Abstract

Background

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are a group of synthetic organic chlorine compounds known as an organic pollutant in food sources, which play important roles in malignancies. The present study aimed to investigate the direct effects of prevalent PCBs in food in hormone-responsive and non-responsive cell lines.

Methods

In the current study, MCF-7, LNCap, and MDA-MB231 cell lines were treated with serial concentrations (0.001–100 μM) of PCBs for 48 h and cell viability assessment was performed using MTT assay. The best concentration then applied and the expression level of PON1 was evaluated using real-time PCR. Besides, molecular docking was performed to determine the binding mechanism and predicted binding energies of PBCs compounds to the AhR receptor.

Results

Unlike MCF-7 and LNCap cells, the viability of MDA-MB231 cells did not significantly change by different concentrations of PCBs. Meanwhile, quantitative gene expression analysis showed that the PON1 was significantly more expressed in MCF-7 and LNCap lines treated with PCB28 and PCB101. However, the expression level of this gene in other groups and also MDA-MB231cells did not demonstrate any significantly change. Also, the results of molecular docking showed that PBCs had steric interaction with AhR receptor.

Conclusions

Current results showed that despite of hormone non-responsive cells the PCBs have a significant positive effect on hormone-responsive cell. Therefore, and regarding to the existence of PCBs contamination in food there should be serious concern about their impact on the prevalence of different malignancies which certainly should result in a standard limit for this material.

Graphical abstract

This study aimed to investigate the direct effects of prevalent PCBs in food in hormone-responsive and non-responsive cell lines. Cell lines were treated with serial concentrations of PCBs and cell viability assessment was performed using MTT assay. The expression level of PON1 was evaluated using real-time PCR. Molecular docking was performed to determine the binding mechanism and predicted binding energies of PBCs compounds to the AhR receptor. PCBs contamination in food there should be serious concern about their impact on the prevalence of different malignancies which certainly should result in a standard limit for this material.

Keywords: Aryl hydrocarbon receptor, Cell viability, Food contamination, Molecular docking, PON1

Introduction

Organic pollution is one of the most serious problems in the food industry around the world. The sources of this pollution are diverse and include industries, municipalities, and agriculture [1]. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are a group of synthetic organic chlorine compounds commonly used in some manufactures, as vehicles for pesticides, and in building materials. These compounds include 209 different congeners that classified into various subgroups in the case of the number and position of chlorines on the biphenyl ring [2]. The PCBs are a subset of halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons that have a strong hydrophobic function.

The toxic PCBs alone are highly unsustainable, but these are quickly absorbed by plants and animals and their stability increased [3, 4]. The toxic forms of PCBs found in many environmental pollutants are sustained in organisms and may lead to immunological, neurological, and endocrinological consequences in the population [3]. These compounds have been identified in many industrial foods. The percentage of PCBs congeners in industrial food products is defined by the Food and Drug Administration and if there is a high percentage in the products, production and distribution licenses are not issued and these products are eliminated. The current European Union maximum residue limits (MRLs) for organochlorine pesticide residues 10–50 μg/kg have been reported for a wide range of food products [5].

The classification of PCBs is based on chlorine residues in their chemical structure and can be divided into two main groups: dioxin-like (DL) and non-dioxin like (NDL). DL-PCB compounds have biochemical properties similar to Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDD) compounds that have a highly toxic capacity [6]. The concentration of PCB compounds in the blood and body secretions, especially in breast milk, would be a reflection of the pollution status of the food and environmental resources with PCB toxins [7]. The persistence of PCBs in food is a major concern for food industries. Therefore, the concentration of PCB is carefully controlled in many products of the food industry. In the food, environmental, and tissue samples, etc., six forms of PCBs (28, 52, 101, 138, 153, and 180) are prevalent and are associated with adverse effects [8]. Total contamination rate of mentioned PCBs is an indicator of contamination with PCBs. Additionally, the sum of these six PCBs accounts for 50% of the total NDL-congeners in food (European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) [9].

Due to their aromatic and hydrophobic structure, these compounds have different functions, which are categorized in terms of these functions. One of the broadest categorizations is based on the PCB backbone and clusters. Dioxin-like (DL) compounds can bind to some endocrine receptors and mimic from the organic ligands and hormones such as Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and testosterone receptor (TR) [10]. DL compounds are classified into toxic and anti-estrogenic congeners. The attachment of these congeners to endocrine receptors can induce the activity of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP) enzymes. Therefore, these compounds can be called endocrine disturbing chemicals (EDC) [11].

