Abstract

Recently, a new ECG criterion, the Peguero-Lo Presti (PLP), improved overall accuracy in the diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)—compared to traditional ECG criteria, but with few patients with advanced age. We analyzed patients with older age and examined which ECG criteria would have better overall performance. A total of 592 patients were included (83.1% with hypertension, mean age of 77.5 years) and the PLP criterion was compared against Cornell voltage (CV), Sokolow-Lyon voltage (SL) and Romhilt-Estes criteria (cutoffs of 4 and 5 points, RE4 and RE5, respectively) using LVH defined by the echocardiogram as the gold standard. The PLP had higher AUC than the CV, RE and SL (respectively, 0.70 vs 0.66 vs 0.64 vs 0.67), increased sensitivity compared with the SL, CV and RE5 (respectively, 51.9% [95% CI 45.4–58.3%] vs 28.2% [95% CI 22.6–34.4%], p < 0.0001; vs 35.3% [95% CI 29.2–41.7%], p < 0.0001; vs 44.4% [95% CI 38.0–50.9%], p = 0.042), highest F1 score (58.3%) and net benefit for most of the 20–60% threshold range in the decision curve analysis. Overall, despite the best diagnostic performance in older patients, the PLP criterion cannot rule out LVH consistently but can potentially be used to guide clinical decision for echocardiogram ordering in low-resource settings.

Subject terms: Cardiology, Hypertension

Introduction

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is an independent predictor of mortality, and cardiovascular morbidity in hypertensive individuals1–5. LVH is a marker of poor prognosis also in elderly patients, although few data are available in this population6. The 12-lead ECG is recommended as a universal screening of LVH for patients with hypertension according to international guidelines7,8. ECG is accessible worldwide, inexpensive and has established its prognostic capacity9. Also, the addition of the ECG-based LVH criteria to common cardiovascular risk scores can increase the prediction performance of such scores10,11. However, the diagnosis of LVH by the ECG has some limitations, namely the great number of available criteria12,13 and poor sensitivity (4–48%) when compared to echocardiogram and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)13–16. Additionally, extra cardiac factors can mitigate the depolarization vector (such as body habitus, weight, pericardial fluid, lung disease, lead positioning)17,18.

There are limited data regarding ECG sensitivity and specificity for detection of LVH in patients with advanced age19,20. This age group will grow in the next years—current estimates are that by 2030 there will be more than 73 million Americans over 65 years21 and 20.4 million Brazilians over 70 years22—and so will the prevalence of age-related diseases. Recently, a new criterion for LVH detection was proposed23—the Peguero Lo-Presti criterion: the sum of the S wave in lead V4 with the deepest S wave in the 12-lead ECG (SD + SV4) with a cutoff of 2.3 mV for female subjects and 2.8 mV for male subjects being considered positive for LVH. The criterion had better AUC than other ECG criteria (Sokolow-Lyon, Cornell voltage, RAvL, RL1). We aim to evaluate the diagnostic performance and clinical applicability of the PLP criterion for LVH detection in older adults, compared to traditional ECG criteria.

Methods

Population

We retrospectively collected data from patients ≥ 70 years old (as of March/31/2018) assisted at our institution—a tertiary care teaching hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil. From January/2017 to March/2018, all outpatients and inpatients in non-critical units who underwent at least one 12-lead ECG test were evaluated, as outlined in the study flowchart (Fig. 1). All patients with Left Bundle Branch Block (LBBB), Right Bundle Branch Block (RBBB), Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter, Atrial Tachycardia, Supraventricular Tachycardia, Advanced AV Block or Ventricular paced rhythm were excluded from the analysis (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. ECG electrocardiography; ICU intensive care unit; LBBB left bundle branch block; RBBB right bundle branch block.

