Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is characterized by altered epithelial cell phenotypes, which are associated with myofibroblast accumulation in the lung. Atypical alveolar epithelial cells in IPF express molecular markers of airway epithelium. Polymorphisms within and around Toll interacting protein (TOLLIP) are associated with the susceptibility to IPF and mortality. However, the functional role of TOLLIP in IPF is unknown. Using lung tissues from IPF and control subjects, we showed that expression of TOLLIP gene in the lung parenchyma is globally lower in IPF compared to controls. Lung cells expressing significant levels of TOLLIP include macrophages, alveolar type II and basal cells. TOLLIP protein expression is lower in the parenchyma of IPF lungs but is expressed in the atypical epithelial cells of the distal fibrotic regions. Using overexpression and silencing approaches, we demonstrate that TOLLIP protects cells from bleomycin induced apoptosis using primary bronchial epithelial cells and BEAS-2B cells. The protective effects are mediated by reducing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and upregulating autophagy. Therefore, global down regulation of the TOLLIP gene in IPF lungs may predispose injured lung epithelial cells to apoptosis and to the development of IPF.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, TOLLIP, apoptosis, autophagy, lung epithelial cells, basal cells

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a deadly disease with a median survival time of 3 years after diagnosis (1). IPF is characterized by the loss of alveolar epithelium and the accumulation of myofibroblasts which is attributable to aberrant injury/repair response to repetitive insults (2–4). Atypical epithelial cells expressing molecular markers of airway epithelium in the distal fibrotic lungs have emerged as important players in the pathogenesis of IPF (5–8). Genetic mutations in epithelial cell-specific genes including surfactant protein C (SFTPC), SFTPA1, SFTPA2, ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 3 (ABCA3) and genes related to telomere length have been identified in familial cases of IPF (9–14) and are associated with cellular stress and senescence (15). A common promoter variant in an airway epithelial cell expressing gene, the mucin 5B (MUC5B), is associated with both IPF development and better outcome of IPF patients (16–20). Adjacent to MUC5B on chromosome 11 is toll interacting protein (TOLLIP). Polymorphisms in both TOLLIP and MUC5B are associated with IPF and whether these genes function independently or are in linkage disequilibrium is controversial (19, 21). We therefore performed this study to examine the function of TOLLIP in human lungs and lung diseases.

TOLLIP is a multitasking protein that plays roles in important signaling pathways associated with lung diseases including IL-1β, IL-13, toll-like receptor (TLR) and TGF-β (22–24). We showed previously that variants rs111521887 and rs5743894, located within the introns of TOLLIP, are associated with 40–50% decreased TOLLIP gene expression in the lung and susceptibility to IPF (19). The intronic variant rs5743890 within TOLLIP is protective for IPF susceptibility but is associated with more IPF mortality (19). Interestingly, rs5743890 is also associated with 20% decreased TOLLIP gene expression in the lung (19). TOLLIP protein is a ubiquitin-binding protein and facilitates TLR and TGF-β type 1 receptor intracellular localization and lysosomal degradation (22–24). TOLLIP also exerts its anti-apoptosis and pro-autophagy effects through interaction with target of Myb membrane trafficking protein 1 (TOM1) in the context of autoimmunity (25). TOLLIP protects intestinal epithelial cells from apoptosis induced by IFN-γ and TNF-α signaling (26). TOLLIP also acts as a cargo adaptor linking autophagy gene 8 (ATG8)/microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 (MAP1LC3A) coated autophagosomes to ubiquitin-modified protein aggregates, and plays a critical role in autophagic clearance of cytotoxic protein aggregates (27).

We analyzed the expression levels of TOLLIP in both IPF and control lungs. We determined cell types expressing TOLLIP gene using single cell RNA sequencing. We tested the hypothesis that TOLLIP protects lung epithelial cells from environmental and chemical insults induced cell death in primary human bronchial epithelial cells. We further performed mechanistic studies on TOLLIP protective effects using a lung epithelial cell line, BEAS-2B. Together, our data demonstrate the cell-type specific roles of TOLLIP and support that TOLLIP is a survival factor that protect bronchial epithelial cells from injury-induced cell death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Primary human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells were isolated and cultured from excess pathologic tissue after lung transplantation or donated organs not suitable for transplantation from the Center for Organ Recovery and Education, under a protocol approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, as previously described (28). The HBE cells were cultured in completed BronchiaLife epithelial airway medium (Lifeline cell technology). BEAS-2B (CRL-9609) and 293T (CRL-3216) cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12 medium at a 1:1 ratio and DMEM, respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technology). All cells were grown in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Plasmid constructs and inducible TOLLIP overexpression BEAS-2B cells

The full-length cDNA of TOLLIP gene was amplified using cDNA from normal human blood cells (Primers:5′-ACCATGGCGACCACCGTCAG-3′; 5′-TGGCTCCTCCCCCATCTGCAG-3′). The cDNA was subsequently cloned into pcDNA3.1D/V5-His-TOPO vector to generate TOLLIP-V5 plasmid. To generate inducible TOLLIP overexpressing cells, we subcloned the TOLLIP cDNA into pCW57-GFP-2A-MCS using Gibson assembly and packaged lentiviral particles in 293T cells using psPAX2 and pMD2.G packaging plasmids. An inducible TOLLIP overexpressing cell line was generated by infecting BEAS-2B cells with TOLLIP-expressing lentivirus followed by puromycin selection (2 μg/ml). At 48 hours, the selected cells were harvested as a polyclonal inducible TOLLIP overexpressing BEAS-2B cell line and used for TOLLIP overexpression experiments.

Silencing and overexpression of TOLLIP

TOLLIP gene in primary HBE and BEAS-2B cells was knocked down using Stealth siRNA duplex oligoribonucleotides specific for human TOLLIP (5’-CCAAGAAUUACGGCAUGACCCGCAU-3’; 5’-AUGCGGGUCAUGCCGUAAUUCUUGG-3’) obtained from Invitrogen. Scramble siRNA oligonucleotides were used as controls. Transfection of siRNA was performed using GenMute transfection reagent (SignaGen Laboratories). For transient overexpression of TOLLIP in BEAS-2B and primary HBE cells, TOLLIP-V5 plasmid was transfected into these cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). To induce TOLLIP expression in the stable inducible BEAS-2B cells, the cells were treated with doxycycline (Sigma) at 2 μg/ml for 48 hours before experiment. Both overexpression and knocking down of TOLLIP protein in treated cells were confirmed by immunoblotting.

Mt-keima reporter BEAS-2B cells and live cell imaging

The plasmid pLVX-mt-Keima is a generous gift of Dr. Toren Finkel, MD, PhD, University of Pittsburgh. Lentiviral particles of pLVX-mt-Keima were packaged in 293T cells using psPAX2 and pMD2.G plasmids and used for transfecting BEAS-2B cells. A polyclonal mt-Keima reporter BEAS-2B cell line was generated after 48 hours of puromycin selection (2 μg/ml) and used for the live cell imaging experiments. A non-inducible TOLLIP lentivirus created using Lenticas9 blast vector and Gibson assembly was used for overexpressing TOLLIP in these cells. Knocking down of TOLLIP expression was achieved using siRNA. The cells were treated with either PBS (control) or bleomycin at 50 μM for overnight and live cell imaging was performed using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope with 60 × objective in two channels and two sequential excitation lasers (459 and 562 nm). Changes in xy-position were made manually. Images from 14 (overexpression experiments) or 9 (knocking down experiments) representative fields were taken for each condition and the positive spots for fluorescence Green (without fusion with lysosome) and Red (fusion of mitochondria and lysosome) were counted for each field. To determine the degree of mitophagy in each condition, ratio of florescence Red/Green was calculated and compared between control vector lentivirus and TOLLIP-lentivirus, and between scramble siRNA and TOLLIP siRNA used student T-test.

Isolation of cytosolic fraction

Cytosol of cultured cells were obtained using Mitochondria/Cytosol isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Western Blot

Human lung tissues were obtained from excess pathologic tissue after lung transplantation and organ donation as described above (28, 29). For the bafilomycin A1 (Sigma, B1793) treatments, cells were treated with 20 μM bafilomycin A1 for 4 hours prior to cell lysate preparation. For mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger experiments, cells were pretreated with mitoTEMPO at specified concentrations (Enzo, ALX-430–150-M005) for 1 hour prior to and during the bleomycin treatment. Lung tissues or whole-cell lysates were prepared by homogenization in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad), and blocked in 5% milk prior to primary antibody binding. Primary antibodies used in this study were specific for TOLLIP (Sigma, HPA038621), V5 (Invitrogen, R960–25), Tubulin (Abcam, ab184970), and for Caspase-3 (D3R6Y), cleaved Caspase-3 (5A1E), Cytochrome C, MAP1LC3A/B (LC3A/B), and Flag from Cell Signaling (Catalogue # 14220, 9664, 11940, 12741, and 14793, respectively). Goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (sc2005) and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (sc2004) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibody specific for housekeeping gene β-Actin (Sigma, 5441) and GAPDH (Abcam, ab125247) were used to determine sample loading. Blots were developed using HRP-substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and imaged using Amersham Imager 680 (GE Health). Densitometry was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) (30).

Co-Immunoprecipitation

BEAS-2B cells were transiently transfected with TOLLIP-V5 plasmid. At 24 hours post transfection, whole cell lysate was collected by BlastR lysis buffer (Cytoskeleton) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail and N-ethylmaleimide. Cell lysate was pre-incubated with 20 μl Dynabeads protein A (Invitrogen) for 1 hour. Supernatant was split into 2 tubes, incubated with either 4 μg antibody specific for V5 (Invitrogen) or mouse control isotype IgG (Cell signaling) overnight at 4 °C with shaking. The following day, 20 μl Dynabeads protein A were added and incubated for 2 hours. Proteins were eluted, separated using 10% SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred to PVDF membrane. Immunoblot analysis was performed using primary antibody specific for V5 and LC3 A/B.

Immunohistochemistry

Serial sections of frozen lung tissue were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS (Santa Cruz, 30525-89-4) for 10 minutes, followed by 10-minute incubation with 0.1% Triton X100 in PBS for permeabilization. Donkey serum (5% in PBS, Sigma) was used as a blocking agent to treat tissue sections for 60 minutes. The slides were quenched by 3% peroxidase for 10 minutes, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibody specific for TOLLIP. Secondary antibody incubation was performed at room temperature for 1 hour. The Avidin-Biotin Complex (ABC) kit and DAB substrate (Vector) was used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining.