The endocrine distribution is one of the main causes of malignancies in related organs such as ovary, breast, and prostate. The main regulating effect of PCBs in the endocrine system is related to the AhR system [12]. The AhR activation might be led to overexpression of organophosphate hydrolyzing enzymes such as paraoxonase/aryl esterase (PON1). The expression of PON1 gene would be dysregulated in malignant cells and AhR overexpression may cause an increase in malignancy by out-of-control cell proliferation [13]. The in vitro study of PCBs may be very informative to evaluate the toxic, oncogenic, and protective functions of these compounds. Hormone responsive cells are the best candidates for these studies. Some malignant cell lines such as MCF7 (ER+, PR+, AhR+), LNCap (TR+, AhR+), and MDA-MB-231 (hormone-independent cell line) [14] are positively expressing AhR and the response of PCB exposure can be evaluated by cell viability and PON1 expression assays.

Nonetheless, to our knowledge, how MCF7, LNCap, and MDA-MB-231 lines response to different PCBs is still unclear. Hence, this study aimed to investigate the effect of different concentrations of PBCs on the viability of these lines, the expression of PON1 gene as well as the interaction of PBCs with the receptor. This study indicated that the PCB compounds could affect the cell viability and the expression of PON1 gene in malignant cells. The findings revealed that these compounds would be ineffective in cells negatively hormone receptors such as ER. Molecular docking proved that PCBs could strongly bind to the AhR receptor on the surface of cells and then activate innate host responses. It should also be noted that, cell lines choices are limited due to the fact that the selected cell lines must be hormone-dependent and have an AhR receptor.

Experimental

Study design

This study was designed to investigate the effect of PCBs on cell proliferation and gene expression. MCF-7 cell, MDA-MB231, and LNCap cells were treated with different concentrations (0.001–100 μM) of six types of PCBs to evaluate cell proliferation. The most effective concentration of each PCB was selected for the expression analysis of PON1 gene.

Cell culture

MCF7 as a breast adenocarcinoma cell line expressing ER, PR, and AhR, MDA-MB231 as a basal-like triple-negative breast cancer cell line expressing AhR, and LNcap as an androgen-sensitive human prostate adenocarcinoma cell were purchased from Pasteur institute cell bank and cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 85% humidity incubator. The conditioned media for MCF7 was Glutamax added RPMI-1640 containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) [Gibco-USA], 1% penicillin-streptomycin [Gibco-USA]. LNcap and MDA-MB231 were cultured with high glucose Glutamax added Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) [Gibco-USA] containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. After cell density reached up to 70% in cell culture flasks, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered sodium (PBS) (Sigma-Germany) and then were detached using 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA solution [Gibco-USA]. 1 × 104 cells were seeded in 96-well plates for MTT assay and 1 × 106 cells were seeded in 6-well plates for gene expression analysis.

PCB compounds preparation and treatment

PCB compounds, including 2,4,4′-Trichlorobiphenyl (PCB 28), 2,2′,5,5’-Tetrachlorobiphenyl (PCB 52), 2,2′,4,5,5′-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 101), 2,2′,3,4,4′,5′-hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 138), 2,2′,4,4′,5,5′-hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 153), and 2,2′,3,4,4′,5,5’-Heptachlorobipheny (PCB 180) were purchased from Dr. Ehrenstorfer Reference Materials (Augsburg, Germany). An amount of 10 mg of each compound was dissolved in 10 ml of 1 N n-hexane (Merck-Germany) with a final concentration of 1 mg/ml per standard. According to the molecular weight of each PCB, a concentration of 1 M was prepared from each standard. Afterwards, concentrations of 100, 10, 1, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 μM of each standard were used for analysis.

MTT assay

Briefly, 20 h after cell seeding, the media was replaced with treatment media containing solubilized compounds of PCB, and cells were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 85% humidity incubator (the treatments were repeated 6 times). After 48 h, 20 μl of 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT solution) was added in per well and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 85% humidity incubator for 5 h. The supernatant was removed from wells and 100 μl DMSO was added to solve formazan sediments. The plates were read at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer device. The cell viability percentage was calculated using this formula: CV% = [mean of treated wells OD/mean of non-treated wells OD] ×100.

Quantitative real-time PCR

The cell lines were seeded onto 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well and incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator for 48 h. After exposure the most effective concentration of six PCBs for 48 h, cells were trypsinized and centrifuged at 3000 rpm, 4 °C for 5 min. Total mRNA was extracted from the pellet using RNA extraction Trizol reagent (Sigma-Germany) according to the supplier’s instructions. The quantity and purity of RNA were determined by optical density measurements at OD A260/A280 ratio with 1.8 or above using Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). The integrity of RNA was confirmed by running 0.5 μg of RNA samples on 1% agarose gel. Later, cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of the total RNA using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., MA, USA) as instructed by the manufacturer and stored at −20 °C until assay. Real-time PCR was performed in a total volume of 20 μL in the ABI real-time PCR equipment (AB Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) using a GreenStar Master Mix (Amplicon, Denmark). The 20 μL Real-time PCR reaction mixture contained 20 ng cDNA template, 10 μL of 2X GreenStar master mix, 200 nM of forward and reverse primers, and PCR-grade water. β-Actin was used as a reference gene. The sequences of the primers for the qRT-PCR are as follows: PON1 Forward: CTGAGCACTTTTATGGCACAAATGA and Revers: ACCACGCTAAACCCAAATACATCTC derived from a previously published study [15].; β-actin: sense, 5′-TGCAGAGGATGATTGCTGAC-3′; antisense, 5′-GAGGACTCCAGCCACAAAGA-3′. The reaction was performed in the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the PCR cycling conditions as follows: 3 min enzyme activation at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 3 s initial denaturation at 95 °C, and annealing/extension at 58 °C for 32 s. Melting curve analysis was performed to verify the specificity of each primer after PCR to ensure amplification specificity. The threshold cycle (Ct) number was determined and used in the comparative Ct method. The folding change of the mRNA level in all groups was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT formula.

