Abstract

Background:

Few studies have assessed the financial impact of cancer diagnosis on patients and caregivers in diverse clinical settings. S1417CD, led by the SWOG Cancer Research Network, is the first prospective longitudinal cohort study assessing financial outcomes conducted in the NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP). We report our experience navigating design and implementation barriers.

Methods:

Patients age ≥ 18 within 120 days of metastatic colorectal cancer diagnosis were considered eligible and invited to identify a caregiver to participate in an optional substudy. Measures include 1) patient and caregiver surveys assessing financial status, caregiver burden, and quality of life and 2) patient credit reports obtained from the credit agency TransUnion through a linkage requiring social security numbers and secure data transfer processes. The primary endpoint is incidence of treatment-related financial hardship, defined as one or more of the following: debt accrual, selling or refinancing home, ≥20% income decline, or borrowing money. Accrual goal was n=374 patients in 3 years.

Results:

S1417CD activated on Apr 1, 2016 and closed on Feb 1, 2019 after reaching its accrual goal sooner than anticipated. A total of 380 patients (median age 59.7 years) and 155 caregivers enrolled across 548 clinical sites. Credit data were not obtainable for 76 (20%) patients due to early death, lack of credit, or inability to match records.

Conclusions:

Robust accrual to S1417CD demonstrates patients’ and caregivers’ willingness to improve understanding of financial toxicity despite perceived barriers such as embarrassment and fears that disclosing financial status could influence treatment recommendations.

Keywords: Healthcare Economics and Organizations, Healthcare Disparities, Clinical Oncology

Introduction:

“Financial toxicity” is a term that reflects the spectrum of financial hardships that cancer patients face, including the material, psychological, and behavioral aspects.1,2 A growing body of literature suggests that cancer patients who experience financial hardship are at greater risk for poorer quality of life, worse survival, and more intense care at end of life.3–5 Caregivers share in this experience of financial hardship through depletion of shared household assets, out-of-pocket spending, and loss of work opportunities and income.6–11 These financial experiences may impede caregivers’ ability to perform the demanding roles of outpatient symptom and medication management and may negatively impact quality of life.

The National Cancer Institute (NCI), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and other organizations have recognized financial hardship as a growing survivorship issue in oncology.12–14 Yet major gaps remain in our understanding of the incidence and progression of financial hardship in newly diagnosed cancer patients. This is due, in part, to fact that many patients do not routinely discuss their financial concerns due to shame, being overwhelmed, and fears about receiving inferior treatment if they disclose debt or poor credit.15 Most published studies have utilized cross-sectional surveys administered months to years after cancer diagnosis; recall bias, particularly in relation to complex personal financial information, is a major limitation. Further, studies have focused on either the patient or the caregiver experience, but not both simultaneously in the context of a single prospective study.

Developing policy solutions and interventions to mitigate financial hardship in cancer patients and their caregivers requires a clear understanding of why and when financial hardships develop using both self-reported and objective financial measures. SWOG S1417CD ‘Development of a Prospective Financial Impact Assessment Tool in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (mCRC)’ is a prospective longitudinal cohort study that responds to this need by assessing financial outcomes in patients with mCRC and their caregivers at multiple time points over a 12-month time horizon. This study focuses on mCRC because it is a common malignancy for which multiple expensive drugs have been approved over the past decade. While these treatments have improved median survival to 30 months, the impact on patients’ and caregivers’ financial status is poorly understood.16 S1417CD was conducted through the SWOG Cancer Research Network, one of the largest of the NCI network clinical trials groups, and a member of the NCI’s Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP). The broad reach of the SWOG network, especially to community sites participating through the NCORP, provided a unique opportunity to study patients seen and treated at community practices, including practices that predominantly serve minority and underserved populations. S1417CD represents the first national cooperative group-led study addressing financial hardship in cancer patients. In this paper, we present the unique opportunities and challenges in study design and implementation of this novel study.