ECG analysis

Standard 12-lead ECGs were acquired at 10 mm/mV calibration and speed of 25 mm/s and all tracings were independently reviewed by two experienced cardiologists from the ECG Unit (NS and MF), blinded to echocardiogram and clinical analysis. In case of discordance, the ECG tracing was reviewed by a third cardiologist (CAMT). Four LVH criteria were calculated from the ECG tracings: Peguero-Lo Presti, Cornel, Sokolow-Lyon, and Romhilt-Estes. The value for the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion was obtained with the sum of the deepest S wave in the tracing plus the S wave amplitude in V4 (SD + SV4), with a cutoff for LVH as described previously23: ≥ 2.3 mV for female and ≥ 2.8 for male. The Cornell voltage used a sex-specific voltage criterion as a sum of the R wave in avL plus the S or QS wave in V3 (RavL + SV3) with a cutoff of > 2.0 mV for female and > 2.8 for male24. The Sokolow-Lyon was calculated by adding the S wave amplitude in V1 plus the R wave amplitude in V5 or V6, with a cutoff of ≥ 3.5 mV considered positive for LVH25. The Romhilt and Estes scoring system was obtained through a sum of 6 characteristics obtained from the ECG: voltage criteria, ST-T abnormalities, left-atrial involvement, QRS axis and duration, intrinsicoid deflection; the point system is summarized in the Supplementary Table S1, available in the supplementary information—for patients with ≥ 4 points the LVH is termed probable and ≥ 5, definite26.

Echocardiography analysis

All echocardiograms were performed at our institution, in accordance with national27 and international guidelines28. Left Ventricular Mass was calculated using the Devereux formula: left ventricular mass (g) = 0,80 × 1,04 [(septal thickness + internal diameter + posterior wall thickness)3 − (internal diameter)3] + 0.6 g29, and indexed by the Body Surface Area (BSA), calculated by the Dubois Formula (BSA = 0.007184 × height (m)0.725 × weight (kg)0.425, with LVH defined as > 95 g/m2 in females and > 115 g/m2 male subjects. Echocardiograms were used as the gold-standard method to diagnose LVH.

Clinical data

Epidemiological data from all patients were retrieved from the electronic medical record: anthropometric data (height, weight, body mass index), age in years (at the day of echocardiogram exam), comorbidities as diagnosed by the attending physician (hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, prior myocardial infarction, coronary artery by-pass surgery, prior percutaneous coronary intervention, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), medications prescribed (beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin II receptors blockers (ARB), hydralazine/nitrate). Vital signs were obtained through chart review (blood pressure and heart rate).

Statistical analysis

Baseline clinical and echocardiographic variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables, according to the diagnosis of LVH assessed by the echocardiogram. Continuous variables were compared between groups by means of Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test and categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test.

Sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predicted values for each ECG criteria were calculated, based on the detection of LVH on the echocardiogram. For comparison between the ECG criteria, we tested for lack of agreement between the tests using the McNemar’s test separately for those with echocardiogram-detected LVH and those without30. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were created by plotting the sensitivity over 1-specificity of each test and the areas under the curves (AUC) were estimated and compared31, using the voltage sums for the Peguero-Lo Presti, Sokolow-Lyon and Cornell voltage criteria and the sum of points for the Romhilt and Estes scoring system.

Further performance comparison was done with the F1 score, defined as the harmonic mean of precision (positive predictive value) and recall (sensitivity), ranging from 0 to 100%, with higher scores indicating better model. The F1 score was calculated as F1 = 2*(sensitivity−1 + positive predictive value−1)−1, where positive predictive value is defined as the number of tests correctly identified as positive divided by the total of positives tests32. An additional exploratory analysis was carried out to evaluate the diagnostic performance of combined ECG criteria in a stepwise fashion (combining two, three or all ECG criteria).

We used the decision curve analysis framework to incorporate clinical decision making33 in our analysis. Following this approach, the net-benefit (NB) for each ECG criteria was calculated by subtracting the proportion of false positives from the true positives, weighted by the relative harm of a false positive and false negative result. Scores were then compared against common strategies of treating all and none of the patients, by subtracting the estimated net-benefit of treating-all strategy from the respective criteria. The resulting net benefit was further used to calculate the number of avoidable interventions (for every 100 patients). Briefly, this method considers how much the physician is willing to treat false positives to avoid not treating a false negative patient. A detailed explanation can be found elsewhere33. In our study, the evaluated intervention is ordering an echocardiogram to screen or confirm the diagnosis of LVH. In high resource settings, where echocardiogram is widely available, physicians might tolerate more false positives to avoid missing a true positive (low threshold), whereas in under-resourced settings, the same strategy can lead to waste of scarce resources. Threshold probabilities were selected a priori and chosen to mimic both high (0.1–0.3) and under-resourced (0.3–0.6) theoretical clinical scenarios where elective echocardiogram availability and waiting times are supposed to vary.

We based our manuscript in the 2015 Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD)34,35 (Supplementary Table S2, available in the Supplementary Information). A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses and no adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14.2, Stata Corp LLC36 and R software, version 3.6.2.37.

