Abstract

The coronavirus pandemic is one of the most significant public health events in recent history. Currently, no specific treatment is available. Some drugs and cell-based therapy have been tested as alternatives to decrease the disease’s symptoms, length of hospital stay, and mortality. We reported the case of a patient with a severe manifestation of COVID-19 in critical condition who did not respond to the standard procedures used, including six liters of O2 supplementation under a nasal catheter and treatment with dexamethasone and enoxaparin in prophylactic dose. The patient was treated with tocilizumab and an advanced therapy product based on umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (UC-MSC). The combination of tocilizumab and UC-MSC proved to be safe, with no adverse effects, and the results of this case report prove to be a promising alternative in the treatment of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome due to SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: COVID-19, mesenchymal stromal cells, umbilical cord, tocilizumab

Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic is one of the most significant public health events in recent history. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the new coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) 1 , can result in a severe acute respiratory syndrome with significant morbidity and mortality, in addition to significant impacts on health and the economy. Since December 6th, 2020, COVID-19 has affected more than 115 million people, resulting in more than 2.5 million deaths worldwide 2 . Currently, no specific treatment is available. Some drugs and cell-based therapy have been tested as alternatives to decrease the disease’s symptoms, length of hospital stay, and mortality.

Tocilizumab is a US Food and Drug Administration-approved IL-6 receptor antagonist commonly used to treat cytokine release syndrome (CRS) secondary to chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy 3 . The proinflammatory IL-6 appears as one of the critical cytokines leading to the inflammatory storm, resulting in increased alveolar gas exchange dysfunction 4 –6 .

Currently, mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) have been introduced as one of the therapies used to treat COVID-19 disease 7 . These cells secrete bioactive factors that protect and repair damaged tissue, in addition to anti-apoptotic, scar inhibitory, angiogenesis stimulating, and mitogenic effects for intrinsic progenitor cells of the tissue 8 . There is also the secretion of chemoattractive molecules by MSC that can recruit other cell types to repair injured tissue 9,10 .

Material and Methods

According to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki), this study was carried out. Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from local Ethics Committee in Human Research/CONEP (CAAE: 30833820.8.0000.0020, date of approval: 23 May 2020). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying image.

Clinical Presentation

A 51-year-old patient with a previous history of high blood pressure, urethral stenosis, and body mass index of 36.92 presented frontal headache associated with asthenia and myalgia, fever, dry cough, and hypoxia. A positive PCR test for SARS-COV2 confirmed the disease ten days before first cell infusion (D10). Seven days after (D3), there was worsening of asthenia, diarrhea episodes, and the onset of dyspnea, requiring hospitalization. Upon admission (D2), the patient presented tachypnea and 84% O2 saturation (sat O2) in room air, associated with diffuse vesicular murmur with no other changes on physical examination. Laboratory tests showed hyperferritinemia (1.5 ng/mL), lymphopenia (445 lymphocytes/µL), and thrombocytopenia (77.35 × 109/µL), in addition to a slight elevation in the D-dimer (377.5 ng/mL) and chest tomography with focal opacities with a ground-glass aspect, dispersed in both lungs, predominantly on the periphery. Despite the slight improvement after 6 liters of O2 supplementation under a nasal catheter and treatment with dexamethasone and enoxaparin in prophylactic dose, he presented worsening hypoxemia and need to be transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), where he received support with non-invasive mechanical ventilation and an infusion of 400 mg of tocilizumab.

