Abstract

Background:

Male circumcision reduces the risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in men. We assessed the effect of male circumcision on the incidence and natural history of human papillomavirus (HPV) in a randomized clinical trial in Kisumu, Kenya.

Methods:

Sexually active, 18–24-year-old men provided penile exfoliated cells for HPV DNA testing every six months for two years. HPV DNA was detected via GP5+/6+ PCR in glans/coronal sulcus and in shaft samples. HPV incidence and persistence were assessed by intent-to-treat analyses.

Results:

2,193 men participated (1,096 randomized to circumcision; 1,097 controls). HPV prevalence was 50% at baseline for both groups and dropped to 23.7% at 24 months in the circumcision group, and 41.0% in control group. Incident infection of any HPV type over 24 months was lower among men in the circumcision group than in the control group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52, 0.72). Clearance rate of any HPV infection over 24 months was higher in the circumcision group than in the control group (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.49, 2.34). Lower HPV point-prevalence, lower HPV incidence, and higher HPV clearance in the circumcision group were observed in glans but not in shaft samples.

Conclusion:

Male circumcision reduced the risk of HPV acquisition and reinfection, and increased HPV clearance in the glans.

Impact:

Providing voluntary, safe, and affordable male circumcision should help reduce HPV infections in men, and consequently, HPV-associated disease in their partners.

INTRODUCTION

Infection with oncogenic types of human papillomavirus (HPV) is the major cause of invasive cervical cancer1 and an important cause of oral, penile and anal cancers.2,3 Men play a crucial role in the etiology of cervical, vaginal and vulvar cancers, given transmission of penile HPV infection to female sexual partners.4 Although prophylactic HPV vaccines are available for the prevention of high-risk HPV infections,5,6 current generation HPV vaccines are not widely available in many geographical regions7 and do not provide protection against all high-risk HPV types.8

Male circumcision has been shown in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition.9–11 A second important potential benefit of male circumcision is protection against incident penile HPV infection.12,13 Two RCTs, one in South Africa11 and the other in Uganda14 have shown a protective effect of male circumcision against HPV infection in HIV-negative men. However, data are needed on the effect of male circumcision on clearance of newly acquired (incident) penile HPV infections and the rate of HPV reinfections among men with previously documented HPV infections. Furthermore, information on the effect of male circumcision on anatomical site-specific infections (glans/coronal sulcus compared to shaft) over time within an RCT setting is limited. The male circumcision RCT in Rakai, Uganda, found that male circumcision reduced the 1-year HPV point prevalence in the glans/coronal sulcus and in the shaft, yet results were limited to a subset of approximately 100 participants at one cross-sectional time point.15 In an RCT setting in Kisumu, Kenya, we have previously found evidence that male circumcision was associated with a reduced hazard of acquiring high-viral load (>250 copies/scrape) HPV-16 and HPV-18 infections in the glans, but HPV viral load results for shaft samples were weaker and less precise.16

Based on the same RCT study population in Kenya, we now present additional in-depth results of the effect of male circumcision on penile HPV incidence, clearance, and reinfection over two years of follow-up with penile samples collected separately from the glans/coronal sulcus and the shaft.

METHODS

Study Population, Enrollment, and Follow-up

Uncircumcised men were screened for eligibility between February 2002 and September 2005 to participate in an RCT of male circumcision (clinical trials registration number: NCT00059371).9 The main objective of this RCT was to assess the effect of male circumcision on HIV incidence. Enrollment criteria included being uncircumcised, age 18–24 years, HIV seronegative, sexually active, having blood hemoglobin ≥90 g/L and providing signed informed consent. Participants were recruited from sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics, workplaces, and community organizations and events in Kisumu, Kenya. Participants randomized to the intervention arm underwent male circumcision on the same day as RCT enrollment when the penile samples were collected, or as soon as possible after, mostly within a few days.9 The majority of male circumcisions were completed on the day of randomization (64%), 80% within one day, 85% within two days, 88% within three days, and 95% within six weeks of randomization.9 Analyses presented here are based on an ancillary HPV study nested within this male circumcision RCT. HPV testing was performed on participants consenting to collection of penile exfoliated cells, and who had a minimum of one follow-up visit.

Of 2,784 men enrolled in the main RCT,9 2,299 (83%) men gave consent to provide penile swab samples and had an HPV result at baseline. Of those, 2,193 (95%) had both baseline and follow-up HPV results. Therefore, 2,193 men (uncircumcised at baseline) were included in analyses (1,096 randomized to male circumcision and 1,097 randomized to the control group). At baseline, standardized questionnaires on socio-demographic characteristics and sexual behavior were administered to participants by trained male interviewers. Penile cell, blood and urine samples were collected for testing of HPV and other STIs at baseline, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. Most participants attended their 6-month (91%), 12-month (89%), 18-months (87%), and 24-month (86%) follow-up visits.

The protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards of the Universities of Illinois at Chicago, Manitoba, Nairobi and North Carolina; by RTI International; and by the AmsterdamUMC, location VUmc, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Penile Cell Collection and Processing

Penile exfoliated cells for HPV DNA detection were collected by a trained physician or clinical officer from two anatomical sites: i) glans, coronal sulcus, and inner foreskin tissue (glans specimen); and ii) shaft and external foreskin tissue (shaft specimen), using pre-wetted Type 3 Dacron swabs.17,18 Swabs were placed in 15-mL centrifuge tubes containing 2 mL 0.01 mol/L Tris-HCl, 7.4 pH buffer, and processed on the collection day at the research laboratory by centrifugation at 3,000g for 10 minutes. Cell pellets were resuspended in 0.1 mL of Tris-HCl buffer and frozen at −75°C. Samples were shipped in liquid nitrogen to the Department of Pathology, AmsterdamUMC, location VUmc, for HPV testing.

Type-specific HPV DNA and STI Testing

DNA was isolated from samples using the NucleoSpin 96 Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) and Michrolab Star robotic system (Hamilton, Martinsried, Germany) according to manufacturers’ instructions. Presence of human DNA was evaluated by β-globin polymerase chain reaction (PCR), followed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Overall, β-globin positivity in glans and/or shaft specimens was 63.1% at baseline, 66.7% at 6 months, 77.1% at 12 months, 68.4% at 18 months, and 80.3% at 24 months. The β-globin positivity in glans was 56.7% at baseline, 57.3% at 6 months, 67.0% at 12 months, 59.8% at 18 months, and 71.9% at 24 months. The β-globin positivity in shaft was 35.2% at baseline, 36.8% at 6 months, 46.5% at 12 months, 37.2% at 18 months, and 51.0% at 24 months. Results were similar when analyses were restricted to β-globin-positive samples; thus, analyses utilized HPV DNA data from all penile exfoliated cell specimens, regardless of β-globin positivity, unless otherwise stated.

HPV DNA positivity was assessed by GP5+/6+ PCR, followed by hybridisation of PCR products using an enzyme immunoassay readout with two HPV oligoprobe cocktails that, together, detect 44 HPV types. Subsequent genotyping was performed by reverse line blot hybridization.18–20 HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68 were considered high-risk types. HPV types detected by enzyme immunoassay, but not by reverse line blot genotyping, were designated as HPVX, indicating a type, sub-type or variant not detectable by probes used in enzyme immunoassay.

