.3 | Cervical decompression/fusion for myeloapathy | 22 | 88.0 |

| Deformity | 5 | 11.4 | Deformity | 1 | 4.0 |

| Decompression/fusion for lumbar spinal stenosis | 11 | 25.0 | Decompression/fusion for lumbar spinal stenosis | 10 | 40.0 |

| Pediatric spine | 4 | 9.1 | Pediatric spine | 1 | 4.0 |

| Other† | 4 | 9.1 | Other‡ | 4 | 16.0 |

Fellow Preparedness

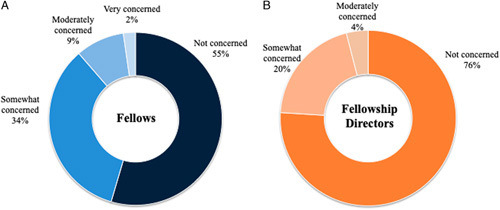

Fellow respondents were generally not concerned about successful completion of fellowship due to COVID-19 (42/44, 95.5%). Before the pandemic, fellows had very low concern regarding their preparedness to enter practice (1.34±0.5, 1=not concerned, 5=extremely concerned). After cancellation of elective cases, fellows experienced a slight increase in their concern (1.59±0.8, 1=not concerned, 5=extremely concerned) although this increase was not statistically significant (0.25±0.3, P=0.068) (Fig. 2). Fellows reported that they would be ready to start practice if elective cases resumed in May (43/44, 97.7%), June (38/44, 86.4%), or July (32/44, 72.7%) and more than 1-quarter of fellows (12/44, 27.3%) voiced concerns to their fellowship director regarding preparedness to start practice (Table 4).

FIGURE 2.

Self-reported concern regarding fellow readiness for practice. A, Fellow self-reported concern regarding personal preparedness to begin practice after fellowship graduation. B, Fellowship director concern regarding their fellows’ readiness to begin practice after fellowship graduation.

TABLE 4.

Fellow Preparedness Versus Fellowship Director Assessment of Preparedness

| Fellow (n=44) | #/Mean | %/SD | Fellowship Director (n=25) | #/Mean | %/SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Will COVID limit fellowship completion? | Will COVID prevent your fellow from successfully completing fellowship? | ||||

| Yes | 2 | 4.6 | Yes | 2.0 | 8.0 |

| No | 42 | 95.5 | No | 23.0 | 92.0 |

| Concern regarding ability to enter practice pre-COVID (1–not concerned, 5–extremely concerned) | 1.34 | 0.48 | Concern regarding ability to enter practice pre-COVID (1–not concerned, 5–extremely concerned) | 1.16 | 0.37 |

| Concern regarding ability to enter practice post-COVID (1–not concerned, 5–extremely concerned) | 1.59 | 0.76 | Concern regarding ability to enter practice post-COVID (1–not concerned, 5–extremely concerned) | 1.28 | 0.54 |

| Prepared to start practice if elective cases resume in: | Fellow prepared to start practice if elective cases resume in: | ||||

| May | 43 | 97.7 | May | 25 | 100.0 |

| June | 38 | 86.4 | June | 24 | 96.0 |

| July | 32 | 72.7 | July | 18 | 72.0 |

| Voiced concern to fellowship director about preparedness | 12 | 27.3 | Fellow voiced concern about preparedness | 8 | 32.0 |

Fellowship directors were not concerned about COVID-19 and its impact on fellows graduating (23/25, 92.0%). Before the pandemic, directors had very low concern (1.16±0.37, 1=not concerned, 5=extremely concerned). After cancellation of elective cases, this concern increased slightly but not significantly (1.28±0.54, Δ0.12±0.17, P=0.367) (Fig. 2). Directors believed that their fellows would be prepared if elective cases resume in May (25/25, 100%), June (24/25, 96.0%), or July (18/25, 72.0%). Directors reported that 32% of their fellows (8/25) voiced concerns regarding their preparedness (Table 4).