Molecular docking

In this study, docking of six PCBs against AhR was performed using Molegro Virtual Docker V 6.0 (MVD) software. A single rigid crystal structure of a protein was used for docking studies from the 32 crystal structures of AhR available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (5Y7Y) [16], accessed at the URL (http://www.rscb.org/pdb) under the criteria that they had reasonable resolution (≤ 2.4 Å) and involved the non-mutated AhR from Homo sapiens, in the complex with small-molecule ligands. Six PCB (PCB 28, PCB 52, PCB 101, PCB 138, PCB 153, and PCB 180 were docked against AhR crystal structure and 1000 independent runs were performed with the guided differential evolution algorithm, with each of these docking runs returning one solution (pose). The Moldock scoring function used by MVD was derived from the PLP scoring functions originally proposed by Naeem et al. The 10 solutions obtained from the 1000 independent docking runs were re-ranked, in order to further increase the docking accuracy, by using a more complex scoring function. In the MVD, along with the docking scoring terms, a Lennard Jones 12–6 potential and sp2-sp2 torsion terms were also used [17]. Based on the pilot docking studies, the MolDock rerank scores were selected for ranking the obtained poses, and for all the AhR docking performed here, the poses selected as the best were taken as those with the highest MolDock re-rank score. The AhR crystal structure was directly downloaded to the workspace of MVD from the PDB accessed at the URL: (http://www.rscb.org/pdb). The structure of PCB compounds was drawn on ChemBioDrawUltra 12.0 software and imported to the MVD workspace in ‘sdf’ format. All necessary valency checks and H atom addition were thus performed using the utilities provided in MVD. The binding site specifies the region of interest where the docking procedure will look for promising poses (ligand conformations).

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard error (SEM) of at least three tests done in duplicates. The relative expression of PON1 gene was determined using the 2-ΔΔCт method. 2-ΔΔCт was compared for each treated group with the control groups using SPSS 25 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill, USA) for ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05) was used to compare the mean values of groups. (Descriptive results are expressed as mean ± SD. evaluation of normality of the data was performed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Homogeneity of variance was measured by Levine’s test).

Results

Effect of PCBs on MCF7 cell viability

The results of MTT assay for MCF-7 cells exposed to the different concentrations of PBCs are shown in (Fig. 1). Accordingly, the viability of MCF-7 cells was significantly affected by the different concentrations of PBCs (P < 0.05). The application of different concentrations of PCB 28 caused significant changes in the viability of cells (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Effect of different concentrations of PCB 28 (a), PCB 52 (b), PCB 101 (c), PCB 138 (d), PCB 153 (e), and PCB 180 (f) on viability of MCF-7 cells. Values represent means ± SD (n = 6). Different lowercase letters on error bars imply significant differences among groups (P < 0.05). Non-identical letters indicate a statistically significant difference at the level of p ≤ 0.05

The viability of cells treated with 0.001 and 100 μM of PCB 28 was lower than that in the control group (Fig. 1a). This PCB at 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 μM significantly increased the cell viability compared with the control. At all the concentrations of PCB 52, the viability of cells was significantly decreased compared with the control group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1b). The lowest viability was observed in the cells treated with 10 μM of PCB 52. The MCF-7 cells differently responded to the increasing concentrations of PCB 101 (Fig. 1c). The lowest and the highest viability were recorded in the cells exposed to 0.001 μM and 1 μM, respectively. The results showed that the viability of MCF-7 cells was depended on the concentration of PCB.

There were significant changes in the viability of MCF-7 cells exposed to the different concentrations of PCB 138 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1d). Compared with the control, the viability of 0.001 μM–treated cells were markedly reduced. However, with increasing the concentration of PCB 138 from 0.001 to 1 μM the cell viability was gradually increased. At the concentrations higher than 1 μM, the viability of cells began to decrease although it was not significantly lower than the control. While PCB 153 at 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 μM concentrations reduced the viability of MCF-7 cells, it had a positive effect on the viability of cells at 1, 10, and 100 μM. As shown in Fig. 1f, all the applied concentrations of PCB 180 significantly enhanced the viability of MCF-7 cells (P < 0.05). The highest viability was observed in the cells exposed to 100 μM of this PCB.