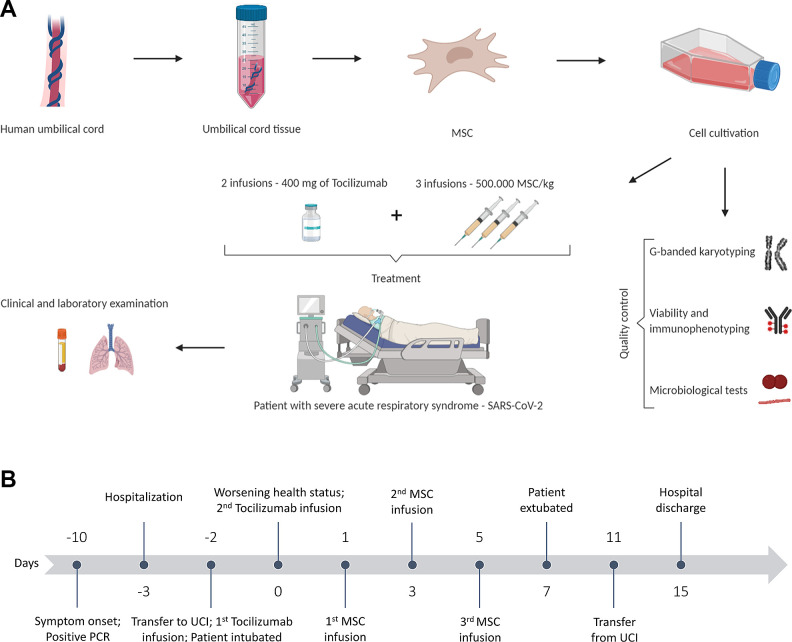

The following day (D1), the patient presented persistent hypoxemia despite O2 supplementation and was submitted to orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, followed by prone position. This maneuver allowed an increase of the PO2/FiO2 ratio from 87 to 190, but the patient presented hemodynamic instability. An angiotomography confirmed a diagnostic hypothesis of pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), and full anticoagulation was started. The patient was then submitted to a new dose of tocilizumab. Ten days after the beginning of symptoms and three days of the worsening of the severity of the clinical condition (D0), the patient was included in a study protocol for treatment with allogeneic umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (UC-MSC) to received three intravenously infusions of 500,000 cells (passage 3) per kilogram in alternate days (Fig. 1A, B). The MSC were diluted in 30 mL of saline supplemented with 20% human albumin and 5% Acid Citrate Dextrose (ACD) and were infused at an interval of five minutes (6 mL / minute).

Fig. 1.

Study design. (A) Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (UC-MSC) were isolated, expanded, and evaluated for surface markers, viability, presence of fungi and bacteria, and chromosomal abnormalities. The patient received three infusions of 500.00 UC-MSCs/kg and two infusions of 400 mg of tocilizumab. The patient’s clinical and laboratory evaluations were performed pre-MSC infusion (D1) and on days 2, 4, 6, 14, 60, and 120. (B) Schematic representation of the days before (minus) and after the first infusion of UC-MSC.

In D1 and D3, the patient received the first and second doses of UC-MSC despite maintaining hemodynamic instability and requiring prone position and high ventilatory parameters, in addition to neuromuscular blockers. Even though a slight improvement was observed, the patient did not withstand a spontaneous ventilation test. He received a third dose of UC-MSC at D5 and was extubated at D7. He uneventfully presented signs and symptoms of critical illness polymioneuropathy, with significant improvement on subsequent days, receiving discharge from the ICU on D11 and hospital discharge on D15, walking normally, with fatigue and dry cough symptoms. Two months after the first UC-MSC infusion, the patient no longer had symptoms related to the disease.