Immunofluorescence staining

The same frozen tissues described above were used for immunofluorescence staining. Fixation, permeabilization, blocking and primary antibodies incubation were performed as described above. Antibody specific for TOLLIP and E-Cadherin (Cell Signaling) were used as primary antibodies. Anti-rabbit Cy3, anti-mouse Cy5 IgG conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) and DAPI (Sigma) were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour, and then the slides were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen). For negative controls, slide sections were treated with 5% donkey serum instead of the primary antibody. Tissue image was captured using Nikon A1 confocal microscope using a 40 × objective.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from lung tissues or cultured cells using the TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen). Complementary DNA was synthesized using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR of target genes were performed using a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System and Taqman gene-specific primer probe set Hs01553185_m1 for TOLLIP, Hs03929097_g1 for GAPDH, Hs01076567_g1 for MAP1LC3A and Hs00797944_s1 for MAP1LC3B. The GAPDH gene was used as an internal control.

Single cell RNA sequencing analysis

Single cell RNA sequencing dataset of 3 control lungs, donor lungs not suitable for lung transplant, and 3 paired upper and lower explanted IPF lungs (GEO Accession GSE128033) was used for analyzing cell-type specific TOLLIP expression using the exact method described (31). Lung tissue collection, single cell isolation, sequencing, data cleaning, normalization, clustering, and cluster identification was described in detail in the original study (31). Violin plots were generated using the Seurat package in R.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay

Primary HBE cells were grown on cover glasses (Fisher Scientific#12-545-82). TUNEL assay was carried out using In Situ cell Death Detection Kit (Roche #11684795910). Positive fluorescein stained cells and DAPI stained nuclei were detected using Nikon A1 confocal microscope.

Mitochondrial ROS measurements

Mitochondrial ROS production was measured by MitoSOX Red fluorescence. Inducible TOLLIP overexpressing cells and control cells were setup in 6 well plate at a 2 × 105/well, treated by doxycycline at 2 μg/ml for 48 hours. For the knocking down experiment, BEAS-2B cells were seeded in 6 well plate at a 4 × 105/well, transfected with TOLLIP siRNA and scramble siRNA for 48 hours. Then all cells were treated with either PBS (control) or bleomycin at 50 μM (Sigma B8416) for 8 hours. After treatment, cells were collected and resuspended in 20 μl culture media. Cell suspension were transferred into each well (10 μl/well) of a 96-well plate and incubated with MitoSOX (10 nM, Invitrogen,) for 10 minutes. The cells were washed with PBS and fluorescent intensity (510/580 nm) was measured kinetically. The fluorescent intensity of each well was normalized by total protein measured using BCA protein concentration kit (Thermo Scientific).

Statistical Analysis

Standardized expression levels of TOLLIP in the LGRC dataset were used for the IPF and control comparison using non-parametric Mann-Whitney t-test. For the quantitative RT-PCR analysis of TOLLIP expression in lung tissues, normalized expression levels by GAPDH were used and analyzed as described above. Densitometry quantification of immunoblot bands were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney t-test. The group comparisons (with or without bleomycin treatment) for each condition in the mt-Keima experiments were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney t-test. All analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 7 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

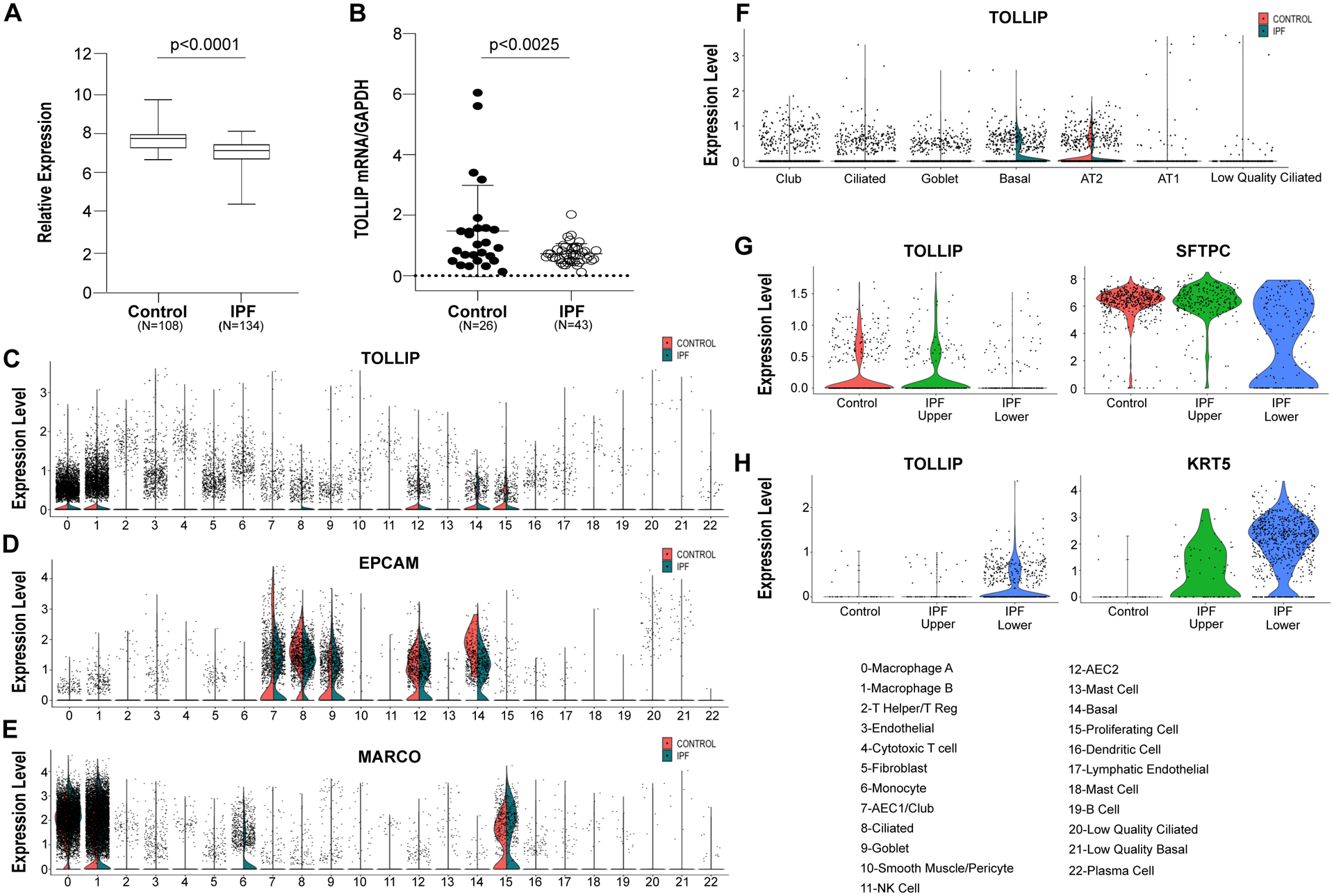

TOLLIP gene expression is down regulated in IPF lungs

To determine lung tissue expression of TOLLIP gene, we analyzed expression levels of TOLLIP in IPF and control lungs from the Lung Genomics Research Consortium (LGRC) gene expression dataset (http://www.lung-genomics.org) (32, 33). TOLLIP expression was significantly lower in IPF compared to control lungs (Fig. 1A). We further validated the down regulation of TOLLIP using quantitative PCR analysis of mRNA isolated from parenchyma of explanted IPF lungs compared to control donor lungs that were deemed not suitable for transplant (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Lung-specific expression of TOLLIP gene.

(A) Gene expression data from the Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LGRC) were analyzed for TOLLIP expression levels. The study included 108 control subjects and 134 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). (B) TOLLIP gene expression levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from parenchyma of IPF lungs (n=43) and control donor lungs (n=26). Values are means and standard deviation (SD). Non-parametric Mann-Whitney t-test was used to compare groups. Cell type specific expression of TOLLIP based on a single cell RNA sequencing study of 3 IPF lungs and 3 control lungs are shown in C-H (31). Violin plots of TOLLIP (C), EPCAM (D) and MARCO (E) expression across all cell clusters as described in the original report (listed on the right) are shown (31). Violin plots of expression levels of TOLLIP in different epithelial cells are shown in F. Control and IPF lungs are labeled with red and light green, respectively. Violin plots of TOLLIP expression in control lungs, IPF upper lobe and IPF lower lobe lungs for SFTPC (G) and KRT5 (H) positive cells are shown.

TOLLIP gene is expressed in lung macrophages and epithelial cells

We next analyzed the cell types expressing TOLLIP gene using a single cell RNA sequencing dataset of 3 control and 3 IPF lungs (31). Using the cell cluster designations as reported in the original publication we found that TOLLIP was expressed in many cell types of the lung (Fig. 1C). It was highly expressed in a subset of epithelial cells which also expressed epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM) (Fig. 1D) and macrophages expressing macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (MARCO) (Fig. 1E). We re-clustered the cells using only EPCAM-expressing epithelial cells in control and IPF (Fig.1F). Further, we analyzed TOLLIP expression in epithelial cells based on control lungs, IPF lung upper lobes (early disease) and IPF lung lower lobes (late disease). TOLLIP expression in SFTPC positive alveolar type 2 cells was observed predominately in the control lungs and IPF upper lobe as very few alveolar type 2 cells were present in the IPF lower lobe (Fig. 1G). Similarly, TOLLIP expression in basal cells marked by keratin 5 (KRT5) expression was mainly in the IPF lower lobe (Fig. 1H) where basal cells predominate (5–8). Therefore, the minimum presence of TOLLIP-expressing alveolar type 2 cells in the IPF lower lobe is consistent with the observed reduced TOLLIP expression by the bulk RNA gene expression analysis described above.