Methods:

Study Design

S1417CD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02728804) is a prospective cohort study that longitudinally assesses financial status in newly diagnosed mCRC patients and their informal caregivers (Figure 1). The primary objective of this study is to determine the cumulative incidence of patient self-reported financial hardship at 12 months, defined as one of the following: new debt accumulation, selling or refinancing home, ≥ 20% income decline, or borrowing money of any amount from family/friends. A similar definition of major financial hardship has been used in prior retrospective studies and has been estimated to affect 20–40% of cancer patients.17–19 Our secondary objectives were to 1) assess demographic factors associated with increased risk of financial hardship, 2) explore whether major financial hardship is associated with poorer health-related quality of life over time, 3) profile the magnitude and timing of treatment-related changes in patients’ income, assets, debt, and employment, and to quantify and categorize out-of-pocket expenses (e.g. medical, non-medical) during the 12-month period, 4) to explore the extent to which health insurance factors (e.g. high copayments, deductibles, premiums, loss/change of insurance plan) are associated with major financial hardship and cost-related treatment non-adherence, 5) to determine the feasibility of recruiting informal cancer caregivers to assess caregiver burden and perceptions about treatment costs, and 6) to obtain objective measures of expenses, debt, and credit through linkage with individual patient credit reports at baseline and 12 months.

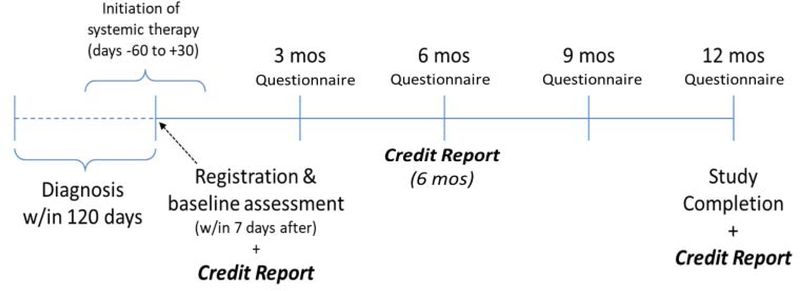

Figure 1: Questionnaire and Credit Report Assessment Schedule*.

*Figure represents study schema after protocol modifications that 1) extended window from diagnosis to registration from 90 to 120 days and 2) allowed for initiation of chemotherapy in the 60 days prior to or 30 days following registration versus requiring registration prior to chemotherapy initiation.

Setting and Patient population

The study setting is the NCI-supported NCORP network that brings cancer care delivery research (CCDR) studies to 46 sites inclusive of over 1000 community oncology practices throughout the country. The NCORP is the ideal environment in which to conduct this study because the diverse population and range of clinical settings makes our findings highly generalizable.

Enrollment was limited to patients with mCRC so that treatments would be similar in intensity and cost. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of several new, expensive CRC drugs over the last decade has increased the cumulative lifetime cost of CRC treatment; the degree to which these costs have been shifted to patients is poorly understood. Finally, as the median survival for metastatic CRC continues to improve, the financial impact of palliative therapy over a longer period may be substantial.

Enrollment was initially limited to patients age ≥ 18 within 90 days of mCRC diagnosis (either de novo or recurrent from previously diagnosed stage I-III CRC) who had not yet started chemotherapy or biologic therapy but were scheduled to receive therapy within 30 days after registration. This specification was intended to minimize recall bias by limiting the treatment-related costs accrued by patients prior to the baseline survey. Patients receiving palliative or hospice care alone were excluded to keep focus on financial hardship related to cancer treatment. Also, patients actively enrolled in other clinical treatment trials were excluded because trials often cover some portion of treatment costs, travel and lodging.

Eligible patients were invited to identify a caregiver to participate concurrently, though caregiver participation was optional. A caregiver is defined as a family member or friend who provides the greatest degree of emotional, physical, logistical, and/or financial support in navigating cancer treatment. Eligible subjects were identified by their oncology providers and consented by the clinical research coordinators in the clinic either before or after scheduled clinic appointments.