At baseline, urine samples were tested for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) by PCR (Roche Diagnostics) and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) by culture (BioMed Diagnostics Inc.). If urethral discharge was present, urethral swab specimens were tested for GC and CT by PCR, and GC and TV by culture. If a genital ulcer was present, swabs of the ulcer were tested for Haemophilus ducreyi (HD) by PCR and culture. Serum was tested for herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) antibody (Kalon Biological Ltd); and for HIV antibody using two rapid tests (Determine, Abbott Diagnostic Division, and Unigold, Trinity Biotech), and confirmed by double ELISA (Adaltis Inc.; Trinity Biotech) at the University of Nairobi as previously described.9 Positive serum Rapid Plasma Reagin (Becton, Dickinson and Company) tests for syphilis were confirmed by Treponema pallidum hemagluttination assay (Randox Laboratories Ltd).

Statistical Methods

At any fixed timepoint, men with multiple HPV type infections were considered to have high-risk HPV if one or more high-risk types were detected, and to have low-risk HPV if only low-risk types were detected. Men with untyped HPV infections (HPV-X) were excluded from analyses involving HPV-risk categorizations, unless they had a high-risk HPV type concurrently detected. Unadjusted prevalence risk ratios (PRRs) between the circumcision and control arm were estimated at each study visit, separately by anatomical site, and then overall by combining results from both anatomical sampling sites for the same man. PRRs were calculated for HPV type groupings: any, high-risk, low-risk, single, and multiple infections. HPV analyses utilized data from all penile exfoliated cell specimens regardless of β-globin positivity; sensitivity analyses were conducted restricting analyses to β-globin positive results.

Analyses were conducted to determine the effect of male circumcision on HPV prevalence, incidence, and clearance, where all men were analyzed according to their randomization assignment (intention-to-treat analysis). As-treated analyses were also conducted, which entailed including in the survival models a time-dependent covariate for circumcision status at each follow-up visit to take into account those individuals who did not adhere to their randomization assignment.9

An incident, or acquired, infection was defined as detection of type-specific HPV infection during follow-up that was not present at baseline. Time to incident HPV infection was estimated by assuming that infections were acquired at the midpoint between the last HPV-negative result and first subsequent HPV-positive result. Men were censored at their last visit if they remained negative for that HPV type. Incidence rates for each HPV type or HPV grouping were estimated among participants negative for the given individual HPV type or groupings at baseline. Incidence rate analyses were conducted for the most common HPV types in the glans or shaft and for HPV type groupings, stratified by anatomical site and for the two sites combined. Non-parametric estimates of the cumulative probability of any HPV infection among men who were HPV-negative at baseline were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method, allowing for interval censored infection times.21 Parametric survival models that allow for interval censored data were used to estimate HRs of the effect of male circumcision on time to newly acquired HPV infections.

HPV clearance was defined as a positive type-specific HPV result followed by at least one HPV-negative result for that specific HPV type. HPV clearance was considered to have occurred at the midpoint between dates of the last HPV-positive result and of the first subsequent HPV-negative result. Clearance analyses were conducted among HPV infections present at baseline. HPV infections were used as units of analysis to account for men with multiple-type infections. Non-parametric estimates of the cumulative probability of clearing an HPV infection were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method allowing for interval censored clearance times. The effect of circumcision on HPV clearance was estimated using random effect parametric survival models that allowed for interval censored data and multiple infections per man.

Sub-analyses were conducted to examine type-specific HPV reinfections rates among men who were positive for a given type at baseline, cleared the HPV infection, and then re-acquired the same HPV type; only first repeat infections were counted. Clearance of newly acquired (incident) penile HPV infections not present at baseline were also compared between the circumcision and control groups.

RESULTS

Of 2,193 participating men, the median age was 20 years (interquartile range [IQR],19–22) at baseline. Most participants were of Luo ethnicity (98.5%), unmarried (94.1%), had secondary education (65.2%), and were unemployed (64.0%; Table 1). The percentage of men positive at baseline was 26.9% for HSV2, 4.6% for CT, 2.1% for TV, 2.2% for GC, 0.9% for syphilis, and 0% for HD (Table 1). Median age at first sexual intercourse was 16 years (IQR, 14–17) and median number of lifetime female partners was 4 (IQR, 3–7). Most (87.5%) subjects reported sexual intercourse in the last 6 months; of those, 52.7% used condoms inconsistently and 25.5% never. The two arms had similar demographic characteristics and sexual histories at baseline.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics

| Circumcision group | Control group | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years)╫ | 20 (19–22; 18–28; 1096) | 20 (19–22; 17–24; 1097) | 20 (19–22; 17–28; 2193) |

| Ethnic group | |||

| Luo | 1076 (98.2) | 1085 (98.9) | 2161 (98.5) |

| Other | 20 (1.8) | 12 (1.1) | 32 (1.5) |

| Education level | |||

| Less than secondary | 372 (33.9) | 391 (35.6) | 763 (34.8) |

| Any secondary or above | 724 (66.1) | 706 (64.4) | 1430 (65.2) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed and receiving a salary | 94 (8.6) | 98 (8.9) | 192 (8.8) |

| Self-employed | 303 (27.7) | 294 (26.8) | 597 (27.2) |

| Unemployed | 699 (63.8) | 705 (64.3) | 1404 (64.0) |

| Occupation | |||

| Professional/managerial | 16 (1.5) | 25 (2.3) | 41 (1.9) |

| Skilled worker | 108 (9.8) | 87 (7.9) | 195 (8.9) |

| Semi-skilled worker | 73 (6.7) | 74 (6.7) | 147 (6.7) |

| Unskilled worker | 565 (51.6) | 606 (55.2) | 1171 (53.4) |

| Farm laborer/fisherman | 80 (7.3) | 70 (6.4) | 150 (6.8) |

| Student | 254 (23.2) | 235 (21.4) | 489 (22.3) |

| Marital status | |||

| Not married (no live-in partner) | 1024 (93.8) | 1018 (93.2) | 2042 (93.5) |

| Not married (with live-in partner) | 7 (0.6) | 7 (0.6) | 14 (0.6) |

| Married (not living with wife) | 5 (0.5) | 15 (1.4) | 20 (0.9) |

| Married (living with wife) | 56 (5.1) | 52 (4.8) | 108 (5.0) |

| Physical and laboratory findings | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 15.3 (14.2–16.3; 9.0–21.1; 1086) | 15.3 (14.2–16.3; 8.3–20.1; 1085) | 15.3 (14.2–16.3; 8.3–21.1; 2171) |

| Herpes simplex virus 2 | |||

| Positive | 287 (27.3) | 278 (26.5) | 565 (26.9) |

| Negative | 764 (72.7) | 771 (73.5) | 1535 (73.1) |

| Syphilis | |||

| Positive | 12 (1.1) | 6 (0.6) | 18 (0.9) |

| Negative | 1043 (98.9) | 1049 (99.4) | 2092 (99.2) |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | |||

| Positive | 21 (1.9) | 24 (2.2) | 45 (2.1) |

| Negative | 1064 (98.1) | 1059 (97.8) | 2123 (97.9) |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | |||

| Positive | 30 (2.8) | 17 (1.6) | 47 (2.2) |

| Negative | 1053 (97.2) | 1066 (98.4) | 2119 (97.8) |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |||

| Positive | 57 (5.3) | 42 (3.9) | 99 (4.6) |

| Negative | 1025 (94.7) | 1041 (96.1) | 2066 (95.4) |

| Haemophilus ducreyi | |||

| Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Negative | 17 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | 25 (100.0) |

| Sexual history with women | |||

| Age at first sexual encounter (years) | 16 (14–17; 5–22; 1056) | 16 (14–17; 6–24; 1061) | 16 (14–17; 5–24; 2117) |