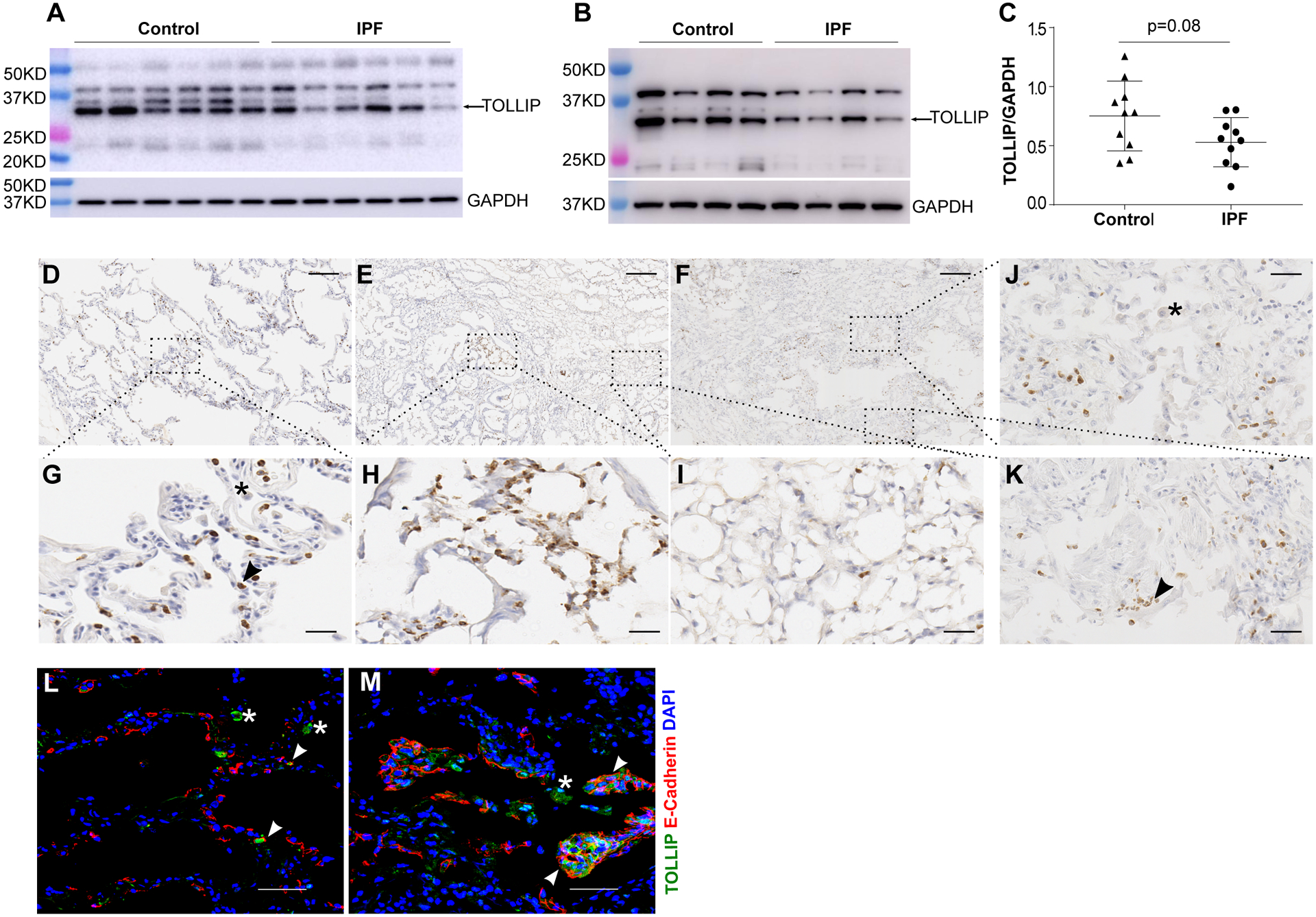

TOLLIP protein is highly expressed in atypical epithelial cells of IPF lungs

We next analyzed TOLLIP expression in the lungs at the protein level. The levels of TOLLIP protein were borderline lower in total protein isolated from the parenchyma of IPF lungs compared to control lungs (P = 0.08, Fig. 2A–C). Using immunohistochemistry (IHC), we found that TOLLIP protein was mainly expressed in a subset of alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages in control lungs (Fig. 2D and 2G). Consistent with the reduced TOLLIP expression in protein lysates of IPF lungs, the overall TOLLIP protein expression was lower in IPF (Fig. 2E–F, and 2I–2K). Similarly, in consistent with the single cell RNA sequencing analysis, TOLLIP expressed abundantly in the distal fibrotic areas within IPF lungs (Fig. 2H) and these cells were also positive for the epithelial cell marker, E-cadherin (Fig. 2 M). Therefore, while the overall expression of TOLLIP protein in IPF lungs is marginally reduced, TOLLIP is specifically expressed in epithelial cells of the distal fibrotic areas.

Figure 2. Lung specific expression of TOLLIP protein.

The levels of TOLLIP protein in IPF (n=10) and control (n=10) lungs were determined by immunoblot (A-B) and normalized by GAPDH (C) using ImageJ software (30). The TOLLIP specific band is indicated by an arrow. Values are means and standard deviation (SD). Non-parametric Mann-Whitney t-test was used to compare groups. Representative immunohistochemistry analysis of human lung tissue samples (n=4 in each group) are shown in D-K. TOLLIP expression in a control lung (D) and two IPF lungs (E-F) are shown with a size bar of 200 microns. Magnified fields of control lung (G) and IPF lungs (H, I, J, K) are shown (size bar = 50 microns). Immunofluorescence staining of TOLLIP and E-cadherin in lung tissues of a control (L) and an IPF patient (M). TOLLIP primary antibody was revealed with Cy3 secondary antibody (pseudo-colored green). E-cadherin was revealed with Cy5 secondary antibody (red) with a size bar of 100 microns. Nuclei were counterstained with the blue fluorescent DNA dye DAPI. Representative macrophages are indicated by asterisk and epithelial cells are indicated by arrowheads.

To further explore the TOLLIP expressing epithelial cells in the fibrotic area, we analyzed the publicly available single cell RNA sequencing datasets using the “IPF cell Atlas Data Mining Site” (https://p2med.shinyapps.io/IPFCellAtlas/). Among the epithelial cell types from the dataset by Morse et al. (GEO Accession GSE128033) (31), TOLLIP was expressed most highly in a cell type assigned as “aberrant basaloid cell” identified in IPF lungs that was distinct from all known epithelial cell types (Fig. S1A). This was validated in the Kaminski/Rosas dataset (GEO Accession GSE136831) of IPF and control lungs (https://doi.org/10.1101/759902, Fig. S1B). Therefore, one of the epithelial cell types expressing TOLLIP in IPF lung is “aberrant basaloid cell”.

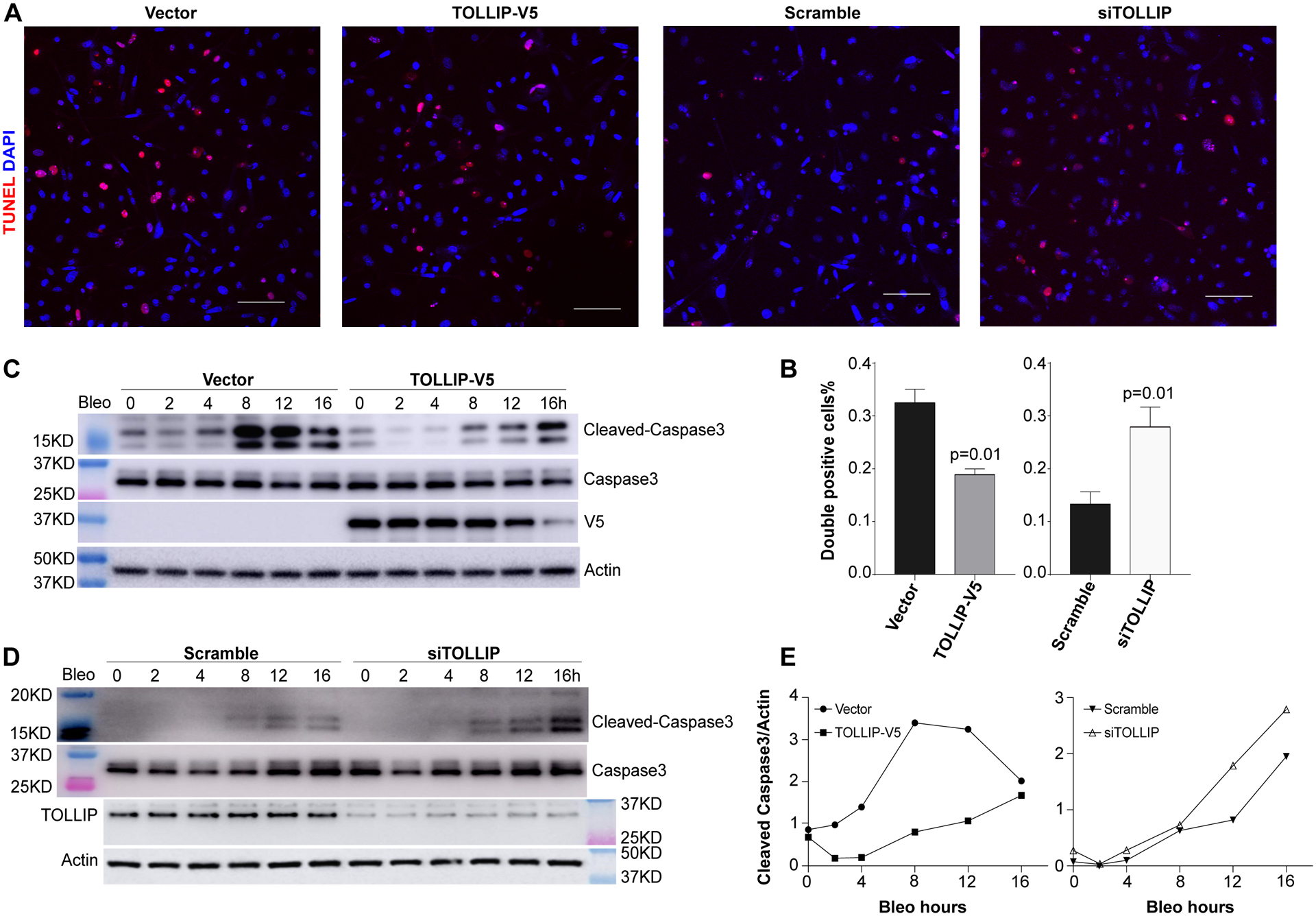

TOLLIP protects bronchial epithelial cells from bleomycin-induced apoptosis

Since TOLLIP protects intestinal epithelial cells from toxin-induced cell death in mice (34), we determined whether TOLLIP protects lung epithelial cells from injury-induced apoptosis, a hallmark of IPF (2). Bleomycin is a widely used experimental agent associated with lung epithelial cell injury, death, and fibrosis (35–38). Bleomycin treatment of primary HBE cells isolated from human donor lungs induced cell death as measured with TUNEL staining (Fig. 3A). Overexpressing a TOLLIP-V5 fusion protein in these cells reduced TUNEL+ cells by 42% (Fig. 3A–B). Similarly, silencing of endogenous TOLLIP expression using siRNA resulted in a 2-fold increase of apoptotic cells compared to cells treated with scramble siRNA control (Fig. 3A–B). To dissect the molecular mechanism of TOLLIP-mediated protection, we further analyzed the changes of apoptosis markers in a lung epithelial cell line, BEAS-2B, a widely used cell line for mechanistic studies of genes related to lung diseases (39–42). Overexpression of the TOLLIP-V5 protein in BEAS-2B cells resulted in a time-dependent decrease of bleomycin-induced caspase-3 protein cleavage up to 12 hours (Fig. 3C and 3E). This effect was diminished at 16 hours when the TOLLIP-V5 expression was noticeably reduced. Consistently, knocking down TOLLIP led to further increase of cleaved-caspase-3 protein compared to scramble siRNA control in cells treated with bleomycin (Fig. 3D and 3E). Furthermore, knockdown of endogenous TOLLIP significantly increased caspase-3 cleavage induced by bleomycin in mouse alveolar epithelial MLE12 cells, although this protective effect was not observed in human primary fetal alveolar epithelial cells (Fig. S2).

