Abstract

Liming is an effective agricultural practice and is broadly used to ameliorate soil acidification in agricultural ecosystems. Our understanding of the impacts of lime application on the soil fungal community is scarce. In this study, we explored the responses of fungal communities to liming at two locations with decreasing soil pH in Oregon in the Pacific Northwest using high-throughput sequencing (Illumina MiSeq). Our results revealed that the location and liming did not significantly affect soil fungal diversity and richness, and the impact of soil depth on fungal diversity varied among locations. In contrast, location and soil depth had a strong effect on the structure and composition of soil fungal communities, whereas the impact of liming was much smaller, and location- and depth-dependent. Interestingly, families Lasiosphaeriaceae, Piskurozymaceae, and Sordariaceae predominated in the surface soil (0–7.5 cm) and were positively correlated with soil OM and aluminum, and negatively correlated with pH. The family Kickxellaceae which predominated in deeper soil (15–22.5 cm), had an opposite response to soil OM. Furthermore, some taxa in Ascomycota, such as Hypocreales, Peziza and Penicillium, were increased by liming at one of the locations (Moro). In conclusion, these findings suggest that fungal community structure and composition rather than fungal diversity responded to location, soil depth and liming. Compared to liming, location and depth had a stronger effect on the soil fungal community, but some specific fungal taxa shifted with lime application.

Keywords: microbial community, wheat, soil acidification, fungal community analysis, soil health

Introduction

Acidic soils are widespread in the world and it is estimated that acidic soils impact over 70% of cultivable and potentially arable land (von Uexküll and Mutert, 1995; Baligar et al., 2001). Soil acidification is a major environmental challenge for crop production in the Inland Pacific Northwest (IPNW) (McFarland and Huggins, 2015; Ghimire et al., 2017), and is a major constraint on plant productivity (Koenig et al., 2013). Continuous use of ammonium-based nitrogen fertilizers and long-term continuous crop growth has caused soil pH to drop below optimum levels for crop production (Schroder et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2019). With soil acidification, pH values below 5.5 increase the solubility and concentration of aluminum (Al3+) and manganese (Mn2+) in soil which can cause phytotoxicity and reduced crop yields (Kidd and Proctor, 2001; Schroder et al., 2011; Schroeder and Pumphrey, 2013; Lewis et al., 2018). In addition, lower pH also reduces water uptake and soil nutrient availability for plants (Kemmitt et al., 2006). To alleviate the harmful effects of low soil pH on crops, lime can be applied to buffer soil acidification, minimize toxic effects of Al3+ and Mn2+, and increase soil fertility and plant ecosystem health (Holland et al., 2018; Lewis et al., 2018; Schroeder et al., 2018).

Soil acidity, represented by low pH and high concentration of aluminum and manganese in soil, affects the activity, structure and composition of the soil microbiome, which consequently influences soil function (Lauber et al., 2009; Klaubauf et al., 2010; Narendrula-Kotha and Nkongolo, 2017). Soil pH is considered to be one of the most important soil health indicators (Kemmitt et al., 2006; Rousk et al., 2009), strongly influences microbial communities (Thompson et al., 2017; Jin and Kirk, 2018) and impacts the metabolic activity of the soil microbiome (Leprince and Quiquampoix, 1996; Kotsyurbenko et al., 2004; Ye et al., 2012). Lime application in acidic soil increases soil pH, especially in the soil surface (Lewis et al., 2018; Yin et al., submitted manuscript). Numerous studies have examined the impacts of lime on soil microbes and revealed that lime application changed soil microbial composition and regulated their activities and functions (Narendrula-Kotha and Nkongolo, 2017; Lewis et al., 2018; Schroeder et al., 2018; Pang et al., 2019). Our recent study found that liming has a small effect on soil bacterial communities and the impacts were especially prominent in the surface soil, compared with location and soil depth (Yin et al., submitted manuscript). In addition, liming has been shown to effectively inhibit microbial pathogen populations and reduce disease incidence (Jones et al., 1975; Gatch and duToit, 2017). However, a majority of these studies focused on the changes of bacterial communities after lime amendments in agricultural soil, while the impact of lime on fungal communities is less understood.

Fungi are the second most abundant group of soil microbiota in density and share microhabitats with bacteria. Fungi play key roles in the decomposition of plant residues and organic materials (Rousk et al., 2009; Žifčáková et al., 2016), and are mycorrhizal associates (Smith and Read, 1997; Marcot, 2017), plant pathogens (Maron et al., 2011) and pathogen antagonists (Heydari and Pessarakli, 2010). Compared to bacteria, fungi can live in soil environments across a wider range of pH, temperature and C:N ratios (Strickland and Rousk, 2010; Fra̧c et al., 2015). Despite the broad habitat preferences of fungi, soil acidification may change the composition of the soil fungal community, and consequently, affect the transformation and availability of nutrients for plants (Kemmitt et al., 2006; Al-Sadi and Kazerooni, 2018; Ning et al., 2020). Previous studies on investigating the effects of liming on the fungal community reported conflicting results. For example, Bothe (2015) and Wan et al. (2019) found that liming changed both bacterial and fungal communities. On the contrary, Pennanen et al. (1998) and Pawlett et al. (2009) revealed that liming reduced bacterial phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) but did not impact fungal PLFAs. To date, the knowledge of soil fungi response to liming is very limited which makes it difficult to understand the roles of liming on fungal communities in acidic soil.

In this study, we established winter wheat plots in two precipitation zones in Oregon, applied four different rates of lime, and conducted Illumina Miseq to explore the response of the soil fungal community to lime amendments. The objectives of this study were to investigate the impacts of liming, location, and soil depth on the soil fungal community over 2 years. We hypothesized that (1) liming will significantly influence the soil fungal community composition and diversity; and (2) location and soil depth will modulate the impacts of liming on soil fungal communities.

Materials and Methods

Study Site and Experimental Design

This study was conducted in two wheat field sites in Oregon within the IPNW, United States which are Columbia Basin Agricultural Research Center (CBARC) in Pendleton (hereafter Pendleton) and the CBARC Sherman Station in Moro (hereafter Moro). Pendleton is in Umatilla County, OR (45.718874, -118.624236) and Moro is in Sherman County, OR (45.483149, -120.725561). The dominant soil type at both locations was a Walla Walla silt loam: coarse-silty, mixed, and mesic Typic Haploxerolls (Web Soil Survey, 2013) and soil pH was below 5.2 in the top 15 cm. The annual precipitation at Pendleton (442 mm) was higher than at Moro (282 mm).

Total field size was 58.5 m wide by 60.9 m long and the experimental plot size within the field was 7.3 m wide by 15.2 m long. Each study site had 16 plots (four treatments × four replicates) which were randomly arranged. Thus, a total of 32 plots were established in two study sites. Winter wheat cv. “Stephens” was seeded with a no-till plot drill 39 and 86 kg/ha urea was added at planting at the Moro and Pendleton locations, respectively. Before planting, four different rates (0, 673, 1,345, and 2,690 kg ha–1) of ultrafine liquid calcium carbonate (CaCO3, NuCal, Columbia River Carbonates, Vancouver, WA) were applied to surface soil using a custom sprayer outfitted with a Boom Buster (Millen, Georgia) spray nozzle designed to spray a 7.6-m swath in fall, 2016. Within 7 days of the application the plots were subject to light vertical tillage with a Turbo Max (Great Plains Ag. Inc., Salina KS) implement at 0° at both locations. Minimal tillage was conducted at both locations. All plots were managed using an appropriate fertility program including nitrogen and other nutrients based on soil test reports. Weed management and pest control were typical for production of winter wheat in this region.

Soil Sampling and Chemical Analyses

Soil samples were collected from the two study sites in April 2017 and March 2018, respectively. Soil samples were taken down to a depth of 22.5 cm using a 2.5 cm diameter hand soil probe. The soil core was removed from the probe and separated based on depth: 0–7.5 cm, 7.5–15 cm, and 15–22.5 cm. Each lime treatment consisted of a composite of four soil cores. A total of 48 composite samples per location each year were divided into two portions and stored at −20°C for further analysis.

