Abstract

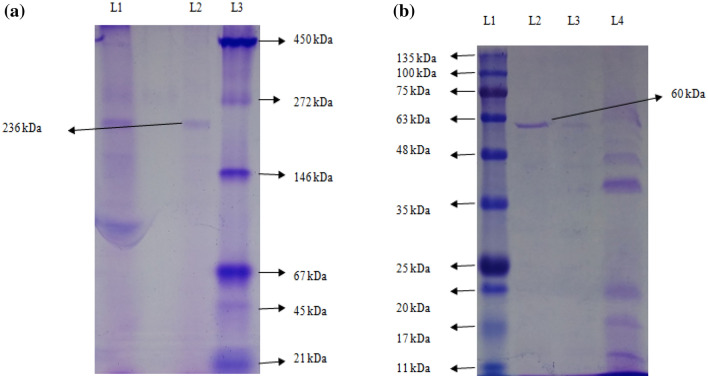

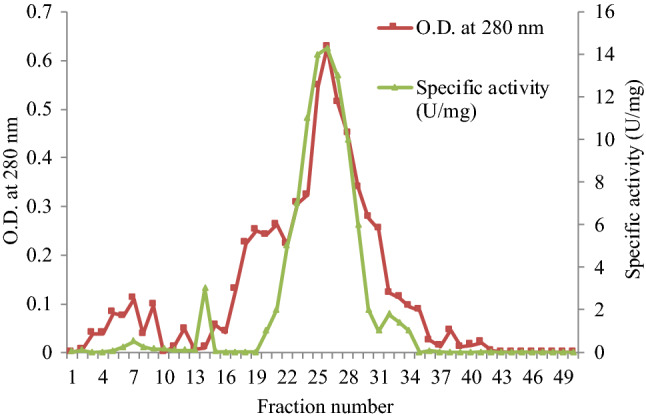

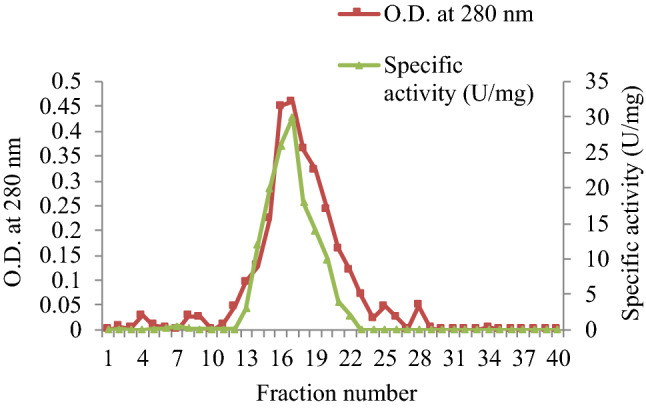

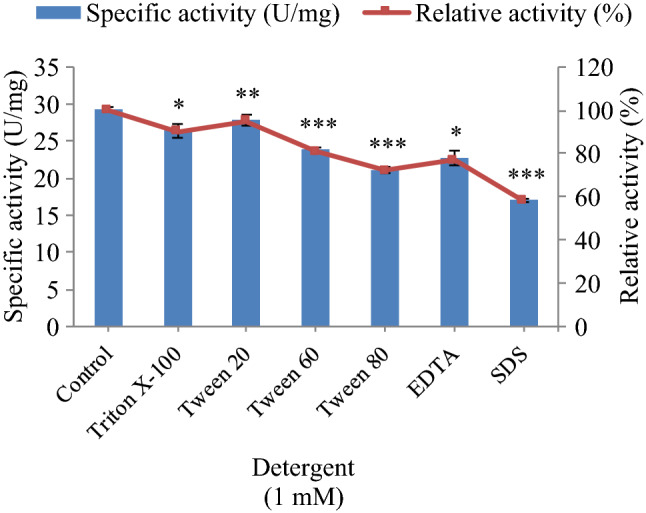

In the present study, an extracellular esterase from Serratia sp. was purified 24.46 fold using an initial ammonium sulphate precipitation step (optimized concentration of 30–40%), followed by Diethylaminoethyl cellulose (DEAE-cellulose) chromatography and size exclusion Sephadex G-200 column chromatography steps. The molecular weight of the esterase using native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was determined to be 236 kDa and by using sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was found to be 60 kDa suggesting that the enzyme was a tetramer of 4 subunits. The purified esterase was able to catalyze the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl esters, especially p-nitrophenyl acetate. Maximum esterase activity was achieved in 0.15 M Tris–HCl buffer of pH 8.5 at 50 °C after 10 min. The enzyme was stable for at least 8 h at 4 and 35 °C but the half-life was determined to be 4.5 h at 50 °C and 3 h at 60 °C. The esterase activity was inhibited by detergents (1 mM) (Triton X-100, Tween 60, Tween 80, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid and SDS) except Tween 20. The esterase activity was inhibited by organic solvents (1 mM) such as ethanol, methanol, acetone, acetonitrile and was stable in the presence of glycerol, isopropanol but the organic solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) significantly (p < 0.05) enhanced esterase activity. The matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry showed that the enzyme exhibited similarity with the pimeloyl-[acyl carrier protein] methyl ester esterase of Serratia marcescens.