Ethics and consent

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital das Clínicas, Medicine School, University of São Paulo, Brazil (protocol number 3.210.301, project number 08797119.1.0000.0068 on 03/20/2019) and the need for individual signed informed consent was waived. We declare that all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Demographic data

A total of 592 patients were included, 351 without LVH and 241 with LVH, as defined by the echocardiogram. Table 1 summarizes the demographic data of the study population.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| Demographic data | Non-LVH patients (n = 351) | LVH patients (n = 241) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 77.2 ± 5.9 | 77.9 ± 5.8 | 0.075 |

| Female | 162(46.2%) | 139(57.7%) | 0.006 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 ± 4.32 | 26.3 ± 3.9 | 0.837 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 130.5 ± 20.4 | 135.8 ± 23.4 | 0.004 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.0 ± 10.6 | 75.9 ± 11.9 | 0.880 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 68.0 ± 14.3 | 69.2 ± 19.1 | 0.361 |

| Hypertension | 288 (82.1%) | 204 (84.7%) | 0.408 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 118 (33.6%) | 95 (39.4%) | 0.149 |

| Dyslipidemia | 196 (55.8%) | 122 (50.6%) | 0.211 |

| Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | 62 (17.7%) | 35 (14.5%) | 0.310 |

| Coronary artery disease | 184 (52.4%) | 124 (51.5%) | 0.817 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 105 (29.9%) | 76 (31.5%) | 0.674 |

| Previous CABG | 58 (16.5%) | 45 (18.7%) | 0.498 |

| Previous PCI | 105 (29.9%) | 57 (23.7%) | 0.093 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 18 (5.1%) | 28 (11.6%) | 0.004 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 30 (8.6%) | 32 (13.3%) | 0.065 |

| Medication use | |||

| ACEi | 85 (24.2%) | 82 (34.0%) | 0.009 |

| ARBs | 138 (39.3%) | 87 (36.1%) | 0.428 |

| CCBs | 86 (24.5%) | 69 (28.6%) | 0.262 |

| Beta blocker | 197 (56.1%) | 151 (62.7%) | 0.113 |

| Hydralazine/nitrate | 25 (7.1%) | 36 (14.9%) | 0.002 |

| Diuretic | 140 (39.9%) | 143 (59.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Days between echocardiogram and ECG* | 7 (0–39) | 14 (0–42) | 0.269 |

Demographic data of the cohort, according to the left ventricular hypertrophy status evaluated by echocardiography. Values are mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

ACEi angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs angiotensin receptor blockers; BMI body mass index; CABG coronary artery bypass graft; CCBs calcium channel blockers; DBP diastolic blood pressure; PCI percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP systolic blood pressure.

*Median and interquartile rate.

Echocardiographic parameters

Patients with LVH had distinctive echocardiographic features: lower ejection fraction, higher mass index, increased diameters (left atrium, interventricular septum, posterior wall, left-ventricular end systolic and diastolic) and relative wall thickness (RWT) and higher prevalence of valvular heart disease (moderate or severe aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation and mitral regurgitation, p < 0.001 for all comparisons) (available in the Supplementary information, Table S3).

Interobserver agreement

Voltage-based criteria had a near perfect agreement as assessed by Cohen’s kappa statistic, with all criteria above 0.90 (Cornell Voltage 0.90, Sokolow-Lyon 0.93 and Peguero-Lo Presti 0.95, all p-values < 0.001). For the Romhilt-Estes scoring system, the agreement between the two observers was moderate (Cohen’s kappa 0.48, p < 0.001).

Diagnostic performance of the ECG criteria

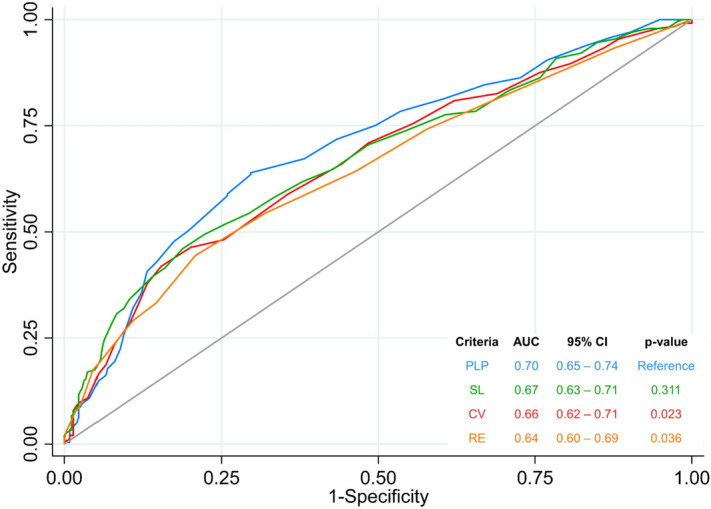

Discriminative power assessed by the area under the curve (AUC)

