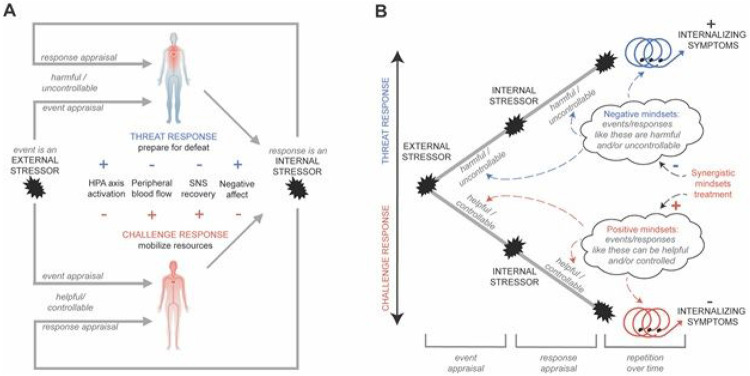

Figure 1.

The model guiding the present study’s predictions. (A) In an acute situation, differences in appraisals lead to differences in challenge versus threat responses. (B) Mindsets lead to differences in appraisals and shape responses in acute situations and across situations over time. In the event appraisal stage, stressors are appraised as harmful/uncontrollable or more helpful/controllable, cultivating threat or challenge response tendencies, respectively. Then, at the response appraisal stage, when individuals actively engage with stressors, the meaning of their stress response is appraised as either distressing and non-functional (harmful/uncontrollable) or as a resource that helps one address situational demands (helpful/controllable), resulting in further threat or challenge type stress responses, respectively. As shown in Panel A, challenge and threat responses differentially activate stress axes in the brain. Although both elicit sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) activation, threat also stimulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the end-product of which is the catabolic adrenal hormone cortisol, in anticipation of damage or social defeat. Challenge is characterized by increased peripheral blood flow (which is why it is depicted in red), and an agile response onset/offset: resources are mobilized rapidly, and individuals return to homeostasis quickly after stress offset. Threat, however, results in increased vascular resistance and less oxygenated blood flow to the periphery (which is why it is depicted in blue) as HPA activation tempers SAM effects and produces a more prolonged stress response than challenge due to the longer half-life of cortisol compared to anabolic hormones. Challenge and threat then have different consequences for motivation and affective responses. Whereas threat leads to avoidance motivation and negative affect, challenge elicits approach motivation and more positive affect relative to threat. As shown in (B) mindsets are situation-general beliefs about categories of events (e.g., academic stressors) and responses (e.g., feelings of worry). The mindsets shape appraisals at the event stage and next at the response stage. Thus, mindsets “count twice” toward the construction of affective responses. Downstream, if individuals respond with an optimized challenge type stress response, this increases the likelihood they will engage with and respond to future stressors more adaptively in a self-reinforcing, positive feedback cycle, the end result of which is buffering against internalizing symptoms (bottom right in panel B).