Effect of PCBs on LNCap cell viability

The response of LNCap cells to different concentrations of PCBs was varied depending on the type and concentration of these compounds (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of different concentrations of PCB 28 (a), PCB 52 (b), PCB 101 (c), PCB 138 (d), PCB 153 (e), and PCB 180 (f) on viability of LNCap cells. Values represent means ± SD (n = 6). Different lowercase letters on error bars imply significant differences among groups (P < 0.05). Non-identical letters indicate a statistically significant difference at the level of p ≤ 0.05

All the applied concentrations of PCB 28 significantly increased the viability of cells as compared with the non-treated group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2a). While the cells treated with 100 μM showed a significant decrease, significant changes in the viability of cells treated with 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 μM of PCB 52 were not observed (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2b). Similar results were observed for PCB 101(Fig. 2c) and PCB -138 (Fig. 2d). As shown in (Fig. 2e), the effects of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 μM concentrations of PCB 153 were significantly more pronounced on the viability of LNCap cells than 100 μM (P < 0.05). The viability of cells exposed to PCB 180 was significantly increased at all the concentrations except 1 μM (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2e).

Effect of PCBs on MDA-MB-231 cell viability

The results of MTT assay for MDA-MB-231 cells treated with different concentrations of the examined PCBs (PCB 28, PCB 52, PCB 101, PCB 138, PCB 153, and PCB 180) showed that the viability of these cells was not significantly affected by the PCBs (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of different concentrations of PCB 28 (a), PCB 52 (b), PCB 101 (c), PCB 138 (d), PCB 153 (e), and PCB 180 (f) on viability of MDA-MB-231 cells. Values represent means ± SD (n = 6). Different lowercase letters on error bars imply significant differences among groups (P < 0.05). Non-identical letters indicate a statistically significant difference at the level of p ≤ 0.05

Gene expression analysis

The most effective concentration of each treatment which could enhance the CV% of examined cell lines was chosen for expression analysis of PON1 gene. MCF7: 0.1 μM for PCB 28, 100 μM for PCB 52, 1 μM for PCB 101, 1 μM for PCB 138, 100 μM for PCB 153 and PCB 180. LNCap: 0.001 μM for PCB 28, 0.01 μM for PCB 52, 0.1 μM for PCB 101, 0.01 μM for PCB 138, 1 μM for PCB 153 and 100 μM for PCB 180. Since all concentrations of each type of PCBs had the same effect on the cell viability status of MDA-MB-231, the highest dose of each treatment was chosen.

The real-time PCR results for PON1 gene from these cell lines are shown in (Fig. 4). The expression level of PON1 gene in the MCF7 cells treated with PCB 101 and PCB -28 was significantly higher than other groups (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4a). There was no significant difference among the cells treated with PCB 52, PCB 138, PCB 153, and PCB 180. According to the obtained results, the expression level of PON1 gene was significantly upregulated in the LNCap cells treated with PCB 28 and PCB 101 compared with those treated with PCB 52, PCB 138, PCB 153, and PCB 180 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4b). Similar to the MCF7 cells, the LNCap cells treated with PCB 52, PCB 138, PCB 153, and PCB 180 had not significant differences. As shown in (Fig. 4c), the expression level of PON1 gene in the MDA-MB-231 cells was not significantly affected by any of the PCBs (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Relative expression analysis of PON1 gene in MCF-7 (a), LNCap (b), and MDA-MB-231 (c) cells after treatment with the optimum dose of PCBs (PCB 28, 100 μM; PCB 52, 0.1 μM; PCB 101, 100 μM; PCB 138, 1 μM; PCB 153, 0.01 μM; PCB 180, 1 μM). Values represent means ± SD (n = 3). Different lowercase letters on error bars imply significant differences among groups (P < 0.05). Non-identical letters indicate a statistically significant difference at the level of p ≤ 0.05. beta actin was used as a house-keeping gene and normalize the data

Molecular docking analysis

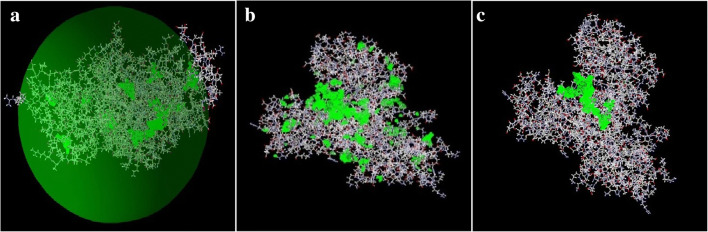

Docking process, the interaction and binding of ligands-protein was done and visualized using Molegro Virtual Docking (MVD). MVD automatically identifies potential binding sites (also referred to as cavities or active sites) by using its cavity detection algorithm. The cavities within a cube centered at the experimentally known ligand position were used (Fig. 5a). The properties of this box were as follows: X = −5.02, Y = 34.96, Z = 9.32, and R = 38 Å. The cavities identified by the cavity detection algorithm were then used by the guided differential evolution search algorithm to focus the search, to that specific area during the docking simulation. In the case of the crystal structures for AhR complexes, the program generally identified 100 different binding sites (Fig. 5b). The best cavity position with score of 99.99% hosting PCBs was selected for consideration, as it includes the bound ligand (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Hypothetical box contains all the predicted cavities for binding of ligand (PCB) to receptor (AhR), (a). The 100 cavity MVD-detected cavities in AhR (PDB code 5Y7Y [15], (b). The best cavity position with score 99.99% hosting PCBs, (c). Detected cavity is green; carbon atoms are grey; oxygen atoms are red; nitrogen atoms are blue