Keywords: Diethylaminoethyl cellulose, Tris–HCl buffer, p-NPA, SDS-PAGE, Esterase, Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry

Introduction

Esterases play a dominant role in lipid metabolism in plants, animals, and microbes (Castro et al. 2018). A large number of microbes are known to produce esterases and include Micropolyspora faeni, Bacillus pumilis, E. coli, B. subtilis, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Halobacillus sp. strain LY5, Bacillus subtilis NRRL, Vibrio fischeri, Streptomyces lividans 66, Bacillus licheniformis. Esterases are of considerable interest as they have large numbers of industrial applications, can be produced relatively quickly due to the fast microbial growth rates and can be cheaply produced due to the ease of culturing microbes on cheap medium (Kulkarni et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2020).

Under natural conditions, esterases catalyze the hydrolysis of ester bonds at the interface between an insoluble substrate phase and the aqueous phase in which the enzyme is dissolved. Under certain experimental conditions, such as in the absence of water, they are capable of reversing the reaction. These enzymes have good chemo-, regio-, and/or enatio-selectivity (Gupta et al. 2012). Esterase plays a major role in the degradation of natural materials and industrial pollutants, viz., cereal wastes, plastics, and other xenobiotic compounds (Bhardwaj et al. 2020; Wei et al. 2020). The enzyme has the potential for the synthesis of flavor esters (Bhardwaj et al. 2017; Zwane et al. 2017; Maester et al. 2020), optically pure compounds, antioxidants and perfumes (Panda and Gowrishankar 2005).

Esterases have diverse applications in biotechnology as additives in laundry detergents and as stereo-specific biocatalysts in pharmaceutical production (Panda and Gowrishankar 2005). Esterases differ in their substrate specificity and can be used in various medical applications (Kumari et al. 2021). However, most industrial processes often require aggressive conditions, which can lead to the inactivation of the enzymes. In this sense, novel esterases with better catalytic efficiency and specific properties suitable for special reaction conditions are highly demanded (Rao et al. 2009). Thermostability is an important property of an enzyme due to its proposed biotechnological applications. A highly active cross-linked enzyme aggregate from a novel thermostable esterase estUT1 of the bacterium Ureibacillus thermosphaericus has been used for the removal of malathion from waste water (Samoylova et al. 2018).

Due to the necessity of high purity of enzymes, different strategies for the purification of enzymes have been investigated by researchers by exploiting specific characteristics of the target biomolecule. Laboratory scale purification for esterase includes various combinations of ion exchange, gel filtration, hydrophobic interactions, and reverse phase chromatography (Wang et al. 2019). The main objective of the present study was to purify the esterase from Serratia sp. using a simple method and to study the optimum reaction conditions of the enzyme so that it could be employed in various biotechnological applications.

Materials and methods

Biological material

The bacterial isolate was previously isolated from the soil contaminated with plastic wastes, oil, sweet shop waste, dairy soil from Hamirpur, Shimla and Solan districts of Himachal Pradesh, India. The isolate was characterized by16S rRNA gene sequencing and was identified as Serratia sp. EST-4 (NCBI Accession no.: MH538970) (Bhardwaj et al. 2020).

Chemicals

Tributyrin (purity-98.5%), p-nitrophenyl acetate (p-NPA) (purity-98%), p-nitrophenol (p-NP) (purity-98%), isopropanol (purity-99.9%), Tris buffer (purity-99.8%), DMSO (purity-99.7%), sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) (purity-98%) and all other chemicals were either procured from Himedia Laboratory Ltd., Mumbai, India or Sigma Aldrich (U.S.A.).

Production of esterase

The bacterial isolate Serratia sp. EST-4 was aseptically transferred to culture broth to produce seed culture. It was incubated at 40ºC with continuous shaking at 120 rpm for 18 h. Seed culture (1.0%) of the bacterial isolate was separately inoculated in 50 ml of the sterile production medium containing 4.0% cottonseed oil as a sole source of carbon in an Erlenmeyer flask (250 ml). The flask was incubated at 40ºC with continuous shaking at 120 rpm for 48 h.

Assay of esterase enzyme

Esterase activity was determined by measuring the micromoles of p-nitrophenol (p-NP) released from p-nitrophenyl acetate (p-NPA) per min under standard assay conditions (Immanuel et al. 2010).

The protein was estimated by dye-binding method (Bradford 1976) using standard bovine serum albumin (BSA). One unit of specific activity was defined as the activity of the enzyme in units per mg of protein.

Enzyme purification

Ammonium sulphate precipitation

The production of esterase from Serratia sp. was carried out under optimized conditions and crude enzyme extract was precipitated using ammonium sulphate salt. Ammonium sulphate was gradually added to the crude extract in different fraction ranges (0–30, 30–60 and 60–90%) with constant stirring at 4 °C in a refrigerator and the mixture was allowed to stand overnight. The enzyme solution was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C and the precipitates thus obtained were reconstituted in a minimum volume of 0.15 M Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.5). The supernatant and reconstituted precipitated fractions were analyzed separately for esterase activity, protein content, and specific activity.

Dialysis

The protein precipitates were extensively dialyzed against Tris–HCl buffer (0.15 M, pH 8.5) at a regular interval of 3 h to completely remove ammonium sulphate. Finally, the dialyzate was assayed both for protein content and esterase activity followed by storage at -20ºC until further use.