| Sexual intercourse with any partner in previous 6 months | |||

| Yes | 956 (87.5) | 957 (87.6) | 1913 (87.5) |

| No | 137 (12.5) | 136 (12.4) | 273 (12.5) |

| Number of partners in previous 6 months | |||

| 0 | 137 (12.5) | 136 (12.4) | 273 (12.5) |

| 1 | 472 (43.2) | 482 (44.1) | 954 (43.6) |

| 2+ | 484 (44.3) | 475 (43.5) | 959 (43.9) |

| Number of partners over lifetime | 4 (3–7; 1–120; 1004) | 4 (3–7; 1–86; 1016) | 4 (3–7; 1–120; 2020) |

| Gave gifts or money to a woman for sexual intercourse in previous 6 months | |||

| Yes | 152 (15.8) | 180 (18.7) | 332 (17.2) |

| No | 809 (84.2) | 784 (81.3) | 1593 (82.8) |

| Drank alcohol at last time of having sexual intercourse | |||

| Yes | 117 (10.7) | 124 (11.3) | 241 (11.0) |

| No | 978 (89.3) | 969 (88.7) | 1947 (89.0) |

| Used a condom at last time of having vaginal sexual intercourse | |||

| Yes | 555 (50.7) | 525 (48.0) | 1080 (49.4) |

| No | 540 (49.3) | 568 (52.0) | 1108 (50.6) |

| Used a condom with sexual intercourse in previous 6 months | |||

| Always | 210 (21.9) | 208 (21.7) | 418 (21.8) |

| Inconsistent | 511 (53.3) | 500 (52.1) | 1011 (52.7) |

| Never | 238 (24.8) | 251 (26.2) | 489 (25.5) |

| Bathing frequency | |||

| Less than daily | 23 (2.1) | 22 (2.0) | 45 (2.1) |

| Daily | 1063 (97.9) | 1062 (98.0) | 2125 (97.9) |

Note: Sample sizes vary slightly from the number of randomized participants due to different data sources.

Data are median (IQR; range; n) for ordinal data, or n (%) for categorical data.

Prevalence of HPV infection

Baseline HPV prevalence was similar in men randomized to male circumcision (50.4%) and to control (49.7%; PRR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.93, 1.10 overall; 0.99 [0.89, 1.10] in β-globin positive samples; Table 2). At six months, HPV prevalence in the circumcision group dropped to 29.8% vs. 45.3% in the control group (PRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.58, 0.74). At 12 months, HPV prevalence was 26.6% and 48.4% in the circumcision and the control group, respectively (PRR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.49, 0.62 overall; 0.58 [0.51, 0.68] in β-globin positive samples). At 24 months, HPV prevalence was 23.7% and 41.0% in the circumcision and the control group, respectively (PRR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.50, 0.66 overall; 0.57 [0.49, 0.67] in β -globin positive samples). PRRs were similar for high-risk, low-risk, and multiple HPV infections, dropping from values near 1.0 at baseline to 0.61, 0.76, and 0.55, respectively, at 6 months and 0.55, 0.59, and 0.42, respectively, at 24 months.

Table 2:

Prevalence of HPV infection in the glans or the shaft over 24 months among 2,193 men participating in a randomized, controlled trial of male circumcision, stratified by treatment arm

| Circumcision group (N=1,096) | Control group (N=1,097) | PRR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Baseline Visit‡ | |||

| HPV DNA positive | 552 (50.4) | 545 (49.7) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10)ǂ |

| High-risk HPV positive* | 371 (35.7) | 385 (36.6) | 0.98 (0.87, 1.09) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 125 (12.0) | 115 (11.0) | 1.10 (0.87, 1.40) |

| Single HPV infections | 230 (21.0) | 231 (21.1) | 1.00 (0.85, 1.17) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 322 (29.4) | 314 (28.6) | 1.03 (0.90, 1.17) |

| 6-month visit | |||

| HPV DNA positive | 287 (29.8) | 440 (45.3) | 0.66 (0.58, 0.74) |

| High-risk HPV positive | 174 (18.3) | 290 (30.2) | 0.61 (0.51, 0.71) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 105 (11.0) | 139 (14.5) | 0.76 (0.60, 0.97) |

| Single HPV infections | 162 (16.8) | 210 (21.6) | 0.78 (0.65, 0.94) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 125 (13.0) | 230 (23.7) | 0.55 (0.45, 0.67) |

| 12-month visit | |||

| HPV DNA positive | 262 (26.6) | 479 (48.4) | 0.55 (0.49, 0.62)≠ |

| High-risk HPV positive | 151 (15.7) | 314 (32.7) | 0.48 (0.40, 0.57) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 89 (9.2) | 136 (14.2) | 0.65 (0.51, 0.84) |

| Single HPV infections | 173 (17.5) | 226 (22.9) | 0.77 (0.64, 0.92) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 89 (9.0) | 253 (25.6) | 0.35 (0.28, 0.44) |

| 18-month visit | |||

| HPV DNA positive | 270 (28.4) | 474 (49.1) | 0.58 (0.51, 0.65) |

| High-risk HPV positive | 184 (19.8) | 308 (32.3) | 0.61 (0.52, 0.72) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 65 (7.0) | 155 (16.3) | 0.43 (0.33, 0.57) |

| Single HPV infections | 170 (17.9) | 222 (23.0) | 0.78 (0.65, 0.93) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 100 (10.5) | 252 (26.1) | 0.40 (0.33, 0.50) |

| 24-month visit | |||

| HPV DNA positive | 225 (23.7) | 378 (41.0) | 0.58 (0.50, 0.66)┤ |

| High-risk HPV positive | 139 (14.8) | 244 (26.8) | 0.55 (0.46, 0.67) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 75 (8.0) | 124 (13.6) | 0.59 (0.45, 0.77) |

| Single HPV infections | 136 (14.3) | 173 (18.8) | 0.76 (0.62, 0.94) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 89 (9.4) | 205 (22.2) | 0.42 (0.33, 0.53) |

Note: n: number; %: percentage; PRR: prevalence risk ratio (circumcision vs. control arm): CI: confidence interval; HPV: human papillomavirus; HR: high-risk; LR: low-risk.

Missing follow-up HPV result in circumcision arm: 6-month (n= 132); 12-month (n=109); 18-month (n=145); 24-month (n=145)

Missing follow-up HPV result in uncircumcision arm: 6-month (n= 125); 12-month (n=107); 18-month (n=132); 24-month (n=175)

Infections with multiple HPV types were considered high-risk if one or more high-risk HPV types were detected. All other multiple infections were considered low-risk types unless they included HPVX.

All men were uncircumcised at the baseline visit,

0.99 (0.89 – 1.10) in analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples,

0.58 (0.51 – 0.68) in analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples,

0.57 (0.49 – 0.67) in analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples

Incidence of HPV Infection

The incidence of infections of any HPV type in the glans or shaft specimens over 24 months was lower in the circumcision (50.3 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 44.3, 56.9) than the control group (75.5 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 67.8, 84.0; HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.52, 0.72 overall; 0.56 [0.45, 0.70] in analyses restricted to β-globin positive samples) among those who were negative for a specific HPV type at baseline (Table 3). In this same group, rates of incident infections for high-risk HPV, low-risk HPV, HPV16/18, HPV16/18/6/11, single and multiple HPV types over 24 months were lower in the circumcision than the control group (HRs, 0.46 to 0.77). This trend was consistent when restricted to individual HPV types, albeit to different degrees (HRs, 0.37 to 0.70). Similarly, re-infection rates following baseline positivity and subsequent negativity of any HPV, high-risk HPV, single and multiple HPV types were lower in the circumcision group compared to the control group (HRs, 0.46 to 0.69), a trend that was reflected, to various degrees, by individual HPV types (HRs, 0.10 to 1.14). The HRs of reinfections of any type HPV were similar for analyses among all samples (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.54, 0.81) and those restricted to β-globin positive samples (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.50, 0.86; Table 3).