Figure 3. TOLLIP protects bronchial epithelial cells from bleomycin induced apoptosis.

Immunofluorescence (A) and quantitative analysis (B) of double positive TUNEL (red) and DAPI (blue) in primary human bronchial epithelial cells treated with bleomycin (50 μM for overnight). Immunoblot analyses of apoptosis marker caspase-3 and its cleaved forms in BEAS-2B cells overexpressing TOLLIP-V5 compared to vector control (C) and TOLLIP siRNA knocking down compared to scramble siRNA (D) are shown. Three independent experiments were performed. Results from a representative experiment are shown. TOLLIP-V5 overexpression and knocking down of endogenous TOLLIP protein are shown in (C) and (D), respectively. Quantifications of the immunoblot in (C) and (D) normalized by actin using ImageJ software (30) are shown in (E).

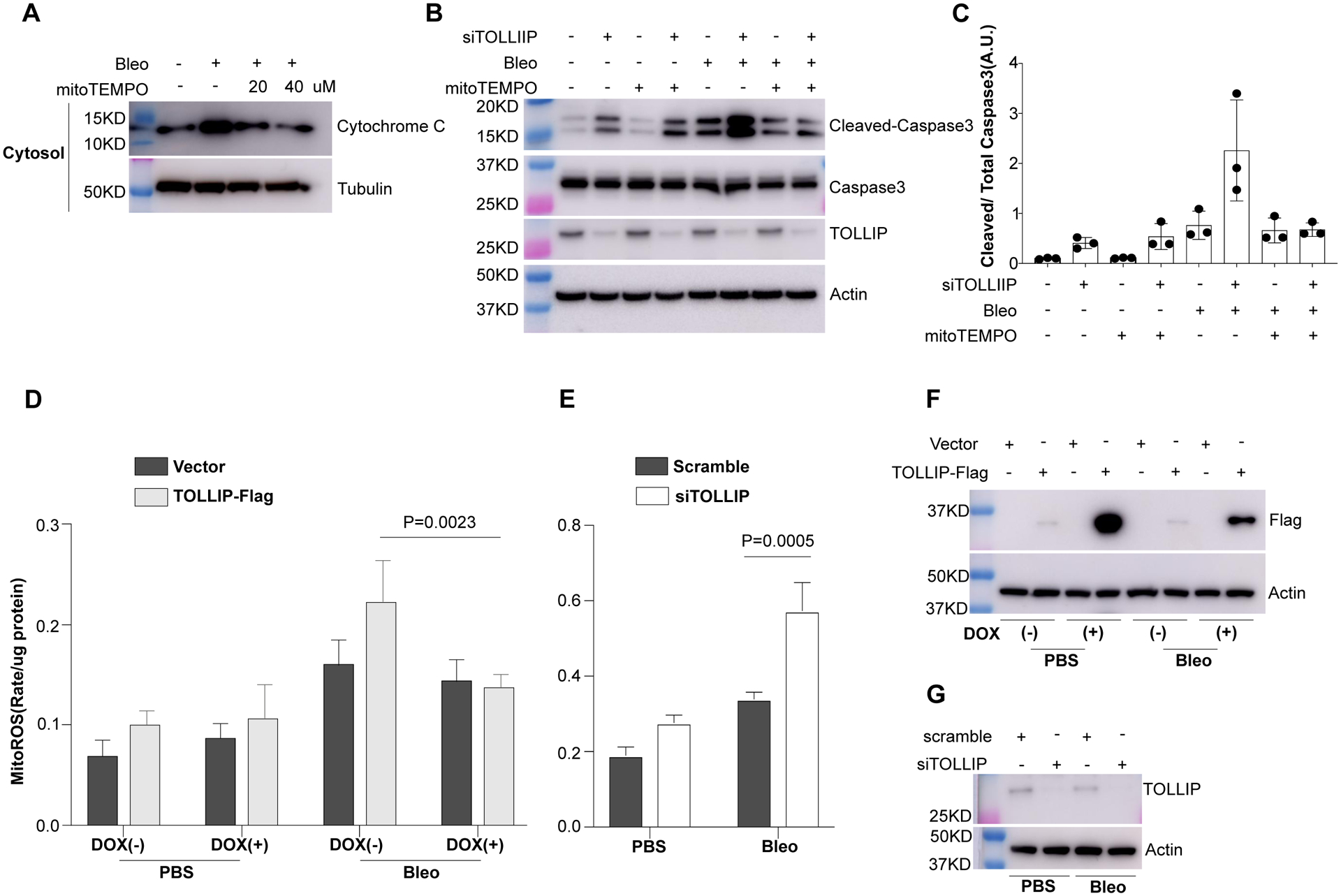

TOLLIP reduces apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway by reducing mitochondrial ROS levels

Since TOLLIP expression is detected in the “aberrant basaloid cells” in the IPF lung and abnormal epithelial cell repair (43–45) is associated with distal “bronchiolization” in IPF (46–49), we performed this proof of concept study using bronchial epithelial cells to dissect the cytoprotective function of TOLLIP. To determine whether bleomycin induced bronchial epithelial cell apoptosis is mediated by ROS, we analyzed dose-dependent effects of mitochondrial ROS scavenger mitoTEMPO in BEAS-2B cells. Bleomycin treatment resulted in increased release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into cytosol while mitoTEMPO blocked cytochrome c release in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Similarly, mitoTEMPO pre-treatment blocked caspase-3 cleavage induced by bleomycin and abolished further increase of caspase-3 cleavage resulting from silencing of TOLLIP in these cells (Fig. 4B). The levels of mitochondrial ROS in these cells were determined using MitoSOX assay. We established a doxycycline-inducible BEAS-2B cell line for overexpressing a TOLLIP-Flag fusion gene or a vector control. In the absence of bleomycin, doxycycline induction of TOLLIP did not increase the total ROS levels in both the vector control and TOLLIP-Flag cells (Fig. 4C). In contrast, bleomycin treatment increased ROS levels in both cells. Induction of TOLLIP-Flag by doxycycline dramatically reduced bleomycin-mediated ROS increase in TOLLIP-Flag cells but not in vector control cells (Fig. 4C). Knocking down TOLLIP increased ROS levels in BEAS-2B cells while scramble siRNA control did not show any effect (Fig. 4D). Both overexpression and knocking down of TOLLIP in these cells were confirmed by Immunoblot (Fig. 4E–F). Therefore, TOLLIP-mediated protection of bleomycin induced lung epithelial cell apoptosis is through reducing mitochondrial ROS accumulation.

Figure 4. TOLLIP protect lung epithelial cells from bleomycin induced apoptosis by reducing mitochondrial ROS levels.

BEAS-2B cells were used for all the experiments. (A) Immunoblot analysis of cytosolic cytochrome c release after bleomycin (50 μM for overnight) and dose dependent reduction of cytochrome c by mitoTEMPO pretreatment. (B) Immunoblot analysis of apoptosis marker cleaved caspase-3 under basal condition and bleomycin alone as well as in combination with mitoTEMPO as indicated. The band densities of cleaved caspase-3 and total caspase-3 in each condition in (B) were quantified from three independent experiments using ImageJ software [30] and the cleaved/total caspase-3 ratios are shown in (C). Mitochondrial ROS production was measured by mitoSOX assay (three independent experiments performed in duplicate) when TOLLIP was overexpressed (D) using a doxycycline inducible TOLLIP-Flag BEAS-2B cell line or knocking down with siRNA (E). As controls, basal levels of ROS were analyzed in the inducible TOLLIP-Flag cell line under doxycycline alone. Overexpression of exogenous TOLLIP-Flag protein and knocking down of endogenous TOLLIP were confirmed by immunoblot as shown in (F) and (G), respectively.

Autophagy is required for TOLLIP-mediated protective effects of bleomycin induced apoptosis