Study Questionnaires

The patient financial questionnaires were adapted from (1) a successfully administered questionnaire for a population-based sample of patients with stage III colon cancer; (2) the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS), a large-scale survey of households, employers, and medical providers on the cost and use of health care in the United States; and (3) the University of Michigan’s Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a longitudinal panel survey of older adults.18,20,21 To measure cancer-related quality of life, we included the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ C-30).22 Caregiver questionnaires included demographic questions (age, race, marital status, relationship to caregiver, dependent children, employment status, annual income), questions about financial and social impacts of caregiving (i.e. time spend caregiving, impact on employment, debt, out-of-pocket spending, and income changes), and items measuring caregivers’ stress and anxiety related to cancer treatment expenses, selected from the Family and Cancer Therapy Selection Study (FACTS) survey conducted at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.23 We also included the Caregiver Strain Index, a validated survey of cancer caregiver burden. Additional items were obtained from a survey-based study of caregivers performed by Evercare, in collaboration with the National Alliance for Caregiving, entitled “Family Caregivers: What they Spend, What they Sacrifice.”24,25 Table 1 lists the study surveys, their content, and administration time points. We estimated that each questionnaire would take 45 minutes to complete and could be self-administered at home or clinic or completed by phone interview with the clinical research coordinator. The study team tracked method of survey completion. While SWOG or the investigative team could not centrally provide incentives, individual sites had the option to provide coverage for parking, gas, food, or other monetary incentives for trial participation from their own cancer care delivery research funds.

Table 1:

Study Questionnaires and Administration Schedule

| Questionnaire name | Questionnaire content | Questionnaire time points |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Baseline patient financial, employment, and insurance characteristics – education level, annual income, preexisting debt, total assets (including retirement and savings), baseline employment status.18,20,21 | Registration |

| Financial/Employment Impact | Treatment-related financial or employment changes – accumulation of debt, depletion of assets, inability to pay other bills, changes in income, job loss, borrowing money, selling home.18,20,21 | 3, 6, 9, 12 months |

| Insurance impact | Treatment-related insurance issues and out-of-pocket expenses – insurance coverage denials, high copayments, changes in premiums, treatment non-adherence, all treatment-related out-of-pocket expenses.18,20,21 | 3, 6, 9, 12 months |

| Quality of life | Health-related quality of life – EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ C-30)22 | Registration and 3, 6, 9, 12 months |

| Treatment perceptions | Subjective financial burden assessment – which includes questions assessing stress, anxiety, and guilt related to cancer treatment costs as well as prioritization of treatment costs in the list of disease-related concerns.18,20,21 | Registration and 3, 6, 9, 12 months |

| Caregiver | (Consented caregiver only.) Assessment of financial changes made to accommodate patient’s cancer treatment expenses and subjective caregiver burden assessment (modified Caregiver Strain Index)24,25,33 | Registration, 6, 12 months |

Credit report linkage

A novel aspect of this study was linking patient credit reports at baseline and 12 months with clinical and financial questionnaire data. Credit reports provide an objective measure of financial status that are sensitive to changes over a short time and may correlate with psychosocial distress in patients with cancer and other health conditions.26,27 Lenders, including credit card providers, typically update credit agencies monthly; however, it can take up to 3 months for resolved debt to be reflected in the credit report and 6 months for credit scores to improve based on resolution of outstanding payments. We collaborated with TransUnion, one of three large national credit reporting agencies that provides data on individuals’ credit scores, estimated income, payments and balances on mortgage and installment debt, balances and credit limits for revolving debt (credit cards and home equity lines of credit), foreclosures, and bankruptcies.28 Approximately 90% of Americans have accessed credit markets and thus have credit histories reported with agencies such as TransUnion.29 Although young individuals (age 18–21) and the very poor may be under-represented, TransUnion has data on a large fraction of low-income individuals. A previous study was able to link nearly 70% of participants (all low income and Medicaid eligible) to TransUnion records.30,31

We developed several procedures to address unique challenges associated with accessing credit report information. First, while credit agencies like TransUnion provide data routinely to creditors or lenders (typically with the consumer’s knowledge in the context of a loan or other financial agreement), they have not shared data with academic entities for the purposes of research. Moreover, these agencies do not typically allow outside entities to publish findings related to the credit information or store data for future use. We therefore had to execute both legal and data use agreements between SWOG and TransUnion before activating S1417CD. Second, social security numbers (SSNs), full name, and address were necessary to enable the direct linkage to credit report data yet not routinely collected in many NCI network group studies due to concerns that asking patients for this information could depress trial enrollment (Table 2). The study team preemptively explained the rationale for collecting this information in the protocol.