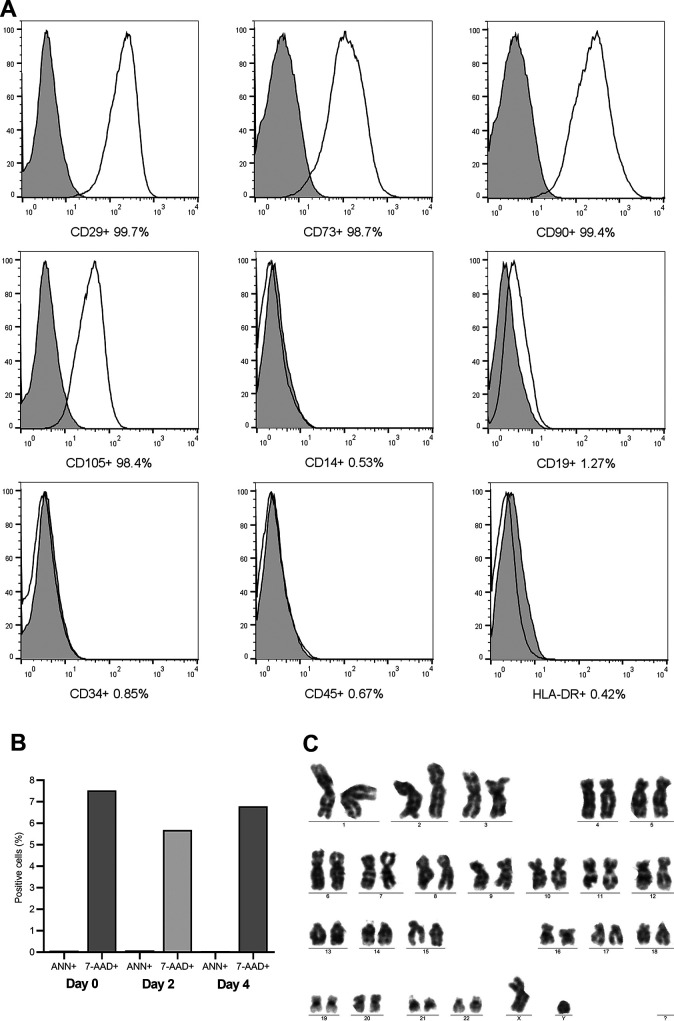

Advanced Therapy Product Manufacturing

Allogeneic MSC were obtained from the umbilical cord of a healthy donor with negative serological tests for infectious agents and negative RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2. The procedure was performed following Good Manufacturing Practices for an Advanced Cell Therapy Product. After the standardized process of mechanical and enzymatic isolation, MSC were expanded in vitro until passage 3 and showed the viability of 97%; negative cultures for bacteria and fungi, absence of endotoxin and Mycoplasma; flow cytometry characterization with positive markings for CD90, CD105, CD29, and CD73 and negative for CD45, CD34, CD14, CD19, and HLA-DR (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA); and absence of clonal chromosomal aberrations in G-banding karyotype analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Quality control of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (UC-MSC). (A) Cell characterization; (B) Cell viability. (C) Cytogenetics test. The cells showed a high expression of CD29, CD73, CD90, and low expression of CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR markers (A). Cell viability analysis showed less than 8% of dead cells (7-AAD) and less than 1% of cells in apoptosis (Annexin-V) (B). The UC-MSC did not show any chromosomal aberrations. Ann: Annexin; 7-AAD: 7-amino actinomycin.

Laboratory Findings

The following parameters were evaluated in the pre-infusion of cells (D0), on the day following each infusion (D2, D4, and D6), on the 14th (D14) and two (D60) and four (D120) months after the first infusion: viral load, immune response (T lymphocytes), C-reactive protein level in plasma, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, total lymphocyte and subpopulation counts (platelets, inflammatory cells, and reticulocytes), TGO/TGP, increased prothrombin time, D-dimer, creatinine, and troponin.

Viral Load Determination

RNA extraction was performed with the QIAamp Viral RNA Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The reverse transcription and quantitative PCR reaction were performed in the same step using GoTaq Probe 1-Step RT-qPCR System (Promega, Madison, WI, EUA) with LightCycler system (Roche, São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil) using the manufacturer’s recommendations and primers RdRP_SARSr- F2 established and validated by Corman and collaborators 11 . The relative quantification of RdRP was calculated about the pre-infusion time of MSCs using ΔΔCq methods.

Immunophenotypic Profile

Immunophenotypic characterization of peripheral blood (PB) lymphocytes was performed with conventional stain-lyse sample preparation techniques according to Kalina et al. 12 Commercial antibodies were used to analyze the expression of cell surface markers CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD38, CD127, CD25, and HLA-DR (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA, USA). FACS CantoII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used for data acquisition and Infinicyttm software (Cytognos, Salamanca, Spain—version 2.0) to flow cytometry analyses.

Image Analysis

Chest computed tomography scan (CT) is the golden standard diagnostic tool for lung diseases and has been used for accessing the severity of the COVID-19. During the evaluation, the lung was divided into six zones (upper, middle, and lower on both sides) by the tracheal carina level and the inferior pulmonary vein level bilaterally on CT using a modified scoring system showed by Li e colaboradores 13 .

Results

Laboratory Findings

Results that lie outside the reference ranges decreased during the follow-up from D0 to D60: creatinine (1.87 to 0.9 mg/dL), TGO (74 to 18 U/L), ferritin (2,611.7 to 206.88 ng/mL), D-dimer (11,400 to 141.27 ng/mL) and C-reactive protein (25.3 to 0.4 mg/mL) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory Findings.

| D0 | D2 | D4 | D6 | D14 | D60 | D120 | Reference Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.87 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.01 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.9 | 0.9 to 1.3 mg/dL |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 57 | 80 | 90 | 93 | 30 | 34 | 30 | 17 to 43 mg/dL |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.3 to 1 mg/dL |

| TGO (U/L) | 74 | 54 | 57 | 56 | 40 | 20 | 18 | < 50 U/L |

| TGP (U/L) | 53 | 49 | 65 | 60 | 92 | 25 | 22 | < 50 U/L |

| LDH (U/L) | 756 | 541 | 490 | 540 | 359 | 150 | 143 | 140 to 271 U/L |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 2,611.7 | 2,006.7 | 2,049 | 2,466 | 1,109.7 | 281.8 | 206.8 | 23.9 a 336.2ng/mL |

| Troponina I (ng/mL) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <0.02 ng/mL |

| Lactate (nmol/L) | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | <1.8 nmol/L |

| C-reactive protein (mg/mL) | 25.3 | 12.0 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | <5.0 mg/mL |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 11.400 | 3,545 | 3.977 | 3,897 | 1,675 | 369.7 | 141.27 | <554.0 ng/mL |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 353 | 267 | 229 | 250 | 197 | 418.39 | 299.9 | 200 to 395 mg/dL |

| KPTT (seconds) | 25.5 | 28.4 | 25.9 | 25.3 | 21.9 | 32.2 | _ | 24.9 a 37 seconds |

D0, pre-Infusion; D2, day after fisrt UC-MSC infusion; D4, day after second UC-MSC infusion; D6, day after third UC-MSC infusion; D14: 14 days after first UC-MSC infusion; D60, 60 days from first UC-MSC infusion; and D120, 120 days from first UC-MSC infusion.