Table 3:

Incidence and reinfection of human papillomavirus (HPV) infections in the glans or the shaft over 24 months: hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of male circumcision

| Incident infections in men negative for specific HPV type at baseline | Reinfections in men positive for specific HPV type at baseline* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circumcision Arm (N=1096) | Control Arm (N=1097) | Hazard ratios (95% CI) | Circumcision Arm (N=1096) | Control Arm (N=1097) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||||

| Incident infectionsn/N | Person-Years† | Incident infectionsn/N | Person-Years† | Incident infectionsn/N | Person-Years† | Incident infectionsn/N | Person-Years† | |||

| Any HPV | 252/544 | 501.2 | 344/552 | 455.4 | 0.61 (0.52, 0.72)ǂ | 212/504 | 247.8 | 195/397 | 149.1 | 0.66 (0.54, 0.81)≠ |

| High-risk HPV | 223/669 | 634.8 | 330/666 | 600.3 | 0.58 (0.49, 0.69) | 105/356 | 192.3 | 137/340 | 140.1 | 0.57 (0.44, 0.74) |

| Low-risk HPV | 199/915 | 850.5 | 313/936 | 875.4 | 0.61 (0.51, 0.73) | 22/123 | 70.2 | 30/108 | 54.9 | 0.58 (0.33, 1.02) |

| HPV16/18 | 137/949 | 918.7 | 241/961 | 900.8 | 0.53 (0.43, 0.66) | 21/146 | 91.7 | 26/130 | 73.1 | 0.69 (0.38, 1.23) |

| HPV 16/18/6/11 | 186/892 | 850.4 | 294/919 | 853.6 | 0.60 (0.50, 0.72) | 38/201 | 124.7 | 44/166 | 91.4 | 0.66 (0.43, 1.03) |

| Single | 365/866 | 794.8 | 437/866 | 766.4 | 0.77 (0.67, 0.89) | 72/225 | 124.1 | 98/224 | 120.4 | 0.67 (0.50, 0.91) |

| Multiple | 159/774 | 740.6 | 308/738 | 718.3 | 0.46 (0.38, 0.55) | 70/315 | 184.4 | 99/279 | 122.8 | 0.46 (0.34, 0.63) |

| High-risk | ||||||||||

| HPV16 | 109/983 | 954.4 | 185/994 | 941.1 | 0.57 (0.45, 0.72) | 12/112 | 69.7 | 17/98 | 55.1 | 0.62 (0.29, 1.33) |

| HPV56 | 69/1037 | 1001.3 | 122/1027 | 982.2 | 0.54 (0.40, 0.72) | 8/57 | 35.6 | 12/67 | 35.3 | 0.76 (0.30, 1.91) |

| HPV52 | 33/1056 | 1017.1 | 64/1040 | 998.3 | 0.51 (0.33, 0.77) | 1/40 | 25.6 | 6/56 | 35.5 | 0.23 (0.03, 1.94) |

| HPV66 | 52/1040 | 1008.7 | 91/1047 | 1000.0 | 0.56 (0.40, 0.78) | 3/54 | 30.4 | 7/50 | 30.3 | 0.40 (0.10, 1.57) |

| HPV35 | 46/1038 | 1002.7 | 109/1062 | 1008.3 | 0.41 (0.29, 0.58) | 3/58 | 32.7 | 4/35 | 22.4 | 0.48 (0.10, 2.18) |

| HPV31 | 31/1053 | 1024.3 | 57/1057 | 1012.6 | 0.53 (0.34, 0.82) | 1/43 | 26.8 | 1/39 | 20.7 | --- |

| HPV18 | 56/1049 | 1016.5 | 94/1060 | 1017.4 | 0.58 (0.42, 0.81) | 2/47 | 30.7 | 4/37 | 22.0 | 0.33 (0.06, 1.87) |

| Low-risk | ||||||||||

| HPV67 | 54/1048 | 1020.7 | 99/1034 | 990.8 | 0.53 (0.38, 0.74) | 1/48 | 31.0 | 11/60 | 30.7 | 0.10 (0.01, 0.78) |

| HPV42 | 39/1045 | 1013.4 | 102/1044 | 993.7 | 0.37 (0.26, 0.53) | 4/51 | 29.7 | 4/51 | 28.2 | 0.95 (0.23, 3.85) |

| HPVJC9710 | 47/1047 | 1001.9 | 119/1050 | 1003.3 | 0.38 (0.27, 0.54) | 7/49 | 29.7 | 5/43 | 24.2 | 1.14 (0.36, 3.64) |

| HPV6 | 57/1048 | 1011.3 | 98/1059 | 1012.9 | 0.57 (0.41, 0.79) | 4/48 | 29.8 | 5/36 | 22.0 | 0.59 (0.16, 2.24) |

| HPV40 | 41/1047 | 1019.4 | 76/1055 | 1013.1 | 0.53 (0.37, 0.78) | 6/49 | 31.1 | 8/42 | 18.9 | 0.57 (0.19, 1.74) |

| HPV43 | 43/1048 | 1010.1 | 74/1054 | 1002.6 | 0.57 (0.39, 0.83) | 5/48 | 26.1 | 6/42 | 19.0 | 0.65 (0.19, 2.16) |

| HPV11 | 36/1074 | 1036.2 | 51/1076 | 1028.1 | 0.70 (0.45, 1.07) | 0/22 | 14.9 | 2/21 | 13.4 | --- |

Note. n= number of men with a type-specific incident HPV infection; N= total number of men at risk for an incident infection of the specific HPV type.

Analyses among men positive for the specific HPV type at baseline, then negative for that type during follow up. Only newly acquired (repeat infections) of the specific HPV type were considered incident infections.

Person-years were estimated by assuming that the incident HPV infection was acquired at the midpoint between the last HPV-negative result and the first subsequent HPV-positive result.

0.56 (0.45, 0.70) in analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples,

0.66 (0.50, 0.86) in analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples

--- CI width > 1,000

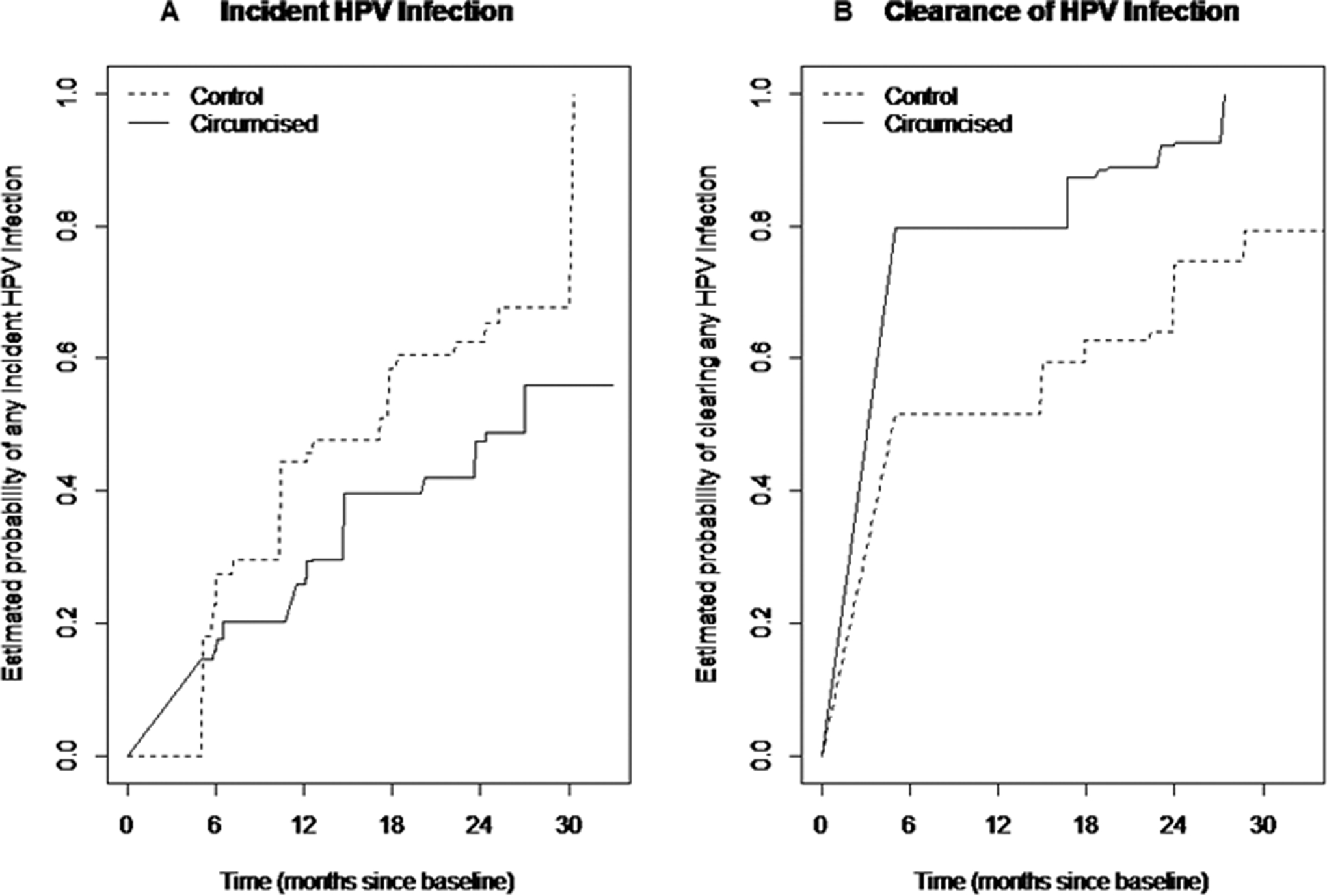

Among men who were HPV negative at baseline, those in the circumcision group were less likely to have an incident HPV infection detected at follow-up compared to the control group (24-month cumulative incidence, 47.5%; 95% CI, 43.1%-51.9% versus 62.5%; 95% CI, 58.4%-66.6%; P<0.001; Figure 1A).

Figure 1:

Kaplan Meier curve of the cumulative incidence (A) and cumulative clearance (B) of penile HPV infections in the glans or shaft specimen, stratified by randomization arm in intention-to-treat analyses

Clearance of HPV infection

The clearance rate of any HPV infection present at baseline over 24 months was higher in the circumcision group (272 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 257, 289) than in the control group (212 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 200, 225; HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.49, 2.34 overall; HR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.48, 2.66 in β-globin positive samples; Table 4). In men with prevalent HPV infection at baseline, clearance rates of low-risk HPV, high-risk HPV, HPV16/18, HPV16/18/6/11, and multiple HPV types were all higher in the circumcision than the control group (HRs, 1.50 to 1.89). This trend was reflected by common individual HPV types (except HPV35 and 6), albeit to different degrees (HRs, 1.23 to 1.89).

Table 4:

Clearance of human papillomavirus (HPV) infections in the glans or the shaft over 24 months: hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect of male circumcision

| Prevalent Infection present at baseline | Incident Infection not present at baseline | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circumcision Arm (N=1096 men) | Control Arm (N=1097 men) | Hazard ratios (95% CI) | Circumcision Arm (N=1096 men) | Control Arm (N=1097 men) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||||

| Cleared infectionsn/N | Person-Years* | Cleared infectionsn/N | Person-Years* | Cleared infectionsn/N | Person-Years* | Cleared infectionsn/N | Person-Years* | |||

| Any HPV | 1149/1160 | 421.8 | 1132/1171 | 533.6 | 1.87 (1.49, 2.34)ǂ | 814/1194 | 306.5 | 1508/2333 | 703.6 | 1.68 (1.39, 2.02)≠ |

| High-risk HPV | 598/606 | 222.9 | 613/633 | 280.5 | 1.76 (1.29, 2.39) | 431/627 | 156.8 | 735/1143 | 321.5 | 1.62 (1.25, 2.10) |

| Low-risk HPV | 551/554 | 198.9 | 521/540 | 253.1 | 1.56 (1.21, 2.00) | 383/567 | 149.7 | 773/1190 | 382.1 | 1.75 (1.33, 2.31) |

| HPV16/18 | 159/160 | 55.8 | 133/140 | 67.0 | 1.79 (1.29, 2.50) | 109/165 | 41.6 | 181/278 | 78.1 | --- |

| HPV 16/18/6/11 | 229/230 | 83.3 | 189/198 | 88.8 | 1.53 (1.17, 1.99) | 170/258 | 65.1 | 276/427 | 124.5 | 1.48 (0.99, 2.21) |

| Single | 179/180 | 69.4 | 184/193 | 90.4 | 1.50 (1.14, 1.98) | 423/606 | 161.2 | 763/1133 | 338.2 | 1.50 (1.17, 1.92) |

| Multiple | 970/980 | 352.3 | 950/980 | 443.2 | 1.89 (1.46, 2.47) | 364/554 | 148.8 | 788/1277 | 384.7 | 1.48 (1.13, 1.93) |

| High-risk | ||||||||||

| HPV16 | 112/113 | 39.9 | 96/103 | 48.7 | 1.35 (0.87–2.08)├ | 73/109 | 28.2 | 118/184 | 51.3 | 1.31 (0.88, 1.95) |

| HPV56 | 57/59 | 25.0 | 66/70 | 36.5 | 1.23 (0.77, 1.94) | 50/69 | 17.7 | 76/122 | 40.5 | 1.48 (0.90, 2.42) |

| HPV52 | 40/40 | 14.4 | 56/57 | 23.5 | 1.23 (0.66, 2.31) | 23/32 | 8.2 | 36/64 | 11.2 | --- |

| HPV66 | 54/56 | 21.4 | 50/50 | 19.6 | 1.29 (0.67, 2.49) | 31/52 | 15.8 | 58/91 | 28.6 | 1.11 (0.64, 1.94) |

| HPV35 | 58/58 | 24.3 | 35/35 | 12.9 | 0.94 (0.48, 1.82) | 30/46 | 12.2 | 68/108 | 37.8 | 2.22 (1.23, 4.00) |

| HPV31 | 43/43 | 14.1 | 39/40 | 18.2 | --- | 19/31 | 6.0 | 31/57 | 15.6 | 1.66 (0.71, 3.86) |

| HPV18 | 47/47 | 15.9 | 37/37 | 18.3 | 1.89 (1.02, 3.51) | 36/56 | 13.4 | 63/94 | 26.7 | 1.40 (0.83, 2.37) |

| Low-risk | ||||||||||

| HPV67 | 48/48 | 15.2 | 60/63 | 34.5 | 1.76 (0.99, 3.13) | 29/54 | 10.2 | 55/99 | 38.9 | 1.95 (1.07, 3.54) |

| HPV42 | 51/51 | 18.5 | 51/53 | 25.2 | 1.25 (0.71, 2.20) | 27/38 | 10.2 | 63/102 | 39.8 | 1.84 (1.01, 3.36) |

| HPVJC9710 | 49/49 | 16.8 | 43/47 | 20.6 | 1.28 (0.67, 2.46) | 39/47 | 12.3 | 72/119 | 38.6 | 1.44 (0.87, 2.39) |

| HPV6 | 48/48 | 20.3 | 36/38 | 14.5 | 0.65 (0.32, 1.29) | 40/57 | 14.3 | 59/98 | 31.9 | 0.95 (0.59, 1.54) |

| HPV40 | 49/49 | 15.2 | 41/42 | 22.2 | --- | 25/41 | 9.7 | 47/76 | 25.8 | 1.27 (0.71, 2.26) |

| HPV43 | 48/48 | 21.5 | 42/43 | 26.1 | 1.25 (0.76, 2.06) | 33/43 | 11.9 | 47/74 | 26.4 | 1.35 (0.74, 2.43) |

| HPV11 | 22/22 | 7.2 | 21/21 | 7.3 | --- | 21/36 | 9.3 | 36/51 | 14.5 | 1.64 (0.76, 3.54) |

Note. Clearance was defined as an HPV-positive result followed by an HPV-negative result for that type; n= number of cleared HPV infections; N=total number of HPV infections