Docking of six ligands, PCB 28, PCB 52, PCB 101, PCB 138, PCB 153, and PCB 180 was performed with the crystal structure of AhR and each ligand was chosen the best position to determine the re-rank score. In each docking run, the best poses were selected based on their MVD re-rank scores, and the mean of the 5 re-rank scores was then computed as the final score for each compound. The MVD score and the re-rank scores of the best poses for each of the docking studies of PCBs ligands with AhR are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interaction rate of PCBs with AhR receptor

| Interactions | MolDock Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB28 | PCB52 | PCB101 | PCB138 | PCB153 | PCB180 | ||

| External Ligand Interactions | Steric (by PLP) | −88.645 | −76.754 | −94.204 | −81.300 | −83.329 | −85.943 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Electrostatic (short range) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Electrostatic (long range) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Water-Ligand Interactions | −0.238 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Total External interactions | −88.883 | −76.754 | −94.204 | −81.300 | −83.329 | −85.943 | |

| Internal Ligand Interactions | Torsional strain | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Steric (by PLP) | 9.798 | 7.729 | 6.258 | 7.162 | 6.257 | 14.760 | |

| Hydrogen bonds | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Electrostatic | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Total Internal interactions | 9.798 | 7.729 | 6.258 | 7.162 | 6.257 | 14.760 | |

| Total interactions | −79.085 | −69.026 | −87.946 | −74.139 | −77.072 | −71.183 | |

The results revealed that among all interactions (external ligand interactions), the ligands had Protein-Ligand Interactions Steric (by PLP) with the receptor (Table 1). It should be noted that a more negative score indicates more effective interaction. Accordingly, PCB 101 had the strongest interaction with the receptor compared with others. On the other hand, PCB 52 had the weakest interaction with the receptor. The values of total interactions showed that all PCBs had a strong interaction with the AhR receptor. The strongest and weakest interactions were recorded for PCB 180 and PCB 52, respectively.

The interaction of amino acids involved in the steric interaction with ligand as Moldock (MD) score is shown in Table 2. It should be noted that a more negative score indicates that the interaction was more effective. Scores lower than −5 mean that the interaction was strong. Therefore, the lower scores indicate better interaction. The top amino acids involved in the steric interaction with the different PCBs were as follows: PCB 28, Gln 245, Thr 222, Glu 362, Cys 224, Arg 223, Gly 246, Lys 247, Leu 343, and Asp 173; PCB 52, Leu 169, Asp 173, Pro 195, Glu 170, Ser 192, and Val 196; PCB 101, Lys 249, Gln 207, Leu 221, Ser 218, Phe 250, Lys 247, Leu 248, and Thr 215; PCB 138, Leu 169, Asp 173, Pro 195, His 166, Val 196, and Glu 170; PCB 153, Gln 245, Thr 222, Asp 173, Ala 172, Lys 247, Leu 343, and Arg 342; PCB 180, Lys 247, Lys 249, Pro 214, Ser 218, and Leu 221.

Table 2.

Amino acids involved in the steric interaction of PCBs (ligand) with AhR receptor

| PCB28 | PCB52 | PCB101 | PCB138 | PCB153 | PCB180 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue | MD Score | Residue | MD Score | Residue | MD Score | Residue | MD Score | Residue | MD Score | Residue | MD Score |

| Gln 245 | −11.063 | Leu 169 | −17.577 | Lys 249 | −17.1956 | Leu 169 | −18.7533 | Gln 245 | −14.9837 | Lys 247 | −19.544 |

| Thr 222 | −10.8284 | Asp 173 | −15.2108 | Gln 207 | −11.8992 | Asp 173 | −14.2827 | Thr 222 | −10.7338 | Lys 249 | −12.5024 |

| Glu 362 | −10.7393 | Pro 195 | −10.4178 | Leu 221 | −8.93262 | Pro 195 | −11.7464 | Asp 173 | −10.5746 | Pro 214 | −9.48645 |

| Cys 224 | −10.2023 | Glu 170 | −7.47749 | Ser 218 | −8.68353 | His 166 | −9.15472 | Ala 172 | −7.4432 | Ser 218 | −9.44121 |