Fellows Education and Employment Opportunities

Fellows and fellowship directors reported changes to the current fellow curriculum, with the change to digital/virtual curriculum for didactic education being the most commonly reported by fellows (35/44, 79.6%) and directors (21/25, 84%). For those fellows (33/44, 75.0%) and directors (19/25, 76.0%) who participated in supplemental education not typically offered by their program, additional learning materials offered by their home program (30/33, 90.0% fellows and 19/19, 100% directors) were the most common. A slight majority of fellows (23/44, 52.5%) and directors (13/25, 52.0%) felt connected to their counterparts at other programs during the pandemic. Regarding the impact of COVID-19 on current fellow job opportunities, 25% of all fellows (11/44) were concerned the future of their job. Six fellows (13.6%) reported having no job lined up and 22.7% (10/44) reported having to cancel job interviews due to COVID-19. All in all, 68% of fellowship directors (17/25) believed that their fellows’ training suffered due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Fellow Education and Employment Opportunities

| Fellow (n=44) | # | % | Fellowship Director (n=25) | # | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes to education curriculum | Changes to fellow education curriculum | ||||

| Met less frequently (in-person or virtually) | 17 | 38.6 | Met less frequently (in-person or virtually) | 9 | 36.0 |

| Met more frequently (in-person or virtually) | 18 | 40.9 | Met more frequently (in-person or virtually) | 11 | 44.0 |

| Changed to a digital/virtual curriculum for didactic education | 35 | 79.6 | Changed to a digital/virtual curriculum for didactic education | 21 | 84.0 |

| Already was using a digital/virtual curriculum for didactic education | 4 | 9.1 | Already was using a digital/virtual curriculum for didactic education | 0 | 0.0 |

| Offered supplemental education not typically offered | 33 | 75.0 | Offered supplemental education not typically offered | 19 | 76.0 |

| Home institution | 30 | 90.9 | Home institution | 19 | 100 |

| AO Spine | 17 | 51.5 | AO Spine | 12 | 63.2 |

| NASS | 10 | 30.3 | NASS | 4 | 21.1 |

| Other Professional Society | 11 | 33.3 | Other Professional Society | 5 | 26.3 |

| Industry | 20 | 60.6 | Industry | 9 | 47.4 |

| Collaborative Education Groups* | 20 | 60.6 | Collaborative Education Groups* | 8 | 42.1 |

| Other† | 1 | 3.0 | Other | 1 | 5.3 |

| Contact with Other Spine Fellows during Pandemic | Contact with Other Fellowship Directors about Fellow Education | ||||

| Yes | 19 | 43.2 | Yes | 12 | 48.0 |

| No | 25 | 56.8 | No | 13 | 52.0 |

| Felt connected to other fellows during pandemic | Felt connected to other fellowship directors during pandemic | ||||

| Yes | 23 | 52.3 | Yes | 13 | 52.0 |

| No | 21 | 47.7 | No | 12 | 48.0 |

| Concern regarding COVID impact on future job start date | Believes current fellow education has suffered due to COVID | ||||

| Yes | 11 | 25.0 | Yes | 17 | 68.0 |

| No | 27 | 61.4 | No | 8 | 32.0 |

| No job lined up | 6 | 13.6 | |||

| Cancelled job interviews | |||||

| Yes | 10 | 22.7 | |||

| No | 34 | 77.3 |

Example, Seattle Science Foundation, Vumedi, etc.

Free response included “Virtual Global Spine Conference”.

DISCUSSION

The novel coronavirus is the first public health emergency to affect the United States since the expansion of orthopedic and neurological training programs to include spine-specific fellowships. Given that nearly all orthopedic residents who pursue spine surgery rely upon fellowship to develop their clinical acumen and operative skill set, the anxiety and uncertainty regarding training in the time of COVID-19 is understandable. Several recent editorials discuss the impact of COVID-19 on orthopedic resident18,19 and spine surgery training.15,20 Spine fellows in New York City described how they were redeployed to non–spine-related patient care when all elective spine cases were cancelled; yet their primary modes of continued education occurred virtually through webinars and online conferences.15 We analyzed input from >43% of spine fellows and 61% of spine fellowship directors in AO Spine accredited programs to better understand the current state of spine surgery training in the wake of this pandemic, to assess the impact of this pandemic on fellow readiness for practice, and to discuss future considerations in the training of spine surgeons.

