Abstract

Background

Breast cancer (BC) in young women is characterized by an unfavorable prognosis in hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative tumors, which may be explained by low rates of tamoxifen adherence. In Mexico, up to 14% of all BC diagnoses occur in young women and no data on tamoxifen adherence has been reported.

Objective

To estimate the rate of adherence to adjuvant tamoxifen in Mexican young women with BC (YWBC).

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted at the National Cancer Institute in Mexico City, among YWBC (≤40 years at diagnosis) receiving adjuvant tamoxifen. Adherence was measured subjectively, through self-reported surveys, and objectively, through medication possession ratio (MPR). Descriptive statistics were used to analyze sociodemographic characteristics. To compare associations between patients’ characteristics and adherence, Chi-square test was used for categorical variables and Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test for quantitative variables.

Results

A total of 141 YWBC receiving adjuvant tamoxifen were included. Regarding subjective adherence, 95% expressed taking tamoxifen regularly, 70% reported missing 0 doses in the past 30 days, and 71.6% reported having adverse effects. Regarding objective adherence, 74.8% of patients had an MPR ≥80%. The association between subjective and objective adherence was statistically significant (p = 0.004). Subjective adherence was associated with not skipping tamoxifen doses when feeling worse. Objective adherence was associated with having a stable job, not skipping tamoxifen doses when feeling worse, taking additional medications, and time on tamoxifen treatment. Fifty-six percent considered the information on tamoxifen to be insufficient and 37% not understandable.

Conclusion

In our study, high subjective and objective adherence rates to adjuvant tamoxifen were reported, although an important proportion of women reported high rates of adverse effects and not fully understanding the benefits of tamoxifen. Strategies to increase tamoxifen adherence may be even more important now that longer durations of treatment or further ovarian function suppression have become the standard of care in YWBC.

Keywords: young women, breast cancer, tamoxifen, adherence, Mexico

Background

In Mexico, up to 14% of all breast cancer (BC) diagnoses occur in young women (≤40 years at diagnosis), compared to 5–7% in the United States (US) and Canada.1,2 Moreover, a higher proportion of advanced-stage disease at diagnosis has been reported in Mexican young women (48%)3 in contrast to young women in other countries such as, the US (17%)4 and New Zealand (27%).5 BC in young women is characterized by an unfavorable prognosis, advanced-stage at diagnosis, higher proportion of aggressive subtypes, and greater systemic recurrence rates in comparison with post-menopausal women.6–9 Furthermore, young women with BC (YWBC) with hormone receptor (HR)-positive and HER2-negative tumors have a higher risk of recurrence and death compared to their older counterparts.9–12

Several theories have been proposed for the unfavorable prognosis in HR-positive and HER2-negative tumors in YWBC, including tamoxifen failure/resistance10 and a greater proportion of luminal B tumors with worse prognosis than luminal A tumors.9,13 Another factor that might contribute to poor outcomes is the reported low rate of adjuvant tamoxifen adherence in YWBC.14,15

Recent guidelines published by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommend adjuvant treatment with tamoxifen for at least five and up to 10 years for premenopausal women with HR-positive BC.16 In spite of the benefit in recurrence free and overall survival with endocrine treatment,17,18 current evidence has shown that up to 60% of women with BC interrupt or discontinue tamoxifen before completing five years of therapy, therefore increasing their risk of cancer-related death.17–19 Thus, newer recommendations with longer tamoxifen treatment duration and/or further estrogen deprivation in YWBC may pose a greater challenge for adherence.

Although young age has been described as a predictor of tamoxifen nonadherence,14,15,20–24 no data regarding this issue among YWBC in Latin America has been reported. Therefore, the aim of this study was to estimate the rate of adherence to adjuvant tamoxifen in Mexican YWBC and assess the factors that may influence patients’ adherence to treatment.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted at the National Cancer Institute (Instituto Nacional de Cancerología [INCan]) in Mexico City. From June to December 2015, women aged 40 years or younger at BC diagnosis who were receiving adjuvant treatment with tamoxifen were invited to participate. Patients were invited to participate in person before or after their medical appointments with BC oncologists. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and provided written consent. Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee (Comité de Ética en Investigación and Comité de Investigación) (Prot. No 015/036/OMI CEI/992/15) and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Definitions

Adherence represents the extent to which patients act in accordance with the prescribed treatment regimen.25 According to the World Health Organization, adherence can be evaluated through subjective and objective measures.25 In this study, we aimed to measure adherence subjectively, through self-reported surveys, and objectively, through the medication possession ratio (MPR). MPR refers to the number of doses dispensed in relation to the dispensing period.24 MPR was calculated for each patient by summing up the quantity of tamoxifen tablets dispensed at INCan’s pharmacy and dividing the amount of medication dispensed by the time since tamoxifen was first prescribed to the date this analysis was done, and was expressed as a percentage.19,26 A MPR ≥ 80% was considered adherent.14,27,28 Noteworthy, tamoxifen was dispensed free of charge at INCan’s pharmacy for all patients with BC.