| Arg 223 | −8.5883 | Ser 192 | −6.8158 | Phe 250 | −8.18874 | Val 196 | −8.23298 | Lys 247 | −7.38107 | Leu 221 | −9.22697 |

| Gly 246 | −8.27098 | Val 196 | −6.37435 | Lys 247 | −6.64127 | Glu 170 | −5.35839 | Leu 343 | −7.22299 | Asp 173 | −4.96356 |

| Lys 247 | −5.40022 | Gly 174 | −4.88122 | Leu 248 | −6.16904 | Gly 174 | −4.40044 | Arg 342 | −5.71903 | Thr 222 | −4.89468 |

| Leu 343 | −5.33689 | Ala 172 | −2.79212 | Thr 215 | −5.50378 | Ser 192 | −3.51482 | Ala 171 | −4.33789 | Thr 215 | −3.9044 |

| Asp 173 | −5.01434 | His 166 | −1.94371 | Pro 214 | −4.93845 | Ala 172 | −2.49491 | Gly 246 | −3.29301 | Leu 248 | −3.50152 |

| Thr 361 | −4.4191 | Lys 165 | −0.30577 | Leu 203 | −3.54112 | Lys 165 | −1.42441 | Glu 362 | −2.798 | Ala 219 | −2.50232 |

| Pro 360 | −3.29906 | – | – | Tyr 217 | −2.95386 | – | – | Arg 223 | −2.47588 | Gln 207 | −0.8578 |

| Gln 359 | −2.76077 | – | – | Thr 222 | −2.4918 | – | – | Ser 218 | −0.5003 | Tyr 217 | −0.32845 |

| Ala 172 | −2.04648 | – | – | Phe 252 | −0.8292 | – | – | Ala 219 | −0.4583 | Leu 268 | −0.30469 |

| Arg 342 | −0.69449 | – | – | Leu 204 | −0.73218 | – | – | Thr 361 | −0.4245 | Glu 362 | −0.30195 |

| Ala 171 | 2.53216 | – | – | Leu 268 | −0.71856 | – | – | Ile 273 | −0.3295 | – | – |

| – | – | – | – | Ala 219 | −0.44886 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

The mode of binding (steric interaction) of different PCBs to the active site of AhR receptor is shown in (Fig. 6). As can be seen, the secondary structure of AhR receptor when the examined PCBs were bound to the active state was different. Due to the importance of the type of amino acids involved in the interaction of receptor-ligand complex, the interaction of amino acids of AhR receptor with PCBs is shown in (Fig. 7). The amino acids involved in the steric interaction of AhR receptor with different PCBs were as follows: PCB 28, Arg 342, Pro 360, Glu 362, Ala 172, Lys 247, Asp 173, Ala 171, and Gln 245; PCB 52, Glu 170, Val 196, Ser 192, and Leu 169; PCB 101, Lys 247, Thr 215, Phe 250, Ser 218, Lys 249, and Leu 221; PCB 138, Glu 170, Leu 169, and Ser 192; PCB 153, Arg 342, Glu 362, Gln 245, Lys 247, Leu 343, Asp 173, and Gly 246; PCB 180, Lys 247, Lys 249, Ser 218, and Leu 248.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of steric interaction of AhR receptor with PCB 28 (a), PCB 52 (b), PCB 101 (c), PCB 138 (d), PCB 153 (e), PCB 180 (f). The α helices and β strands are represented as coils (red) and arrows (blue), respectively. PCBs are represented in ball and stick (green)

Fig. 7.

Steric interaction of amino acids (residues) of AhR receptor with PCB 28 (a), PCB 52 (b), PCB 101 (c), PCB 138 (d), PCB 153 (e), PCB 180 (f)

Discussion

The wide range of toxic effects of PCBs depends on the chemical properties number, and position of chlorines. The six, compounds of PCBs (28, 52, 101, 138, 153, and 180) mentioned in this study have been studied and their toxicity has been expressed through the affinity for binding to an Ah receptor. However, the larger NDL class has only been studied in recent years, and it is suggested that researchers pay attention to this issue to determine the true role of PCBs in toxicological evaluation. The data published in this study have caused differences in the behavior of PCBs due to significant variation in factors such as the number and position of chlorinated compounds, doses and cell lines. Considering the importance of PCBs in food and the risks involved, we chose these six, compounds that have the highest amount in the environment, and the foods. The second factor is very important because food is the main source of PCBs for humans, especially in fish, oysters, milk and dairy products. In this study, we selected three cell lines (MCF7, LNCap, and MDA-MB-231) that have been widely used for cytotoxicity testing and viability by using the MTT. In addition, the effective concentrations of PCBs were used for expression analysis of PON1 gene. The results can indicate the molecular effect of PCB forms. PCBs have previously been shown to increase the proliferation potential of MCF-7 cells [18]. Our results showed that the response of cells to PCBs is dependent on cell type, as well as on the type and concentration of PCB. This data is consistent with the results of Endo et al. [19] and Radice et al. [20].