Ion exchange chromatography

Purification of esterase on DEAE-Cellulose column

The concentrated sample was applied to a DEAE-Cellulose matrix column (22 × 1.25 cm) pre-equilibrated with 0.15 M Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.5) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Initial 10 fractions (2 ml each) were collected with 0.15 M Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.5) and other 40 fractions were collected with the stepwise gradient of 0.1 M NaCl, 0.3 M NaCl, 0.5 M NaCl and 0.7 M NaCl. The absorbance of all the fractions was taken at 280 nm using LabIndia 3000+ UV/VIS spectrophotometer.

Gel filtration chromatography

Sephadex G-200 column chromatography

The gel permeation chromatography was performed by using Sephadex G-200 (stationary phase-dextran) matrix packed in a column of 22 × 1.25 cm size. The pre-swollen matrix of Sephadex G-200 was packed in a column after making its slurry and poured into the column with help of a glass rod. The matrix was allowed to settle overnight and then it was equilibrated. One half-column volume of filtered distilled water was passed through the column at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The two-column volumes of 0.15 M Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.5) were made to pass through the column for washing. The enzyme fractions showing maximum specific activity from DEAE-cellulose column chromatography were pooled, concentrated by lyophilization, and loaded onto the Sephadex G-200 matrix packed column. 40 fractions, each of 2 ml were collected with 0.15 M Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.5) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The absorbance of fractions was measured at 280 nm. The fractions showing maximum esterase activity were pooled for further studies. The specific activity of the purified enzyme was compared with that of the crude enzyme and fold purification was calculated.

Molecular weight determination

For native-PAGE, 5 µl of sample loading buffer was mixed with 20 µl of the sample in an Eppendorf tube. Genie medium molecular weight marker (range 450 kDa to 21 kDa) and the sample loading buffer (1:1, v/v) were mixed properly in another Eppendorf tube and loaded onto the gel. For SDS-PAGE, 5 µl of SDS sample loading buffer was mixed with 20 µl of the sample (1:5, v/v) and it was kept in a boiling water bath for 5–10 min and then it was instantly cooled. In another Eppendorf tube BR BIOCHEM BLUeye prestained SDS protein marker (range 135–11 kDa) and sample loading buffer (1:1) were prepared by mixing properly. Samples were run at a constant voltage of 100 V at 150 mA for 3 h by keeping at 4ºC. The gel was run till the dye reached the bottom of the gel.

Characterization of the purified esterase from Serratia sp.

Selection of buffer system for maximum activity of purified esterase from Serratia sp.

To study the effect of buffers (0.15 M) on esterase activity, different buffers (sodium citrate pH 6.0, potassium phosphate pH 7.0, sodium phosphate pH 7.5, Tris–HCl pH 8.5, glycine–NaOH pH 10.0) were used separately in the reaction mixture and the esterase activity was assayed by standard method.

Effect of pH of Tris–HCl buffer and reaction temperature on activity of purified esterase from Serratia sp.

Tris–HCl buffer (0.15 M) with pH values ranging from 7.0 to 10.5 (each with a difference of 0.5) was used to perform the reaction of the enzyme, enzyme activity was then determined. To study the effect of reaction temperature on esterase activity, the reaction was carried out at different temperatures (30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 and 65 °C). Esterase activity at each of the selected temperature(s) was determined under the above-optimized conditions.

Effect of substrate specificity of purified esterase from Serratia sp.

The effect of various substrates (10 mM each of p-nitrophenyl palmitate (p-NPP), p-nitrophenyl butyrate (p-NPB), p-nitrophenyl acetate (p-NPA), p-nitrophenyl benzoate (p-NPBenz), p-nitrophenyl formate (p-NPF), p-nitrophenyl octanoate (p-NPO), p-nitrophenyl laurate (p-NPL) and p-nitrophenyl caprylate (p-NPC) on esterase activity was studied and enzyme activity was measured under optimized conditions.

Stability of purified esterase from Serratia sp.

Purified esterase was incubated at different temperatures i.e., 4, 35, 50, and 60 °C for a period of 8 h. The esterase was assayed after the interval of 1 h till 8 h by standard assay method under above-optimized conditions.

Effect of metal ions and detergents on hydrolytic activity of esterase

The effect of metal ions on the activity of the purified enzyme was studied by pre-incubating the enzyme in solutions of different metal ions Mg2+, Na+, Pb+, Co2+, Hg2+, Fe3+, Ca2+, Cu2+, K+, and Zn2+ at 1 mM final concentration in the reaction buffer (pH 8.5; 0.15 M Tris–HCl). The esterase activity in each case was determined with respect to the control (without metal ion/inhibitor).

Effect of various detergents (1 mM) (Triton X-100, Tween 20, Tween 60, Tween 80, EDTA and SDS) was studied by adding each of the detergents at a final concentration of 1 mM along with purified esterase in the reaction mixture. The esterase activity in each case was determined with respect to the control (without detergents).

Effect of different organic solvents on hydrolytic activity of esterase

The effect of various solvents (1 mM) like DMSO, ethanol, glycerol, isopropanol, methanol, acetone, and acetonitrile was studied on purified esterase activity. Each of the solvent was incubated with a purified enzyme in a volumetric ratio of 1:1 (Enzyme: organic solvent). The enzyme activity was assayed by standard method and compared with respect to control (without organic solvent).