Procedures

Socio-demographic characteristics were obtained from medical records and self-applied surveys. Variables regarding patients’ use and attitudes towards tamoxifen treatment and adherence were collected from a self-reported survey with multiple-choice questions. The survey was developed based on items or questions asked in prior studies on adherence to endocrine therapy in women with BC21,22,29,30 and a final version was approved by a local panel of breast cancer specialists, including two medical oncologists, two psycho-oncologists, a patient navigator, and a clinical researcher with expertise in the field.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze sociodemographic characteristics. To compare associations between selected variables and patients’ subjective and objective adherence to tamoxifen, Chi-square test was used for categorical variables and Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test for quantitative variables according to their distribution. We further analyzed the association between subjective and objective adherence using the Chi-square test. Variables associated with univariable p value < 0.05 were evaluated in a multivariable logistic regression model. A value of p< 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The software used for data analysis was SPSS, version 25.0.

Results

One-hundred fifty-one eligible patients were invited to participate in person before or after the medical appointment. Ninety percent of them accepted to participate and answered the survey, 5% had family members attending the hospital instead of them, and 5% were not reached. None of the included patients were on ovarian function suppression. A total of 141 YWBC were included in the final analysis. Mean age at diagnosis was 35.7 years (range: 19–40), 65% had early stage at diagnosis, and mean time on tamoxifen treatment was 26.7 months. Thirty-three percent had higher education, 50.4% were married or living in a domestic partnership and 34% had no children at diagnosis. Only 24.8% of participating women reported having a stable job. Seventy percent of patients expressed financial issues, with 45% being able to pay bills through cutting back and 39% paying bills with difficulty. Almost half of the patients (49%) reported having a social support network of six or more persons. Complete sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. An anonymous database with patients’ characteristics and responses to the survey is found in Supplement 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

| n = 141 (100%) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age at diagnosis (SD) | 35.7 (±4.4) |

| Stage at diagnosis | |

| Early stage (0, I, II) | 92 (65.2) |

| Advanced stage (III and IV) | 45 (31.9) |

| Unknown | 4 (2.9) |

| Mean time on tamoxifen treatment (SD) | 26.7 months (± 17.2) |

| Education | |

| Elementary school | 13 (9.2) |

| Middle school | 45 (31.9) |

| High school | 37 (26.2) |

| University | 46 (32.6) |

| Marital status | |

| Unpartnered (single/divorcee/widow) | 70 (49.6) |

| Partnered (married/in a domestic partnership) | 71 (50.4) |

| Stable job at time of survey (yes) | 35 (24.8) |

| Number of children at diagnosis | |

| 0 | 48 (34) |

| 1 | 25 (17.7) |

| 2 | 43 (30.5) |

| 3 | 21 (14.9) |

| ≥ 4 | 4 (2.8) |

| Number of children at time of survey | |

| 0 | 47 (33.3) |

| 1 | 24 (17) |

| 2 | 44 (31.2) |

| 3 | 21 (14.9) |

| ≥ 4 | 5 (3.5) |

| Perceived financial problems | |

| Yes | 99 (70.2) |

| No | 42 (29.8) |

| Perceived financial status | |

| Money for extras | 4 (2.8) |

| Little money for extras | 19 (13.5) |

| Pay bills through cutting back | 63 (44.7) |

| Difficulty paying bills | 55 (39) |

| Number of people that contribute economically in the household | |

| 0 | 10 (7.1) |

| 1–2 | 119 (84.4) |

| 3–4 | 10 (7.1) |

| 5–6 | 2 (1.4) |

| Psychological support since diagnosis | |

| Yes | 62 (44) |

| No | 79 (56) |

| Number of people in social support network | |

| 0 | 5 (3.5) |

| 1–2 | 32 (22.7) |

| 3–4 | 23 (26.3) |

| 5–6 | 12 (8.5) |

| ≥ 6 | 69 (48.9) |

Self-Reported Survey – Subjective Adherence

Ninety-five percent of patients expressed taking tamoxifen regularly and 70% reported missing 0 doses of tamoxifen in the past 30 days. When asked how frequently they forget to take their medication, 61% answered never, while only 1.4% reported frequently forgetting. When asked if they skipped a dose or if they modified the prescribed doses, 97.9% communicated they had never taken those actions. Ninety-one percent of patients reported never skipping a dose of tamoxifen when feeling worse. Almost two-thirds of patients (65.2%) expressed that they had the opportunity to ask questions regarding adjuvant tamoxifen before initiating endocrine therapy. Fifty-six percent considered the information about tamoxifen treatment was not sufficient and 36.9% perceived the information not understandable. Up to 71.6% of women reported experiencing adverse effects, most of them being menopausal-related events (64.4%). Complete results of the self-reported survey are found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Self-Reported Survey