One portion of the soil samples was sent to a commercial soil lab (Best-Test Analytical Services, Moses Lake, WA) for soil physiochemical characteristics analysis as described by Schroeder et al. (2018). Analyses conducted in this study included organic matter (OM), pH, exchangeable bases (Ca, Mg, and Na), DTPA extractable aluminum (DTPA-Al), KCl extractable aluminum (KCl-Al), Cl, SO4.S, B, Zn, Mn, Cu, Fe, N, P, K, and the cation exchange capacity (CEC). Briefly, soil organic matter (OM) was determined using Walkley-Black titration. Exchangeable bases (Ca, Mg, and Na) and Al were extracted with KCl and measured by mass spectrophotometry. The concentrations of Al, SO4.S, B, Zn, Fe, Cu, and Mn were extracted with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) and measured by mass spectrophotometry. The quantities of K and P were determined using the Olson method, nitrate nitrogen was measured using the chromotrophic acid method, and the cation exchange capacity (CEC) was estimated using the ammonium replacement method.

DNA Extraction and Illumina Sequencing

Microbial DNA was extracted from 0.25 g of the second portion of soil samples (stored for 2 weeks at −20°C) using a MoBio PowerSoil kit (MoBio/Qiagen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturers’ instruction. Homogenization of soil samples was performed with a FastPrep bead beater (MP Biomedical, Santa Ana, CA) using the “soil” program. The DNA was quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and sent to the University of Minnesota Genomics Center (UMGC) for amplification and sequencing. PCR amplification used a dual-indexing approach, as described previously (Gohl et al., 2016). Briefly, the fungal ITS1 region was amplified in the first round of PCR using primers ITS1∗_Nextera (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGT ATAAGAGACAGCTTGTCATTTAGAGGAAG∗TAA-3′) and ITS2 (5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACA GGCTGCGTTCTTCATCGA∗TGC-3′). The first PCR consisted of an initial denaturing at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The products from the first PCR were diluted 1:100, and 5 μl was included in a second PCR using forward indexing primer (5′-AATGATACG GCGACCACCGAGATCTACAC[i5]TCGTCGGCAGCGTC-3′) and reverse indexing primer (5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCA TACGAGAT[i7]GTCTCGTGGGCTCGG-3′) (i5 and i7 refer to the index sequence codes used by Illumina. The flow cell adapters are in bold). The second PCR consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 10 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The products were pooled, size selected, and spiked with 20% PhiX prior to sequencing with an Illumina MiSeq 600 cycle version 3 kit. qPCR was performed to quantify copy numbers of bacterial community from each sample with 16S rRNA primers Meta_V4_515F (5′-TCGTCG GCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGTGCCAGCMGC CGCGGTAA-3′) and Meta_V4_806R (5′- GTCTCGTGGG CTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGGACTACHVGGGTW TCTAAT-3′) (16S-specific portion in bold) and ITS primers ITS1-F (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGAC AGCTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAG∗TAA-3′) and ITS2 (5′-GT CTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGCTGCG TTCTTCATCGA∗TGC-3′) (ITS-specific portion in bold). qPCR conditions for 16S RNA and ITS consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 55°C for 15 s and extension at 72°C for 60 s, with the final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The raw sequence data was deposited in OSFHOME1.

Sequence Processing

The sequence processing was conducted using USEARCH (version 11; 42) to denoise sequences and define operational taxonomic units (OTUs). Briefly, primer and barcode sequences were removed along with 50 and 75 base pairs from the 3′ end of forward and reverse reads, respectively. Reads were paired with 15 maximum differences and an 80% identity threshold, followed by the removal of conserved regions at the forward and reverse ends of reads (81 and 68 base pairs, respectively). To generate high-quality reads for denoising, reads were filtered with a maximum expected error rate of 1, singletons were removed, and sequences were denoised using the “unoise3” algorithm. Processed reads were then mapped to OTU representatives to generate an OTU abundance table. Taxonomy was assigned to OTUs using the SINTAX algorithm with an 80% confidence threshold to the SINTAX formatted UNITE database (version 7). OTUs identified as non-fungal were discarded and OTU tables were rarefied to 16,000 sequences per sample for all analyses unless otherwise noted. Material-free extraction controls indicated minimal cross-contamination of fungal sequences in OTU tables prior to rarefaction, thus no removal of contaminant OTUs was necessary.

Statistical Analyses

The ratio of fungi and bacteria was calculated using copy number of bacterial and fungal community from each sample and compared among treatments by Kruskal-Wallis test. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was performed to visualize fungal community similarity among soil samples based on Bray-Curtis distances using the “metaMDS” function of the vegan package (version 2.4.1) in R. Soil chemical characteristics were fitted to the NMDS ordination with the “envfit” function of vegan. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was conducted using the “Adonis” function of the vegan package (nperm = 999). Fungal richness and Shannon diversity (H’) were calculated and compared among treatments by Kruskal-Wallis test. The abundance of fungal families (>0.1% of sequences) was compared among treatments by Kruskal-Wallis test. DESeq2 was used to identify OTUs that differed after lime application within soil depth and location using unrarefied OTU tables filtered to remove low abundance taxa (<10 total counts) and those found in fewer than 3 samples. OTUs were considered as differentially abundant if they had a base mean >50, FDR adjusted p-values of <0.1, and estimated log2-fold change >1. Spearman correlations were used to evaluate relationships between fungal families and soil chemical characteristics using the “corr.test” function in the Hmisc package in R.

Results

Soil Fungal Community

After sequence data processing, 5,460,052 sequences were obtained with a minimum of 16,000 sequences per sample. These sequences were mapped to 4,824 OTUs prior to rarefaction. After rarefaction, the most dominant phylum in soil fungal community was Ascomycota (37.3 ± 0.47%, mean ± SE), followed by Mortierellomycota (13.9 ± 0.49%), and Basidiomycota (13.1 ± 0.49%). Ten other phyla, Chytridiomycota, Calcarisporiellomycota, Kickxellomycota, Rozellomycota, Olpidiomycota, Basidiobolomycota, Glomeromycota, Zoopagomycota, Monoblepharomycota, and Mucoromycota were also present in the test soil but at a lower frequency (less than 2.0%). The four most abundant families comprised over 26% of taxa in all samples, which were Mortierellaceae (13.8 ± 0.49%), Aspergillaceae (5.6 ± 0.27%), Piskurozymaceae (4.4 ± 0.19%), and Herpotrichiellaceae (2.7 ± 0.15%).

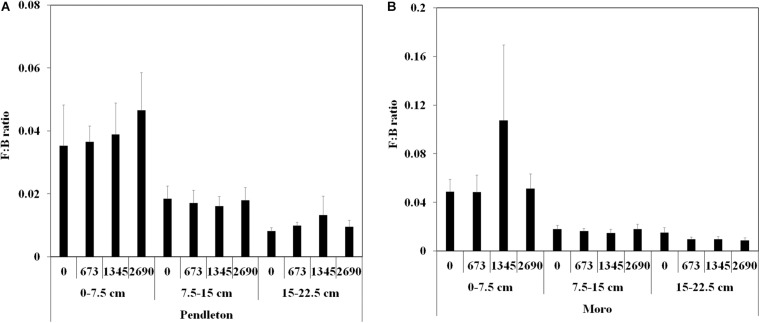

Fungal to bacterial abundance ratios (F:B) were higher in the surface soil (0–7.5 cm) than in the deeper soil (7.5–15 and 15–22.5 cm) at both locations (p ≤ 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test) (Figure 1). But no significant difference of F:B ratio was observed between lime and no lime applications in each soil depth at two locations.

FIGURE 1.

Fungal: bacterial abundance ratios from soil at two wheat locations. (A) Pendleton. (B) Moro. F:B ratio: fungal: bacterial abundance ratio; Soil depth: 0–7.5 cm, 7.5–15 cm, and 15–22.5 cm; rate of lime application: 0, 673, 1,345, and 2,690 kg ha–1; The values are means (n = 8) ± SE (p ≤ 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test).

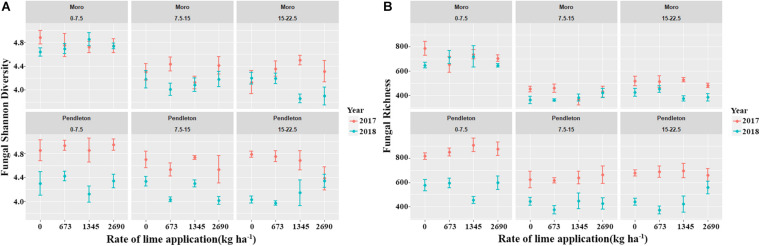

Fungal diversity and richness varied between two sampling times (year 2017 and 2018) (p ≤ 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test) (Figure 2). However, lime applications did not significantly impact fungal diversity and richness, compared with the no lime control treatment. In addition, fungal diversity and richness from the surface soil were significantly higher than those of the deeper soils at Moro, and only fungal richness from the surface soil was higher than that of the deeper soil at Pendleton (p ≤ 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test), but no difference of fungal diversity was observed. These results indicate that liming, location, and soil depth had marginal and inconsistent impacts on fungal diversity, while time after liming had greater influence on fungal diversity.