In-silico structure prediction of purified esterase

The purified esterase from Serratia sp. was analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) at CSIR-Institute of Himalayan Bioresource Technology (CSIR-IHBT), Palampur (India). The mass/charge (m/z) values of purified esterase from Serratia sp. obtained by MALDI-TOF–MS were searched in MASCOT search engine (http://www.matrixscience.com) to obtain information about the similarity of sequence (Kumar et al. 2020; Sharma et al. 2018). The Blast at NCBI (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) was used to identify the close homology and to identify the template for modelling the 3-D structure of the target protein. The protein model was generated using SWISS MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) server, 3-D structure was predicted and further structure analysis was performed where the end result of MALDI-TOFMS was mapped to identify potential functional sites.

Statistical analysis

Standard Deviation (S.D.) was calculated from the data obtained for three replicates of the parameters studied and the Student’s t test was applied.

Results

Crude enzyme

The production of esterase from Serratia sp. showed that crude enzyme extract had enzyme activity of 11.16 U/ml with a protein content of 9.38 mg/ml. The specific activity was 1.19 U/mg (Table 1). In a previous study, the total activity of esterase from Geobacillus sp. TF17 was found to be 24.4 U with a total protein content of 42 mg and specific activity of 0.58 U/mg (Ayna et al. 2013). However, in another study, the total activity of esterase from Salimicrobium sp. LY19 was 1020 U with a total protein content of 57.1 mg and specific activity of 17.9 U/mg (Xin and Ying 2013).

Table 1.

Purification of an esterase from Serratia sp.

| Purification steps | Total esterase activity (U) | Total protein content (mg) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Purification fold | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude esterase | 1619 | 1360 | 1.19 | 1 | 100 |

| Ammonium sulphate precipitation | 545 | 175 | 3.11 | 2.61 | 33.65 |

| DEAE-Cellulose chromatography | 205 | 14.4 | 14.25 | 11.97 | 12.67 |

| Sephadex G-200 chromatography | 178 | 6.12 | 29.11 | 24.46 | 11 |

Purification of esterase from Serratia sp.

Ammonium sulphate precipitation

At 30–40% saturation of ammonium sulphate, a maximum enzyme activity of 11.85 U/ml, protein content of 3.8 mg/ml and specific activity of 3.11 U/mg of protein and a fold purification of 2.61-fold was achieved.

Purification of esterase on DEAE-Cellulose column

When the dialyzed sample (12.54 U/ml) was run on DEAE-Cellulose column, the purified fractions 22–29 showed maximum specific activity (Fig. 1). In a previous study, esterase from Vibrio fischeri was precipitated in 1 N HCl and was eluted by DEAE-Cellulose column chromatography; the enzyme showed maximum activity in fractions between 28 and 30 (Kumar and Ranjitha 2009).

Fig. 1.

Elution profile of purified esterase from Serratia sp. after DEAE-Cellulose column chromatography. 22–29 fractions showed maximum absorbance at 280 nm and specific activity

Purification of esterase on Sephadex G-200 column chromatography

When the pooled enzyme fractions obtained from DEAE-Cellulose column chromatography were concentrated and run on Sephadex G-200 column, the purified fractions 13–21 showed maximum specific activity (Fig. 2). A purification of 11.97-fold after DEAE-Cellulose chromatography and 26.83-fold after Sephadex G-200 column chromatography was observed (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Elution profile of purified esterase from Serratia sp. after Sephadex G-200 column chromatography. 13–21 fractions showed maximum absorbance at 280 nm and specific activity

Molecular weight determination

Native-PAGE analysis gave a single band of approximately 236 kDa (Fig. 3a) and SDS-PAGE analysis gave a single band of 60 kDa (Fig. 3b). This indicated that the enzyme was purified to homogeneity and was a tetramer. In a different study, esterase from Microbacterium sp. 7-1 W had a molecular weight of 600 kDa when purified by gel filtration chromatography on a Sepharose CL-6 B (Honda et al. 2002). An esterase from B. pumilus, purified by size exclusion chromatography exhibited a molecular weight of170 kDa by native PAGE and 10 kDa by SDS-PAGE (Sharma et al. 2016). In a recent study, it was found that FrsA protein from Vibrio vulnificus as esterase had a subunit molecular weight of 45 kDa as obtained by SDS-PAGE (Wang et al. 2019).

Fig. 3.

a Native-PAGE of a purified esterase from Serratia sp. L 1: dialyzed esterase enzyme, L 2: Purified esterase enzyme, L 3: SERVA Native protein marker (high range molecular weight). b SDS-PAGE of a purified esterase from Serratia sp. L 1: BR BIOCHEM BLUeye prestained SDS protein marker (medium range molecular weight), L 2,3: purified esterase enzyme, L 4: dialyzed esterase enzyme

Characterization of the purified esterase from Serratia sp.

Selection of buffer system

The maximum esterase activity (29.16 ± 0.21U/mg) was observed with 0.15 M Tris–HCl buffer of pH 8.5 (Table 2). These results indicate that esterase from Serratia sp. gave optimum activity with buffers of alkaline pH range and very low activity with buffers of acidic pH range. Buffers serve to adjust and stabilize the desired pH during the enzyme assay and the interaction between inorganic ions sometimes makes it easier for a substrate molecule to locate or bind to the active site of the enzyme (Bisswanger 2014).In an earlier study also, the maximum activity of esterase from Psychrobacter cryohalolentis K5 was observed in Tris–HCl buffer at pH 8.5 (Novototskaya-Vlasova et al. 2012).