| n = 141 (100%) | |

|---|---|

| Do you take tamoxifen regularly? | |

| Yes | 134 (95) |

| No | 7 (5) |

| How many doses of tamoxifen have you missed in the last month (30 days)? | |

| 0 (100% adherent) | 98 (69.5) |

| 1–6 (80–99% adherent) | 35 (24.8) |

| 7–30 (<80% adherent) | 7 (5) |

| Do you ever forget to take tamoxifen? | |

| Never | 86 (61) |

| Rarely | 45 (31.9) |

| Sometimes | 8 (5.7) |

| Often | 2 (1.4) |

| Always | 0 (0) |

| Sometimes if you feel worse when you take tamoxifen, do you stop taking it? | |

| Never | 128 (90.8) |

| Rarely | 6 (4.3) |

| Sometimes | 6 (4.3) |

| Often | 1 (0.6) |

| Always | 0 (0) |

| Do you alter the dose of tamoxifen from what has been prescribed by your physician? | |

| Never | 138 (97.9) |

| Rarely | 2 (1.4) |

| Sometimes | 1 (0.7) |

| Often | 0 (0) |

| Always | 0 (0) |

| Do you take other medications in addition to tamoxifen? | |

| Yes | 47 (33.3) |

| No | 94 (66.7) |

| If yes, how many medications do you take in addition to tamoxifen? | |

| 1 | 17 (36.2) |

| 2 | 15 (31.9) |

| 3 | 9 (19.1) |

| 4 | 3 (6.4) |

| ≥ 5 | 1 (2.1) |

| Did you have the opportunity to ask your physician questions about tamoxifen before treatment initiation? | |

| Yes | 92 (65.2) |

| No | 49 (34.8) |

| Do you consider that the information provided by your physician regarding tamoxifen was sufficient? | |

| Yes | 62 (44) |

| No | 79 (56) |

| Do you consider that the information provided by your physician regarding tamoxifen was understandable? | |

| Yes | 89 (63.1) |

| No | 52 (36.9) |

| Have you experienced side effects from tamoxifen? | |

| Yes | 101 (71.6) |

| No | 40 (28.4) |

| If so, which are the most important side effects that you have experienced from tamoxifen? | |

| Menopause-related symptoms | 65 (64.4) |

| General symptoms | 50 (49.5) |

| Articular symptoms | 24 (23.8) |

| Other symptoms | 25 (24.8) |

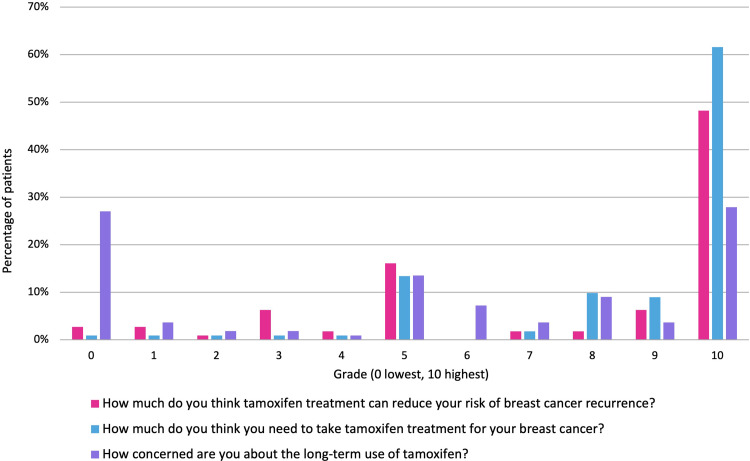

Perceptions towards tamoxifen were graded from 0 to 10, 0 being the lowest score (needing it the least or least benefit) and 10 being the highest score (needing it the most or most benefit). Forty-eight percent thought it significantly reduced their risk of recurrence (grade 10) and 62% strongly believed they needed to receive tamoxifen treatment (grade 10). Of note, only 28% were worried about the long-term effects the therapy may cause (grade 10). Figure 1 shows participants’ grading answers.

Figure 1.

Graded perceptions towards tamoxifen.

MPR – Objective Adherence

Data for calculating MPR were only available for 107 patients. Mean MPR was 88.6% ± 18.2%. MPR was ≥80% for 74.8% and <80% for 25.2% of patients.