Person-years were estimated by assuming that an HPV infection was cleared at the midpoint between the last HPV-positive result and the first subsequent HPV-negative result.

1.98 (1.48 – 2.66) in analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples;

1.63 (1.26 – 2.10) in analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples;

1.18 (0.69 – 2.01) in Analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples.

--- CI width > 1,000

Similarly, in men without the specific HPV type infection at baseline, clearance rates of any HPV, high-risk HPV, low-risk HPV, and multiple incident HPV infection acquired after baseline were higher in the circumcision than the control group (HRs, 1.48 to 1.75). This trend was reflected by common individual HPV types (except HPV6), albeit to different degrees (HRs, 1.11 to 2.22). The HR of clearance of incident infections not present at baseline among all samples (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.39, 2.02) was similar to analyses restricted to β-globin positive samples (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.26, 2.10; Table 4).

Among HPV infections present at baseline, the estimated time to clearance was less among men in the circumcision arm (79.7% estimated probability of clearing infection by 6 months) compared to men in the control arm (51.5% estimated probability of clearing infection by 6 months; Figure 1B).

HPV Infection by Anatomical Site

HPV prevalence was consistently higher in the glans than shaft for all HPV groupings (e.g. overall HPV prevalence at baseline in controls: 46% in glans; 17% in shaft; Table 5). In the glans, HPV prevalence was lower in the circumcision than in the control arm at all post-baseline visits and for all HPV-type groupings post-baseline (PRRs, 0.31 to 0.72), while in the shaft, no differences were observed in HPV prevalence between the circumcision and the control arm.

Table 5:

Prevalence of HPV infection over 24 months among in 2,193 men participating in a randomized, controlled trial of male circumcision, stratified by treatment arm and anatomical site

| Glans | Shaft | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circumcision Arm* (N=1,096) | Control Arm† (N=1,097) | PRR (95% CI) | Circumcision Arm* (N=1,096) | Control Arm† (N=1,097) | PRR (95% CI) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Baseline Visit‡ | ||||||

| HPV DNA positive | 495 (45.16) | 502 (45.76) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.08)≠ | 209 (19.07) | 189 (17.23) | 1.11 (0.93, 1.32)├ |

| High-risk HPV positive | 316 (30.21) | 351 (33.02) | 0.92 (0.81, 1.04) | 129 (12.02) | 125 (11.65) | 1.03 (0.82, 1.30) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 129 (12.33) | 117 (11.01) | 1.12 (0.89, 1.42) | 57 (5.31) | 40 (3.73) | 1.43 (0.96, 2.12) |

| Single HPV infections | 229 (20.89) | 222 (20.24) | 1.03 (0.88, 1.22) | 128 (11.68) | 118 (10.76) | 1.09 (0.86, 1.37) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 266 (24.27) | 280 (25.52) | 0.95 (0.82, 1.10) | 81 (7.39) | 71 (6.47) | 1.14 (0.84, 1.55) |

| 6-month visit | ||||||

| HPV DNA positive | 236 (24.56) | 409 (42.08) | 0.58 (0.51, 0.67) | 154 (15.98) | 128 (13.17) | 1.21 (0.98, 1.51) |

| High-risk HPV positive | 140 (14.63) | 263 (27.25) | 0.54 (0.45, 0.65) | 91 (9.50) | 80 (8.28) | 1.15 (0.86, 1.53) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 92 (9.61) | 139 (14.40) | 0.67 (0.52, 0.86) | 57 (5.95) | 42 (4.35) | 1.37 (0.93, 2.02) |

| Single HPV infections | 143 (14.88) | 200 (20.58) | 0.72 (0.60, 0.88) | 99 (10.27) | 84 (8.64) | 1.19 (0.90, 1.57) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 93 (9.68) | 209 (21.50) | 0.45 (0.36, 0.57) | 55 (5.71) | 44 (4.53) | 1.26 (0.86, 1.85) |

| 12-month visit | ||||||

| HPV DNA positive | 211 (21.40) | 431 (43.54) | 0.49 (0.43, 0.56) | 139 (14.08) | 159 (16.06) | 0.88 (0.71, 1.08) |

| High-risk HPV positive | 123 (12.64) | 279 (28.79) | 0.44 (0.36, 0.53) | 77 (7.91) | 88 (9.02) | 0.88 (0.65, 1.18) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 75 (7.71) | 131 (13.52) | 0.57 (0.44, 0.75) | 49 (5.03) | 57 (5.84) | 0.86 (0.59, 1.25) |

| Single HPV infections | 143 (14.50) | 213 (21.52) | 0.67 (0.56, 0.82) | 106 (10.74) | 107 (10.81) | 0.99 (0.77, 1.28) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 68 (6.90) | 218 (22.02) | 0.31 (0.24, 0.41) | 33 (3.34) | 52 (5.25) | 0.64 (0.42, 0.98) |

| 18-month visit | ||||||

| HPV DNA positive | 191 (20.13) | 430 (44.61) | 0.45 (0.39, 0.52) | 153 (16.17) | 175 (18.13) | 0.89 (0.73, 1.09) |

| High-risk HPV positive | 121 (12.98) | 263 (27.63) | 0.47 (0.39, 0.57) | 105 (11.15) | 110 (11.40) | 0.98 (0.76, 1.26) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 53 (5.69) | 155 (16.28) | 0.35 (0.26, 0.47) | 44 (4.67) | 65 (6.74) | 0.69 (0.48, 1.01) |

| Single HPV infections | 126 (13.28) | 216 (22.14) | 0.59 (0.49, 0.72) | 110 (11.63) | 117 (12.12) | 0.96 (0.75, 1.22) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 65 (6.85) | 214 (22.20) | 0.31 (0.24, 0.40) | 43 (4.55) | 58 (6.01) | 0.76 (0.52, 1.11) |

| 24-month visit | ||||||

| HPV DNA positive | 175 (18.40) | 356 (38.70) | 0.48 (0.41, 0.56) | 137 (14.42) | 127 (13.77) | 1.05 (0.84, 1.31) |

| High-risk HPV positive | 107 (11.31) | 222 (24.37) | 0.46 (0.38, 0.57) | 86 (9.13) | 70 (7.63) | 1.20 (0.88, 1.62) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 63 (6.66) | 125 (13.72) | 0.49 (0.36, 0.65) | 43 (4.56) | 52 (5.67) | 0.81 (0.54, 1.19) |

| Single HPV infections | 108 (11.36) | 173 (18.80) | 0.60 (0.48, 0.75) | 87 (9.16) | 78 (8.46) | 1.08 (0.81, 1.45) |

| Multiple HPV infections | 67 (7.05) | 183 (19.89) | 0.35 (0.27, 0.46) | 50 (5.26) | 49 (5.31) | 0.99 (0.67, 1.45) |

Note: n: number; %: percentage; PRR: prevalence risk ratio (circumcision vs. control arm): CI: confidence interval; HPV: human papillomavirus; HR: high-risk; LR: low-risk; Infections with multiple HPV types were considered high-risk if one or more high-risk HPV types were detected. All other multiple infections were considered low-risk types unless they included HPVX.