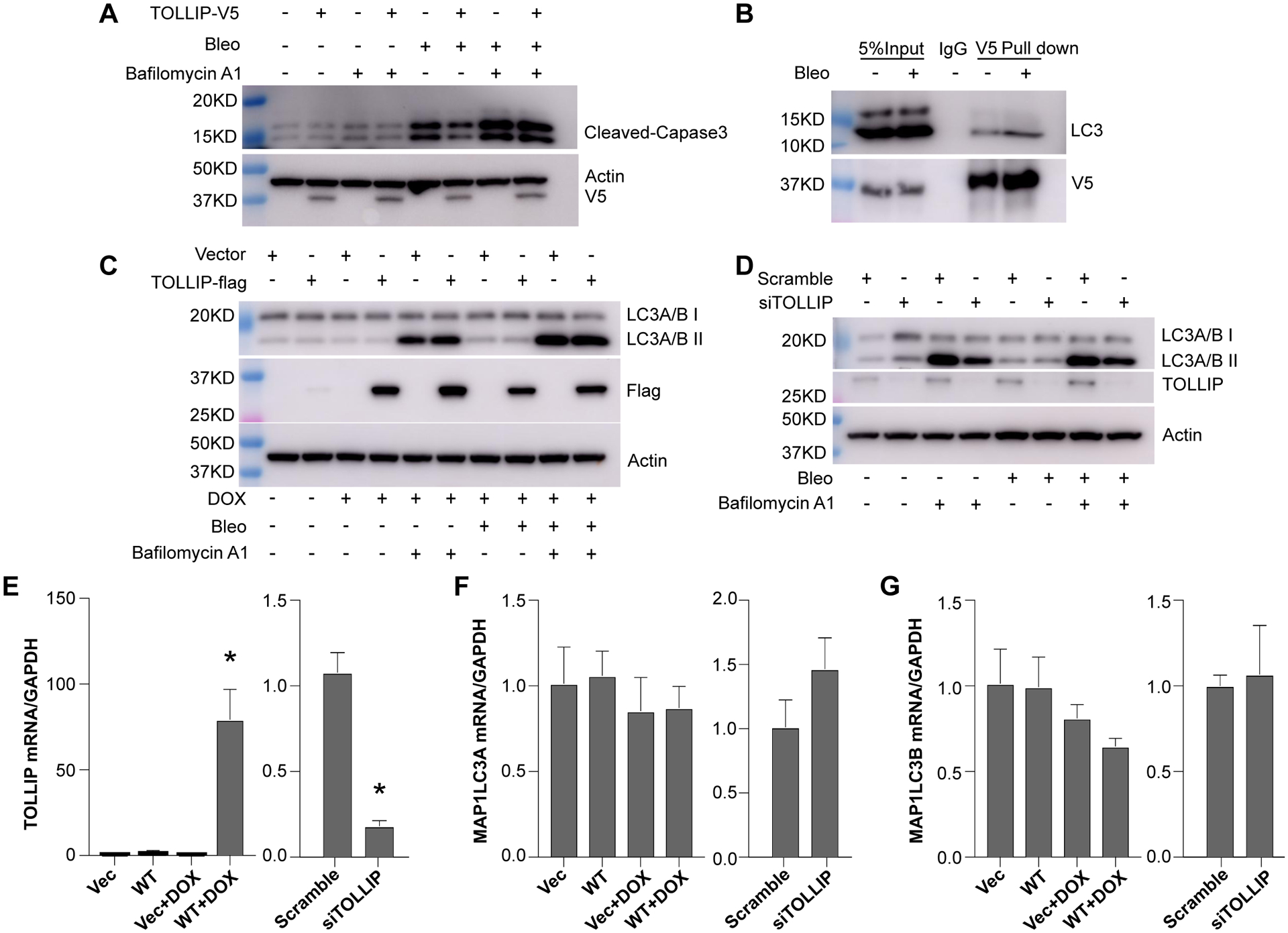

Since apoptosis and autophagy interact with each other (50, 51), we determine whether autophagy plays a role in TOLLIP protection of bleomycin-induced apoptosis. We pretreated the cells with autophagy inhibitor bafilomycin A1 and analyzed caspase-3 cleavage in BEAS-2B cells. Bafilomycin A1 abolished TOLLIP-mediated reduction of bleomycin-induced caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 5A, lane 6 verses lane 8). Immunoprecipitation of TOLLIP-V5 showed that autophagy marker LC3A/B interacted with TOLLIP (Fig. 5B). We further observed dramatic increases of LC3A/B II in both TOLLIP and vector control cells pretreated with bafilomycin A1 and bleomycin challenge further increased LC3A/B II levels (Fig. 5C). However, overexpression of TOLLIP-V5 did not have effects on the increased levels of LC3A/B II in bleomycin and bafilomycin treated cells. In contrast, compared to cells treated with scramble siRNA, silencing of TOLLIP dramatically reduced the increased LC3A/B II levels in bafilomycin A1 with or without bleomycin treatment (Fig. 5D). The increases in LC3A/B II levels in TOLLIP overexpression system were not due to transcriptional upregulation of either MAP1LC3A or MAP1LC3B gene (Fig. 5F–G), Similarly, TOLLIP knocking down with siRNA did not affect the transcription levels of both genes (Fig. 5F–G). Therefore, autophagy is required for TOLLIP-mediated protection of bleomycin induced apoptosis in lung epithelial cells.

Figure 5. TOLLIP is involved in autophagosome formation that is required for TOLLIP protection of lung epithelial cells from bleomycin induced apoptosis.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of cleaved caspase-3 in BEAS-2B cells overexpressing TOLLIP-V5 and treated with bleomycin and bafilomycin A1 as indicated. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of TOLLIP-V5 protein with a specific antibody to V5 in BEAS-2B cells transiently expressing TOLLIP-V5 fusion protein with or without bleomycin treatment. IgG was used as a negative control. Binding of V5-TOLLIP to endogenous LC3 was detected by immunoblot of the immunoprecipitated proteins with an antibody specific for LC3. Immunoblot analysis of LC3A/B II, the LC3 form associated with autophagosome, in cells treated with bleomycin and bafilomycin, alone or in combination as indicated, under TOLLIP overexpression (C) and knocking down (D) conditions are shown. For bleomycin treatment, cells were treated for overnight at 50 μM. For bafilomycin A1 treatment, the cells were treated for 4 hours at 20 μM before harvesting the cells. Representative results from three independent experiments are shown. (E) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of TOLLIP, MAP1LC3A and MAP1LC3B using total RNA isolated from cells overexpressing or knocking down of TOLLIP. Expression levels were normalized to GAPDH. Comparison of expression levels between groups were analyzed by student t-test and *P<0.05.

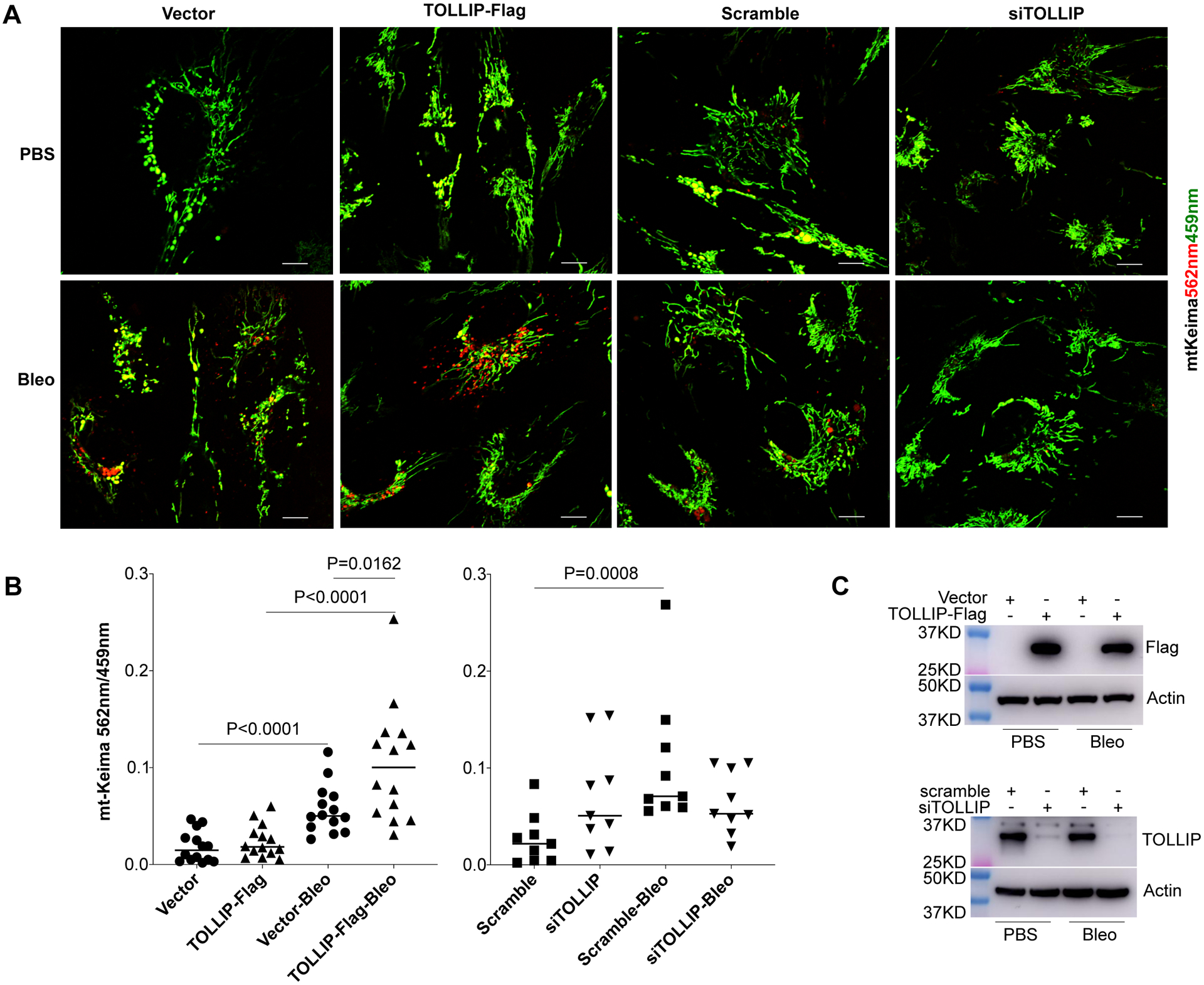

TOLLIP protects BEAS-2B cells from bleomycin induced apoptosis through upregulation of mitophagy

To directly demonstrate that TOLLIP protects BEAS-2B cells from bleomycin induced apoptosis through upregulation of mitophagy, we utilized the mt-Keima live cell imaging reporter system (52). In this system, the coral-derived protein Keima is targeted to the mitochondrial matrix that allows a direct visualization of mitochondria as Green fluorescence in basal condition (at PH 8.0) and as Red fluorescence in acidic environment when damaged mitochondria are fused with lysosome. It has been widely used in studies for monitoring mitophagy in live cells in vitro (52–56). As shown in Figure 6B, bleomycin induced mitophagy in both TOLLIP overexpressing and vector control cells. Significantly higher levels of mitophagy were induced in TOLLIP overexpressing cells than vector control cells (4.3-fold vs 3.1-fold). Similarly, bleomycin increased mitophagy in scramble siRNA cells (4.0-fold) but did not change the level of mitophagy in TOLLIP siRNA treated cells. Therefore, the results of live-cell imaging further support that TOLLIP protects BEAS-2B cells from bleomycin induced apoptosis through upregulation of mitophagy.

Figure 6. TOLLIP facilitates the clearance of damaged mitochondria induced by bleomycin injury.

(A) Representative live cell images (size bar = 100 micron) of bleomycin treated BEAS-2B mt-Keima reporter cells over-expressing TOLLIP, vector control, scramble siRNA, or TOLLIP siRNA. In the mt-Keima cells, the coral-derived protein Keima is targeted to the mitochondrial matrix with Green fluorescence (459 nm) in basal condition (at PH 8.0) and with Red fluorescence (562 nm) in acidic environment when damaged mitochondria are fused with lysosome. A total of 14 and 9 independent fields were imaged for the overexpression experiments and siRNA knockdown experiments, respectively. Results from one representative experiment of three independent experiments are shown. The ratio of Red/Green fluorescence signals was used to quantify mitophagy and shown in (B). P values were calculated using non-parametric Mann-Whitney t-test to compare differences between groups with or without bleomycin treatment. The levels of exogenous TOLLIP protein expression and knocking down of endogenous TOLLIP protein were analyzed using immunoblot shown in (C).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that TOLLIP expression was lower in total RNA and marginally reduced in protein lysates of IPF lungs compared to control lungs. Lung cells expressing high levels of TOLLIP gene included macrophages, alveolar type II and basal cells. TOLLIP protein was expressed in epithelial cells of distal fibrotic regions in IPF lungs. We demonstrated that TOLLIP protected bronchial epithelial cells from bleomycin induced apoptosis by reducing mitochondrial ROS levels and by up-regulating autophagy using primary bronchial epithelial cells and BEAS-2B cells. Therefore, down-regulation of TOLLIP in normal lung epithelial cells may predispose them to injury-induced apoptosis and subsequently contribute to the development of IPF.