The Peguero-Lo Presti criterion had a significantly higher AUC than the Cornell Voltage and Romhilt-Estes criteria (respectively, 0.70 (95% CI 0.65–0.74) vs 0.66 (95% CI 0.62–0.71) vs 0.64 (95% CI 0.60–0.69), respectively, p < 0.05) and a similar AUC compared to the Sokolow-Lyon criterion (AUC = 0.67 (95% CI 0.63–0.71), p = 0.311, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

ROC curve and AUC for all ECG evaluated criteria. AUC of the ECG criteria, using the echocardiogram as the reference for LVH. All criteria were compared against the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion. AUC area under the curve; CI Confidence Interval; Ref reference.

Sensitivity

The Peguero-Lo Presti criterion had higher sensitivity compared to the Sokolow-Lyon voltage (51.9% [95% CI 45.4–58.3%] vs. 28.2% [95% CI 22.6–34.4%]; p < 0.0001), Cornell Voltage (35.3% [95% CI 29.2–41.7%]; p < 0.0001), Romhilt-Estes pointing system with the 5 points cutoff (RE5; 44.4% [95% CI 38–50.9%], p = 0.042) and similar sensitivity compare to the Romhilt-Estes pointing system with the 4 points cutoff (RE4; 54.4% [95% CI 47.8–60.8%], p = 0.497); all analyses using the McNemar’s test for patients with LVH in the echocardiogram.

Specificity

The specificity of the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion (82.1% [95% CI 77.6–85.9%]) was inferior to the Cornell Voltage and Sokolow-Lyon criteria (89.7% [95% CI 86.1–92.7%] and 92.6% [95% CI 89.3–95.1%], respectively, with p < 0.0001 for both comparisons using the McNemar’s test for patients without LVH in the echocardiogram. The Peguero-Lo Presti criterion had higher specificity than the RE4 (68.1% [95% CI 62.9–72.9%], p < 0.001) and similar specificity compared to the RE5 (79.2% [95% CI 74.6–83.3%], p = 0.275).

Diagnostic performance

The Peguero-Lo Presti had the highest F1 score (58.3%), followed by the Romhilt-Estes 4 points cutoff (54.1%), the Romhilt-Estes 5 points cutoff (50.8%), the Cornell Voltage (47.0%) and finally the Sokolow-Lyon voltage (40.6%). Diagnostic performance of the ECG criteria is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Diagnostic performance of the ECG criteria.

| LVH criteria | Reference: Echocardiogram | Reference: Peguero-Lo Presti | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | F1 Score (%) | McNemar test LVHa (comparing sensitivity) | McNemar test no LVHb (comparing specificity) | |

| Sokolow-Lyon voltage | 28.2 (22.6–34.4) | 92.6 (89.3–95.1) | 72.3 | 65.3 | 40.6 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Cornell voltage | 35.3 (29.2–41.7) | 89.7 (86.1–92.7) | 70.2 | 66.9 | 47.0 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Peguero-Lo Presti | 51.9 (45.4–58.3) | 82.1 (77.6–85.9) | 66.5 | 71.3 | 58.3 | – | – |

| Romhilt Estes 4 points | 54.4 (47.8–60.8) | 68.1 (62.9–72.9) | 53.9 | 68.5 | 54.1 | 0.497 | < 0.001 |

| Romhilt Estes 5 points | 44.4 (38.0–50.9) | 79.2 (74.6–83.3) | 59.4 | 67.5 | 50.8 | 0.042 | 0.275 |

Comparison of the performance of the ECG criteria aMcNemar test comparing other ECG criteria versus Peguero-Lo Presti in patient with LVH in echocardiogram; bMcNemar test comparing other ECG criteria versus Peguero-Lo Presti in patient without LVH in the echocardiogram; a and b = p < 0.05 indicates lack of agreement.

CI confidence interval; NPV negative predictive value; PPV positive predictive value.

Combination of ECG criteria

The Peguero-Lo Presti criterion also had the highest sensitivity in combination of two (with RE4) or three criteria (with RE4 and Cornell Voltage or RE4 and Sokolow-Lyon) and overall F1 Score (combined with the Sokolow-Lyon and Cornell voltage criteria). Diagnostic performance of combined ECG criteria is summarized in the Supplementary Table S4.