FIGURE 2.

Fungal diversity and richness indices among locations, soil depth, years, and lime applications. (A) Fungal Shannon diversity. (B) Fungal richness (p ≤ 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test).

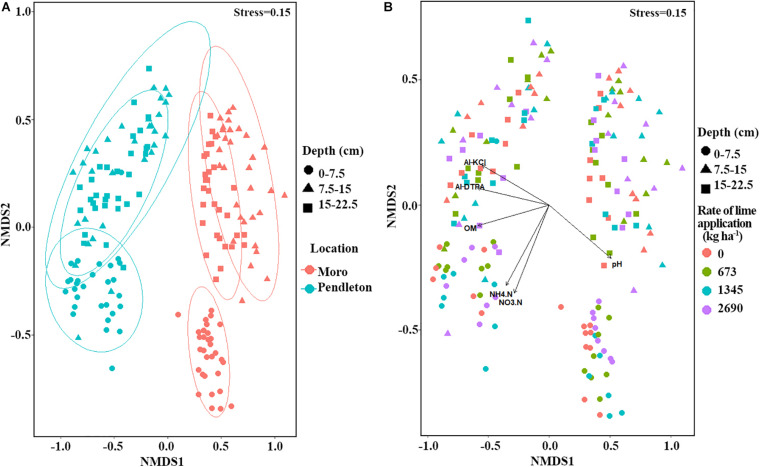

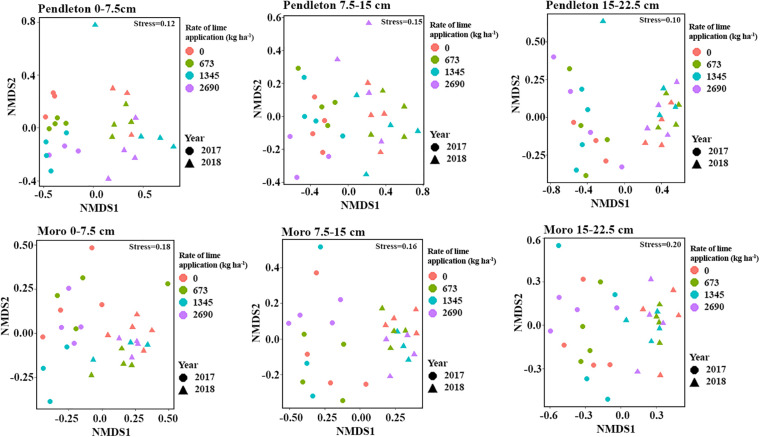

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) and PERMANOVA analyses of fungal community composition revealed significant location (PERMANOVA r2 = 0.19, p = 0.001) and soil depth (PERMANOVA r2 = 0.15, p = 0.001) effects (Figure 3A). A small but significant effect of liming (PERMANOVA r2 = 0.02, p = 0.015) on fungal community composition was observed (Figure 3B). Additionally, fungal community dissimilarities were significantly correlated with soil chemical parameters, including organic matter (OM), DTPA-Al, KCl-Al, pH, and nitrogen (NH4.N and NO3.N) (Figure 3B). Further, fungal communities from different locations and soil depths were analyzed independently using NMDS. The results showed that time after lime treatment (year) influenced fungal composition (PERMANOVA, p = 0.001). The impacts of liming on fungal community composition were only observed in the surface soil at Moro (PERMANOVA r2 = 0.12, p = 0.008), but not in the surface soil at Pendleton or in deeper soils at either location (p > 0.27) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) of fungal community from all samples (Bray-Curtis distances). (A) NMDS of fungal community within location and soil depth. (B) NMDS of fungal community within soil depth and lime application. Symbols represent soil depth and colors represent location or rate of lime application. Vectors represent significant associations of soil chemical factors along with axes (vegan, p ≤ 0.05). Al-DTPA, DTPA extractable aluminum; Al-KCl, KCl extractable aluminum.

FIGURE 4.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) of fungal community within locations and soil depth (Bray-Curtis distances). Symbols represent sample time after liming (year), and colors represent rate of lime application (kg ha–1).

Effect of Location and Soil Depth on Fungal Taxa

Differences in the relative abundance of fungal families by location and soil depth were observed in soil samples without liming (p ≤ 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test). Eighteen and 14 fungal families were significantly affected by location and soil depth, respectively, where some families were more abundant in the surface soil (0–7.5 cm) (e.g., Coniochaetaceae, Dothioraceae, Lasiosphaeriaceae, Piskurozymaceae, and Sordariaceae), some in deeper soil (15–22.5 cm) (e.g., Calcarisporiellaceae, Geminibasidiaceae, Kickxellaceae, and Mortierellaceae), and some families (Aspergillaceae, Hypocreaceae, and Myxotrichaceae) in the middle layer (7.5–15 cm) (Table 1). Moreover, nine families varied significantly with both location and soil depth.

TABLE 1.

The relative abundance (±standard error) of fungal families significantly impacted by location and soil depth without liming.

| Family (relative abundance%) | Pendleton (cm) | Moro (cm) | p-valuea (location) | p-valuea (soil depth) | ||||

| 0–7.5 | 7.5–15 | 15–22.5 | 0–7.5 | 7.5–15 | 15–22.5 | |||

| Aspergillaceae | 1.960.20 | 4.780.52 | 4.080.88 | 5.740.84 | 11.111.11 | 5.810.93 | 9.11E-05 | 1.53E-02 |

| Calcarisporiellaceae | 0.020.01 | 1.710.31 | 3.491.29 | 0.000.00 | 0.080.05 | 0.230.12 | 2.39E-04 | 2.24E-04 |

| Cantharellales_fam_Incertae_sedis | 0.010.01 | 0.000.00 | 0.050.03 | 0.150.07 | 6.573.71 | 3.723.29 | 4.87E-05 | >0.05 |

| Ceratobasidiaceae | 0.300.15 | 0.340.10 | 0.720.28 | 0.080.04 | 0.160.08 | 0.120.10 | 7.21E-04 | >0.05 |

| Chaetomiaceae | 0.190.07 | 0.230.12 | 0.230.07 | 0.790.16 | 0.720.17 | 0.500.28 | 1.39E-03 | >0.05 |

| Clavicipitaceae | 0.140.09 | 0.590.19 | 0.570.20 | 0.050.01 | 0.620.15 | 0.590.27 | >0.05 | 9.36E-06 |

| Coniochaetaceae | 2.080.61 | 0.280.05 | 0.440.15 | 1.920.57 | 0.420.13 | 0.340.04 | >0.05 | 4.43E-06 |

| Cystofilobasidiaceae | 0.410.10 | 0.250.17 | 0.250.13 | 0.000.00 | 0.010.00 | 0.000.00 | 3.53E-08 | >0.05 |

| Dothioraceae | 0.020.01 | 0.000.00 | 0.010.01 | 0.810.16 | 0.240.08 | 0.490.06 | 1.60E-07 | 3.97E-02 |

| Geminibasidiaceae | 0.020.01 | 0.210.04 | 0.650.16 | 0.080.02 | 1.120.28 | 2.200.57 | 6.11E-03 | 1.20E-06 |

| Herpotrichiellaceae | 1.180.15 | 1.390.19 | 1.980.50 | 4.900.73 | 3.120.65 | 4.520.77 | 1.77E-06 | >0.05 |

| Hypocreaceae | 0.620.37 | 1.800.38 | 0.760.15 | 0.130.03 | 0.590.18 | 0.390.18 | 6.16E-04 | 2.33E-03 |

| Kickxellaceae | 0.010.01 | 0.140.07 | 1.941.14 | 0.050.03 | 0.460.19 | 0.570.24 | >0.05 | 7.07E-04 |

| Lasiosphaeriaceae | 2.510.46 | 0.740.32 | 0.550.25 | 0.740.25 | 0.340.14 | 0.180.11 | 1.80E-02 | 1.67E-03 |

| Mortierellaceae | 7.091.29 | 15.851.34 | 16.451.84 | 8.781.15 | 14.042.27 | 16.372.35 | >0.05 | 6.49E-05 |

