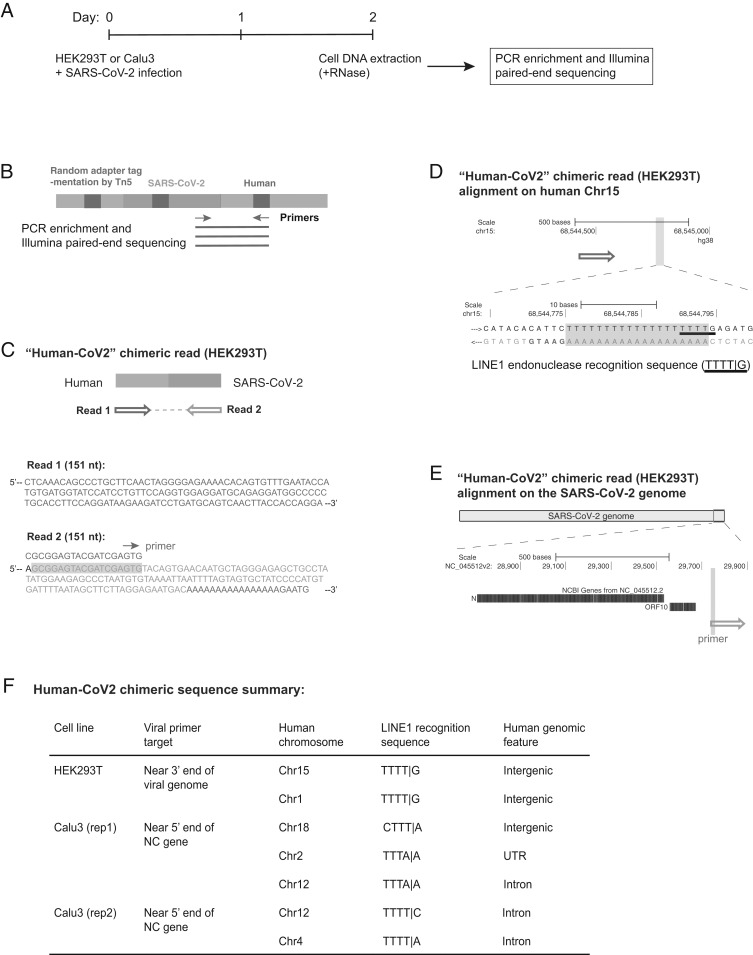

Fig. 2.

Evidence for integration of SARS-CoV-2 cDNA in cultured cells that do not overexpress a reverse transcriptase. (A) Experimental workflow. (B) Experimental design for the Tn5 tagmentation-mediated enrichment sequencing method used to map integration sites in the host cell genome. (C) A human–viral chimeric read pair supporting viral integration. The reads are aligned with the human (blue) and SARS-CoV-2 (magenta) genomic sequences. The arrows indicate the read orientations relative to the human and SARS-CoV-2 genomes as shown in D and E. Sequence of the viral primer used for enrichment is shown with green highlight in the read (corresponding to the green arrow illustrated in B). Sequences that could be mapped to both genomes are shown in purple. (D) Alignment of the read pair in C with the human genome (chromosome 15, blue arrow). The highlighted (light blue) region of the human sequence is enlarged to show the LINE1 recognition sequence (underlined) with a 19-base poly-dT sequence (purple highlight) that could be annealed by the viral poly-A tail for “target-primed reverse transcription.” Additional 5-bp human sequence (GAATG, blue) was captured in read 2 (C), supporting a bona fide integration site. (E) Alignment of the read pair in C with the SARS-CoV-2 genome (magenta). The viral primer sequence is shown with green highlight. (F) Summary of seven human–viral chimeric sequences identified by the enrichment sequencing method in the two cell lines showing the integrated human chromosomes, LINE1 recognition sequences close to the chimeric junction, and human genomic features at the read junction.