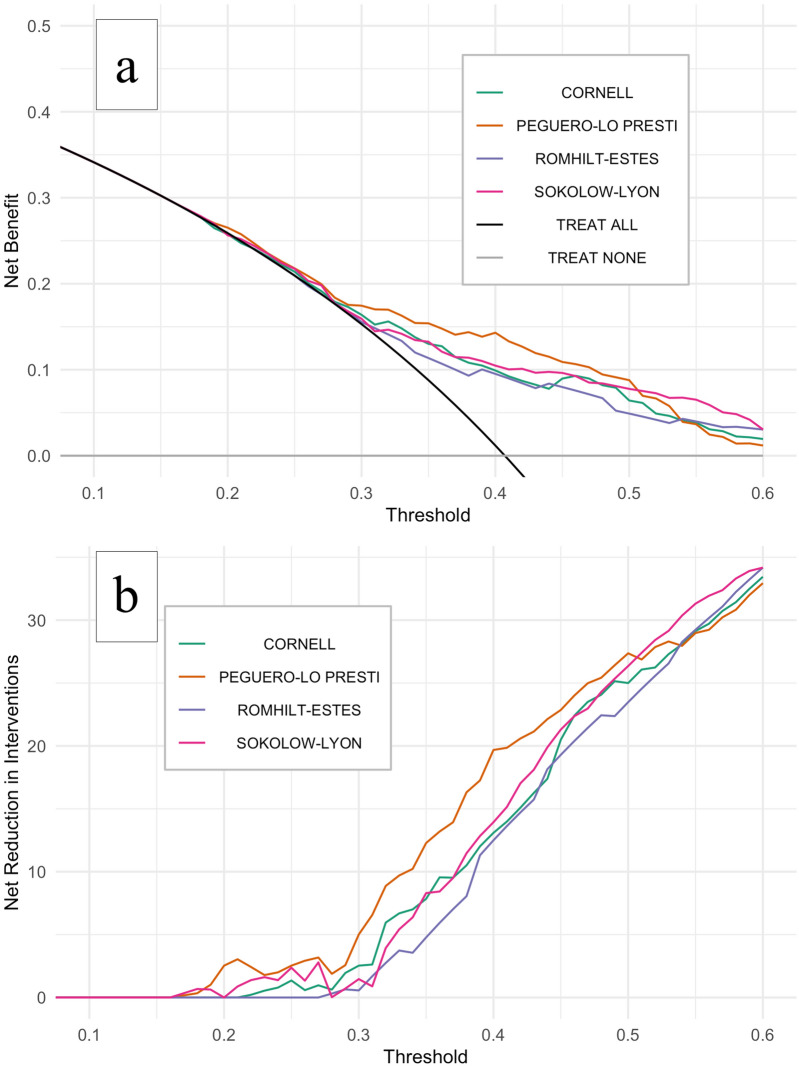

Decision curve analysis

The Peguero-Lo Presti criterion had the best net benefit for most 20–60% threshold range as shown in Fig. 3a,b. For thresholds in-between 10 and 20% (low probability threshold scores, applicable to high resource settings, i.e., when physicians might tolerate more false positives ECGs to avoid missing LVH on echocardiogram), we found no/little clinical usefulness for all ECG criteria compared to ordering echocardiograms for all patients. For a probability threshold of 40%(moderate to high probability threshold scores, applicable to under-resourced settings, i.e., when physicians might tolerate fewer false positives to curb ordering of unnecessary echocardiograms) the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion would avoid nearly 20 exams (out of 100 screened patients) when compared to the hypothetical strategy of ordering echocardiogram for all patients. Also, when compared to all other ECG criteria for most 20–60% threshold range, the implementation of the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion would decrease the number of echocardiograms needed to diagnose one patient with echocardiographic LVH (true positive results) without missing additional patients with echocardiographic LVH (false negative results). For illustrative purposes, the impact of screening 100 patients at-risk of LVH with each ECG criterion based on our dataset, using a 40% probability threshold, is pictured in Supplementary Fig. S2 and a direct comparison among all ECG criteria according to varying probability thresholds is summarized in the Supplementary Table S5.

Figure 3.