| Myxotrichaceae | 0.020.01 | 0.150.06 | 0.050.02 | 0.080.03 | 0.200.08 | 0.090.05 | >0.05 | 7.56E-03 |

| Orbiliaceae | 0.010.00 | 0.010.00 | 0.080.03 | 0.200.02 | 0.050.02 | 0.230.09 | 6.77E-05 | 5.96E-03 |

| Piskurozymaceae | 5.630.95 | 7.891.21 | 4.520.61 | 3.690.27 | 3.550.52 | 1.640.31 | 9.10E-05 | 7.18E-03 |

| Sordariaceae | 3.861.10 | 0.820.22 | 0.760.42 | 0.040.02 | 0.050.03 | 0.040.03 | 3.65E-07 | >0.05 |

| Teratosphaeriaceae | 0.000.00 | 0.000.00 | 0.000.00 | 0.570.12 | 0.360.24 | 0.480.14 | 7.34E-09 | >0.05 |

| Xylariaceae | 0.010.00 | 0.000.00 | 0.010.01 | 0.460.25 | 0.220.15 | 0.020.01 | 8.05E-05 | >0.05 |

| Chaetosphaeriaceae | 0.590.18 | 0.780.07 | 0.760.08 | 0.080.02 | 0.660.28 | 0.960.61 | 1.33E-03 | 3.04E-02 |

| Helotiaceae | 0.030.01 | 0.100.05 | 0.550.47 | 0.130.05 | 0.230.08 | 0.290.09 | 1.15E-02 | >0.05 |

aKruskal-Wallis test.

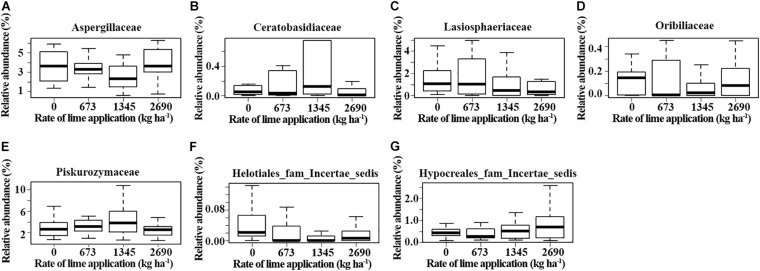

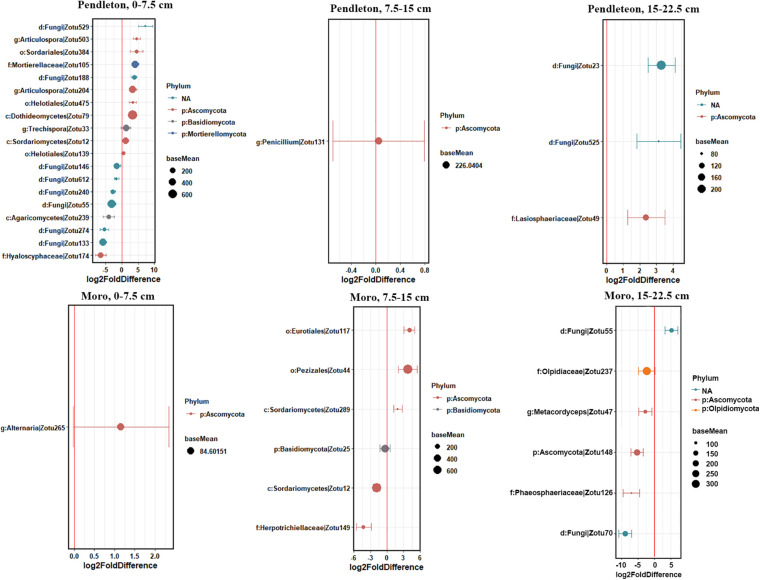

Effect of Lime Applications on Fungal Taxa

Some fungal families varied in relative abundance with lime application in different soil depths at each location (p ≤ 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test) (Figure 5). These families included Chaetosphaeriaceae, Helotiaceae and Lasiophaeriaceae at Pendleton, and Aspergillaceae, Lasiophaeriaceae, Pezizaceae and Thelebolaceae at Moro in the surface soil. Notably, the abundance of Helotiaceae and Pezizaceae increased with rate of lime application, while Lasiophaeriaceae showed an opposite trend. The abundance of Dothioraceae and Helontialea_fam_Incertae_sedis at Pendleton and Entolomataceae and Helontialea_fam_Incertae_sedis at Moro varied with lime application in middle layer (7.5–15 cm). Families Herpotrichiellaceae and Orbiliaceae varied with lime application in deeper soil (15–22.5 cm) at Pendleton. No family in deeper soil at Moro was affected by liming. Furthermore, DESeq2 analysis identified 53 (0–7.5 cm soil), 5 (7.5–15 cm soil), and 6 (15–22.5 cm soil) OTUs at Pendleton, and 12 (0–7.5 cm soil), 22 (7.5–15 cm soil), and 6 (15–22.5 cm soil) OTUs at Moro that differed in abundance after liming application (base mean > 50) (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure 1). A total of 32 OTUs increased and 32 OTUs decreased by liming at Pendleton, and 20 OTUs increased and 20 OTUs decreased by liming at Moro, respectively. However, most OTUs impacted by liming were soil depth- or location-dependent, where OTU 148 had a consistent negatively response to liming in both 7.5–15 cm and 15–22.5 cm soil at Moro, and OTU 32 had a consistent positive response to liming in surface soil at Pendleton and middle layer soil at Moro, while OTU 49 (Lasiosphaeriaceae) exhibited an opposite response to liming in 7.5–15 cm and 15–22.5 cm soil at Pendleton (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure 1). Interestingly, several fungal taxa among these OTUs known for their roles as pathogens, such as Herpotrichiellaceae, Alternaria, and Sordariomycetes, were found. On the other hand, a few taxa were reported to have members with biocontrol activities, such as Hypocreales and Mortierella. Moreover, a few genera, including Trichoderma and OTU 127 (order Hypocreales), Peziza (order Pezizales), and Penicillium (order Eurotiales), in Ascomycota were increased by liming at Moro location. Taken together, these results indicate that the impacts of liming on soil fungal taxa were inconsistent and location- and soil depth- dependent.

FIGURE 5.

Fungal families that were impacted by lime application at different soil depths. (A–D) 0-7.5 cm soil, (E) 7-15 cm soil, and (F–G) 15-22.5 cm soil. Box: interquartile range. Mean: the heavy line in the box (p ≤ 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test).

FIGURE 6.

Fungal OTUs that were differentially abundant among lime application within soil depth at each location. Soil depth: 0–7.5 cm, 7.5–15 cm, and 15–22.5 cm. Values on the X-axis represent the log2-fold difference in sequence abundance among lime amendments as estimated by DESeq2. Points to the right of red vertical line are more abundant in lime amendments, whereas those to the left of red vertical line are less abundant in lime amendments. Dots indicate OTUs, where the size of the dot is scaled by its mean abundance among all samples (baseMean > 50) and its color represents the phylum to which that OTU belongs. The nearest taxonomy assignment is presented at left. Only OTUs with a mean abundance >10 and normalized counts >5 and present in at least 3 samples are presented.

