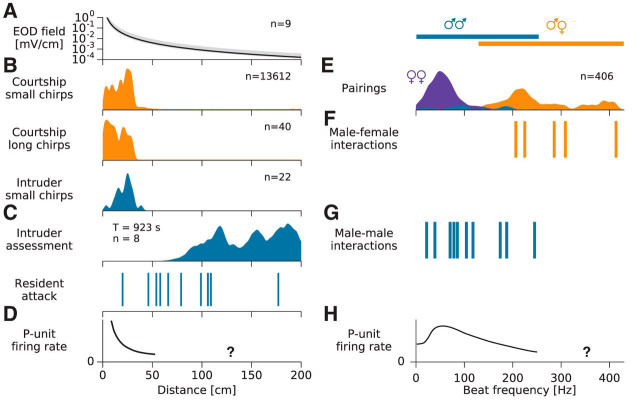

Figure 8.

Statistics of behaviorally relevant natural stimuli. A, Maximum electric field strength as a function of distance from the emitting fish (median with total range). B, Small and long chirps in both courtship and aggression contexts are emitted consistently at distances below 32 cm. C, Intruder assessment and initiation of attacks by residents occur at much larger distances (Movie 3). D, Population-averaged firing rate response of P-unit afferents quickly decays with distance (sketch based on data from Bastian, 1981a, Fig. 6). Responses to stimulus amplitudes corresponding to distances larger than ∼50 cm have not been measured yet (indicated by question mark). E, Distribution of beat frequencies of all A. rostratus appearing simultaneously in the electrode array. Blue, male–male; violet, female–female; orange, male–female (n = 406 pairings). F, Courtship behaviors involving small and long chirps occurred at beat frequencies in the range of 205–415 Hz. G, Male–male interactions involving small chirps emitted by an intruder, intruder assessment, and attacks occurred at beat frequencies below 245 Hz. H, Sketch of the tuning to beat frequencies of population-averaged firing-rate responses of P-unit afferents based on Scheich et al. (1973), Bastian (1981a), Nelson et al. (1997), Benda et al. (2005), and Walz et al. (2014). Almost nothing is known about responses to beat frequencies beyond 300 Hz (indicated by question mark). The data reported by Savard et al. (2011) on stimulus–response coherences and by Sinz et al. (2017) on spike time locking are the only exceptions (see Discussion).