Table 2.

Effect of buffer system on the activity of purified esterase from Serratia sp.

| Buffer (0.15 M) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium citrate (6.0) | 21.49 ± 0.20 | 74 |

| Potassium phosphate (7.0) | 17.65 ± 0.41 | 61 |

| Sodium phosphate (7.5) | 23.42 ± 0.50 | 80 |

| Tris–HCl (8.5) | 29.16 ± 0.21 | 100 |

| Glycine–NaOH (10.0) | 21.74 ± 0.20 | 75 |

Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments

Effect of pH of Tris–HCl buffer and reaction temperature

Maximum esterase activity was obtained at pH 8.5 of Tris-HCl buffer (Fig. 4a). As the pH of Tris–HCl buffer was increased from 7.5 to 8.5, a sharp increase in the activity of esterase from Serratia sp. was observed. However, a further increase in pH from 8.5 to 10.5 of Tris–HCl buffer led to a continuous decrease in enzyme activity. Probably, high pH reduced the enzyme activity remarkably due to the change of the enzyme’s spatial structure and conformation. Enzymes give maximum activity at their optimum pH, however, a change in pH might denature the enzyme and may result in a loss of activity.In contrary to our results, esterase from human-derived Lactobacillus fermentum LF-12 was found to have optimal activity at acidic pH i.e., 6.5 (Liu et al. 2020). Aaeo1 and Aaeo2 (esterases isolated from Aquifex aeolicus) both had the optimum pH at 8.0. Similar to other thermophilic esterases, both Aaeo1 and Aaeo2 tend to play a catalytic role in a slightly alkaline environment (Yang et al. 2016).

Fig. 4 a.

Effect of pH of Tris–HCl buffer on the activity of purified esterase from Serratia sp. 0.15 M concentration of Tris–HCl buffer was used. p-NPA was used as substrate to monitor ester hydrolysis. Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments. b Effect of incubation temperature on the activity of purified esterase from Serratia sp. p-NPA was used as a substrate to monitor ester hydrolysis. Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments

While studying the effect of temperature, maximum enzyme activity was observed at 50 °C (Fig. 4b); on further increase in temperature from 50–60 °C, a decline in enzyme activity was observed. At higher temperatures the structure of the enzyme alters because it becomes more flexible to open up its active site for the maximal binding with the substrate or may be due to the enzyme denaturation. In corroboration with the present study, esterase from Bacillus licheniformis was found to have an optimal activity at 50 °C and it retained 60% of its original activity at 60 °C (Wang et al. 2019). In another study, the optimal temperature of feruloyl esterase purified from Lactobacillus sp. enzyme ranged from 45 to 50 °C (Xu et al. 2017).

Effect of substrate specificity

The purified esterase had the highest affinity towards p-NPA (Table 3). Complementary shape, charge and hydrophilic/hydrophobic characteristics of enzymes and substrates are responsible for substrate specificity. In the present study, despite purified esterase ability to hydrolyze substrates with different acyl chains, it showed a preference for substrates with shorter chain lengths. In view of these findings, the enzyme from Serratia sp. can be classified as an esterase rather than lipase, since esterases show a preference for shorter short-chain p-NP esters, while lipases act more efficiently on esters with long-chain p-NP esters (Maester et al. 2020; Sarkar et al. 2020). In a previous study, a pronounced decrease in the activity of esterase produced by Geodermatophilus obscurus G20 was observed for para-nitrophenyl butyrate (Jaouani et al. 2012). The recombinant enzyme Aaeo1, showed higher activity towards short- or long-chain p-NP esters (p-NPC 4, p-NPC 5, p-NPC 16) and triacylglycerol (triacetin, triolein) than medium-chain esters, and had little activity towards olive oil (Yang et al. 2016). An esterase from halotolerant isolate, Salimicrobium sp. LY19 exihibited maximum activity towards para-nitrophenyl butyrate (p-NPB) (Xin and Ying 2013). In another study, a cold-adapted esterase isolated from Mao-tofu metagenome exhibited a maximum activity towards p-NPB at 18 °C and pH 6.5 (Fan et al. 2017).

Table 3.

Effect of different substrates on activity of purified esterase from Serratia sp.

| Substrate (10 mM) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| p-NPP | 16.64 ± 0.23 | 57 |

| p-NPB | 24.33 ± 0.17 | 83 |

| p-NPA | 29.2 ± 0.32 | 100 |

| p-NPBenz | 22.31 ± 0.24 | 76 |

| p-NPF | 25.98 ± 0.38 | 89 |

| p-NPO | 17.16 ± 0.1 | 59 |

| p-NPL | 19.39 ± 0.15 | 66 |

| p-NPC | 21.78 ± 0.28 | 75 |

Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments

Stability of purified enzyme at different temperatures

It was observed that at 4 °C and at 35 °C the enzyme activity was almost stable for about 8 h of incubation. However, at 50 °C the half-life of esterase was observed to be approximately 4.5 h and at 60 °C the half-life was found to be approximately 3 h (Fig. 5). Assuming the enzyme is stable at elevated temperatures, the productivity of the reaction can be enhanced greatly by operating at a relatively high temperature. Consequently, thermal stability is a desirable characteristic of esterases (Janssen et al. 1994). The half-time (T1/2) of WT, A134T and V160T marine esterases purified from Aspergillus fumigatus at 50 °C was approximately 5 min, 10 min and 20 min, respectively (Zhang et al. 2014). In another study, an esterase from Bacillus aryabhattai B8W22 when incubated at 20 and 30 °C for 2 h retained 86 and 80% of maximum activity and its residual activity was approximately 35% when enzyme was incubated at 40 °C, and nearly inactivated at 50 °C (Zhang et al. 2019).