Fellows and fellowship directors universally reported a stoppage of elective spine cases as of mid-March 2020. This was associated with a decrease in overall spine case volume, a greater than 50% reduction in fellow work hours per week, and predictions of 11%–25% fewer spine cases at the time of graduation. To ensure continued learning opportunities, most fellows and directors reported transitioning their curriculum to a webinar-type platform similar to those reported in the editorial literature regarding spine,15 orthopedic,18 and neurological surgery training programs.21 The conversion to remote learning practices has been individualized and has likely not undergone the rigorous quality processes of traditional medical educational opportunities. As such, there is an opportunity to define quality measures for remote surgical education as well as to innovate beyond webinars and virtual classrooms.

Despite the reduction in clinical and surgical spine experiences, and in light of supplemental education opportunities, fellows and fellowship directors were only slightly concerned that the temporary suspension of elective surgeries would negatively impact fellow readiness to start practice. However, 27% of fellows reported expressing concern to their fellowship director regarding preparedness for practice and 32% of fellowship directors reported hearing similar concerns from their fellows. This apprehension is understandable for orthopedic trained surgeons who perform fewer spine procedures in residency compared to their neurological surgeon counterparts.22,23 Moreover, surveyed fellows expect to complete an average of ~240 cases before the end of the academic year, which is less than the 250 cases cited by several authors as the ideal caseload for fellowship.13–15 Notably, however, only 2 fellowship directors believed that COVID-19 would affect successful fellowship completion. The difference in concern voiced by the fellows compared with the assurance offered by the fellowship directors suggests that self-confidence in clinical and surgical skills comes with experience. Some fellows may feel the need to complete a certain number of cases to prove competency to themselves whereas fellowship directors may be focused on core competencies. The inclusion of a more robust virtual spine education may serve to augment the traditional fellowship experience and ultimately increase confidence among graduating spine fellows.

The COVID-19 crisis raises the question of whether the current time-based fellowship model is the most effective method for training competent spine surgeons. Over the last 2 decades, academic orthopedic and neurological surgery communities have begun to introduce the concept of competency-based education.24,25 The American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery, in cooperation with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, initiated a project to define and assess the essential knowledge, skills, and behaviors that need to be acquired by orthopedic residents during training in order for them to be competent for independent practice.24 However, the adoption of competency-based surgical education has been slow and met with resistance due to concerns regarding implementation and lack of normative data to compare across programs.26 Fellowship training in the era of COVID-19 provides an even more striking example of the importance of a competency-based model and highlights an opportunity to reshape fellow education toward a more substantial and acceptable format than has been achieved through the ACGME’s current offerings.

Given the variability in operative spine volume among orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery residents,23 an argument for a categorical spine residency has been presented.27 Graduating orthopedic surgery residents completed an average of 82.8 spine cases during their training, up to 6-times fewer total spine procedures compared with neurosurgery residents.23 The current crisis highlights a potential fragility of the current spine surgeon training model. Missing 11%–25% of fellowship cases may lead to a substantial reduction in overall spine training before entering practice. A categorical spine residency would potentially allow for a greater breadth of education with greater capacity to absorb future crises. Only time will tell whether current fellows’ lost clinical and surgical experience will have a meaningful impact.

Lastly, current spine surgery fellows are concerned about the job market and the impact of the pandemic on their future job status. Although the majority of spine fellows reported having a job lined up for after graduation, >25% were concerned about their job offer being rescinded or employment delayed. Given that manyhospitals and practices have been forced to furlough employees,28 the concern from current spine fellows is well-founded and demonstrates the reality of health care economics during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This is an opportunity to expand the depth of fellow training to include formal educational content on the business of medicine. A validated educational curriculum will inform fellows on a broader economic perspective as well as their professional opportunities.

This survey-based study is not without limitation. First, the response rate, although greater than expected for an external survey, is somewhat modest. Response bias may increase risk for lower study validity. Next, our assessment did not address the impact of COVID-19 on fellows’ experiences in treating patients in the clinic setting. Finally, although we gathered perspectives on trainee competency, we did not directly measure the impact of COVID-19 on surgical or clinical acumen. Despite these recognized limitations, we believe these results offer early insight into the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on spine fellowship training, provide reassurance for spine fellowship directors concerned about their programs, and support discussions of reshaping spine surgery curricula to maximize trainee aptitude and confidence.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly triggered increased levels of anxiety and concern among spine surgery trainees. This survey of spine surgery fellows and fellowship directors should be reassuring that graduating spine surgeons are prepared to enter practice despite the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on fellowship training. The survey highlights a number of opportunities for improvement and innovation in the future training of spine surgeons.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Elizabeth Walker, Chi Lam, and members of AO Spine North America fellowship committee for the assistance with the dissemination of the survey.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Munster VJ, Koopmans M, van Doremalen N, et al. A novel coronavirus emerging in China—key questions for impact assessment. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:692–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr J, Podolsky SH. A national medical response to crisis—the legacy of world war II. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:613–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages—the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burrer S, De Perio M, Hughes M, et al. CDC Covid-10 Response Team. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19—United States, February 12–April 9, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69:477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AAOS. Navigating the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available at: https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/about/covid-19/aaos-clinical-considerations-during-covid-19.pdf.