Relationships of Fungal Communities With Soil Chemical Properties

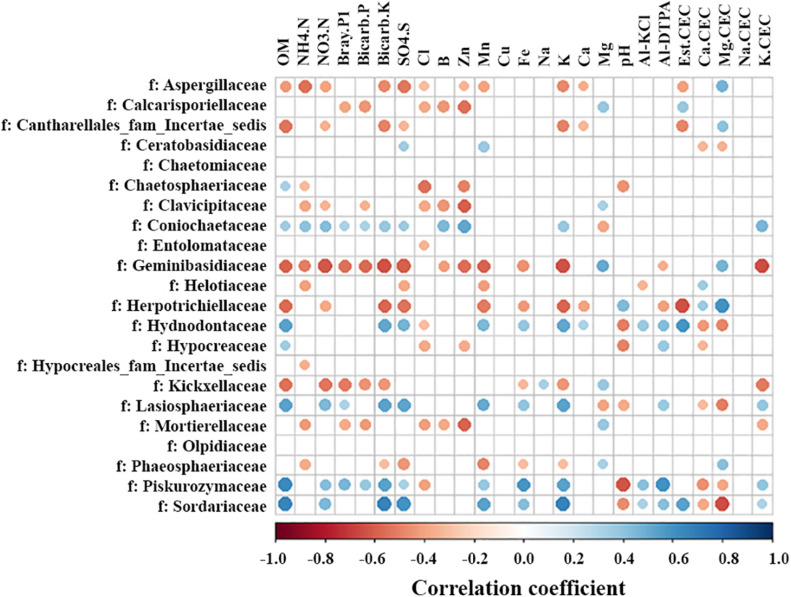

Lime application changed soil chemical properties, including increasing pH and the levels of Ca2+ and calcium cation exchange capacity (Ca. CEC) (Yin et al., submitted manuscript, Supplementary Figures 2, 3). Additionally, a strong negative correlation was observed between the organic matter (OM) and soil depth (Supplementary Figure 3). The impacts of soil chemical properties on fungal families were analyzed. Most interestingly, the response of some fungal families to soil OM and pH was opposite (Figure 7). For example, fungal families were positively correlated with soil OM and negatively with pH, including Chaetosphaeriaceae, Hydnodontaceae, Hypocreaceae, Lasiosphaeriaceae, Piskurozymaceae, and Sordariaceae. Whereas Herpotrichiellaceae was negatively correlated with OM and positively correlated with pH. Compared with pH, six of seven families had opposite correlations with Al-KCl or Al-DTPA or both (Figure 7). Further, the correlations between soil chemical properties and fungal families from different soil depths were analyzed independently (Supplementary Figure 4). Similar trends were found although the opposite response of a few fungal families to OM and pH was observed only in the surface (e.g., Lasiosphaeriaceae) or deeper soil (e.g., Calcarisporiellaceae and Hydnodontaceae). In addition, other soil characteristics, such as nitrogen (NH4. N and NO3.N), P, K, and cation exchange capacity, had positive or negative correlations with fungal families (Figure 7). These results suggest that soil characteristics are important drivers of the fungal community.

FIGURE 7.

Heatmap of significant spearman correlations between fungal family abundance and soil chemical characteristics. OM, organic matter; Al-KCl, KCl extractable aluminum; Al-DTPA, DTPA extractable aluminum; CEC, cation exchange capacity and the element listed before CEC (i.e., Ca.CEC) represents the proportion of the CEC comprised of that specific cation. Significance was examined using R statistical software (p ≤ 0.05 and absolute r-value cut off 0.3).

Discussion

Few studies have addressed the impact of lime application in agricultural soil on the soil fungal community. We investigated the changes in the soil fungal community after liming at two locations with decreasing soil pH in the IPNW using high-throughput sequencing. Contrary to bacterial communities (Yin et al., submitted manuscript), location and liming did not significantly influence fungal diversity and richness in soil, while the impacts of soil depth on fungal diversity were location-dependent. These results were consistent with the work by Narendrula-Kotha and Nkongolo (2017) who showed that soil liming had limited effects on fungal diversity. They were also in agreement with work by Al-Sadi and Kazerooni (2018) who reported that no significant differences of Chao richness and Shannon diversity existed in root samples taken from limed soils. However, this is not always the case for fungal diversity. Lin et al. (2018) showed that lime or pig manure altered fungal community diversity due to soil pH increase in Ultisols. Generally, fungi can live in a wider range of pH than bacteria (Strickland and Rousk, 2010). In our study sites, liming ameliorated soil acidification in the surface soil (0–7.5 cm) and soil pH slightly increased with soil depth in both locations (Yin et al., submitted manuscript, Supplementary Figure 2). Increasing pH by liming or soil depth may benefit some fungi which are favored by relatively higher pH conditions (Rousk et al., 2010). On the other hand, increased pH may suppress the growth of other fungi which are well-adapted to acidic soil (Dix and Webster, 1995). Consequently, fungal diversity appeared to be unaffected by location and liming.

Contrary to fungal diversity, fungal community composition was significantly influenced by location and soil depth. Notably, stratification of fungal families was observed, where families such as, Coniochaetaceae, Dothioraceae, Lasiosphaeriaceae, Piskurozymaceae, and Sordariaceae tended to predominate in surface soil, whereas families Calcarisporiellaceae, Clavicipitaceae, Geminibasidiaceae, Kickxellaceae, and Mortierellaceae predominated in deeper soil. Moreover, the surface soil enriched families, Lasiosphaeriaceae, Piskurozymaceae, and Sordariaceae, were positively correlated with soil OM and aluminum, and negatively with pH, whereas deeper soil enriched family Kickxellaceae showed an opposite correlation with soil OM. OM was higher in the surface soil and decreased with soil depth in our study sites. Plant residue and litter layer may result in increased OM in the surface soil, while plant residue is expected to be reduced with depth, which is likely to be reflected by less OM in deeper soil. Similar to OM, soluble aluminum was negatively correlated with soil depth, but pH showed an opposite trend with lower pH in the surface and higher pH in deeper soil. These results suggested that variation in fungal families across soil depths may track stratification in OM, pH, and aluminum in soil. Further, earlier studies also supported these findings. For example, fungal community composition was found to be distinct at different soil depths (Ko et al., 2017). Li et al. (2017) revealed that the relative abundances of bacteria and fungi significantly decreased at 0–40 cm depths. Similarly, fungal community varied with the soil depths (Prober et al., 2015; Schlatter et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2019). In addition, Schlatter et al. (2018) found that family Lasiosphaeriaceae was more abundant at soil surface, while Clavicipitaceae were in deeper soil (10–25 cm). Taken together, stratification of OM, aluminum, and pH across soil depths may generate distinct fungal communities.

Similar to the small impacts of liming on bacterial community observed in our companion work (Yin et al., submitted manuscript), we found a subtle effect of liming on fungal community composition. However, liming influenced the abundance of 11 fungal families in different soil depths at two locations and seven families had strong correlations with soil pH (Figures 5, 7). Most notably, the abundance of family Lasiosphaeriaceae (phylum Ascomycota) decreased with greater lime concentration in the surface soil and had negative correlations with soil pH. Liming significantly increased soil pH in the surface soil at two locations, suggesting that liming decreased the abundance of Lasiosphaeriaceae through increasing soil pH. Liming also decreased aluminum concentration in the surface soil, and significantly increased soil calcium concentration (Yin et al., submitted manuscript) which may reduce the solubility of OM (Balaria et al., 2014). The abundance of Lasiosphaeriaceae was positively correlated with soil OM and aluminum (Figure 7), which could explain the abundance of Lasiosphaeriaceae which decreased with greater lime concentration in the surface soil. In addition, some Ascomycetes are important sources of extracellular enzymes (Moorhead et al., 2012) and liming may decrease the activities of some extracellular enzymes (Cenini et al., 2016; Sridhar et al., 2018), which may be the other reason for less abundant Lasiosphaeriaceae in the surface soil. Similar trends were also observed in the abundance of family Chaetospheriaceae in the surface soil at Pendleton. In contrast, the abundance of Helotiaceae at Pendleton and Pezizaceae at Moro in the surface increased with the rate of lime application. Interestingly, Helotiaceae was positively correlated with soil Ca, but negatively correlated with soil Al, indicating the increase of Helotiaceae with the rate of lime application through increasing soil Ca and decreasing Al after liming. In addition, Helotiaceae was negatively correlated with soil NH4. Helotiaceae is a small group of fungicolous, lichenicolous, and discomycetes members (Zhuang, 2000) and was reported to be positively correlated with soil carbon accumulation (Zhang et al., 2017). Nagati et al. (2019) found that higher abundance of Helotiaceae was associated with the lower N nutrition of balsam fir near ericaceous shrubs. Moreover, previous studies reported that soil C:N ratio significantly increased with liming and the effect of liming on soil fungal community was closely tied to the way liming affected the C:N ratio (Melvin et al., 2013; Suz et al., 2014). It is suggested that the abundance of Helotiaceae may be related to soil nutrient is C:N ratio. Tedersoo et al. (2006) revealed that some pezizalean species were distributed in the forests with a high pH, which was consistent with our findings. In addition, it was unexpected that the abundance of ascomycete family Nectriaceae was very low (<0.1%) in our soil. Nectriaceae includes numerous important plant pathogens, such as Fusarium spp. soilborne pathogens which are usually very common and associated with plant debris and roots in agricultural soil (Silvestro et al., 2013; Karim et al., 2016). However, the impacts of liming on fungal community were observed in short term (2 years) after lime applications. A few previous studies reported that impact zones with increased pH and the changes of soil chemistry reached to depths of 50, 55, and 60 cm in over 10 years after liming (Tang et al., 2003; Caires et al., 2008; Santos et al., 2018). The microbial properties under longer timescale liming need to be further addressed. In summary, location and soil depth significantly influenced fungal community composition, while lime had a smaller impact. A small number of fungal families varied in relative abundance after liming and liming influenced some fungal family abundance through increasing soil pH.

