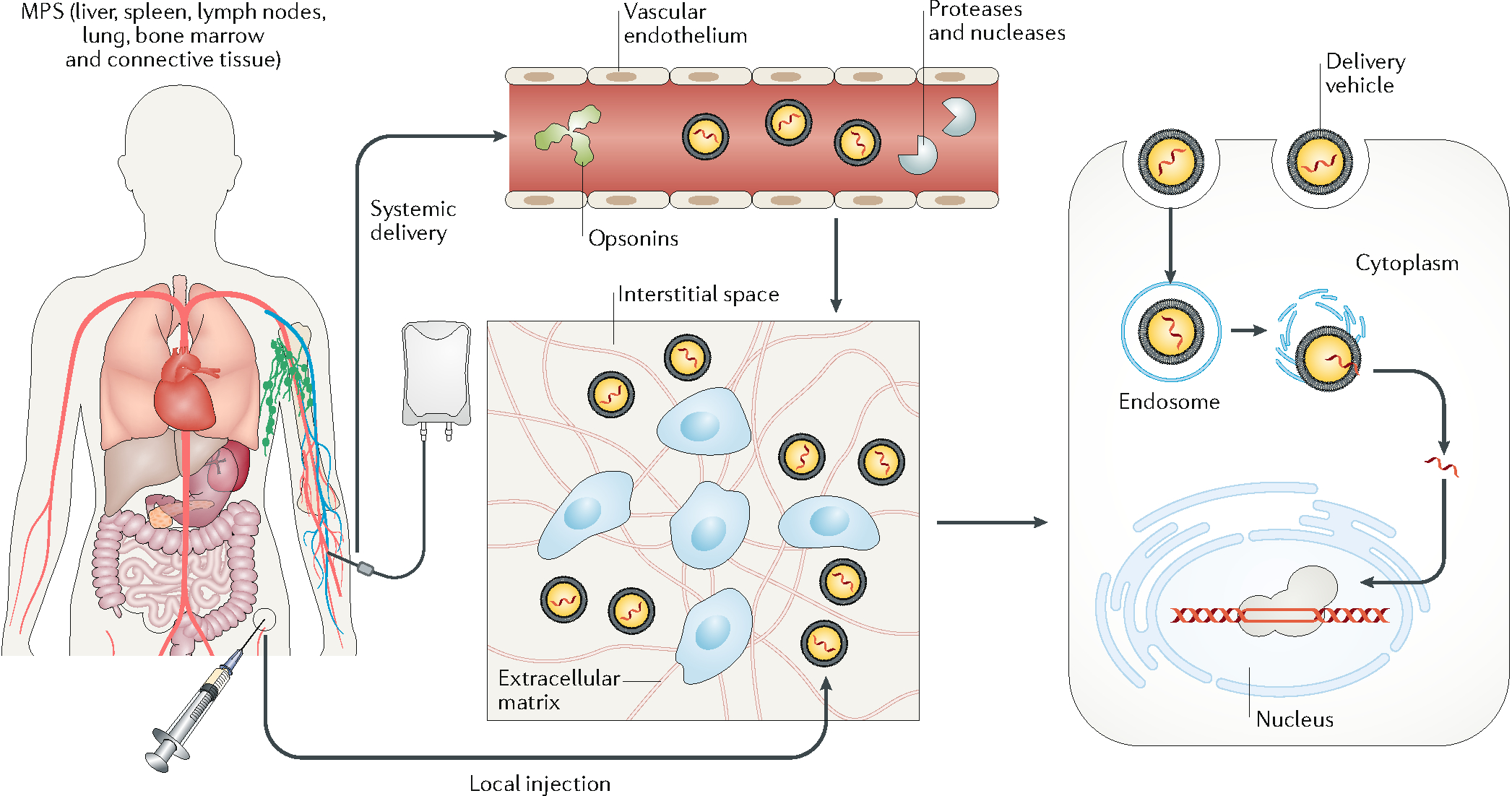

Figure 1. Biological barriers to in vivo delivery from systemic circulation to cell nucleus.

In systemic delivery, the delivery vehicles are distributed throughout the body. To edit target cells, the delivery vehicles need to extravasate, travel across the interstitial space, and pass through the cell membrane into the cell nucleus. With local injection, the delivery vehicles enter the interstitial space directly. In systemic delivery, the delivery vehicles can adsorb opsonins, including antibodies, complement factors, and other proteins in the plasma, which promote their clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system. In addition, exposure of the genome-editing machinery to the plasma can cause degradation via circulating proteases or nucleases. Another barrier to systemic delivery is the vascular endothelium (unless it is the target tissue). In most tissues, the endothelial cells on the vessel surface are connected to form a continuous layer via cell–cell junctions, which prevents most delivery vehicles from entering the interstitial space. The interstitial transport of delivery vehicles is often hindered by the stroma cells and the extracellular matrix, which may confine systemically delivered vehicles close to the vessel surface and locally injected vehicles to the site of injection. Another rate-limiting step is for the delivery vehicles to pass through the cell membrane via micropinocytosis or endocytosis. The delivery vehicles entering the cells are typically transported from endosomes to lysosomes, where most proteins and nucleic acids are enzymatically digested. Therefore, cargo needs to be released from the delivery vehicle and escape from the endosome to enter the cytosol. Finally, the cargo needs to enter the cell nucleus to perform gene editing at the target locus (except for the case of RNA editing in the cytosol).