The study of the effect of PCBs on cancer cell lines can be informative in understanding the carcinogenic mechanism of these congeners [21]. These compounds bind to the AhR receptor and can disturb the endocrine pathway PCBs; especially non-coplanar PCBs mimic the estrogen-like hormones and in hormone-responsive cells can induce cell proliferation or apoptosis through many different pathways. The PCBs effects on malignant cells have been widely studied in previous studies [22]. Dutta et al. [23] in a study using large-scale microarray assays and network analysis showed that the expression level of PON1 as an antioxidant agent could be changed under PCB exposure.

In a study by Radice et al. it was found that the proliferation or anti-apoptosis induction after PCB treatment is stimulated via mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) ERK1/2 signaling pathway, which might be occurred in PCB 153 earlier than others so it cannot be detected in the same condition of other treatments [20]. Therefore, it is suggested that the effect of treatment with PCB 101 and 153 can be performed in a shorter period of time. Burow et al. showed that the PCBs have a suppressive impact on TNF-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells (ER-positive) but not in MDA-MB-231 (ER-negative) cells. This confirmed our findings regarding the MDA-MB231 cells, in which the different treatments of PCBs could not affect the viability of them. These results can be explained in the case of ER expression status and its relationship with DL-PCB congener effect [24]. However, it has been shown that the ortho-substituted PCBs can impact on cytochrome P450 [25] and increase the metastatic behavior of cells by activating Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) system [26].

The results of gene expression analysis in the present work showed that PCB exposure altered the mRNA level of PON1 in the cells. The highest expression of PON1 was found in the cells treated with PCB 101. Leijs et al. [27] indicated that PCB 180 can cause significant upregulation of some genes related to NF-kB functioning. Activation of the NF-kB pathway can modulate the AhR activation status [28]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous study about the effect of PCB101 on the expression of PON1. However, the microarray analyses indicated that its effect on gene expression is more than other PCBs [27].

Meanwhile, in order to explore the potential mechanisms of PCBs effects on cells, the molecular docking of these compounds was carried out on the active site of the AhR receptor. The analysis of ligand-receptor interactions showed that the steric interactions are mainly responsible for the binding of PCBs in the active site of AhR receptor. The data suggest that the interaction of PCBs with AhR receptor could be modulated by steric interactions. Based on the molecular docking information, the different amino acids have potentially important roles in the binding and interaction of PCBs and AhR receptor. To our knowledge, this is the first study of how different PCBs bind and subsequently activate the AhR receptor. The obtained results can help to understand the binding process and provide a detailed characterization of the molecular mechanisms responsible for the effects of PCBs on the cells.

Conclusion

For the first time, this study indicated that the PCB compounds could affect the cell viability and the expression of PON1 gene in malignant cells. The findings revealed that these compounds would be ineffective in cells negatively expressing hormone receptors such as ER and can increase the expression of the PON1 gene, which has a negative effect on the growth of children. Molecular docking proved that PCBs could strongly bind to the AhR receptor on the surface of cells and then activate innate host responses. However, more mechanistic studies are necessary to clarify the exact mechanism of action of PCBs and the biochemical interactions between these compounds and other agents. Since the contamination and concentration of PCBs are very important in daily general food, the evaluation of their values in industrial and natural foods should be carefully considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mahdi Taherian and Dr. Hassan Noor-Bazargan for their constructive comments on our manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by [Fatemeh Yazdi], [Akram Eidi] and [Shahram Shoeibi]. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [Fatemeh Yazdi] and revised by [Mohammad Hossein Yazdi] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no potential for competing for financial or other interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fatemeh Yazdi, Email: Fatemeh.yazdi@yahoo.com.

Shahram Shoeibi, Email: sh.shoeibi@fda.gov.ir.

Mohammad Hossein Yazdi, Email: mh-yazdi@tums.ac.ir.