Association Between Subjective and Objective Adherence

Seventy-nine patients (77.5%) with MPR ≥80% expressed being adherent in the self-reported survey, while four (80%) reported being not adherent in the self-reported survey and had an MPR <80%, as shown in Table 3. The association between subjective and objective adherence was statistically significant (p = 0.004).

Table 3.

Association Between Subjective an Objective Adherence

| MPR <80% n = 27 | MPR ≥80% n = 80 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported adherence | 23 (22.5%) | 79 (77.5%) | 0.004 |

| Self-reported non-adherence | 4 (80%) | 1 (20%) |

Associations Between Adherence and Patients’ Characteristics

Subjective adherence was statistically associated only with not skipping tamoxifen doses when feeling worse (p< 0.001). Objective adherence was statistically associated with having a stable job (p = 0.046), not skipping tamoxifen doses when feeling worse (p = 0.005), taking additional medications (p = 0.018), and time on tamoxifen treatment (p = 0.008). Adherence, subjectively and objectively, was not statistically associated with age at diagnosis, clinical stage, education level, marital status, number of children, perceived financial difficulties, psychological support since diagnosis, number of persons in support network, having asked questions about tamoxifen before treatment initiation, considering information about tamoxifen understandable and sufficient, or experiencing side effects. Associations between adherence and patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 4. In the multivariate analysis, not skipping tamoxifen doses when feeling worse (p = 0.003), taking additional medication (p = 0.036), and time on tamoxifen treatment (p = 0.001) remained statistically significant.

Table 4.

Associations Between Adherence and Patients’ Characteristics

| Subjective Adherence | Objective Adherence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Does Not Take Tamoxifen Regularly n = 7 (100%) | Takes Tamoxifen Regularly n = 134 (100%) | MPR <80 n = 27 (100%) | MPR ≥80 n = 80 (100%) | |

| Mean age at diagnosis | 35.71 | 35.7 | 35.89 | 35.96 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||

| Stage (0, I, II) | 4 (57.1) | 88 (67.7) | 18 (66.7) | 52 (66.7) |

| Stage (III, IV) | 3 (42.9) | 42 (32.3) | 9 (33.3) | 26 (33.3) |

| Time on tamoxifen treatment (months) | 28.5 | 25.5 | 37.9 | 21.3 |

| Education level | ||||

| Elementary school | 1 (14.3) | 12 (9) | 2 (7.4) | 8 (10) |

| Middle school | 3 (42.9) | 42 (31.3) | 9 (33.3) | 25 (31.3) |

| High school | 2 (28.6) | 35 (26.1) | 6 (22.2) | 26 (32.5) |

| University | 1 (14.3) | 45 (33.6) | 10 (37) | 21 (26.3) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Unpartnered (single/divorcee/widow) | 2 (28.6) | 68 (50.7) | 11 (40.7) | 42 (52.5) |

| Partnered (married/domestic partnership) | 5 (71.4) | 66 (49.3) | 16 (59.3) | 38 (47.5) |

| Stable job at time of survey (yes) | 2 (28.6) | 33 (24.6) | 11 (40.7) | 17 (21.3) |

| Number of children at diagnosis | ||||

| 0 | 1 (14.3) | 47 (35.1) | 8 (29.6) | 26 (32.5) |

| ≥1 | 6 (85.7) | 87 (64.9) | 19 (70.4) | 54 (67.5) |

| Number of children at time of survey | ||||

| 0 | 1 (14.3) | 46 (34.3) | 8 (29.6) | 26 (32.5) |

| ≥1 | 6 (85.7) | 88 (65.7) | 19 (70.4) | 54 (67.5) |

| Perceived financial problems (yes) | 5 (83.3) | 94 (70.1) | 19 (70.4) | 58 (72.5) |

| Perceived financial status | ||||

| Money for extras | 0 | 4 (3) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (3.8) |

| Little money for extras | 1 (14.3) | 18 (13.4) | 6 (22.2) | 6 (7.5) |

| Pay bills through cutting back | 4 (57.1) | 59 (44) | 10 (37) | 40 (50) |

| Difficulty paying bills | 2 (28.6) | 53 (39.6) | 10 (37) | 31 (38.8) |

| Number of people that contribute economically in the household | ||||

| 0–2 | 7 (100) | 122 (91) | 24 (88.9) | 74 (92.5) |

| 3–6 | 0 | 12 (9) | 3 (11.1) | 6 (7.5) |

| Psychological support since diagnosis | 5 (71.4) | 57 (42.5) | 10 (37) | 37 (46.3) |

| Number of people in social support network | ||||

| 0–6 | 4 (57.1) | 68 (50.7) | 15 (55.6) | 43 (53.8) |

| ≥6 | 3 (42.9) | 66 (49.3) | 12 (44.4) | 37 (46.3) |

| Sometimes if you feel worse when you take tamoxifen, do you stop taking it? | ||||