Decision curve analysis for the ECG criteria. Decision curve analysis showing the effect of ECG criteria on the detection of left ventricular hypertrophy as assessed by echocardiogram. Net benefit is plotted against the risk threshold at which the clinician would opt for ordering echocardiogram, compared to strategies of performing echocardiogram to all patients (black line) or none (grey line) (a). (b) Shows the net reduction in echocardiograms ordered by using different ECG criteria (as shown in the number of unnecessary echocardiograms avoided per 100 patients). Probability threshold range (0.1–0.6) reflect different relative values for harm (performing an echocardiogram in patients without LVH, i.e., false positives) and benefit (identifying a true positive) and were selected a priori to mimic both high (0.1–0.3) and under-resourced (0.3–0.6) theoretical clinical scenarios where elective echocardiogram availability and waiting times are supposed to vary.

Discussion

The development of accurate ECG criteria for LVH is an unmet need in Cardiology, especially in the elderly, where very few data are available. In this study, we demonstrated that the PLP had superior performance when compared to the other ECG criteria using the AUC, the F1 score and the decision curve analysis. To the best of our knowledge, we report three new comparisons for the first time: the first between the recently proposed Peguero-Lo Presti criterion and traditional ECG criteria in the elderly, an age group systematic underrepresented in other cohorts. Second, we compared the Peguero-Lo Presti versus the Romhilt-Estes scoring system (that unlike the other criteria, considers more than only the QRS complex voltage for LVH diagnosis). Third, we used the decision curve analysis to help clinicians use a selective strategy to perform echocardiogram in patients at risk of LVH.

After the original publication of the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion several other groups compared the sensitivity of the novel electrocardiographic criterion with other ECG criteria with conflicting results32,38–45. The PLP criterion also predicted LVH in another cohort of patients with aortic stenosis46 and mortality in a clustered probability sample of the general population5. Also, in a cohort of apparently healthy individuals47, the specificity of the PLP criterion seemed to be higher in older rather than young individuals. We believe our results add relevant findings: the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion had the highest discriminative performance compared to all other criteria, as assessed by the AUC and the F1 score. We also have shown that, despite previous concerns about its generalizability in certain populations not properly represented in the original publication39, the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion can be used in elderly patients with the proposed cut-offs, having an improved sensitivity compared to other voltage criteria and similar sensitivity to the more complex and laborious Rohmilt-Estes scoring system.

Despite the higher sensitivity of the Peguero Lo–Presti criterion, it would not be suitable as a screening test in our population, because near 1 out of 2 patients with LVH would be missed—even in a population from a tertiary center with high prevalence of disease, where sensitivity is probably overestimated due to the spectrum effect48. An alternative approach that deserves further exploration to overcome this ECG limitation is to combine different criteria49,50, aiming to increase sensitivity and helping surpass the historical inability of the ECG to rule out LVH51. Indeed, findings from our exploratory analysis suggests that combination of ECG criteria using the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion increased sensitivity and performance (F1 score) of the ECG.

As the optimal strategy to screen for LVH in patients at risk is still to be determined7, the decision curve analysis suggested that the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion might have a role in guiding treatment decisions. The Peguero-Lo Presti provided the best net benefit for most tested thresholds and, compared to other ECG criteria, could optimize the use of echocardiography—a need in low-resource areas, where the waiting time for an elective scheduled echocardiogram can last up to 540 days52. As a low-cost, ubiquitous and easily accessible test, the ECG is theoretically the perfect tool for both diagnosis and follow-up of LVH worldwide.

Study limitations

This was a retrospective single-center study and several limitations bear acknowledgement. First, the gold standard for LVH diagnosis was the two-dimensional echocardiogram that is known to be an operator-dependent test and inferior to MRI53. Second, we could not adjust the Sokolow-Lyon voltage product according to body mass index as proposed by Rider and colleagues54. Third, since mortality and other long-term cardiovascular endpoints were not available, we could not test the hypothesis that ECG-based LVH assessed by the Peguero-Lo Presti (named electrical LVH) has prognostic implications besides anatomic-based LVH—as both ECG-LVH and echocardiographic LVH may provide prognostic information55. Fourth, because we excluded patients with bundle branch blocks, pacemaker and atrial fibrillation, our findings cannot be extrapolated to these groups. Fifth, even though Brazil is a highly ethnically diverse country, ethnic background was not routinely accessed and extrapolations of our findings to certain populations must be done with caution. Finally, our population is representative of a tertiary center with a high burden of cardiovascular disease, which may limit generalizability to the general population. Despite these limitations, we consider that our method is aligned with current clinical practice, where echocardiogram is the most frequently method to assess for LVH and the ECG criteria is rarely adjusted for body habitus. Also, our methodology was very similar to the original publication of the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion23.