Table 2:

Additional Data Requirements for Credit Linkage

| Required/Collected Routinely by SWOG | Required specifically for credit linkage | |

|---|---|---|

| Name | No (Initials only, Name optional) | Yes |

| SSN | No (Requested but optional) | Yes |

| Full Street Address | No | Yes |

| Zip Code | Yes | Yes |

| Birth Date | Yes | Yes |

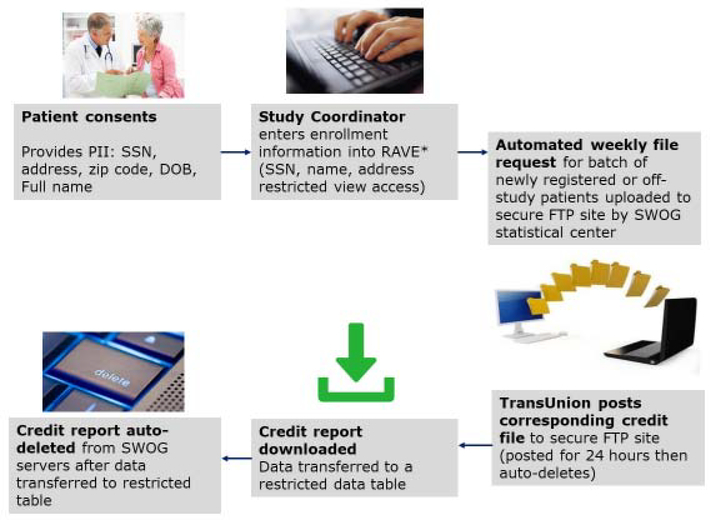

Finally, the study team developed a process to securely transfer credit reports from TransUnion to the SWOG Statistics and Data Management Center (SDMC). A secure file transfer protocol (FTP) site was created; patient identifiers were uploaded to the FTP site by the SWOG team and the corresponding credit reports were then posted to the site by TransUnion, after which the credit data were downloaded and stored in a restricted table accessible only by study statisticians and database administrators. Files were then automatically deleted from the FTP site after 24 hours. To minimize data coordinator effort and provide an extra layer of security around patient identifiers and credit report data, requests for credit reports were batched weekly and automatically submitted via the secure FTP site. Figure 2 summarizes the key credit linkage steps.

Figure 2: Credit Linkage Procedures.

* RAVE (Medidata RAVE) refers to the Electronic Data Capture system used for S1417CD

Statistical considerations

The primary endpoint is time until first evidence of major self-reported financial hardship given serial measures of financial status every 3 months for one year. Because 1-year survival for persons with mCRC is approximately 60%, death represents a substantial competing risk for financial hardship.32 Based on preliminary data, we anticipated that 40% of patients would experience major financial hardship at some point in the first year after diagnosis.18 Accounting for the competing risk of death, 320 evaluable patients were required to allow estimation of the confidence interval to within ± 8% (based on the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval using an exact binomial in patients with complete follow-up). Given non-restrictive eligibility criteria, we anticipated a low rate of ineligibility of 5%. In addition, 10% of patients were anticipated not to complete their baseline forms and would not be evaluable. Thus in total 374 total patients (320/(1-.05)/(1-.10) were required to obtain 320 eligible, evaluable patients over 3 years of enrollment. To adjust for factors that may also influence likelihood of and time to development of self-reported financial hardship (e.g. age, race, disease status (de novo metastatic disease versus recurrent), insurance type), we will conduct a multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine the association between baseline characteristics and self-reported financial hardship.

Results:

Study approval and activation

The study protocol was approved by the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Prevention in October 2015 and was activated in April 2016. NCORP components and subcomponents submitted the protocol to their local institutional IRB.