| Never | 3 (42.9) | 125 (93.3) | 20 (74.1) | 76 (95) |

| Rarely/Sometimes/Often/Always | 4 (57.1) | 9 (6.7) | 7 (25.9) | 4 (5) |

| Do you take other medications in addition to tamoxifen? (yes) | 1 (14.3) | 46 (34.3) | 4 (14.8) | 33 (41.3) |

| Did you have the opportunity to ask your physician questions about tamoxifen before treatment initiation? (yes) | 4 (57.1) | 88 (65.7) | 18 (66.7) | 55 (68.8) |

| Do you consider that the information provided by your physician regarding tamoxifen was sufficient? (yes) | 2 (28.6) | 60 (44.8) | 15 (55.6) | 39 (48.8) |

| Do you consider that the information provided by your physician regarding tamoxifen was understandable? (yes) | 2 (28.6) | 87 (64.9) | 19 (70.4) | 54 (67.5) |

| Have you experienced side effects from tamoxifen? (yes) | 6 (85.7) | 95 (70.9) | 19 (70.4) | 57 (71.3) |

Discussion

The standard of care for YWBC with HR-positive tumors is to receive five to 10 years of adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen, with or without concomitant ovarian function suppression.16,17,31 Ensuring adherence to such treatment is critical, since several studies have shown that women receiving tamoxifen for less than five years have higher recurrence rates and an increased risk of death compared to those receiving treatment for five to 10 years.17–19,32–35

Young age has been described as one of the main predictors of tamoxifen non-adherence and discontinuation.14,15,20–24 Three studies have focused solely on describing tamoxifen adherence rates in YWBC. In a prospective study evaluating tamoxifen adherence in 196 YWBC, Cluze et al. reported that at least 42% of them had an interruption (defined as two or more consecutive months of tamoxifen interruption, based on pharmacy refill) within the first two years of tamoxifen treatment and this was possibly related to lack of clear information regarding endocrine therapy and lack of social support.21 Furthermore, in a retrospective study by Huiart et al., 29.7% of YWBC discontinued tamoxifen treatment by the second year of therapy.22 Moreover, in a recent analysis of the HOHO prospective cohort, 51% of 384 YWBC reported at least one nonadherent behavior, and 18% reported moderately/highly nonadherent behaviors.36

Additionally, low adherence rates to adjuvant endocrine therapy among women with a low socioeconomic status have been described in previous studies in the US and Nigeria. A study by Kimmick et al. among women with Medicaid (a health program for low-income individuals in the US) found that the adherence rate to adjuvant endocrine treatment measured by MPR was only 60%.27 A report from Nigeria by Oguntola et al. found an adherence rate of 66% in women ≤45 years compared to 85% in women ≥65 years, although age was not statistically associated with adherence.37

To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating tamoxifen adherence rates specifically in YWBC in a resource-constrained setting in Latin America. Our initial perception was that Mexican YWBC would have low adherence rates due to patients’ disadvantaged socioeconomic status, poor education levels, and lack of known benefit of tamoxifen therapy, as well as the limited availability of educational resources to reinforce tamoxifen use.

Unexpectedly, YWBC in our study expressed higher rates of subjective adherence to tamoxifen (95%) than reported in the literature for young and older women in other regions.29,30,37,38 In the HOHO study, 80% of women reported taking their endocrine therapy exactly as prescribed over the last three months.36 Similarly, a study from the United Kingdom reported a high tamoxifen adherence rate of 88% through self-reported surveys.38 However, it has been recognized that data collected from self-applied surveys may overestimate adherence due to distortion caused by patient recall or desire to give socially acceptable answers.22,39 For example, in a subcohort of 1177 premenopausal women from the prospective CANTO trial, adherence to tamoxifen was measured through tamoxifen serum levels and self-reported adherence one year after prescription. In this study, nonadherence rates were low, with 16% of patients having serum measurement of tamoxifen below the set adherence threshold and 12.3% patients self-reporting nonadherence. However, out of the 188 patients with tamoxifen serum levels below the adherence threshold, 55% self-reported adherence to tamoxifen, reflecting that nonadherent women might not overtly acknowledge this behavior.40

In an effort to understand the patterns of adherence in Mexican young women, we searched for evidence on treatment adherence in similar resource settings, focusing mainly on populations with chronic comorbidities that require oral medications in Latin America. A 2018 meta-analysis by Costa et al., which included 22,603 participants from 53 studies, described that the adherence rate to antiretroviral therapy in Latin America was 70%, similar to that identified by studies conducted in high-income regions. It also found that studies conducted in low- or lower-middle-income countries showed higher adherence rates (83%) than in middle-income countries (70%).41 Similarly, Uthman et al. found that the adherence rate to antiretroviral therapy was significantly higher in low-income countries (86%) compared to high‐income countries (67.5%).42 One possible explanation for the high adherence rates reported in these populations may be that the availability of clinical trials in the low- and middle-income settings allows for adherence counselling and additional support for participants.