Conclusion

Compared to other ECG criteria, the Peguero-Lo Presti criterion had the best diagnostic performance in elderly patients and can potentially be used to guide a selective approach to echocardiogram ordering in low-resource settings. The sensitivity of this criterion, however, remains low and far from what would be expected as a screening tool. Further investigation—possibly by combining different ECG criteria—is needed to fill this long-standing knowledge gap in Cardiology, especially in patients with advanced age, systematically excluded and underrepresented in clinical research.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Julia Fukushima for the help with biostatistical analysis and Ms. Elisângela Alcântara for general assistance.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CI

Confidence interval

- CV

Cornell voltage criterion

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- LVH

Left ventricular hypertrophy

- PLP

Peguero-Lo Presti criterion

- RE

Romhilt-Estes criterion

- SL

Sokolow-Lyon voltage criterion

Author contributions

C.A.M.T., M.F. and N.S. planned the study and primarily wrote the manuscript. L.C.G. did the primary statistical analysis, and with M.E.F. contributed to methodology, writing and editing. E.M.P. and F.L.N. did data acquisition and contributed to writing and editing. C.A.P., L.A.H. and W.J.F. helped conceive the original idea of the study and supervised the findings of the work to the final written manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

Michael E. Farkouh: research grants from Amgen, Novartis and Novo Nordisk; the other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-91083-9.

References

- 1.Sundstrom J, et al. Echocardiographic and electrocardiographic diagnoses of left ventricular hypertrophy predict mortality independently of each other in a population of elderly men. Circulation. 2001;103:2346–2351. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.19.2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haider AW, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are associated with increased risk for sudden death. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998;32:1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narayanan K, et al. Electrocardiographic versus echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and sudden cardiac arrest in the community. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:1040–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bang CN, et al. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy predicts cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients: The ALLHAT study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2017;30:914–922. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afify HMA, et al. Peguero electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy criteria and risk of mortality. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018;5:75. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antikainen RL, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy is a predictor of cardiovascular events in elderly hypertensive patients: Hypertension in the very elderly trial. J. Hypertens. 2016;34:2280–2286. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whelton PK, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mancia G, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) J. Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–1357. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000431740.32696.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kannel WB, Gordon T, Castelli WP, Margolis JR. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of coronary heart disease. The Framingham study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1970;72:813–822. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-72-6-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuspidi C, et al. Do combined electrocardiographic and echocardiographic markers of left ventricular hypertrophy improve cardiovascular risk estimation? J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2016;18:846–854. doi: 10.1111/jch.12834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bang CN, Devereux RB, Okin PM. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy or strain is associated with lower incidence of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients independent of blood pressure reduction - A LIFE review. J. Electrocardiol. 2014;47:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rautaharju PM, et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part IV: the ST segment, T and U waves, and the QT interval: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;53:982–991. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pewsner D, et al. Accuracy of electrocardiography in diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in arterial hypertension: Systematic review. BMJ. 2007;335:711. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39276.636354.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krittayaphong R, et al. Accuracy of ECG criteria for the diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy: a comparison with magnetic resonance imaging. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96(Suppl 2):S124–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman A, Prokupetz A, Koren-Morag N, Grossman E, Shamiss A. Comparison of usefulness of Sokolow and Cornell criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy in subjects aged <20 years versus >30 years. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012;110:440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanna EB, Glancy DL, Oral E. Sensitivity and specificity of frequently used electrocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with anterior wall myocardial infarction. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2010;23:15–18. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2010.11928573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willems JL, Poblete PF, Pipberger HV. Day-to-day variation of the normal orthogonal electrocardiogram and vectorcardiogram. Circulation. 1972;45:1057–1064. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.45.5.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horton JD, Sherber HS, Lakatta EG. Distance correction for precordial electrocardiographic voltage in estimating left ventricular mass: An echocardiographic study. Circulation. 1977;55:509–512. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.55.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laszlo R, et al. Accuracy of ECG indices for diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in people >65 years: Results from the ActiFE study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2017;29:875–884. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0667-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casiglia E, et al. Left-ventricular hypertrophy in the elderly: Unreliability of ECG criteria in 477 subjects aged 65 years or more. The CArdiovascular STudy in the ELderly (CASTEL) Cardiology. 1996;87:429–435. doi: 10.1159/000177132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grayson, K. & Vincent, V. A. V. Current Population Reports. U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. https://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf. Accessed 26 Dez 2020.