In response to anticipated queries from study sites and IRBs, the study team assembled a frequently asked questions (FAQ) document addressing data security concerns and the need to collect SSN and other identifiers. In addition, TransUnion was able to provide a letter confirming that the credit linkage would not result in a hard credit inquiry and thus would not affect the consumer’s credit score or any type of credit decisioning process used by a credit lender. Finally, the study team provided study sites and IRBs a complete list of all 248 credit attributes to be provided by TransUnion on each study participant.

Study Enrollment and Protocol Modifications

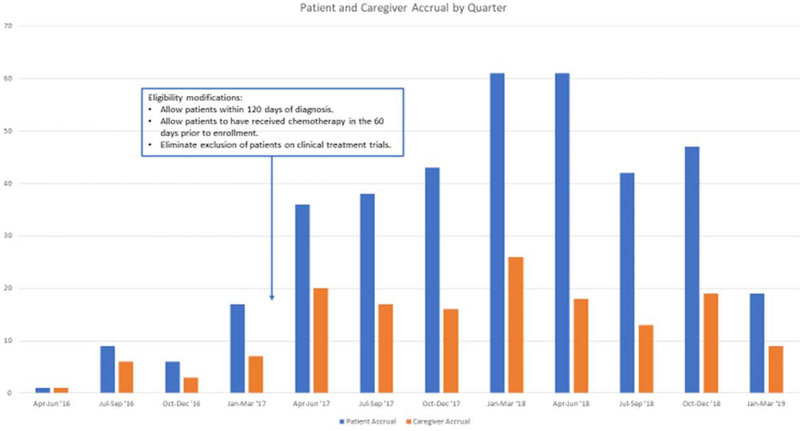

Initial accrual was slow, with only 23 patients and 17 caregivers enrolled in the first year following study activation (Figure 3). Based on feedback from clinical research coordinators at the NCORP sites, the study team identified two key barriers to enrollment. First, the investigators and coordinators voiced discomfort in presenting this study to patients due to uncertainty about its benefit and concerns that patients would be reluctant to participate. To address these concerns, the study team held roundtables at the SWOG group meetings to share enrollment strategies with site investigators. Also, the study team developed a patient brochure outlining basic procedures and the importance of the study for improving the understanding of financial toxicity. In addition, many study coordinators and patient advocates promoted the study through social media and patient support groups.

Figure 3: Patient and Caregiver Accrual to S1417CD.

Second, sites reported difficulty enrolling patients within 90 days of diagnosis who had not yet started chemotherapy due to competing patient appointments and obligations prior to treatment. As such, the eligibility criteria were modified in February 2017 to allow patients within 120 days of diagnosis who had either started chemotherapy in the 60 days prior to registration or were scheduled to start chemotherapy in the coming 30 days. Accrual substantially improved following this modification and we felt that it was most respectful to participants who were already overwhelmed in the initial diagnosis and treatment initiation period. We also eliminated the exclusion for patients concurrently enrolled on other clinical trials and opened the study to all non-SWOG NCORP sites.

Patient and Caregiver Characteristics

S1417CD reached its accrual goal on February 1, 2019. A total of 380 patients were enrolled across 120 NCORP sites more rapidly than anticipated. Demonstrating the reach of the NCORP to minority and underserved patients, 22% of patients were non-white (including 13% black) and the majority had annual income < $50,000 (56%) (Table 3). Nearly all patients (98%) were insured.

Table 3:

Patient and Caregiver Characteristics

| Patient Characteristic | N (%) or Median (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.9 (21.1, 89.3) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 286 (78%) | |

| Black | 49 (13%) | |

| Asian / Pacific Islander | 17 (5%) | |

| Other or unknown | 17 (4%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 232 (61%) | |

| Female | 148 (39%) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Divorced | 65 (18%) | |