Several factors have been associated with high tamoxifen adherence in different studies, including patients' beliefs about the prescribed medicine,21 high social support network,22,43–45 higher education,24 having a partner,24 and managing side effects.45 We studied the association between tamoxifen adherence and various factors to help explain the high proportion of adherence found in our study; however, only the number of additional medications, not skipping doses of tamoxifen when feeling worse and having a stable job were statistically significant.

Moreover, treatment-related information provided by health professionals has a strong impact on tamoxifen adherence rate.16,21 A significant proportion of our patients (65.2%) reported having discussed tamoxifen therapy with their providers prior to treatment initiation. This contrasts with a European survey on patient knowledge about adjuvant endocrine therapy for early BC, where less than one-third of women received information about the risk of their cancer recurring and the possible long-term effects of the treatments.46 In spite of receiving initial information on tamoxifen use, 56% and 36.9% of our patients did not consider the information provided by their physicians as sufficient and understandable, respectively. This might be associated with a negative impact on persistence to treatment, as previously reported.21,47

Furthermore, patients’ beliefs and perceptions about prescribed treatments have been described as important predictors of adherence.16,48 While a negative perception of benefits versus risks of tamoxifen therapy has been associated with interruption and low adherence rates in older women with BC,30,38,49 the higher adherence rates seen in our population may be attributed to their reported high perception of benefits of tamoxifen. Similarly, a previous study found that providing clear information on the benefits of tamoxifen treatment and possible long-term effects of therapy were statistically significant predictors of adherence.50

Experiencing adverse effects has been identified as a major determinant for tamoxifen discontinuation.47,51–54 Menopausal adverse events, such as hot flashes, dyspareunia, menstrual disorders, and fluid retention have greatly affected adherence rates to tamoxifen in YWBC.21,55 While our patients reported a high adherence to tamoxifen treatment, more than two-thirds reported having adverse effects. This might contribute to late tamoxifen discontinuation, as it has been described that with longer follow-up more patients abandon endocrine treatment.15,22,43,56 Furthermore, in a qualitative study by Moon et al., women felt that their physicians did not offer the support they needed in dealing with side effects, dismissed or belittled the side effects they were experiencing and did not provide any coping strategies on how to reduce the impact of those side effects on their quality of life.57

Furthermore, longer duration on tamoxifen treatment has been associated with lower rates of adherence and higher rates of discontinuation over time.15,19,22,43 Likewise, our patients reported decreased adherence to tamoxifen with longer duration on treatment. A previous study found evidence that restarting adjuvant hormone therapy after discontinuation is associated with better BC outcomes.58 These findings suggest that interventions should be carried out during the whole period of tamoxifen treatment, reaffirming patients on the benefits of 5-year therapy on overall survival, managing side effects and restarting treatment in those who interrupted it.

Another important factor that might impact adherence in this reproductive-aged group is family-building decisions, as suggested by previous authors.59,60 Llarena et al. reported that fertility concerns negatively impacted tamoxifen initiation and continuation among premenopausal patients.61 As a previous study from our group found that more than a third of our patients had no children prior to BC diagnosis and were concerned about infertility issues,62 we hypothesized that non-adherence would be associated with not having children prior to BC diagnosis; however, this association was not found in this study.

Successful strategies to promote adherence are complex and require great efforts, especially since they need to be maintained over the entire course of treatment.22 An option might be to systematically provide patients with verbal and/or written information regarding tamoxifen treatment during follow-up visits. Our group previously showed that up to 80% of underserved young Mexican women own a smartphone or tablet and would like to receive more information in an electronic format.63 Therefore, other innovative strategies, such as reminders through e-mail, social media or mobile applications, may be useful and easier to implement.

Among the limitations of this study is its cross-sectional nature, which limits the information collected to a specific moment in time, whereas a longitudinal follow-up might reveal a decreasing proportion of tamoxifen adherence across time. Also, we did not evaluate the association between subjective/objective adherence to BC outcomes, including recurrence and death. Finally, data regarding MPR was not available for all patients and might also overestimate adherence, as patients may dispense more medication than what they actually need, or underestimate it, as some patients might buy it elsewhere. The most important strength of this study is that it is the first of its kind in evaluating YWBC’s adherence to tamoxifen, both subjectively and objectively, in a limited-resource setting.