Fig. 5.

Stability of purified esterase from Serratia sp. The esterase activity was determined at different temperatures i.e., 4, 35, 50, and 60 °C over a period of 8 h at intervals of 1 h. The assay was performed in 0.15 M Tris–HCl buffer of pH 8.5 using p-NPA as substrate. Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments

Effect of metal ions and detergents on the hydrolytic activity of esterase from Serratia sp.

All the metal ions studied had an inhibitory effect on esterase activity. In particular, the addition of 1 mM Mg2+, Pb+, Co2+, Fe3+, Ca2+, Cu2+, K+ and Zn2+ had little effect on the esterase activity. However, the decrease in enzyme activity was significant with 1 mM Na+ (p < 0.05) and Hg2+ (p < 0.001) as compared to control (Table 4). It is probably because the esterase enzyme does not require any cofactor. Salt ions normally act as cofactors or in some cases act as competitive inhibitors also. Either they enhance or suppress the enzyme activity. Metals in metalloenzymes act as electrophilic catalysts, stabilizing the increased electron density or negative charge that can develop during reactions. Binding of metal ions imparts major conformational rearrangement on the enzyme. In a recent study, all the metal ions (Fe3+, Mg2+, Hg2+ and Na+) had a significant inhibitory effect on the activity of crude from Bacillus licheniformis (Bhardwaj et al. 2020).In another study, esterase purified from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia OUC_Est10 showed enhanced activity in the presence of Ca2+ and K+ but inhibited activity by Cu2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Mg2+ and Fe3+ (Gao et al. 2019).

Table 4.

Effect of metal ions on the activity of esterase from Serratia sp.

| Metal ion (1 mM) | Specific activity (U/ml) | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 29.31 ± 0.29 | 100 |

| Mg2+ | 28.83 ± 0.54** | 98 |

| Na+ | 22.81 ± 0.73* | 78 |

| Pb+ | 28.12 ± 0.42** | 96 |

| Co2+ | 24.73 ± 0.69** | 84 |

| Hg2+ | 21.06 ± 0.22*** | 72 |

| Fe3+ | 24.76 ± 0.46** | 84 |

| Ca2+ | 29.03 ± 0.59** | 99 |

| Cu2+ | 24.06 ± 0.35*** | 82 |

| K+ | 28.53 ± 0.87* | 97 |

| Zn2+ | 24.31 ± 0.21*** | 83 |

Relative activities were expressed as percentages of control activity (without metal ion) plotted for each metal ion. Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 as compared to control

All the selected detergents Triton X-100, Tween 20, Tween 60, Tween 80, EDTA and SDS, had an inhibitory effect on esterase (Fig. 6). The most significant (p < 0.001) effect was found in the case of SDS and Tween 80. The non-ionic detergents seemed to weaken the hydrophobic interactions within the protein, causing disaggregation and thus enhancing its activity. Detergents, in general, have a close resemblance to esterase substrates i.e., when exceeding their solubility concentrations they form micelles and thus hinder the accessibility of substrate to the active site of the enzyme. Ionic detergents usually denature enzymes through disruption of their structure. Further non-specific associations of hydrophobic groups disrupt substrate binding and finally lead to enzyme inactivation. As per the previous study, the esterase activity from Bacillus aryabhattai B8W22 was promoted in detergents like 0.1% (w/v) NP 40, Tween 80 and Trtion-X 100 and was inhibited in the presence of SDS, EDTA and urea (Zhang et al.2019).

Fig. 6.

Effect of detergents on the activity of purified esterase from Serratia sp. p-NPA was used as a substrate to monitor ester hydrolysis. Relative activities were expressed as percentages of control activity (without detergent) plotted for each detergent. Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 as compared to control

Relative activities were expressed as percentages of control activity (without metal ion) plotted for each metal ion. Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 as compared to control.

Effect of different organic solvents on hydrolytic activity of esterase from Serratia sp.

In the present study, the enzyme showed a significant (p < 0.05) increase in catalytic activity in the presence of DMSO as compared to control (Fig. 7) however, all other solvents except glycerol had moderately inhibited the enzyme activity. The use of organic solvent tolerant lipolytic enzymes in organic media has exhibited many advantages: increased activity and stability, regiospecificity and stereoselectivity, higher solubility of substrate, ease of products recovery and ability to shift the reaction equilibrium toward a synthetic direction (Boekema et al. 2007). The solvent may enhance enzyme activity without causing any denaturation by modifying the oil–water interface. The solvent showing a negative effect on esterase activity might have distorted the active site of the enzyme, thus preventing the substrate from accessing the enzyme active site efficiently. In a previous study, esterase isolated from Bacillus sp. was highly stable in the presence of butyl-alcohol, glycerol, acetonitrile, pyridine and urea. However, the presence of acetone, methanol, trichloromethane, petroleum ether, hexane, tert-butanol, iso-propanol and benzene had inhibited the enzyme activity significantly (Li and Liu 2017).