Missing follow-up HPV result in circumcision arm: 6-month (n= 132); 12-month (n=109); 18-month (n=145); 24-month (n=145)

Missing follow-up HPV result in uncircumcision arm: 6-month (n= 125); 12-month (n=107); 18-month (n=132); 24-month (n=175)

All men were uncircumcised at the baseline visit

0.95 (0.85 –1.07) in analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples;

1.08 (0.84 – 1.40) in analyses restricted to beta-globin positive samples.

Men in the circumcision group had lower incidence rates (Supplementary Table 1) and higher clearance rates (Supplementary Table 2) of HPV infection in glans samples, but not in shaft samples, although several point estimates were not reliable for individual types due to relatively small sample sizes within strata.

There were lower reinfection rates for all HPV type groupings in the circumcision compared to the control arm in the glans (HRs, 0.41 to 0.88); and for any HPV, high-risk HPV, and low-risk HPV (HRs, 0.65 to 0.71) in the shaft (Supplementary Table 3). We also observed higher HPV clearance among men with new, incident HPV infections in the circumcision group for the glans (any HPV, high-risk HPV, low-risk HPV, HPV16, and HPV56; Supplementary Table 4). Associations were relatively imprecise for both of these sub-analyses, particularly for individual HPV types.

As-treated analyses

Results for the as-treated analysis were similar to the intent to treat results. In particular, for incident infections of any HPV type over 24 months the hazard was lower when men were circumcised (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.49, 0.69). Likewise, the clearance rate of any HPV infection over 24 months was higher when men were circumcised (HR 1.50; 95% CI 1.39, 1.62)

DISCUSSION

In this large RCT of male circumcision and HPV infection, men in the circumcision group had approximately 40% lower incidence and 35% lower HPV reinfection rate over 24 months than the control group. Men in the circumcision group had an approximately 40% lower prevalence of overall, high-risk, and low-risk HPV infections for combined glans and shaft specimens than the control group at all post-baseline visits, with prevalence decreasing notably from the baseline to the six month visit and remaining relatively stable over time from 12 to 24 months. Male circumcision was associated with at least 50% higher clearance of any, high-risk, and low-risk prevalent HPV infections over 24 months, and similar clearance of newly acquired HPV infections in combined glans/shaft specimens as compared with the control group. Male circumcision was most strongly associated with lower incidence and higher clearance rates of multiple HPV type infections, with similar findings for single-type infections. The protective effect of male circumcision was consistently observed in glans specimens, but not in shaft specimens.

The results of our study are remarkably similar to those of the two other RCTs of male circumcision previously reported.11,22 Comparing point-prevalence in intention-to-treat analyses, our results for high-risk HPV comparing men in the circumcision to the control group at 24 months (PRR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.38–0.57 for glans/sulcus specimens) are not different from the PRR of 0.66 (95% CI, 0.51–0.86) observed using urethral sampling at 21-months in Orange Farm, South Africa,11 nor to the unadjusted risk ratio (RR) of 0.65 observed using glans/sulcus specimens at 24 months in Rakai.21 Estimates of HPV incidence or clearance are not available for Orange Farm.11 The RR of 0.67 (95% CI; 0.51–0.89) found in Rakai14 for male circumcision on high-risk HPV incidence in intention-to-treat analyses is somewhat lower than our observed HR of 0.48 (95% CI, 0.40, 0.57) in glans specimens. This modest difference may largely be driven by the higher incidence rate among our Kenyan control group (55.0 per 100 person-years) as compared to controls in Rakai (29.4 per 100 person-years), who were older and more likely to be married, and thus a lower risk population than the younger, mostly unmarried male participants from Kisumu.

Male circumcision had a protective effect on the incidence of multiple (HR, 0.46) and single-type (HR, 0.77) infections, in contrast to Rakai, which found a protective effect on incident high-risk multiple infections (RR glans, 0.45), but not on single-type infections (RR, 0.89; 95% CI 0.60, 1.30) in intention-to-treat analyses.14 Findings from Kisumu and Rakai showed increased high-risk HPV clearance in the circumcision group compared with the control group (HR Kisumu, 1.76; RR Rakai, 1.39).14 Both the Kisumu and Rakai results appear to differ somewhat from the observational HIM study of 4,033 men,23 which found that overall HPV incidence and persistence did not differ between circumcised and uncircumcised men; however, there were specific HPV types for which HPV incidence was lower, and clearance higher, in circumcised as compared to uncircumcised men, which is similar to our results. In the observational HIM study, associations between male circumcision and HPV incidence and clearance remained similar when the authors adjusted for sexual behavior of the participants. In our study, the effect of male circumcision on HPV incidence, clearance, and reinfection is also unlikely to be explained by changes in sexual behavior over time, as there was little difference in this aspect between the circumcision and the control group.9

This study is unique in that it examined the effect of male circumcision separately for glans/coronal sulcus and penile shaft specimens over time in an RCT setting. Until now it has been unclear whether HPV incidence differs by anatomical site.15,22,24,25 We found a strong protective effect of male circumcision on incident HPV glans infections over 24 months (HR, 0.51), but not on shaft infections (HR, 1.01; 95% CI 0.87, 1.17). This is biologically plausible, since the inner foreskin is less keratinized than the shaft and, therefore, potentially more susceptible to HPV infection.26 Furthermore, the foreskin likely creates a micro-environment that facilitates the persistence of penile HPV infection.26 Accordingly, we found more frequent clearance of HPV in the circumcision group and of reductions in HPV prevalence over the 24 months of follow-up. In light of our findings of a lack of an association between male circumcision on the incidence and clearance of HPV infections of the penile shaft, further understanding is needed of the differential transmissibility of penile HPV infections of the shaft as compared to the glans/coronal sulcus, including modelling of the likely effect of male circumcision on the transmission of HPV from men to women based on these study findings. Data from the Rakai RCT showed a protective effect of male circumcision on HPV transmission from participating men to their female partners among HIV-negative couples.27,28

As study strengths, we utilized a sensitive and validated GP5+/6+ assay ascertained 44 HPV types and allowed determination of the clearance of any HPV, including high- and low-risk HPV within an RCT. Furthermore, we present novel data on observed associations between male circumcision and the occurrence of HPV reinfections, as well as clearance of newly acquired HPV infections. Our study also has some limitations: In our results presentation, we have utilized the term ‘re-infection” to refer to those type-specific infection groups which were observed following baseline positivity and subsequent negativity; however, these also could represent reactivation of latent viral infections.29 β-globin positivity overall in glans and/or shaft samples ranged from 60–80% over study follow-up. However, we observed similar results when analyses were restricted to β-globin positive samples. The observed relatively low prevalence of β-globin positivity at baseline and follow-up are not unexpected among penile HPV exfoliated cell samples. A possible explanation is that penile cells, particularly in shaft samples, are more keratinized and anucleated than those in the cervix, and therefore may contain relatively less human DNA.18 A lower frequency of β-globin positivity in penile swab samples has also been documented in several studies of HPV in penile samples.14 Furthermore, we were not able to examine the effect of male circumcision among HIV-positive men, or among men over 26 and under 18 years of age, given study eligibility criteria.