- 22.Insituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). 2010. https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv49230.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

- 23.Peguero JG, et al. Electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;69:1694–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casale PN, et al. Electrocardiographic detection of left ventricular hypertrophy: Development and prospective validation of improved criteria. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1985;6:572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(85)80115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sokolow M, Lyon TP. The ventricular complex in left ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads 1949. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2001;6:343–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2001.tb00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romhilt DW, Estes EH., Jr A point-score system for the ECG diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am. Heart J. 1968;75:752–758. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(68)90035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barberato SH, et al. Position statement on indications of echocardiography in adults—2019. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2019;113:135–181. doi: 10.5935/abc.20190129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marwick TH, et al. Recommendations on the use of echocardiography in adult hypertension: A report from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015;28:727–754. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devereux RB, Reichek N. Echocardiographic determination of left ventricular mass in man. Anatomic validation of the method. Circulation. 1977;55:613–618. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.55.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim S, Lee W. Does McNemar's test compare the sensitivities and specificities of two diagnostic tests? Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2017;26:142–154. doi: 10.1177/0962280214541852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. doi: 10.2307/2531595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sparapani R, et al. Detection of left ventricular hypertrophy using Bayesian additive regression trees: The MESA. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e009959. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med. Decis. Mak. 2006;26:565–574. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen JF, et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012799. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bossuyt PM, Cohen JF, Gatsonis CA, Korevaar DA, group, S. STARD 2015 Updated reporting guidelines for all diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015;4(85):2016. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2016.02.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seed P. "DIAGT: Stata Module to Report Summary Statistics for Diagnostic Tests Compared to True Disease Status." Statistical Software Components S423401, Boston College Department of Economics, revised 19 Feb 2010. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s423401.html. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

- 37.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Project, 2017. https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

- 38.Narita M, et al. Novel electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in the Japanese general population. Int. Heart J. 2019;60:679–687. doi: 10.1536/ihj.18-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun GZ, Wang HY, Ye N, Sun YX. Assessment of novel Peguero-Lo Presti electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy criteria in a large Asian population: Newer may not be better. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018;34:1153–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ricciardi D, et al. Current diagnostic ECG criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy: Is it time to change paradigm in the analysis of data? J. Cardiovasc. Med. (Hagerstown) 2020;21:128–133. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snelder SM, et al. Optimized electrocardiographic criteria for the detection of left ventricular hypertrophy in obesity patients. Clin. Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/clc.23333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shao Q, et al. Newly proposed electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in a Chinese population. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2019;24:e12602. doi: 10.1111/anec.12602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guerreiro C, et al. Peguero-Lo Presti criteria for diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy: A cardiac magnetic resonance validation study. J. Cardiovasc. Med. (Hagerstown) 2020;21:437–443. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia Y, et al. Diagnostic capability and influence factors for a new electrocardiogram criterion in the diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in a Chinese population. Cardiology. 2020;145:294–302. doi: 10.1159/000505421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang X, et al. Electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of abnormal hypertensive cardiac phenotypes. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2019;21:372–378. doi: 10.1111/jch.13486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramchand J, et al. The Peguero-Lo Presti electrocardiographic criteria predict all-cause mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70:1831–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macfarlane PW, Clark EN, Cleland JGF. New criteria for LVH should be evaluated against age. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70:2206–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Usher-Smith JA, Sharp SJ, Griffin SJ. The spectrum effect in tests for risk prediction, screening, and diagnosis. BMJ. 2016;353:i3139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okin PM, Hille DA, Kjeldsen SE, Devereux RB. Combining ECG criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy improves risk prediction in patients with hypertension. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porthan K, et al. ECG left ventricular hypertrophy as a risk predictor of sudden cardiac death. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019;276:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferdinand KC, Maraboto C. Is electrocardiography-left ventricular hypertrophy an obsolete marker for determining heart failure risk with hypertension? J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012457. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nascimento BR, et al. Integration of echocardiographic screening by non-physicians with remote reading in primary care. Heart. 2019;105:283–290. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rautaharju PM, Soliman EZ. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events: a critical appraisal. J. Electrocardiol. 2014;47:649–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rider OJ, et al. Improvements in ECG accuracy for diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in obesity. Heart. 2016;102:1566–1572. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aro AL, Chugh SS. Clinical diagnosis of electrical versus anatomic left ventricular hypertrophy: Prognostic and therapeutic implications. Circ. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e003629. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.