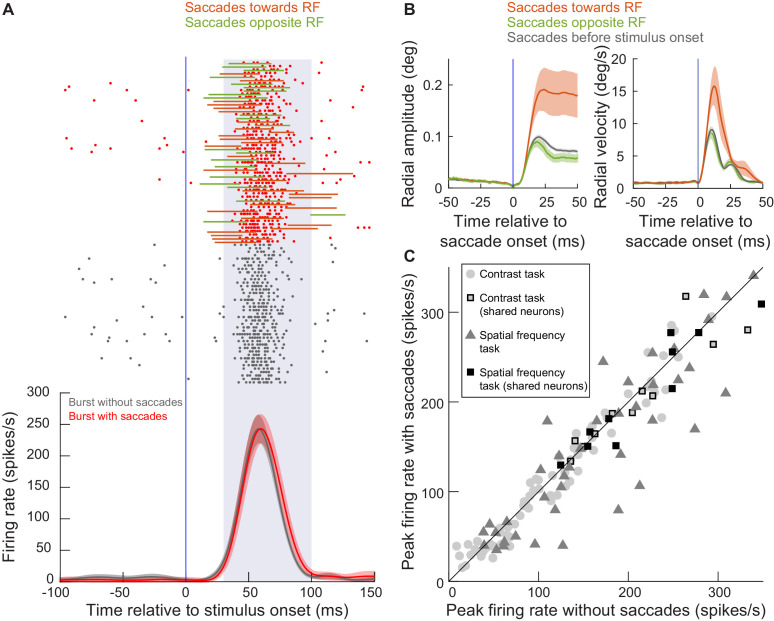

Figure 2. SC visual bursts still occurred intra-saccadically.

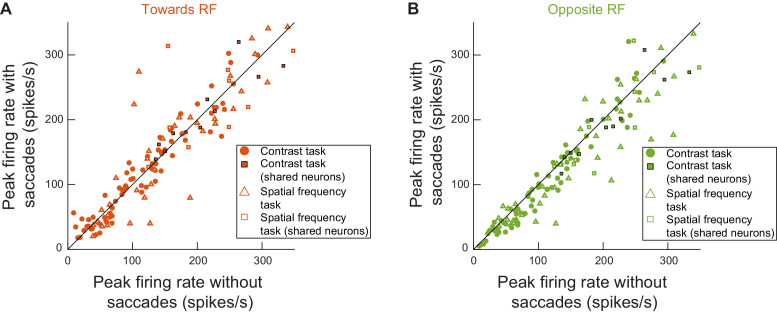

(A) We measured the firing rate of an example neuron (from experiment 1) when a stimulus appeared inside its RF without any nearby microsaccades (gray firing rate curve and spike rasters) or when the same stimulus appeared while microsaccades were being executed around the time of visual burst occurrence (red firing rate curve and spike rasters). The stimulus eccentricity was 3.4 deg. For the red rasters, each trial also has associated with it an indication of microsaccade onset and end times relative to the visual burst (horizontal lines; colors indicate whether the microsaccade was towards the RF or opposite it as per the legend). For all of the movements, the visual burst overlapped with at least parts of the movements. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals, and the shaded region between 30 and 100 ms denotes our estimate of visual burst interval. There was no statistically significant difference between peak firing rate with and without microsaccades (p=0.67, t-test). The numbers of trials and microsaccades can be inferred from the rasters. (B) For the same example session in A, we plotted the mean radial amplitude (left) and mean radial eye velocity (right) for the microsaccades towards or opposite the RF in A. The black curves show baseline microsaccade amplitude and peak velocity (for movements occurring within 100 ms before stimulus onset). Movements towards the RF were increased in size when they coincided with a peripheral visual burst; our subsequent analyses provide a mechanism for this increase. Opposite microsaccades are also shown, and they were slightly truncated. Error bars denote s.e.m. (C) At the population level, we plotted peak firing rate with saccades detected during a visual burst (y-axis) or without saccades around the visual burst (x-axis). The different symbols show firing rate measurements in either experiment 1 (contrast task) or experiment 2 (spatial frequency task); all neurons from each experiment are shown. Note that some neurons were run on both tasks sequentially in the same session (Figure 1), resulting in a larger number of symbols than total number of neurons.