In 2007, the World Health Organization issued recommendations to promote male circumcision for HIV prevention.30 Since then, over 27 million voluntary medical male circumcisions have been performed in 15 target countries in Eastern and Southern African.31 Male circumcision may not be protective against Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Trichomonas vaginalis infections.32 However, male circumcision is a valuable tool for HIV prevention,9–11 and can also reduce the risk of HPV incidence, re-infection and increase HPV clearance. Given our results, male circumcision should be considered effective for preventing HPV infections and may thus synergistically with HPV vaccination programs contribute to the primary prevention of penile, anal, and cervical cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Chelu Mfalila, Corette Parker and Norma Pugh for their assistance in database management, and all of the UNIM staff, especially the late Dr. Jeckoniah O. Ndinya-Achola for his leadership. We are grateful to Mary John for her contributions to the HPV testing, Martijn Boogaarts for his input in HPV analyses, and Dr. Virginia Senkomago for her assistance in reviewing the manuscript. We are also grateful to the late Prof. Peter J.F. Snijders for his contribution to the design of this study and the HPV testing of the penile swab samples.

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grant R01 CA114773–04, J.S. Smith) and the UNC Center for AIDS Research (grant 5 P30 AI050410–13 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, R. Swanstrom). The main RCT was supported by the Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (grant AI50440, R.C. Bailey), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the Chicago Developmental Center for AIDS Research (D-CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI 082151), which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NCCAM).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

J. S. Smith has received research grants and consultancies from BD Diagnostics and Hologic, and supply donations from Rovers and Arbor Vita over the past five years. D. Backes, H. Chakraborty, S. Moses, K. Agot, M.G. Hudgens, W. Mei, E.Rohner, and R. C. Bailey do not have a conflict of interest with this manuscript. CJLMM is minority shareholder and part-time CEO of Self-screen B.V., a spin-off company of AmsterdamUMC (location VUmc) which develops, manufactures and licenses the high-risk HPV assay and methylation marker assays for cervical cancer screening CJLMM has a very small number of shares of Qiagen and MDXHealth, has received speakers fees from GSK, Qiagen, and SPMSD/Merck, and served occasionally on the scientific advisory boards (expert meeting) of these companies.

References

- 1.Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update. Int J cancer 2007; 121: 621–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Backes DM, Kurman RJ, Pimenta JM, Smith JS. Systematic review of human papillomavirus prevalence in invasive penile cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2009; 20: 449–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoots BE, Palefsky JM, Pimenta JM, Smith JS. Human papillomavirus type distribution in anal cancer and anal intraepithelial lesions. Int J Cancer 2009; 124: 2375–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burchell AN, Coutlee F, Tellier P-P, Hanley J, Franco EL. Genital Transmission of Human Papillomavirus in Recently Formed Heterosexual Couples. J Infect Dis 2011; 204: 1723–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu B, Kumar A, Castellsagué X, Giuliano AR. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic vaccines against cervical HPV infection and diseases among women: a systematic review & meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbyn M, Xu L, Simoens C, Martin-Hirsch PP. Prophylactic vaccination against human papillomaviruses to prevent cervical cancer and its precursors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; published online May 9. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009069.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, et al. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. Lancet Glob Heal 2016; 4: e453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM, et al. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet (London, England) 2006; 367: 1247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 369: 643–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet 2007; 369: 657–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auvert B, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Cutler E, et al. Effect of male circumcision on the prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus in young men: results of a randomized controlled trial conducted in Orange Farm, South Africa. J Infect Dis 2009; 199: 14–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larke N, Thomas SL, dos Santos Silva I, Weiss HA. Male Circumcision and Human Papillomavirus Infection in Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Infect Dis 2011; 204: 1375–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albero G, Castellsagué X, Giuliano AR, Bosch FX. Male Circumcision and Genital Human Papillomavirus. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39: 104–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray RH, Serwadda D, Kong X, et al. Male circumcision decreases acquisition and increases clearance of high-risk human papillomavirus in HIV-negative men: a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis 2010; 201: 1455–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tobian AAR, Kong X, Gravitt PE, et al. Male circumcision and anatomic sites of penile high-risk human papillomavirus in Rakai, Uganda. Int J cancer 2011; 129: 2970–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senkomago V, Backes DM, Hudgens MG, et al. Acquisition and persistence of human papillomavirus 16 (HPV-16) and HPV-18 among men with high-HPV viral load infections in a circumcision trial in Kisumu, Kenya. In: Journal of Infectious Diseases. Oxford University Press, 2015: 811–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith JS, Moses S, Hudgens MG, et al. Human papillomavirus detection by penile site in young men from Kenya. Sex Transm Dis 2007; 34: 928–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JS, Backes DM, Hudgens MG, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of human papillomavirus infection by penile site in uncircumcised Kenyan men. Int J cancer 2010; 126: 572–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Brule AJC, Pol R, Fransen-Daalmeijer N, Schouls LM, Meijer CJLM, Snijders PJF. GP5+/6+ PCR followed by reverse line blot analysis enables rapid and high-throughput identification of human papillomavirus genotypes. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40: 779–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snijders P, van den Brule A, Jacobs M. HPV DNA detection and typing in cervical scrapes by general primer GP5+/6+ PCR. In: Davy C,JD, eds. Methods in Molecular Medicine: Human papillomaviruses— Methods and Protocols. 2005: 101–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wellner JA, Zhan Y. A Hybrid Algorithm for Computation of the Nonparametric Maximum Likelihood Estimator From Censored Data. J Am Stat Assoc 1997; 92: 945. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobian AAR, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, et al. Male Circumcision for the Prevention of HSV-2 and HPV Infections and Syphilis. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 1298–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albero G, Castellsagué X, Lin H-Y, et al. Male circumcision and the incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in men: the HPV Infection in men (HIM) cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castellsagué X, Bosch FX, Muñoz N, et al. Male Circumcision, Penile Human Papillomavirus Infection, and Cervical Cancer in Female Partners. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 1105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez BY, Wilkens LR, Zhu X, et al. Circumcision and human papillomavirus infection in men: a site-specific comparison. J Infect Dis 2008; 197: 787–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCoombe SG, Short RV. Potential HIV-1 target cells in the human penis. AIDS 2006; 20: 1491–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabowski MK, Gravitt PE, Gray RH, et al. Trends and determinants of human papillomavirus concordance among HIV-positive and HIV-negative heterosexual couples in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis 2016; 215: jiw631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wawer MJ, Tobian AAR, Kigozi G, et al. Effect of circumcision of HIV-negative men on transmission of human papillomavirus to HIV-negative women: a randomised trial in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet (London, England) 2011; 377: 209–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pamnani SJ, Sudenga SL, Rollison DE, et al. Recurrence of genital infections with 9 human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine types (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) among men in the HPV infection in Men (HIM) study. J Infect Dis 2018; 218: 1219–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.New data on male circumcision and HIV prevention: policy and programme implications. 2007. http://who.int/hiv/mediacentre/MCrecommendations_en.pdf.

- 31.UNAIDS/WHO. Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision: steady progress in the scaleup of VMMC as an HIV prevention intervention in 15 eastern and southern African countries before the SARS-CoV2 pandemic. Progress Brief February 2021. https://www.malecircumcision.org/file/unaids-who-vmmc-progress-brief-16feb2021webpdf

- 32.Mehta SD, Moses S, Agot K, et al. Adult male circumcision does not reduce the risk of incident Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, or Trichomonas vaginalis infection: Results from a randomized, controlled trial in Kenya. J Infect Dis 2009; 200: 370–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.