IPF has classically been considered to be a disease that arises from the distal airspace. Several recent lines of evidence suggest that the bronchial epithelium does contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of IPF (57–59). One of these is the association of a promoter variant in the airway gene MUC5B with IPF (16, 17, 20). MUC5B is expressed in the fibrotic regions of IPF lungs (17, 46). Overexpression of Muc5b in mice results in worse bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis while knocking down leads to increased mortality due to overwhelming infection (17, 46, 60, 61). The identification of “aberrant basaloid cell” as a potential cell type expressing TOLLIP in fibrotic lung suggests that bronchial epithelial cells may be a relevant cell model for studying TOLLIP function (6, 31). Therefore, we decided to pursue airway epithelial cells as a model system. It is possible that in early disease stage, TOLLIP acts as a protector for insult induced apoptosis. Conversely in epithelial cells within the dense fibrotic region, TOLLIP works as a negative disease player by promoting their survival.

The cytoprotective effect of TOLLIP was observed in the mouse alveolar epithelial MLE12 cells but not in the human fetal alveolar epithelial cells. However, fetal alveolar epithelial cells may not fully recapitulate the matured alveolar epithelial cells since the human lung continues to develop up to two years after birth (62). Comprehensive analysis of TOLLIP expression in different cell lineages from control and fibrotic lungs and cell lineage-specific TOLLIP knockout mice will further explicate the cell type specific roles of TOLLIP in fibrosis.

Although TOLLIP protein expression is marginally lower in total protein lysate of lung parenchyma from IPF patients, it is expressed in the atypical epithelial cells in the distal fibrotic area. The lung epithelium is critical for maintenance of the proper gas exchange surface in normal lung. But in IPF repetitive injury leads to alveolar epithelial cell necrosis, necroptosis, and apoptosis (4, 36, 63–65). Aberrant epithelial cell repair (43–45) is associated with “bronchiolization” of the distal lung in IPF (46–49). In addition to atypical cuboidal hyperplastic alveolar type II cells, cells expressing the markers of proximal airway epithelial cells including goblet cells, basal cells, and ciliated cells are also present in the distal IPF lung (6, 46). Similar to the whole lung single cell RNA sequencing study used in this study, single cell RNA sequencing of purified epithelial cells from both control and IPF lungs (GEO Accession GSE86618 and GSE94555) (6) also showed TOLLIP gene expression in basal, indeterminate, club/goblet cells and alveolar type II cells. Since TOLLIP protected primary bronchial epithelial cells from bleomycin-induced apoptosis, it is plausible that lower expression of TOLLIP in IPF lungs may contribute to apoptosis-vulnerable epithelium at the wavefront of the disease.

Mitochondrial damage leads to mitochondrial ROS accumulation (66). Abnormal mitochondrial structure is one of the cellular features of IPF lung epithelial cells (67). In this study, we demonstrated that TOLLIP reduced mitochondrial ROS accumulation in BEAS-2B cells induced by bleomycin. However, in bone marrow-derived macrophages, TOLLIP knockout reduced low-dose LPS induced ROS level (68). This discrepancy could be due to the nature of ROS accumulation since low dose LPS only induces very low level of ROS which serves as a signaling molecule, while in our study bleomycin induces mitochondrial damage, which leads to higher level ROS accumulation. Damaged mitochondria are either cleared by mitophagy through autophagosome formation or lead to programmed cell death, apoptosis. The fine balance between autophagy and apoptosis controls the fate of both cells and cellular organelles (69). The most common form of mitophagy is mediated by PTEN induced kinase 1 (PINK1), a mitochondrial serine/threonine-protein kinase (70), which accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane and phosphorylates its substrates including parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (PARKIN) (70). Phosphorylated PARKIN exerts its E3 ubiquitin ligase function and ubiquitinates targeted proteins on mitochondrial surface which, in turn, mediates autophagosome formation (71). TOLLIP binds to ubiquitinated proteins through its coupling of ubiquitin to ER degradation (CUE)-domain. It is a critical adaptor protein in selective ubiquitin dependent autophagy pathway by recognizing ubiquitinated cargos such as protein aggregates or organelles (27). TOLLIP has been reported to be associated with PINK1 when both proteins were overexpressed in a cell model (72). However, we did not detect association of endogenous PINK1 with TOLLIP using immunoprecipitation (data not shown). The study by Lazarou et. al. also showed that TOLLIP is not an adaptor protein in PINK1-PARKIN dependent mitophagy (53). Interestingly, TOLLIP was observed in the mitochondrial fraction of lung epithelial cells (data not shown). Therefore, whether TOLLIP facilitates mitophagy through direct association with mitochondrial membrane or association with ubiquitinated proteins on the mitochondrial membrane remains unknown.

LC3 is an important player in autophagosome formation and physically associated with the autophagosome (53). TOLLIP has been reported to be critical in endosome-lysosome fusion in macrophage (73). In consistent with our finding that knocking down TOLLIP was associated with decreased LC3 A/B II levels in bleomycin treated lung epithelial cells, a recent study by Shah et. al. demonstrated that knocking out TOLLIP abolished increased LC3 II levels in THP1 cells after starvation (74). Since TOLLIP is associated with LC3 in lung epithelial cells, it is possible that it interacts with LC3 on the surface of autophagosome and facilitate autophagosome fusion with lysosome. Alternatively, TOLLIP may be involved in the LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP), a distinct pathway of clearing damaged organelles (75). Additionally, TOLLIP may also facilitate the clearance of damaged mitochondria through LC3-indepdendent mitophagy pathway such as vesicular transport to lysosome and unfolded protein response through protease (76). This is the first study showing that TOLLIP may be involved in damaged mitochondria clearance. Our study suggests that TOLLIP may be a homeostasis keeper that attenuated mitochondrial ROS accumulation by clearing damaged mitochondria through enhancing mitophagy in lung epithelial cells.

There are some limitations of this study. First, mechanistic analyses of TOLLIP protective function were derived from in vitro experiments. Future studies with epithelial cell-specific knockout of Tollip or transgenic animal models are needed to validate our findings in vivo. Second, the single cell sequencing data supports that TOLLIP expressing epithelial cells in the distal fibrotic lungs are likely aberrant basaloid cells. However, we did not confirm this using immunostaining with markers specific for the aberrant cells. Future studies are warranted to fully characterize the protein expression profile of these cells. Third, this study mainly focuses on both primary bronchial epithelial and BEAS-2B cells. Studies using alveolar epithelial cells will provide insight to whether TOLLIP also protects these cells from injury induced apoptosis through the same molecular mechanisms as in the bronchial epithelial cells. Fourth, although we have identified the roles of TOLLIP in reducing ROS accumulation and facilitating autophagosome formation and degradation, there could be additional molecular processes associated with its anti-apoptosis function. Fifth, the association of TOLLIP SNPs with susceptibility and outcomes in IPF points to the potential importance of genetics in TOLLIP function. A comprehensive study dissecting the genetic effects in its anti-apoptosis function is needed.

In summary, to our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the molecular function of TOLLIP in the context of IPF and in bleomycin induced lung epithelial cell injury. Future studies on exact molecular involvements of TOLLIP in mitophagy, autophagosome formation, autophagosome and lysosome fusion, and other alternative autophagy pathways are needed. Understanding TOLLIP function and its roles in pathways important for fibrosis development will provide insight to the development of IPF and may lead to novel therapeutic target to treat this devastating disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lea Chwilka, Mark Roth, Yanxia Chu and Mark Ross for technical support. We thank the staffs at the Human Airway Cells and Assays Core of the University of Pittsburgh and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation RDP grant support for human bronchial epithelial cells and lung tissues. We acknowledge the Center for Organ Recovery & Education (CORE) as well as organ donors and their families for the generous gift of tissues used in this study.

Disclosures:

Dr. Kass reports research funding from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals in Pulmonary Hypertension and from Boehringer-Ingelheim, which is unrelated to this manuscript. Dr. Lafyatis has received consulting fees from PRISM Biolab, Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Biocon, Formation, Genentech/Roche, UCB, and Sanofi and grant support from Elpidera and Regeneron, not related to the submitted work. Dr. Rojas reports funding from Regeneron and MedImmune, unrelated to this work.

Support Statement:

This project was supported in part by the Dorothy P. and Richard P. Simmons Center for Interstitial Lung Disease, the Violet Rippy Research Fund, and a Young Investigator Grant from the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (YZ).