- 6.Stinner DJ, Lebrun C, Hsu JR, et al. The orthopaedic trauma service and COVID-19—practice considerations to optimize outcomes and limit exposure. J Orthop Trauma. 2020;34:333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnaout O, Patel A, Carter B, et al. Letter: adaptation under fire: two harvard neurosurgical services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurosurgery. 2020;87:E173–E177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnally CJ, Shenoy K, Vaccaro AR, et al. Triaging spine surgery in the COVID-19 era. Clin Spine Surg. 2020;33:129–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NASS. COVID-19 Guidelines. Burr Ridge, IL. 2020. Available at: https://www.spine.org/Portals/0/assets/downloads/Publications/NASSInsider/NASSGuidanceDocument040320.pdf.

- 10.Zou J, Yu H, Song D, et al. Advice on standardized diagnosis and treatment for spinal diseases during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Asian Spine J. 2020;14:258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boszczyk BM, Mooij JJ, Schmitt N, et al. Spine surgery training and competence of European Neurosurgical Trainees. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009;151:619–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horst PK, Choo K, Bharucha N, et al. Graduates of orthopaedic residency training are increasingly subspecialized a review of the American board of orthopaedic surgery part II database. J Bone Joint Surg. 2015;97:869–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGuire KJ. Spine fellowships. Clin Orthop Related Res. 2006:244–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konczalik W, Elsayed S, Boszczyk B. Experience of a fellowship in spinal surgery: A quantitative analysis. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(suppl 1):S40–S54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowdell JE, Louie PK, Virk S, et al. Spine fellowship training reorganizing during a pandemic: perspectives from a tertiary orthopaedic specialty center in the epicenter of outbreak. Spine J. 2020;20:1381–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. Br Med J. 1995;33:944–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Census Bureau. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. 2010. Available at: https://www.census.gov/prod/1/gen/95statab/preface.pdfhttp://www.census.gov/prod/1/gen/95statab/preface.pdf.

- 18.Kogan M, Klein S, Hannon C, et al. Orthopaedic education during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:e456–e464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stambough JB, Curtin BM, Gililland JM, et al. The past, present, and future of orthopedic education: lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:S60–S64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bambakidis NC, Tomei KL. Editorial. Impact of COVID-19 on neurosurgery resident training and education. J Neurosurg. 2020;133:10–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomlinson SB, Hendricks BK, Cohen-Gadol AA. Editorial. Innovations in neurosurgical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: is it time to reexamine our neurosurgical training models? J Neurosurg. 2020;133:14–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daniels AH, Ames CP, Smith JS, et al. Variability in spine surgery procedures performed during orthopaedic and neurological surgery residency training: an analysis of ACGME case log data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pham MH, Jakoi AM, Wali AR, et al. Trends in spine surgery training during neurological and orthopaedic surgery residency: a 10-year analysis of ACGME case log data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:e122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nousiainen M, Incoll I, Peabody T, et al. Can we agree on expectations and assessments of graduating Residents? 2016 AOA Critical Issues Symposium. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long DM. Competency-based residency training: the next advance in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2000;75:1178–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ames SE, Ponce BA, Marsh JL, et al. Orthopaedic surgery residency milestones: initial formulation and future directions. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:e1–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daniels AH, Ames CP, Garfin SR, et al. Spine surgery training: is it time to consider categorical spine surgery residency? Spine J. 2015;15:1513–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barker N, Andreoli E, McWilliams T. COVID-19 and its impact on physician compensation. Becker’s Hosp Rev. 2020. Available at: www.beckershospitalreview.com/covid-19-and-its-impact-on-physician-compensation.html. [Google Scholar]