Fig. 7.

Effect of different solvents on the activity of esterase from Serratia sp. p-NPA was used as a substrate to monitor ester hydrolysis. Relative activities were expressed as percentages of control activity (without metal ion) plotted for each organic solvent. Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 as compared to control

In-silico structure prediction analysis of purified esterase

The protein fragments obtained from MALDI-TOF–MS followed by Mascot search analysis showed the highest score (67) and mass (27,958 Da) with pameloyl- [acyl carrier protein] methyl ester esterase (Serratia marcescens) covering 34% protein sequence coverage (Fig. 8a). A higher score in MASCOT indicated that more peptides were identified from a particular protein (Sharma et al. 2018). A template-based modeling (homology modeling or comparative modeling) approach was performed to predict 3-D structure of esterase (125 residues; PDB id: 1M33) of Serratia sp. By submitting the sequence to SWISS MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) server, 3-D structure of esterase was predicted (Fig. 8b) and further structure analysis revealed three active site residues namely serine, aspartate, histidine. As the in-silico analysis revealed the presence of active site residues, it can be claimed that in purified esterase, active site residues maintained the spatial geometry for optimal esterase activity. Previously, esterases in the α/β-hydrolase fold-family had a serine-histidine-aspartate catalytic triad evolved to efficiently operate on substrates with diverse physicochemical properties (Hotelier et al. 2004).In a similar study, amino acid sequence analysis of esterase from Vibrio sp. GMD509 showed that the active site sequence motif within esterases was highly conserved and the catalytic triad was composed of Ser, Asp and His (Park et al. 2007).

Fig. 8.

a MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of tryptic digested peptides of purified esterase from Serratia sp. b 3-D structure of esterase from Serratia sp. predicted using SWISS MODEL and active site residues i.e.,serine (green), aspartate (blue), histidine (red)

Conclusion

Industrial production requires enzymes with high thermal stability to minimize enzyme consumption and increase enzyme catalytic efficiency. In this study, a simple method was used to purify the esterase, and the molecular weight of the enzyme was found to be 236 kDa and it was a tetramer. The characterization of the esterase in this study provided useful information about its function; purified esterase showed activity towards a wide range of p-nitrophenyl esters especially p-nitrophenyl acetate. The enzyme was stable at high temperature, the half-life of esterase was 4.5 h and 3 h at 50 and 60 °C respectively and it showed maximum activity in alkaline conditions. The enzyme was stable in the presence of some metal ions such as Mg2+, Pb+, Ca+, K+ and organic solvent DMSO enhanced enzyme activity. These properties of the enzyme suggest the novelty of esterase and have high potential in biotechnological applications. The amino acid sequence obtained through MALDI-TOF–MS revealed that the purified esterase from Serratia sp. shared significant similarity with the pameloyl-[acyl carrier protein] methyl ester esterase (Serratia marcescens).