The ratio of fungal and bacterial abundance (F:B) was considered to have important ecological significance in soil ecology and affected by environmental changes (Strickland and Rousk, 2010; Wang et al., 2019). We found that the ratios of F:B were higher on the surface soil than that of deeper soil at both locations. It is probable that fungi are less affected by soil pH than bacteria (Rousk et al., 2010), thus dominate in surface soil resulting in a higher ratio of F:B than the deeper soil. Another possibility is that there is more plant residue in the surface soil than the deeper soil. Although both bacteria and fungi are decomposers in agro-ecosytems, the roles they play are different. Compared to bacteria, soil fungi mainly decompose recalcitrant organic materials, such as lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, whereas bacteria degrade labile fractions (Strickland and Rousk, 2010; Chen et al., 2014). Thus, the surface soil may enrich more fungi than the deeper soil for plant residue decomposition. Finally, the oxygen concentration in the deeper soil is much lower than those in the surface soil which may also change the microbial distribution.

Findings from this study revealed that the most dominant fungal phylum was Ascomycota, accounting for >35% of fungi in examined soil. Ascomycota is the dominant phylum of fungi in agricultural ecosystems and its high presence in our soil is not unexpected. Ascomycota play significant roles in nutrients and carbon cycling and induce the uptake of mineral nutrients for plants (Semenova et al., 2015; Francioli et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2018). The second and third most dominant phyla were Mortierellomycota and Basidiomycota, accounting for similar abundance. Mortierella is the largest genus in Mortierellomycota and known as a ubiquitous saprobe (Buée et al., 2009). Basidiomycota, rather than Ascomycota, was dominant in terrestrial ecosystems such as forests but was much lower in agricultural soils (Francioli et al., 2016) which supported our results. Most interestingly, a few genera, including Trichoderma and OTU 127 (order Hypocreales), Peziza (order Pezizales) and Penicillium (order Eurotiales), in Ascomycota were increased by liming at the Moro location. These results were consistent with the works by Narendrula-Kotha and Nkongolo (2017) and Al-Sadi and Kazerooni (2018) who found that Penicillium was more abundant in limed soil than a non-limed site. They were partially in accord with (Ye et al., 2020) who revealed that liming significantly enhanced the relative abundance of the order Hypocreales but had no effect on the relative abundance of Pezizales. Similarly, Pezizales are abundant in forest soil and increased with liming (Kjøller and Clemmensen, 2009; Tedersoo et al., 2014; Ge et al., 2017). Earlier studies showed that some fungi, such as Hypocreales and Peziza, grow well in neutral to slightly alkaline conditions (Yamanaka, 2003; Rousk et al., 2010). Thus, one possible explanation is that increased pH by liming in our study sites promoted the growth of Hypocreales and Peziza and increased their abundance. Some genera of Hypocreales were considered as sources of biocontrol fungi for plant diseases (Bastakoti et al., 2017; Kepler et al., 2017) and Penicillium was reported to interfere with the growth of some fungal pathogens (Yuan et al., 2017). Similarly, genus Mortierella from Mortierellomycota was slightly increased by liming at Moro. Mortierella was reported to be beneficial for plant growth and soil health by releasing P or degrading relative abundances of the toxic compounds and producing antibiotics to inhibit phytopathogens (Tagawa et al., 2010; Osorio and Habte, 2015; Li et al., 2018). A recent study found that the enrichment of Mortierella species increased crop yield (Ning et al., 2020). Therefore, the increased abundance of these taxa in limed soil may contribute to pathogen suppression, promote crop growth, thus indirectly increase crop yields. Further work is needed to verify function of Mortierella in this system. This phenomenon was only observed at Moro, indicating a location dependency.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings revealed minor impacts of liming on soil fungal community composition, similar to small effects on bacterial community (Yin et al., submitted manuscript). Location and soil depth had a strong effect on soil fungal community composition. However, the location and liming did not significantly influence soil fungal diversity and richness. Some fungal taxa, including species associated with plant benefits, varied after lime application which may improve plant growth and increase crop yields.

Data Availability Statement

The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA678975.

Author Contributions

CY: analysis, writing, and bioinformatics. DS: bioinformatics. DK: plot and data management. TP: project conception, direction, and personnel management. CH: project conception, direction, funding, personnel management, and writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Columbia River Carbonates for donating ultrafine liquid lime. We thank Stephen Machado, Paul Carter, Steve Van Vleet, Tim Murray, Kurtis Schroeder, Judit Barroso, and Don Wysocki for their involvement in the Commission-funded objectives. We thank Cuilin Gao for soil DNA extraction.

Funding. This study was funded by the Oregon Wheat Commission, Washington Grain Commission, and USDA-ARS.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.576763/full#supplementary-material

Venn diagram of OTUs influenced by liming treatments among soil depths. (A) Pendleton, (B) Moro.

Soil pH changes after lime amendments at two wheat locations. Soil depth: 0–7.5 cm, 7.5–15 cm, and 15–22.5 cm. The values are means (n = 32) ± SE. Different letters represent significant differences (p ≤ 0.05, Tukey test).

Heatmap of significant Spearman correlations between soil chemical characteristics and soil depth and location. OM, organic matter; Al-DTPA, DTPA extractable aluminum; Al-KCl, KCl extractable aluminum; CEC, cation exchange capacity and the element listed before CEC (i.e., Ca.CEC) represents the proportion of the CEC comprised of that specific cation. Significance was examined using R statistical software (p ≤ 0.05 and absolute r value cut off 0.3).

Heatmap of significant Spearman correlations between fungal family abundance and soil chemical characteristics at different soil depths. OM, organic matter; Al-KCl, KCl extractable aluminum; Al-DTPA, DTPA extractable aluminum; CEC, cation exchange capacity and the element listed before CEC (i.e., Ca.CEC) represents the proportion of the CEC comprised of that specific cation. Significance was determined using R statistical software (p ≤0.05 and absolute r-value cut off 0.3).

References

- Al-Sadi A. M., Kazerooni E. A. (2018). Illumina-MiSeq analysis of fungi in acid lime roots reveals dominance of Fusarium and variation in fungal taxa. Sci. Rep. 8 1–7. 10.1038/s41598-018-35404-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaria A., Johnson C. E., Groffman P. M., Fisk M. C. (2014). Effects of calcium silicate treatment on the composition of forest floor organic matter in a northern hardwood forest stand. Biogeochemistry 122 313–326. 10.1007/s10533-014-0043-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baligar V. C., Fageria N. K., He Z. L. (2001). Nutrient use efficiency in plants. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 32 921–950. 10.1081/CSS-100104098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bastakoti S., Belbase S., Manandhar S., Arjyal C. (2017). Trichoderma species as biocontrol agent against soil borne fungal pathogens. Nepal J. Biotech. 5 39–45. 10.3126/njb.v5i1.18492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bothe H. (2015). The lime-silicate question. Soil Biol. Biochem. 89 172–183. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buée M., Reich M., Murat C., Morin E., Nilsson R. H., Uroz S., et al. (2009). 454 Pyrosequencing analyses of forest soils reveal an unexpectedly high fungal diversity. New Phytol. 184 449–456. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caires E. F., Garbuio F. J., Churka S., Barth G., Corrêa J. C. L. (2008). Effects of soil acidity amelioration by surface liming on no-till corn, soybean, and wheat root growth and yield Eur. J. Agron. 28 57–64. 10.1016/j.eja.2007.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cenini V. L., Fornara D. A., McMullan G., Ternan N., Carolan R., Crawley M. J., et al. (2016). Linkages between extracellular enzyme activities and the carbon and nitrogen content of grassland soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 96 198–206. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.02.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Zhang J. B., Zhao B. Z., Yan P., Zhou G. X., Xin X. L. (2014). Effects of straw amendment and moisture on microbial communities in Chinese fluvo-aquic soil. J. Soils Sediments 14 1829–1840. 10.1007/s11368-014-0924-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dix N. J., Webster J. (1995). Fungal Ecology. London: Chapman &Hall, 549. [Google Scholar]