| Single (Never Married/Separated/Widowed) | 84 (22%) | |

| Married or Partnered | 219 (60%) | |

| Primary Insurance | ||

| Commercial insurance | 179 (47%) | |

| Medicare | 143 (38%) | |

| Medicaid | 47 (12%) | |

| Veterans/Military Insurance | 1 (0%) | |

| Charity care | 2 (1%) | |

| Uninsured | 7 (2%) | |

| Pre-Diagnosis Employment Status | ||

| Employed (full-time, part-time) | 222 (60%) | |

| Retired | 93 (25%) | |

| Leave of absence | 2 (<1%) | |

| Disability | 25 (7%) | |

| Unemployed | 13 (4%) | |

| Other/Missing | 13 (4%) | |

| Annual Income category | ||

| $0–$15,000 | 57 (15%) | |

| $15,001–$25,000 | 57 (15%) | |

| $25,001–$35,000 | 41 (11%) | |

| $35,001–$50,000 | 57 (15%) | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 55 (15%) | |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 32 (9%) | |

| $100,001–$150,000 | 38 (10%) | |

| $150,001–$200,000 | 13 (4%) | |

| $200,001 or more | 16 (4%) | |

| Not answered by patient | 2 (1%) | |

| Caregiver Characteristic | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 35 (23%) | |

| Female | 117 (77%) | |

| Relationship to patient | ||

| Aunt or Uncle | 1 (1%) | |

| Brother-in-law or sister-in-law | 2 (1%) | |

| Child | 7 (4%) | |

| Friend | 2 (1%) | |

| Parent | 21 (14%) | |

| Parent-in-law | 2 (1%) | |

| Son-in-law or daughter-in-law | 1 (1%) | |

| Sibling | 5 (3%) | |

| Domestic partner or significant other | 17 (11%) | |

| Spouse | 93 (61%) | |

| Other | 1 (1%) | |

Though optional, 40% of patients had a caregiver who concurrently participated (n=152) (Table 3). As expected in this adult population, most caregivers were spouses, partners, or significant others (72%) followed by parents (14%).

Credit report linkage:

Credit reports were successfully obtained on 80% of all patients enrolled. We learned during the study that TransUnion will not release credit reports on persons who have died; thus making reports unavailable for patients who died before the 12-month credit report point. We modified the protocol to access another credit report at 6 months so that a higher proportion will still have evaluable longitudinal credit data.

Discussion:

SWOG S1417CD is the first study led by a cooperative group that addresses financial toxicity in oncology care. After addressing clinics’ concerns about collecting sensitive financial information, accrual completed faster than anticipated. Indeed, patients and caregivers were very willing to provide financial information for the purposes of research. We conclude that overcoming physician and research coordinator discomfort in presenting and discussing this study to patients was a larger barrier than patient unwillingness to participate when asked. This conclusion is supported by the improvement in accrual following educational sessions at SWOG meetings, webinars, and other outreach and training efforts by the study team.

Some limitations with this study should be noted. First, though non-English speaking patients may face unique financial and insurance challenges, we were not able to enroll non-English speakers due to limited budget to translate the surveys into other languages. Second, caregiver enrollment was made optional and thus potentially skews our caregiver sample towards a more participatory and engaged cohort who could potentially have lower caregiver burden and fewer financial concerns. Finally, modifying the protocol to allow patients within 120 days of diagnosis who had already started therapy, though necessary to improve accrual, may influence the accuracy of financial hardship estimates by increasing the observation time during which patients may have accrued treatment costs.

Despite initial concerns about accrual and the ability to collect complex and sensitive financial information from patients and caregivers, S1417CD accrued more quickly than anticipated with strong minority and low income patient representation and successful linkage to credit reports in approximately 80% of cases. S1417CD is a groundbreaking study that signals a commitment to study and prioritize financial toxicity as a major survivorship issue for patients and caregivers. As a result of extensive collaborations and innovative thinking, S1417CD established a precedent for successfully collaborating with credit agencies to link detailed financial records to clinical and other patient data. Our experience suggests that this linkage is feasible for most patients in the community clinical setting. Future studies assessing financial status or investigating interventions to mitigate financial toxicity may feasibly use credit information for patient selection or outcome assessment.