Conclusions

Improving adherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in YWBC is an important challenge for oncologists, as these patients have potentially longer life expectancies and low adherence rates in this subgroup of women have been associated with a worse survival. This study found high adherence rates to tamoxifen, both subjectively and objectively, which were associated with having a stable job, not skipping tamoxifen doses when feeling worse, taking additional medications, and time on tamoxifen treatment. Although an important proportion of women reported high rates of adverse effects and not fully understanding the benefits of tamoxifen treatment, the adherence rate of Mexican YWBC was higher than previous reports. Therefore, more time should be dedicated to describing and managing the side effects of adjuvant endocrine therapy, explaining its benefits, and emphasizing its role in decreasing the risks of BC recurrence and death. Developing strategies to increase adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy may be even more important now that longer durations of tamoxifen treatment or further ovarian function suppression with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues have become the standard of care among this growing population of YWBC.

Disclosure

The abstract of this paper was presented at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in Journal of Clinical Oncology, Volume 35, Issue 35 suppl: https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.e12003. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Villarreal-Garza C, Aguila C, Magallanes-Hoyos MC, et al. Breast cancer in young women in Latin America: an unmet, growing burden. Oncologist. 2013;18(12):1298-1306. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partridge AH, Ruddy KJ, Kennedy J, Winer EP. Model program to improve care for a unique cancer population: young women with breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(5):e105–10. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villarreal-Garza C, Platas A, Miaja M, et al. Young women with breast cancer in Mexico: results of the pilot phase of the Joven & Fuerte prospective cohort. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:395–406. doi: 10.1200/JGO.19.00264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmer AS, Zhu K, Steeg PS, et al. Analysis of breast cancer in young women in the Department of Defense (DOD) database. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;168(2):501–511. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4615-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seneviratne S, Lawrenson R, Harvey V, et al. Stage of breast cancer at diagnosis in New Zealand: impacts of socio-demographic factors, breast cancer screening and biology. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:129. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2177-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker RA, Lees E, Webb MB, Dearing SJ. Breast carcinomas occurring in young women (< 35 years) are different. Br J Cancer. 1996;74(11):1796–1800. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anders CK, Hsu DS, Broadwater G, et al. Young age at diagnosis correlates with worse prognosis and defines a subset of breast cancers with shared patterns of gene expression. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3324–3330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong Q, Valero V, Kau V, et al. Female patients with breast carcinoma age 30 years and younger have a poor prognosis: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 2001;92(10):2523–2528. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villarreal-Garza C, Mohar A, Bargallo-Rocha JE, et al. Molecular subtypes and prognosis in young Mexican women with breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(3):e95–e102. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn SH, Son BH, Kim SW, et al. Poor outcome of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer at very young age is due to tamoxifen resistance: nationwide survival data in Korea–a report from the Korean Breast Cancer Society. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2360–2368. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azim HA, Michiels S, Bedard PL, et al. Elucidating prognosis and biology of breast cancer arising in young women using gene expression profiling. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(5):1341–1351. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villarreal-Garza C, Reynoso-Noveron N, Arce-Salinas C, et al. Abstract P6-08-55: high triple-negative breast cancer prevalence and poor outcome of hormone receptor positive breast cancer among young Mexican women. Cancer Res. 2015;75(9Supplement):P6-08-55-P6-08-55. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS14-P6-08-55 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang L-C, Jin X, Yang H-Y, et al. Luminal B subtype: a key factor for the worse prognosis of young breast cancer patients in China. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:201. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1207-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4120–4128. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barron TI, Connolly RM, Bennett K, Feely J, Kennedy MJ. Early discontinuation of tamoxifen: a lesson for oncologists. Cancer. 2007;109(5):832–839. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burstein HJ, Temin S, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(21):2255–2269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 1998;351(9114):1451–1467. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11423-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan PT, et al. Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(11):1763–1768. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wuensch P, Hahne A, Haidinger R, et al. Discontinuation and non-adherence to endocrine therapy in breast cancer patients: is lack of communication the decisive factor? J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141(1):55–60. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1779-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cluze C, Rey D, Huiart L, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy with tamoxifen in young women with breast cancer: determinants of interruptions vary over time. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(4):882–890. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huiart L, Bouhnik AD, Rey D, et al. Early discontinuation of tamoxifen intake in younger women with breast cancer: is it time to rethink the way it is prescribed? Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(13):1939–1946. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pagani O, Gelber S, Colleoni M, Price KN, Simoncini E. Impact of SERM adherence on treatment effect: International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials 13–93 and 14–93. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142(2):455–459. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2757-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brito C, Portela MC, de Vasconcellos MTL. Adherence to hormone therapy among women with breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:397. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabaté E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK, Carpentier MY, Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW. Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):459–478. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2114-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimmick G, Anderson R, Camacho F, Bhosle M, Hwang W, Balkrishnan R. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3445–3451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin JH, Zhang SM, Manson JE. Predicting adherence to tamoxifen for breast cancer adjuvant therapy and prevention: table 1. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4(9):1360–1365. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanton AL, Petrie KJ, Partridge AH. Contributors to nonadherence and nonpersistence with endocrine therapy in breast cancer survivors recruited from an online research registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145(2):525–534. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2961-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lash TL, Fox MP, Westrup JL, Fink AK, Silliman RA. Adherence to tamoxifen over the five-year course. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99(2):215–220. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9193-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al. Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):107–118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swedish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. Swedish breast cancer cooperative. Randomized trial of two versus five years of adjuvant tamoxifen for postmenopausal early stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(21):1543–1549. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.21.1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geiger AM, Thwin SS, Lash TL, et al. Recurrences and second primary breast cancers in older women with initial early-stage disease. Cancer. 2007;109(5):966–974. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ulcickas Yood M, Owusu C, Buist DSM, et al. Mortality impact of less-than-standard therapy in older breast cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(1):66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bryant J, Fisher B, Dignam J. Duration of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;4181(30):56–61. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wassermann J, Gelber SI, Rosenberg SM, et al. Nonadherent behaviors among young women on adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(18):3266–3274. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oguntola AS, Adeoti ML, Akanbi OO. Non-adherence to the use of tamoxifen in the first year by the breast cancer patients in an African Population. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2011;16(1):52–56, tab. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS, Sikka P, Mittal S. Adherence beliefs among breast cancer patients taking tamoxifen. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pistilli B, Paci A, Ferreira AR, et al. Serum detection of nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen and breast cancer recurrence risk. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(24):2762–2772. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costa JDM, Torres TS, Coelho LE, Luz PM. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(1):e25066. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB. Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle- and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(3):291–307. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0220-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):602–606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Partridge AH, Avorn J, Wang PS, Winer EP. Adherence to therapy with oral antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(9):652–661. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.9.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brett J, Boulton M, Fenlon D, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer: a qualitative study of factors associated with adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:291–300. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S145784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wengström Y, Aapro M, Leto Di Priolo S, Cannon H, Georgiou V. Patients’ knowledge and experience of adjuvant endocrine therapy for early breast cancer: a European study. Breast. 2007;16(5):462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clancy C, Lynch J, OConnor P, Dowling M. Breast cancer patients’ experiences of adherence and persistence to oral endocrine therapy: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;44:101706. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.101706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):555–567. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fink AK, Gurwitz J, Rakowski W, Guadagnoli E, Silliman RA. Patient beliefs and tamoxifen discontinuance in older women with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3309–3315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bright EE, Petrie KJ, Partridge AH, Stanton AL. Barriers to and facilitative processes of endocrine therapy adherence among women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;158(2):243–251. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3871-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Owusu C, Buist DSM, Field TS, et al. Predictors of tamoxifen discontinuation among older women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):549–555. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, Adams JL, Epstein AM. Patient centered experiences in breast cancer: predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Med Care. 2007;45(5):431–439. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000257193.10760.7f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demissie S, Silliman RA, Lash TL. Adjuvant tamoxifen: predictors of use side effects, and discontinuation in older women. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(2):322–328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wouters H, Stiggelbout AM, Bouvy ML, et al. Endocrine therapy for breast cancer: assessing an array of women’s treatment experiences and perceptions, their perceived self-efficacy and nonadherence. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(6):460–467.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robinson B, Dijkstra B, Davey V, Tomlinson S, Frampton C. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in Christchurch women with early breast cancer. Clin Oncol. 2018;30(1):e9–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ziller V, Kalder M, Albert US, et al. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(January):431–436. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moon Z, Moss-Morris R, Hunter MS, Hughes LD. Understanding tamoxifen adherence in women with breast cancer: a qualitative study. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22(4):978–997. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He W, Smedby KE, Fang F, et al. Treatment restarting after discontinuation of adjuvant hormone therapy in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(10). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benedict C, Thom B, Teplinsky E, Carleton J, Kelvin JF. Family-building after breast cancer: considering the effect on adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(3):165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosenberg SM, Partridge AH. New insights into nonadherence with adjuvant endocrine therapy among young women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(10):djv245. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Llarena NC, Estevez SL, Tucker SL, Jeruss JS. Impact of fertility concerns on tamoxifen initiation and persistence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(10):djv202. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Villarreal-Garza C, Martinez-Cannon BA, Platas A, et al. Fertility concerns among breast cancer patients in Mexico. Breast. 2017;33:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Villarreal-Garza C, Platas A, Bargalló-Rocha JE, et al. Information needs and internet use of breast cancer patients in Mexico. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. [Google Scholar]