Akram Eidi, Email: akram_eidi@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Wen Y, Schoups G, van de Giesen N. Organic pollution of rivers: combined threats of urbanization, livestock farming and global climate change. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–9. 10.1038/srep43289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Dhakal K, Gadupudi GS, Lehmler HJ, Ludewig G, Duffel MW, Robertson LW. Sources and toxicities of phenolic polychlorinated biphenyls (OH-PCBs) Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25:16277–16290. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9694-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crinnion WJ. Polychlorinated biphenyls: persistent pollutants with immunological, neurological, and endocrinological consequences. Altern Med Rev. 2011;16(1):5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jayaraj R, Megha P, Sreedev P. Organochlorine pesticides, their toxic effects on living organisms and their fate in the environment. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2016;9:90–100. doi: 10.1515/intox-2016-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roszko M, Jedrzejczak R, Szymczyk K. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polychlorinated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and organochlorine pesticides in selected cereals available on the polish retail market. Sci Total Environ. 2014;466-467:136–151. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chovancova J, Conka K, Kocan A, Sejakova ZS. PCDD, PCDF, PCB and PBDE concentrations in breast milk of mothers residing in selected areas of Slovakia. Chemosphere. 2011;83:1383–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh WX, Hornbuckle KC, Wang K, Thorne PS. Serum polychlorinated biphenyls and their hydroxylated metabolites are associated with demographic and behavioral factors in children and mothers. Environ Int. 2016;94:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brazova T, Hanzelova V, Miklisova D. Bioaccumulation of six PCB indicator congeners in a heavily polluted water reservoir in eastern Slovakia: tissue-specific distribution in fish and their parasites. J Parasitol Res. 2012;111:779–786. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2900-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Opinion of the scientific panel on contaminants in the food chain on a request from the commission related to the presence of non-dioxin like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) in feed and food. EFSA J. 2005;3:1–137. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vondracek J, Machala M, Bryja V, Chramostova K, Krcmar P, Dietrich C, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-activating polychlorinated biphenyls and their hydroxylated metabolites induce cell proliferation in contact-inhibited rat liver epithelial cells. Toxicol Sci. 2005;83:53–63. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, Zoeller RT, Gore AC. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2009;2005:293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolluri SK, Jin UH, Safe S. Role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in carcinogenesis and potential as an anti-cancer drug target. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91:2497–2513. doi: 10.1007/s00204-017-1981-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dietrich C. Antioxidant functions of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2016/7943495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vázquez SM, Mladovan A, Garbovesky C, Baldi A, Lüthy IA. Three novel hormone-responsive cell lines derived from primary human breast carcinomas: functional characterization. J Cell Physiol. 2004;199:460–469. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turgut Cosan D, Colak E, Saydam F, Yazıcı H, Degirmenci I, Birdane A, et al. Association of paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene polymorphisms and concentration with essential hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2016;38:602–607. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2016.1174255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakurai S, Shimizu T, Ohto UJJo BC. The crystal structure of the AhRR–ARNT heterodimer reveals the structural basis of the repression of AhR-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:17609–17616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.812974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naeem S, Hylands P, Barlow D. Docking studies of chlorogenic acid against aldose redutcase by using molgro virtual docker software. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2013;3(1):13. 10.7324/JAPS.2013.30104.

- 18.Ptak A, Mazur K, Gregoraszczuk EL. Comparison of combinatory effects of PCBs (118, 138, 153 and 180) with 17 beta-estradiol on proliferation and apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Toxicol Ind Health. 2011;27:315–321. doi: 10.1177/0748233710387003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Endo F, Monsees TK, Akaza H, Schill W-B, Pflieger-Bruss S. Effects of single non-ortho, mono-ortho, and di-ortho chlorinated biphenyls on cell functions and proliferation of the human prostatic carcinoma cell line, LNCaP. Reprod Toxicol. 2003;17:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(02)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radice S, Chiesara E, Fucile S, Marabini L. Different effects of PCB101, PCB118, PCB138 and PCB153 alone or mixed in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:2561–2567. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robertson LW, Ludewig G. Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) carcinogenicity with special emphasis on airborne PCBs. Gefahrst Reinhalt Luft. 2011;71(1–2):25–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milon A, Opydo-Chanek M, Tworzydlo W, Galas J, Pardyak L, Kaminska A, Ptak A, Kotula-Balak M. Chlorinated biphenyls effect on estrogen-related receptor expression, steroid secretion, mitochondria ultrastructure but not on mitochondrial membrane potential in Leydig cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;369:429–444. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2596-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dutta SK, Mitra PS, Ghosh S, Zang S, Sonneborn D, Hertz-Picciotto I, Trnovec T, Palkovicova L, Sovcikova E, Ghimbovschi S, Hoffman EP. Differential gene expression and a functional analysis of PCB-exposed children: understanding disease and disorder development. Environ Int. 2012;40:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burow ME, Tang Y, Collins-Burow BM, Krajewski S, Reed JC, JA ML, et al. Effects of environmental estrogens on tumor necrosis factor α-mediated apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20(11):2057–2061. 10.1093/carcin/20.11.2057. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Spink BC, Pang S, Pentecost BT, Spink DC. Induction of cytochrome P450 1B1 in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells by non-ortho-substituted polychlorinated biphenyls. Toxicol in Vitro. 2002;16:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(02)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu S, Li S, Du Y. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) enhance metastatic properties of breast Cancer cells by activating rho-associated kinase (ROCK) PLoS One. 2010;5:e11272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leijs MM, Gan L, De Boever P, Esser A, Amann PM, Ziegler P, et al. Altered gene expression in dioxin-like and non-dioxin-like PCB exposed peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(12):2090. 10.3390/ijerph16122090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Champion S, Sauzet C, Bremond P, Benbrahim K, Abraldes J, Seree E, Barra Y, Villard PH. Activation of the NF kappa B pathway enhances AhR expression in intestinal Caco-2 cells. ISRN Toxicol. 2013;2013:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2013/792452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]