Acknowledgements

The financial support from department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Govt. of India to the Department of Biotechnology, Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla (India), is thankfully acknowledged. The Fellowship granted to Mr. Kamal Kumar Bhardwaj (CSIR Fellowship- 09/237(0156)/2016-EMR-I) in the form of SRF from the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research under Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, isalso thankfully acknowledged.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- Ayna C, Kolcuoğlu Y, Öz F, Colak A, Ertunga NS. Purification and characterization of a pH and heat stable esterase from Geobacillus sp. TF17. Turk J Biochem. 2013;38:329–336. doi: 10.5505/tjb.2013.36035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj KK, Saun NK, Gupta R. Immobilization of lipase from Geobacillus sp. and its application in synthesis of methyl salicylate. J Oleo Sci. 2017;66:391–398. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess16153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj KK, Mehta A, Thakur L, Gupta R. Influence of culture conditions on the production of extracellular esterase from Bacillus licheniformis and its characterization. J Oleo Sci. 2020;69:467–477. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess19261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisswanger H. Enzyme assays. Perspect Sci. 2014;1:41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pisc.2014.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boekema KHL, Beselin A, Breuer M, Hauer B, Koster M, Rosenau F, Jaeger K, Tommassen J. Hexadecane and Tween 80 stimulate lipase production in Burkholderis glume by different mechanisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:3838–3844. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00097-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FF, Pinheiro ABP, Gerhardt ECM, Oliveira MAS, Barbosa-Tessmann IP. Production, purification and characterization of a novel serine-esterase from Aspergillus westerdijkiae. J Basic Microbiol. 2018;58:131–143. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201700509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Liang W, Li Y, Li H, Liu X. Identification and immobilization of a novel cold-adapted esterase, and its potential for bioremediation of pyrethroid-contaminated vegetables. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0767-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Mao X, Lu P, Secundo F, Xue C, Sun J. Cloning, expression and characterization of a novel thermostable and alkaline-stable esterase from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia OUC_Est10 catalytically active in organic solvents. Catalysts. 2019;9:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Kumari A, Syal P, Singh Y. Molecular and functional diversity of yeast and fungal lipase: their role in biotechnology and cellular physiology. Prog Lipid Res. 2012;57:40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K, Kataoka M, Ono H, Sakamoto K, Kita S, Shimizu S. Purification and characterization of a novel esterase promising for the production of useful compounds from Microbacterium sp. 7–1W. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;206:221–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotelier T, Renault L, Cousin X, Negre V, Marchot P, Chatonnet A. ESTHER, the database of the α/β-hydrolase fold superfamily of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:145–147. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immanuel G, Esakkiraj P, Palavesam A. Solid state production of esterase using groundnut oil cake by fish intestinal isolate Bacillus circulans. KKU Res J. 2010;15:459–474. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen PH, Monk CR, Morgan HW. A thermophilic, lipolytic Bacillus sp. and continuous assay of its p-nitrophenyl-palmitate esterase activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;120:195–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07030.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaouani A, Neifar M, Hamza A, Chaabouni S, Martinez MJ, Gtar M. Purification and characterization of a highly thermostable esterase from the actinobacterium Geodermatophilus obscurus strain G20. J Basic Microbiol. 2012;52:653–660. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201100428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Patil S, Satpute S. Microbial esterases: an overview. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2013;2:135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar AM, Ranjitha P. Purification and characterization of esterase from marine Vibrio fischeri isolated from squid. Indian J Mar Sci. 2009;39:262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Katwal S, Sharma B, Sharma A, Kanwar SS. Purification, characterization and cytotoxic properties of a bacterial RNase. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;166:665–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R, Majumder MM, Lievonen J, Silvennoinen R, Anttila P, Nupponen NN, Lehmann F, Heckman CA. Prognostic significance of esterase gene expression in multiple myeloma. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:1428–1436. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Liu X. Identification and characterization of a novel thermophilic, organic solvent stable lipase of Bacillus from a hot Spring. Lipids. 2017;52:619–627. doi: 10.1007/s11745-017-4265-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Xie M, Wan P, Chen G, Chen C, Chen D, Yu S, Zeng X, Yi S. Purification, characterization and molecular cloning of a dicaffeoylquinic acid-hydrolyzing esterase from human-derived Lactobacillus fermentum LF-12. Food Funct. 2020;11:3235–3244. doi: 10.1039/D0FO00029A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maester TC, Pereira MR, Malaman AMG, Borges JP, Pereira PAM, Lemos EGM. Exploring metagenomic enzymes: a novel esterase useful for short-chain ester synthesis. Catalysts. 2020;10:1–18. doi: 10.3390/catal10101100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Novototskaya-Vlasova K, Petrovskaya L, Yakimov S, Gilichinsky D. Cloning, purification, and characterization of a cold-adapted esterase produced by Psychrobacter cryohalolentis K5T from Siberian cryopeg. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;82:367–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda T, Gowrishankar BS. Production and applications of esterases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67:160–169. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1840-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Kim J, Kang SG, Woo J, Lee J, Choi H, Kim S. A new esterase showing similarity to putative dienelactone hydrolase from a strict marine bacterium Vibrio sp. GMD509. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;77:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao L, Zhao X, Pan F, Xue Y, Ma Y, Lu JR. Solution behavior and activity of a halophilic esterase under high salt concentration. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoylova YV, Sorokina KN, Alexander VP, Parmon VN. Preparation of stable cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) of Ureibacillus thermosphaericus esterase for application in malathion removal from waste water. Catalysts. 2018;154:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar J, Dutta A, Chowdhury PP, Chakraborty J, Dutta TK. Characterization of a novel family VIII esterase EstM2 from soil metagenome capable of hydrolyzing estrogenic phthalates. Microb Cell Fact. 2020;19:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-01336-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma T, Sharma A, Kanwar SS. Purification and characterization of an extracellular high molecular mass esterase from Bacillus pumilus. J Adv Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Meena KR, Kanwar SS. Molecular characterization and bioinformatics studies of a lipase from Bacillus thermoamylovorans BHK67. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;107:2131–2140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Li Z, Li Q, Shi M, Bao L, Xu D, Li Z. Purification and biochemical characterization of FrsA protein from Vibrio vulnificus as an esterase. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei D, He W, Miao Z, Tu Y, Wang L, Dou W, Wang J. Characterization of esterase genes involving malathion detoxification and establishment of an RNA interference method in Liposcelis bostrychophila. Front Physiol. 2020;11:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin L, Ying YH. Purification and characterization of an extracellular esterase with organic solvent tolerance from a halotolerant isolate Salimicrobium sp. LY19. BMC Biotech. 2013;13:108–112. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, He H, Zhang S, Guo T, Kong J. Characterization of feruloyl esterases produced by the four Lactobacillus species: L. amylovorus, L. acidophilus, L. farciminis and L. fermentum, isolated from ensiled corn stover. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:941–945. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HQ, Liu L, Xu F. The promises and challenges of fusion constructs in protein biochemistry and enzymology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:8273–8281. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7795-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Wub G, Fenga S, Liu Z. Improved thermostability of esterase from Aspergillus fumigatus by site-directed mutagenesis. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2014;64:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen C, Liu H, Chen J, Xia Y, Wu S. Purification, identification and characterization of an esterase with high enantioselectivity to (s)-ethyl indoline-2-carboxylate. Biotechnol Lett. 2019;41:1223–1232. doi: 10.1007/s10529-019-02727-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwane EN, Zyl PJ. Enrichment of maize and triticale bran with recombinant Aspergillus tubingensis ferulic acid esterase. J Food Sci Technol. 2017;54:778–785. doi: 10.1007/s13197-017-2521-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]