ABBREVIATIONS:

- TOLLIP

Toll interacting protein

- IPF

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- MUC5B

mucin 5B

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TGF-β

transformation growth factor- β

- TOM1

target of Myb1 membrane trafficking protein

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- ATG8

Autophagy related protein 8

- LC3

Microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3

- HBE

Human bronchial epithelial cells

- TUNEL assay

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling assay

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- PINK1

PTEN induced kinase 1

- PARKIN

parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase

- CUE domain

coupling of ubiquitin to ER degradation domain

- MARCO

macrophage receptor with collagenous structure

- EPCAM

epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- SFTPC

surfactant protein C

- SFTPA1

surfactant protein A1

- SFTPA2

surfactant protein A2

- ABCA3

ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily A Member 3

Uncategorized References

- 1.King TE Jr., Schwarz MI, Brown K, Tooze JA, Colby TV, Waldron JA Jr., Flint A, Thurlbeck W, and Cherniack RM (2001) Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: relationship between histopathologic features and mortality. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 164, 1025–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thannickal VJ, and Horowitz JC (2006) Evolving concepts of apoptosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 3, 350–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selman M, and Pardo A (2003) The epithelial/fibroblastic pathway in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 29, S93–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selman M, and Pardo A (2006) Role of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from innocent targets to serial killers. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 3, 364–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasse A, Binder H, Schupp JC, Kayser G, Bargagli E, Jaeger B, Hess M, Rittinghausen S, Vuga L, Lynn H, Violette S, Jung B, Quast K, Vanaudenaerde B, Xu Y, Hohlfeld JM, Krug N, Herazo-Maya JD, Rottoli P, Wuyts WA, and Kaminski N (2019) BAL Cell Gene Expression Is Indicative of Outcome and Airway Basal Cell Involvement in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 199, 622–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Y, Mizuno T, Sridharan A, Du Y, Guo M, Tang J, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Perl AT, Funari VA, Gokey JJ, Stripp BR, and Whitsett JA (2016) Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies diverse roles of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JCI insight 1, e90558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan T, Volckaert T, Redente EF, Hopkins S, Klinkhammer K, Wasnick R, Chao CM, Yuan J, Zhang JS, Yao C, Majka S, Stripp BR, Gunther A, Riches DWH, Bellusci S, Thannickal VJ, and De Langhe SP (2019) FGF10-FGFR2B Signaling Generates Basal Cells and Drives Alveolar Epithelial Regeneration by Bronchial Epithelial Stem Cells after Lung Injury. Stem Cell Reports 12, 1041–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seibold MA, Smith RW, Urbanek C, Groshong SD, Cosgrove GP, Brown KK, Schwarz MI, Schwartz DA, and Reynolds SD (2013) The idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis honeycomb cyst contains a mucocilary pseudostratified epithelium. PloS one 8, e58658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alder JK, Stanley SE, Wagner CL, Hamilton M, Hanumanthu VS, and Armanios M (2015) Exome sequencing identifies mutant TINF2 in a family with pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 147, 1361–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alder JK, Chen JJ, Lancaster L, Danoff S, Su SC, Cogan JD, Vulto I, Xie M, Qi X, Tuder RM, Phillips JA 3rd, Lansdorp PM, Loyd JE, and Armanios MY (2008) Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 13051–13056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, Alder JK, Ingersoll RG, Markin C, Lawson WE, Xie M, Vulto I, Phillips JA 3rd, Lansdorp PM, Greider CW, and Loyd JE (2007) Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine 356, 1317–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuart BD, Choi J, Zaidi S, Xing C, Holohan B, Chen R, Choi M, Dharwadkar P, Torres F, Girod CE, Weissler J, Fitzgerald J, Kershaw C, Klesney-Tait J, Mageto Y, Shay JW, Ji W, Bilguvar K, Mane S, Lifton RP, and Garcia CK (2015) Exome sequencing links mutations in PARN and RTEL1 with familial pulmonary fibrosis and telomere shortening. Nature genetics 47, 512–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Kuan PJ, Xing C, Cronkhite JT, Torres F, Rosenblatt RL, DiMaio JM, Kinch LN, Grishin NV, and Garcia CK (2009) Genetic defects in surfactant protein A2 are associated with pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer. American journal of human genetics 84, 52–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronkhite JT, Xing C, Raghu G, Chin KM, Torres F, Rosenblatt RL, and Garcia CK (2008) Telomere shortening in familial and sporadic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 178, 729–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanagihara T, Sato S, Upagupta C, and Kolb M (2019) What have we learned from basic science studies on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society 28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Noth I, Garcia JG, and Kaminski N (2011) A variant in the promoter of MUC5B and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine 364, 1576–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seibold MA, Wise AL, Speer MC, Steele MP, Brown KK, Loyd JE, Fingerlin TE, Zhang W, Gudmundsson G, Groshong SD, Evans CM, Garantziotis S, Adler KB, Dickey BF, du Bois RM, Yang IV, Herron A, Kervitsky D, Talbert JL, Markin C, Park J, Crews AL, Slifer SH, Auerbach S, Roy MG, Lin J, Hennessy CE, Schwarz MI, and Schwartz DA (2011) A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine 364, 1503–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peljto AL, Zhang Y, Fingerlin TE, Ma SF, Garcia JG, Richards TJ, Silveira LJ, Lindell KO, Steele MP, Loyd JE, Gibson KF, Seibold MA, Brown KK, Talbert JL, Markin C, Kossen K, Seiwert SD, Murphy E, Noth I, Schwarz MI, Kaminski N, and Schwartz DA (2013) Association between the MUC5B promoter polymorphism and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Jama 309, 2232–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noth I, Zhang Y, Ma SF, Flores C, Barber M, Huang Y, Broderick SM, Wade MS, Hysi P, Scuirba J, Richards TJ, Juan-Guardela BM, Vij R, Han MK, Martinez FJ, Kossen K, Seiwert SD, Christie JD, Nicolae D, Kaminski N, and Garcia JGN (2013) Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: a genome-wide association study. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 1, 309–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fingerlin TE, Murphy E, Zhang W, Peljto AL, Brown KK, Steele MP, Loyd JE, Cosgrove GP, Lynch D, Groshong S, Collard HR, Wolters PJ, Bradford WZ, Kossen K, Seiwert SD, du Bois RM, Garcia CK, Devine MS, Gudmundsson G, Isaksson HJ, Kaminski N, Zhang Y, Gibson KF, Lancaster LH, Cogan JD, Mason WR, Maher TM, Molyneaux PL, Wells AU, Moffatt MF, Selman M, Pardo A, Kim DS, Crapo JD, Make BJ, Regan EA, Walek DS, Daniel JJ, Kamatani Y, Zelenika D, Smith K, McKean D, Pedersen BS, Talbert J, Kidd RN, Markin CR, Beckman KB, Lathrop M, Schwarz MI, and Schwartz DA (2013) Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nature genetics 45, 613–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore C, Blumhagen RZ, Yang IV, Walts A, Powers J, Walker T, Bishop M, Russell P, Vestal B, Cardwell J, Markin CR, Mathai SK, Schwarz MI, Steele MP, Lee J, Brown KK, Loyd JE, Crapo JD, Silverman EK, Cho MH, James JA, Guthridge JM, Cogan JD, Kropski JA, Swigris JJ, Bair C, Kim DS, Ji W, Kim H, Song JW, Maier LA, Pacheco KA, Hirani N, Poon AS, Li F, Jenkins RG, Braybrooke R, Saini G, Maher TM, Molyneaux PL, Saunders P, Zhang Y, Gibson KF, Kass DJ, Rojas M, Sembrat J, Wolters PJ, Collard HR, Sundy JS, O’Riordan T, Strek ME, Noth I, Ma SF, Porteous MK, Kreider ME, Patel NB, Inoue Y, Hirose M, Arai T, Akagawa S, Eickelberg O, Fernandez IE, Behr J, Mogulkoc N, Corte TJ, Glaspole I, Tomassetti S, Ravaglia C, Poletti V, Crestani B, Borie R, Kannengiesser C, Parfrey H, Fiddler C, Rassl D, Molina-Molina M, Machahua C, Worboys AM, Gudmundsson G, Isaksson HJ, Lederer DJ, Podolanczuk AJ, Montesi SB, Bendstrup E, Danchel V, Selman M, Pardo A, Henry MT, Keane MP, Doran P, Vasakova M, Sterclova M, Ryerson CJ, Wilcox PG, Okamoto T, Furusawa H, Miyazaki Y, Laurent G, Baltic S, Prele C, Moodley Y, Shea BS, Ohta K, Suzukawa M, Narumoto O, Nathan SD, Venuto DC, Woldehanna ML, Kokturk N, de Andrade JA, Luckhardt T, Kulkarni T, Bonella F, Donnelly SC, McElroy A, Armstong ME, Aranda A, Carbone RG, Puppo F, Beckman KB, Nickerson DA, Fingerlin TE, and Schwartz DA (2019) Resequencing Study Confirms That Host Defense and Cell Senescence Gene Variants Contribute to the Risk of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 200, 199–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brissoni B, Agostini L, Kropf M, Martinon F, Swoboda V, Lippens S, Everett H, Aebi N, Janssens S, Meylan E, Felberbaum-Corti M, Hirling H, Gruenberg J, Tschopp J, and Burns K (2006) Intracellular trafficking of interleukin-1 receptor I requires Tollip. Current biology : CB 16, 2265–2270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang G, and Ghosh S (2002) Negative regulation of toll-like receptor-mediated signaling by Tollip. The Journal of biological chemistry 277, 7059–7065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu L, Wang L, Luo X, Zhang Y, Ding Q, Jiang X, Wang X, Pan Y, and Chen Y (2012) Tollip, an intracellular trafficking protein, is a novel modulator of the transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry 287, 39653–39663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keskitalo S, Haapaniemi EM, Glumoff V, Liu X, Lehtinen V, Fogarty C, Rajala H, Chiang SC, Mustjoki S, Kovanen P, Lohi J, Bryceson YT, Seppanen M, Kere J, Heiskanen K, and Varjosalo M (2019) Dominant TOM1 mutation associated with combined immunodeficiency and autoimmune disease. NPJ Genom Med 4, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukherjee S, and Biswas T (2014) Activation of TOLLIP by porin prevents TLR2-associated IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells. Cell Signal 26, 2674–2682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu K, Psakhye I, and Jentsch S (2014) A new class of ubiquitin-Atg8 receptors involved in selective autophagy and polyQ protein clearance. Autophagy 10, 2381–2382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devor DC, Bridges RJ, and Pilewski JM (2000) Pharmacological modulation of ion transport across wild-type and DeltaF508 CFTR-expressing human bronchial epithelia. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 279, C461–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards TJ, Park C, Chen Y, Gibson KF, Peter Di Y, Pardo A, Watkins SC, Choi AM, Selman M, Pilewski J, Kaminski N, and Zhang Y (2012) Allele-specific transactivation of matrix metalloproteinase 7 by FOXA2 and correlation with plasma levels in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302, L746–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, and Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9, 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morse C, Tabib T, Sembrat J, Buschur KL, Bittar HT, Valenzi E, Jiang Y, Kass DJ, Gibson K, Chen W, Mora A, Benos PV, Rojas M, and Lafyatis R (2019) Proliferating SPP1/MERTK-expressing macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The European respiratory journal 54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kusko RL, Brothers JF 2nd, Tedrow J, Pandit K, Huleihel L, Perdomo C, Liu G, Juan-Guardela B, Kass D, Zhang S, Lenburg M, Martinez F, Quackenbush J, Sciurba F, Limper A, Geraci M, Yang I, Schwartz DA, Beane J, Spira A, and Kaminski N (2016) Integrated Genomics Reveals Convergent Transcriptomic Networks Underlying Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 194, 948–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonough JE, Kaminski N, Thienpont B, Hogg JC, Vanaudenaerde BM, and Wuyts WA (2019) Gene correlation network analysis to identify regulatory factors in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 74, 132–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maillard MH, Bega H, Uhlig HH, Barnich N, Grandjean T, Chamaillard M, Michetti P, and Velin D (2014) Toll-interacting protein modulates colitis susceptibility in mice. Inflammatory bowel diseases 20, 660–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jablonski RP, Kim SJ, Cheresh P, Williams DB, Morales-Nebreda L, Cheng Y, Yeldandi A, Bhorade S, Pardo A, Selman M, Ridge K, Gius D, Budinger GRS, and Kamp DW (2017) SIRT3 deficiency promotes lung fibrosis by augmenting alveolar epithelial cell mitochondrial DNA damage and apoptosis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 31, 2520–2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JM, Yoshida M, Kim MS, Lee JH, Baek AR, Jang AS, Kim DJ, Minagawa S, Chin SS, Park CS, Kuwano K, Park SW, and Araya J (2018) Involvement of Alveolar Epithelial Cell Necroptosis in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Pathogenesis. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 59, 215–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee VY, Schroedl C, Brunelle JK, Buccellato LJ, Akinci OI, Kaneto H, Snyder C, Eisenbart J, Budinger GR, and Chandel NS (2005) Bleomycin induces alveolar epithelial cell death through JNK-dependent activation of the mitochondrial death pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289, L521–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang J, Zhang Y, Xie T, Liu N, Chen H, Geng Y, Kurkciyan A, Mena JM, Stripp BR, Jiang D, and Noble PW (2016) Hyaluronan and TLR4 promote surfactant-protein-C-positive alveolar progenitor cell renewal and prevent severe pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Nature medicine 22, 1285–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An CH, Wang XM, Lam HC, Ifedigbo E, Washko GR, Ryter SW, and Choi AM (2012) TLR4 deficiency promotes autophagy during cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303, L748–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slebos DJ, Ryter SW, van der Toorn M, Liu F, Guo F, Baty CJ, Karlsson JM, Watkins SC, Kim HP, Wang X, Lee JS, Postma DS, Kauffman HF, and Choi AM (2007) Mitochondrial localization and function of heme oxygenase-1 in cigarette smoke-induced cell death. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 36, 409–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Tan HW, Liang ZL, Yao Y, Wu DD, Mo HY, Gu J, Chiu JF, Xu YM, and Lau ATY (2019) Lasting DNA Damage and Aberrant DNA Repair Gene Expression Profile Are Associated with Post-Chronic Cadmium Exposure in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Cells 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka A, Jin Y, Lee SJ, Zhang M, Kim HP, Stolz DB, Ryter SW, and Choi AM (2012) Hyperoxia-induced LC3B interacts with the Fas apoptotic pathway in epithelial cell death. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 46, 507–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sisson TH, Mendez M, Choi K, Subbotina N, Courey A, Cunningham A, Dave A, Engelhardt JF, Liu X, White ES, Thannickal VJ, Moore BB, Christensen PJ, and Simon RH (2010) Targeted injury of type II alveolar epithelial cells induces pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 181, 254–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumgartner KB, Samet JM, Stidley CA, Colby TV, and Waldron JA (1997) Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 155, 242–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lawson WE, Crossno PF, Polosukhin VV, Roldan J, Cheng DS, Lane KB, Blackwell TR, Xu C, Markin C, Ware LB, Miller GG, Loyd JE, and Blackwell TS (2008) Endoplasmic reticulum stress in alveolar epithelial cells is prominent in IPF: association with altered surfactant protein processing and herpesvirus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294, L1119–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plantier L, Crestani B, Wert SE, Dehoux M, Zweytick B, Guenther A, and Whitsett JA (2011) Ectopic respiratory epithelial cell differentiation in bronchiolised distal airspaces in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 66, 651–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chilosi M, Poletti V, Murer B, Lestani M, Cancellieri A, Montagna L, Piccoli P, Cangi G, Semenzato G, and Doglioni C (2002) Abnormal re-epithelialization and lung remodeling in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the role of deltaN-p63. Lab Invest 82, 1335–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitsett JA (2018) Airway Epithelial Differentiation and Mucociliary Clearance. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 15, S143–S148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kasper M, and Haroske G (1996) Alterations in the alveolar epithelium after injury leading to pulmonary fibrosis. Histology and histopathology 11, 463–483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Djavaheri-Mergny M, Maiuri MC, and Kroemer G (2010) Cross talk between apoptosis and autophagy by caspase-mediated cleavage of Beclin 1. Oncogene 29, 1717–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mukhopadhyay S, Panda PK, Sinha N, Das DN, and Bhutia SK (2014) Autophagy and apoptosis: where do they meet? Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death 19, 555–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun N, Malide D, Liu J, Rovira II, Combs CA, and Finkel T (2017) A fluorescence-based imaging method to measure in vitro and in vivo mitophagy using mt-Keima. Nat Protoc 12, 1576–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lazarou M, Sliter DA, Kane LA, Sarraf SA, Wang C, Burman JL, Sideris DP, Fogel AI, and Youle RJ (2015) The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature 524, 309–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katayama H, Kogure T, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, and Miyawaki A (2011) A sensitive and quantitative technique for detecting autophagic events based on lysosomal delivery. Chem Biol 18, 1042–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fang EF, Kassahun H, Croteau DL, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Marosi K, Lu H, Shamanna RA, Kalyanasundaram S, Bollineni RC, Wilson MA, Iser WB, Wollman BN, Morevati M, Li J, Kerr JS, Lu Q, Waltz TB, Tian J, Sinclair DA, Mattson MP, Nilsen H, and Bohr VA (2016) NAD(+) Replenishment Improves Lifespan and Healthspan in Ataxia Telangiectasia Models via Mitophagy and DNA Repair. Cell Metab 24, 566–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bingol B, Tea JS, Phu L, Reichelt M, Bakalarski CE, Song Q, Foreman O, Kirkpatrick DS, and Sheng M (2014) The mitochondrial deubiquitinase USP30 opposes parkin-mediated mitophagy. Nature 510, 370–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jenkins G (2018) A big beautiful wall against infection. Thorax 73, 485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Evans CM, Fingerlin TE, Schwarz MI, Lynch D, Kurche J, Warg L, Yang IV, and Schwartz DA (2016) Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Genetic Disease That Involves Mucociliary Dysfunction of the Peripheral Airways. Physiological reviews 96, 1567–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwartz DA (2018) Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Is a Genetic Disease Involving Mucus and the Peripheral Airways. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 15, S192–S197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hancock LA, Hennessy CE, Solomon GM, Dobrinskikh E, Estrella A, Hara N, Hill DB, Kissner WJ, Markovetz MR, Grove Villalon DE, Voss ME, Tearney GJ, Carroll KS, Shi Y, Schwarz MI, Thelin WR, Rowe SM, Yang IV, Evans CM, and Schwartz DA (2018) Muc5b overexpression causes mucociliary dysfunction and enhances lung fibrosis in mice. Nature communications 9, 5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roy MG, Livraghi-Butrico A, Fletcher AA, McElwee MM, Evans SE, Boerner RM, Alexander SN, Bellinghausen LK, Song AS, Petrova YM, Tuvim MJ, Adachi R, Romo I, Bordt AS, Bowden MG, Sisson JH, Woodruff PG, Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, De la Garza MM, Moghaddam SJ, Karmouty-Quintana H, Blackburn MR, Drouin SM, Davis CW, Terrell KA, Grubb BR, O’Neal WK, Flores SC, Cota-Gomez A, Lozupone CA, Donnelly JM, Watson AM, Hennessy CE, Keith RC, Yang IV, Barthel L, Henson PM, Janssen WJ, Schwartz DA, Boucher RC, Dickey BF, and Evans CM (2014) Muc5b is required for airway defence. Nature 505, 412–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith LJ, McKay KO, van Asperen PP, Selvadurai H, and Fitzgerald DA (2010) Normal development of the lung and premature birth. Paediatric respiratory reviews 11, 135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.King TE Jr., Pardo A, and Selman M (2011) Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 378, 1949–1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Myers JL, and Katzenstein AL (1988) Epithelial necrosis and alveolar collapse in the pathogenesis of usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest 94, 1309–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Myers JL, and Katzenstein AL (1988) Ultrastructural evidence of alveolar epithelial injury in idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia. Am J Pathol 132, 102–109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zorov DB, Filburn CR, Klotz LO, Zweier JL, and Sollott SJ (2000) Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine 192, 1001–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bueno M, Lai YC, Romero Y, Brands J, St Croix CM, Kamga C, Corey C, Herazo-Maya JD, Sembrat J, Lee JS, Duncan SR, Rojas M, Shiva S, Chu CT, and Mora AL (2015) PINK1 deficiency impairs mitochondrial homeostasis and promotes lung fibrosis. The Journal of clinical investigation 125, 521–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maitra U, Deng H, Glaros T, Baker B, Capelluto DG, Li Z, and Li L (2012) Molecular mechanisms responsible for the selective and low-grade induction of proinflammatory mediators in murine macrophages by lipopolysaccharide. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 189, 1014–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marino G, Niso-Santano M, Baehrecke EH, and Kroemer G (2014) Self-consumption: the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 15, 81–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koyano F, Okatsu K, Kosako H, Tamura Y, Go E, Kimura M, Kimura Y, Tsuchiya H, Yoshihara H, Hirokawa T, Endo T, Fon EA, Trempe JF, Saeki Y, Tanaka K, and Matsuda N (2014) Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature 510, 162–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sarraf SA, Raman M, Guarani-Pereira V, Sowa ME, Huttlin EL, Gygi SP, and Harper JW (2013) Landscape of the PARKIN-dependent ubiquitylome in response to mitochondrial depolarization. Nature 496, 372–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sekine S (2019) PINK1 import regulation at a crossroad of mitochondrial fate. Journal of biochemistry [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baker B, Geng S, Chen K, Diao N, Yuan R, Xu X, Dougherty S, Stephenson C, Xiong H, Chu HW, and Li L (2015) Alteration of lysosome fusion and low-grade inflammation mediated by super-low-dose endotoxin. The Journal of biological chemistry 290, 6670–6678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shah JA, Emery R, Lee B, Venkatasubramanian S, Simmons JD, Brown M, Hung CF, Prins JM, Verbon A, Hawn TR, and Skerrett SJ (2019) TOLLIP deficiency is associated with increased resistance to Legionella pneumophila pneumonia. Mucosal immunology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martinez J (2018) LAP it up, fuzz ball: a short history of LC3-associated phagocytosis. Current opinion in immunology 55, 54–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ashrafi G, and Schwarz TL (2013) The pathways of mitophagy for quality control and clearance of mitochondria. Cell death and differentiation 20, 31–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.