Investigators planning to study financial outcomes using similar methods should take note of the interventions we used to address concerns raised by clinical sites, IRBs, and study participants. A substantial amount of work still needs to be done to address barriers that prevent patients, physicians, and oncology practices from communicating about financial hardship and costs of care. Understanding and addressing these barriers can help align families with appropriate resources, aid in treatment decision-making, and potentially influence policy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This publication supported in part by Conquer Cancer Foundation Career Development Award 2013, SWOG Hope Foundation Charles Coltman Jr Award (2010) and by National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health grant award UG1CA189974. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Tucker-Seeley RD, Thorpe RJ. Material-Psychosocial-Behavioral Aspects of Financial Hardship: A Conceptual Model for Cancer Prevention. Gerontologist. 2019;59(Supplement_1):S88–S93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Minimizing the “financial toxicity” associated with cancer care: advancing the research agenda. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tucker-Seeley RD, Abel GA, Uno H, Prigerson H. Financial hardship and the intensity of medical care received near death. Psychooncology. 2015;24(5):572–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, Provenzale D. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):145–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Moor JS, Dowling EC, Ekwueme DU, et al. Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(1):48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balfe M, Butow P, O’Sullivan E, Gooberman-Hill R, Timmons A, Sharp L. The financial impact of head and neck cancer caregiving: a qualitative study. Psychooncology. 2016;25(12):1441–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azzani M, Roslani AC, Su TT. The perceived cancer-related financial hardship among patients and their families: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(3):889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romito F, Goldzweig G, Cormio C, Hagedoorn M, Andersen BL. Informal caregiving for cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119 Suppl 11:2160–2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4362–4373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Financial Toxicity (Financial Distress) and Cancer Treatment (PDQ(R)): Patient Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. Bethesda (MD)2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(23):3868–3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnipper LE. ASCO Task Force on the Cost of Cancer Care. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(5):218–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML, Buss MK. Understanding patients’ attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(4):e50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz HJ, et al. Effect of First-Line Chemotherapy Combined With Cetuximab or Bevacizumab on Overall Survival in Patients With KRAS Wild-Type Advanced or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2392–2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banegas MP, Guy GP Jr., de Moor JS, et al. For Working-Age Cancer Survivors, Medical Debt And Bankruptcy Create Financial Hardships. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1608–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP Jr., et al. Financial Hardship Associated With Cancer in the United States: Findings From a Population-Based Sample of Adult Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(3):259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health and Retirement Survey. 2019; https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/publications. Accessed Sept 30, 2019.

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditures Panel Survey. 2019; https://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/. Accessed Sept 30, 2019. [PubMed]

- 22.Brown E ABMT and breast cancer: what have we learned? Physician Exec. 1999;25(4):86–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bansal A, Koepl LM, Fedorenko CR, et al. Information Seeking and Satisfaction with Information Sources Among Spouses of Men with Newly Diagnosed Local-Stage Prostate Cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(2):325–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onega LL. Helping those who help others: the Modified Caregiver Strain Index. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(9):62–69; quiz 69–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thornton M, Travis SS. Analysis of the reliability of the modified caregiver strain index. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):S127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dean LT, Nicholas LH. Using Credit Scores to Understand Predictors and Consequences of Disease. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(11):1503–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dean LT, Schmitz KH, Frick KD, et al. Consumer credit as a novel marker for economic burden and health after cancer in a diverse population of breast cancer survivors in the USA. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(3):306–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsey SD, Ganz PA, Shankaran V, Peppercorn J, Emanuel E. Addressing the American health-care cost crisis: role of the oncology community. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(23):1777–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brevoort K, Grimm P, Kambara M. Data Point: Credit Invisibles. http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf. Accessed Sept 30, 2019.

- 30.Baicker K, Finkelstein A. The effects of Medicaid coverage--learning from the Oregon experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):683–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, et al. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year. Q J Econ. 2012;127(3):1057–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1539–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Association of Family Caregiving. Family Caregivers -- What they Spend, What they Sacrifice. 2019; https://www.caregiving.org/data/Evercare_NAC_CaregiverCostStudyFINAL20111907.pdf. Accessed Sept 30, 2019.