- Fra̧c M., Jezierska-Tys S., Takashi Y. (2015). Occurrence, detection, and molecular and metabolic characterization of heat-resistant fungi in soils and plants and their risk to human health. Adv. Agron. 132 161–204. 10.1016/bs.agron.2015.02.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Francioli D., Schulz E., Lentendu G., Wubet T., Buscot F., Reitz T. (2016). Mineral vs. organic amendments: microbial community structure, activity and abundance of agriculturally relevant microbes are driven by long-term fertilization strategies. Front. Microbiol. 7:1446. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatch E. W., duToit L. J. (2017). Limestone-mediated suppression of Fusarium wilt in spinach seed crops. Plant Dis. 101 81–94. 10.1094/pdis-04-16-0423-re [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Z. W., Brenneman T., Bonito G., Smith M. E. (2017). Soil pH and mineral nutrients strongly influence truffles and other ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with commercial pecans (Carya illinoinensis). Plant Soil. 418 493–505. 10.1007/s11104-017-3312-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire R., Machado S., Bista P. (2017). Soil pH, soil organic matter, and crop yields in winter wheat-summer fallow systems. Agron. J. 109 706–717. 10.2134/agronj2016.08.0462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gohl D., Vangay P., Garbe J., MacLean A., Hauge A., Becker A., et al. (2016). Systematic improvement of amplicon marker gene methods for increased accuracy in microbiome studies. Nat. Biotechnol. 34 942–949. 10.1038/nbt.3601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Wang G., Wu Y., Shi Y., Feng Y., Cao F. (2019). Ginkgo agroforestry practices alter the fungal community structures at different soil depths in Eastern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26 21253–21263. 10.1007/s11356-019-05293-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydari A., Pessarakli M. (2010). A review on biological control of fungal plant pathogens using microbial antagonists. J. Biol. Sci. 10 273–290. 10.3923/jbs.2010.273.290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J. E., Bennett A. E., Newton A. C., White P. J., McKenzie B. M., George T. S., et al. (2018). Liming impacts on soils, crops and biodiversity in the UK: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 610–611 316–332. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q., Kirk M. F. (2018). pH as a primary control in environmental microbiology: 1. thermodynamic perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 6:21. 10.3389/fenvs.2018.00021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. L., Cooledge E. C., Hoyle F. C., Griffiths R. I., Murphy D. V. (2019). pH and exchangeable aluminum are major regulators of microbial energy flow and carbon use efficiency in soil microbial communities. Soil Bio. Biochem. 138:107584. 10.3389/fenvs.2018.00101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. P., Woltz S. S., Everett P. H. (1975). Effect of liming and nitrogen source on Fusarium wilt of cucumber and watermelon. Proc. Florida State Hortic. Soc. 88 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Karim N. F., Mohd M., Nor N. M., Zakaria L. (2016). Saprophytic and potentially pathogenic Fusarium species from peat soil in Perak and Pahang. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 27 1–20. 10.21315/tlsr2016.27.2.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmitt S. J., Wright D. K., Goulding W. T., Jones D. L. (2006). pH regulation of carbon and nitrogen dynamics in two agricultural soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38 898–911. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler R. M., Maul J. E., Rehner S. A. (2017). Managing the plant microbiome for bio-control fungi: examples from Hypocreales. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 37 48–53. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd P. S., Proctor J. (2001). Why plants grow poorly on very acid soils: are ecologists missing the obvious? J. Exp. Bot. 52 791–799. 10.1093/jexbot/52.357.791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjøller R., Clemmensen K. E. (2009). Belowground ectomycorrhizal fungal communities respond to liming in three southern Swedish coniferous forest stands. For. Ecol. Manag. 257 2217–2225. 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.02.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klaubauf S., Inselsbacher E., Zechmeisterboltenstern S., Wanek W., Gottsberger R., Strauss J., et al. (2010). Molecular diversity of fungal communities in agricultural soils from Lower Austria. Fungal Divers. 44 65–75. 10.1007/s13225-010-0053-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko D., Yoo G., Yun S., Jun S., Chung H. (2017). Bacterial and fungal community composition across the soil depth profiles in a fallow field. J. Ecology Environ. 41:34. 10.1186/s41610-017-0053-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig R. T., Schroeder K., Carter A., Pumphrey M., Paulitz T., Campbell K., et al. (2013). Soil Acidity and Aluminum Toxicity in the Palouse Region of the Pacific Northwest. Pullman, WA: Washington State University Extension. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsyurbenko O. R., Chin K.-J., Glagolev M. V., Stubner S., Simankova M. V., Nozhevnikova A. N., et al. (2004). Acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic methane production and methanogenic populations in an acidic West-Siberian peat bog. Environ. Microbiol. 6 1159–1173. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00634.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber C. L., Hamady M., Knight R., Fierer N. (2009). Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 5111–5120. 10.1128/AEM.00335-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leprince F., Quiquampoix H. (1996). Extracellular enzyme activity in soil: effect of pH and ionic strength on the interaction with montmorillonite of two acid phosphatases secreted by the ectomycorrhizal fungus Hebeloma cylindrosporum. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 47 511–522. 10.1111/j.1365-2389.1996.tb01851.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R. W., Barth V. P., Coffey T., McFarland C., Huggins D. R., Sullivan T. S. (2018). Altered bacterial communities in long-term no-till soils associated with stratification of soluble aluminum and soil pH. Soil Syst. 2 1–13. 10.3390/soils201000731276103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Chen L., Redmile-Gordon M., Zhang J. B., Zhang C. Z., Ning Q., et al. (2018). Mortierella elongata’s roles in organic agriculture and crop growth promotion in a mineral soil. Land. Degrad. Dev. 29 1642–1651. 10.1002/ldr.2965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Sun J., Wang H., Li X., Wang J., Zhang H. (2017). Changes in the soil microbial phospholipid fatty acid profile with depth in three soil types of paddy fields in China. Geoderma 290 69–74. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.11.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Ye G., Liu D., Ledgard S., Luo J., Fan J., et al. (2018). Long-term application of lime or pig manure rather than plant residues suppressed diazotroph abundance and diversity and altered community structure in an acidic Ultisol. Soil Biol. Biochem. 123 218–228. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.05.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcot B. G. (2017). A review of the role of fungi in wood decay of forest ecosystems. Res. Note 575 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Maron J. L., Marler M., Klironomos J. N., Cleveland C. C. (2011). Soil fungal pathogens and the relationship between plant diversity and productivity. Ecol. Lett. 14 36–41. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland C., Huggins D. R. (2015). Acidification in the inland Pacific Northwest. Crop. Soils Mag. 48 4–12. 10.2134/cs2015-48-2-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melvin A. M., Lichstein J. W., Goodale C. L. (2013). Forest liming increases forest floor carbon and nitrogen stocks in a mixed hardwood forest. Ecol. Appl. 23 1962–1975. 10.1890/130274.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorhead D. L., Lashermes G., Sinsabaugh R. L. (2012). A theoretical model of C- and N-acquiring exoenzyme activities, which balances microbial demands during decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 53 133–141. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.05.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagati M., Roy M., Desrochers A., Manzi S., Bergeron Y., Gardes M. (2019). Facilitation of balsam fir by trembling aspen in the boreal forest: do ectomycorrhizal communities matter? Front. Plant Sci. 10:932. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendrula-Kotha R., Nkongolo K. K. (2017). Microbial response to soil liming of damaged ecosystems revealed by pyrosequencing and phospholipid fatty acid analyses. PLoS One 12:e0168497. 10.1371/journal.pone.0168497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Q., Chen L., Jia Z., Zhang C., Ma D., Li F., et al. (2020). Multiple long-term observations reveal a strategy for soil pH-dependent fertilization and fungal communities in support of agricultural production. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 293:106837. 10.1016/j.agee.2020.106837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio N. W., Habte M. (2015). Effect of a phosphate-solubilizing fungus and an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on leucaena seedlings in tropical soils with contrasting phosphate sorption capacity. Plant Soil. 389 375–385. 10.1007/s11104-014-2357-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Z., Tayyab M., Kong C., Hu C., Zhu Z., Wei X., et al. (2019). Liming positively modulates microbial community composition and function of sugarcane fields. Agronomy 9 1–17. 10.3390/agronomy9120808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlett M., Hopkins D. W., Moffett B. F., Harris J. A. (2009). The effect of earthworms and liming on soil microbial communities. Biol. Fertil. Soils 45 361–369. 10.1007/s00374-008-0339-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pennanen T. H., Vanhala P., Kiikkila O., Neuvonen S., Baath E. (1998). Structure of a microbial community in soil after prolonged addition of low levels of simulated acid rain. Appl. Environ. Microb. 64 2173–2180. 10.1128/AEM.64.6.2173-2180.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prober S. M., Leff J. W., Bates S. T., Borer E. T., Firn J., Harpole W. S., et al. (2015). Plant diversity predicts beta but not alpha diversity of soil microbes across grasslands worldwide. Ecol. Lett. 18 85–95. 10.1111/ele.12381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousk J., Bååth E., Brookes P. C., Lauber C. L., Lozupone C., Caporaso J. G., et al. (2010). Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 4 1340–1351. 10.1038/ismej.2010.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousk J., Brookes P. C., Bååth E. (2009). Contrasting soil pH effects on fungal and bacterial growth suggest functional redundancy in carbon mineralization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 1589–1596. 10.1128/AEM.02775-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos D. R., Tiecher T., Gonzatto R., Santanna M. A., Brunetto G., Silva L. S. (2018). Long-term effect of surface and incorporated liming in the conversion of natural grassland to no-till system for grain production in a highly acidic sandy-loam Ultisol from South Brazilian Campos. Soil Tillage Res. 180 222–231. 10.1016/j.still.2018.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlatter D. C., Kahl K., Carlson B., Huggins D. R., Paulitz T. (2018). Fungal community composition and diversity vary with soil depth and landscape position in a no-till wheat-based cropping system. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94:fiy098. 10.1093/femsec/fiy098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder J. L., Zhang H., Girma K., Raun W. R., Penn C. J., Payton M. E. (2011). Soil acidification from long-term use of nitrogen fertilizers on winter wheat. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 75 957–964. 10.2136/sssaj2010.0187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder K., Pumphrey M. (2013). It’s All a Matter of pH: Acid Soils, Aluminum Toxicity Are on the Rise in Eastern Washington, Northern Idaho. Pullman, WA: Washington State Crop Improvement Association, Washington Grain Commission reports, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder K. L., Schlatter D. C., Paulitz T. C. (2018). Location-dependent impacts of liming and crop rotation on bacterial communities in acid soils of the. Pac. Northwest Appl. Soil Ecol. 130 59–68. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2018.05.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova T. A., Morgado L. N., Welker J. M., Walker M. D., Smets E., Geml J. (2015). Long-term experimental warming alters community composition of ascomycetes in Alaskan moist and dry arctic tundra. Mol. Ecol. 24 424–437. 10.1111/mec.13045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestro L. B., Stenglein S. A., Forjan H., Dinolfo M. I., Arambarri A. M. (2013). Occurrence and distribution of soil Fusarium species under wheat crop in zero tillage. Span. J. Agric. Res. 11 72–79. 10.5424/sjar/2013111-3081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. E., Read D. J. (1997). Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 2nd Edn, San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 605. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar B., Wilhelm R. C., Debenport S., Goodale C. L., Fahey T., Buckley D. H. (2018). “Liming suppresses decomposition and alters microbial community composition in a northern mixed hardwood forest,” in Proceedings of the American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting, Washington, DC. 2018AGUFM.B33O2878S. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland M. S., Rousk J. (2010). Considering fungal:bacterial dominance in soils - Methods, controls, and ecosystem implications. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42 1385–1395. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.05.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suz L. M., Barsoum N., Benham S., Dietrich H.-P., Fetzer K. D., Fischer R., et al. (2014). Environmental drivers of ectomycorrhizal communities in Europe’s temperate oak forests. Mol. Ecol. 23 5628–5644. 10.1111/mec.12947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagawa M., Tamaki H., Manome A., Koyama O., Kamagata Y. (2010). Isolation and characterization of antagonistic fungi against potato scab pathogens from potato field soils. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 305 136–142. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01928.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C., Rengel Z., Diatloff E., Gazey C. (2003). Responses of wheat and barley to liming on a sandy soil with subsoil acidity. Field Crops Res. 80 235–244. 10.1016/S0378-4290(02)00192-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tedersoo L., Bahram M., Põlme S., Kõljalg U., Yorou N. S., Wije R., et al. (2014). Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 346:1078. 10.1126/science.1256688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedersoo L., Hansen K., Perry B. A., Kjøller R. (2006). Molecular and morphological diversity of pezizalean ectomycorrhiza. New Phytol. 170 581–596. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01678.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L. R., Sanders J. G., McDonald D., Amir A., Ladau J., Locey K. J., et al. (2017). A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature 551:457. 10.1038/nature24621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Uexküll H. R., Mutert E. (1995). Global extent, development and economic impact of acid soils. Plant Soil 171 1–15. 10.1007/978-94-011-0221-6_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wan S., Liu Z., Chen Y., Zhao J., Ying Q., Liu J. (2019). Effects of lime application and understory removal on soil microbial communities in subtropical Eucalyptus L’Hér. plantations. Forests 10 1–12. 10.3390/f10040338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhang W., Shao Y., Zhao J., Zhoud L., Zoue X., et al. (2019). Fungi to bacteria ratio: historical misinterpretations and potential implications. Acta Oecol. 95 1–11. 10.1016/j.actao.2018.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Web Soil Survey. (2013). United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Washington, DC, Available online at: http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/WebSoilSurvey.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka T. (2003). The effect of pH on the growth of saprotrophic and ectomycorrhizal ammonia fungi in vitro. Mycologia 95 584–589. 10.2307/3761934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye G., Lin Y., Luo J., Di H. J., Lindsey S., Liu D., et al. (2020). Responses of soil fungal diversity and community composition to long-term fertilization: field experiment in an acidic Ultisol and literature synthesis. Appl. Soil Ecol. 145:103305. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye R., Jin Q., Bohannan B., Keller J. K., McAllister S. A., Bridgham S. D. (2012). pH controls over anaerobic carbon mineralization, the efficiency of methane production, and methanogenic pathways in peatlands across an ombrotrophic–minerotrophic gradient. Soil Biol. Biochem. 54 36–47. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.05.015 22960065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Chen L., Pan S., Li Y., Kuzyakov Y., Xu J., et al. (2018). Feedstock determines biochar-induced soil priming effects by stimulating the activity of specific microorganisms. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 69 521–534. 10.1111/ejss.12542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Feng H., Wang L., Li Z., Shi Y., Zhao L., et al. (2017). Potential of endophytic fungi isolated from cotton roots for biological control against verticillium wilt disease. PLoS One 12:e0170557. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zhou X., Tian L., Ma L., Luo S., Zhang J., et al. (2017). Fungal communities in ancient peatlands developed from different periods in the Sanjiang Plain, China. PLoS One 12:e0187575. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang W. Y. (2000). Two new species of Unguiculariopsis (Helotiaceae, Encoelioideae) from China. Mycol. Res. 104 507–509. 10.1017/s0953756299001902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Žifčáková L., Vetrovský T., Howe A., Baldrian P. (2016). Microbial activity in forest soil reflects the changes in ecosystem properties between summer and winter. Environ. Microbiol. 18 288–301. 10.1111/1462-2920.13026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Venn diagram of OTUs influenced by liming treatments among soil depths. (A) Pendleton, (B) Moro.

Soil pH changes after lime amendments at two wheat locations. Soil depth: 0–7.5 cm, 7.5–15 cm, and 15–22.5 cm. The values are means (n = 32) ± SE. Different letters represent significant differences (p ≤ 0.05, Tukey test).

Heatmap of significant Spearman correlations between soil chemical characteristics and soil depth and location. OM, organic matter; Al-DTPA, DTPA extractable aluminum; Al-KCl, KCl extractable aluminum; CEC, cation exchange capacity and the element listed before CEC (i.e., Ca.CEC) represents the proportion of the CEC comprised of that specific cation. Significance was examined using R statistical software (p ≤ 0.05 and absolute r value cut off 0.3).

Heatmap of significant Spearman correlations between fungal family abundance and soil chemical characteristics at different soil depths. OM, organic matter; Al-KCl, KCl extractable aluminum; Al-DTPA, DTPA extractable aluminum; CEC, cation exchange capacity and the element listed before CEC (i.e., Ca.CEC) represents the proportion of the CEC comprised of that specific cation. Significance was determined using R statistical software (p ≤0.05 and absolute r-value cut off 0.3).

Data Availability Statement

The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA678975.