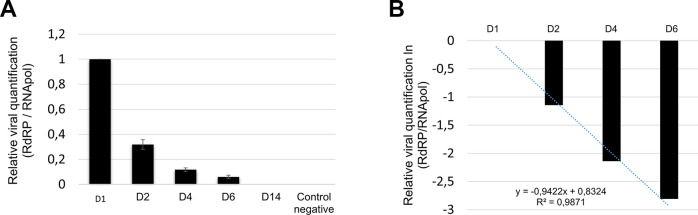

Viral Load Determination

The relative viral quantification decreased gradually from 1 (D0) to 0.06 (D6) RdRP/RNApol, being undetectable in D14 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Relative viral quantification. (A) The viral RrRP gene’s presence was normalized by the human RNApol gene’s presence and decreased gradually from the viral gene in the patient’s samples from 1 (D1) to 0.06 (D6) undetectable in D14. (B) The viral slope (-0.9422) and R2 (0.9871) was established after linearization of the data by natural logarithm (ln(x)) and obtaining the linear equation.

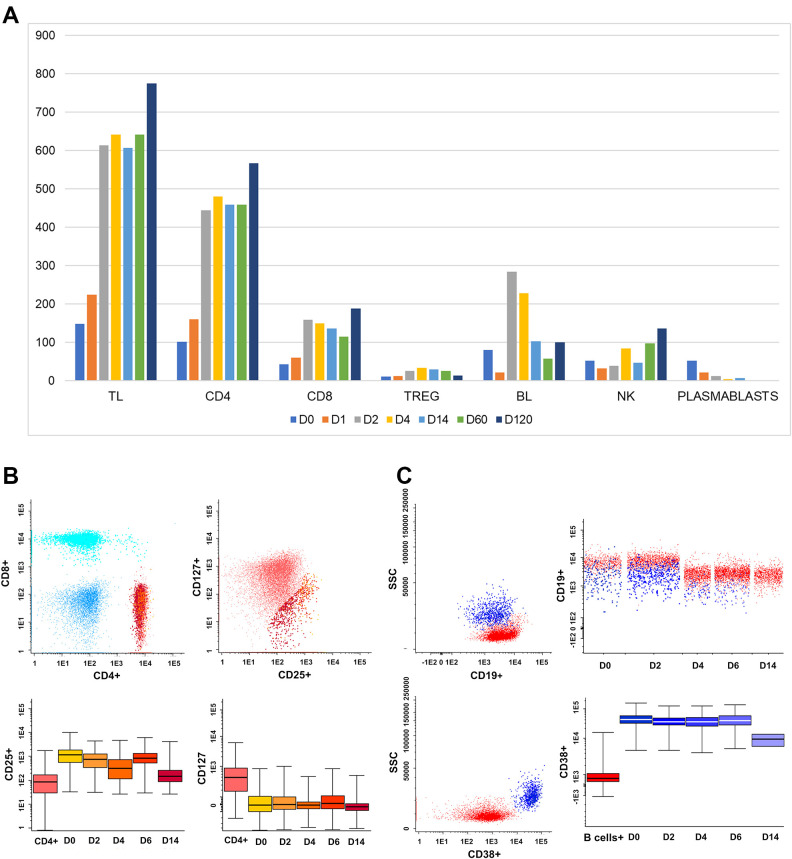

Immunophenotypic Profile

We observed an increase in the absolute number of total lymphocytes, total T-cell subpopulations T helper (CD4), and T regulatory (Treg) cells. Plasmablasts, in contrast, were high compared to average values at the begging of the viral disease, decreasing from 52 (D0) to 0.01(D120) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Immunophenotypic profile. (A) An increase in the absolute number of T lymphocytes/ µL also has been observed to have progressively increased from 148.6 (D0), 642.6 (D6), 607.4 (D14), 485,7(D60), and 775.4 (D120); CD4 T lymphocytes, 102 (D0), 481.2 (D6), 459.5 (D14), 358.0 (D60), and 567.9 (D120) and Treg lymphocytes 10.8 (D0), 34 (D6), 29.8 (D14), 25.9 (D60), and 14.2 (D120). Plasmablasts, in contrast, progressively decreased from 52 (D0) to 0.01 (D120). (B) Lymphocytes gated on CD4 (red/orange) and analyzed in merge form of the sequencing days (D0, D1, D2, D4, D6, and D14), showing the decrease in CD25+/CD127neg T cells—TREG (Orange scale). (C) B-cell lymphocytes gated on CD19 (red) and Plasmablasts gated on CD19+CD38++ (blue scale), showing a decrease in plasmablasts number from D0 to D14. TL (T Lymphocyte); CD4 (cluster of differentiation); TREG (T regulatory cells); BL (B Lymphocyte).

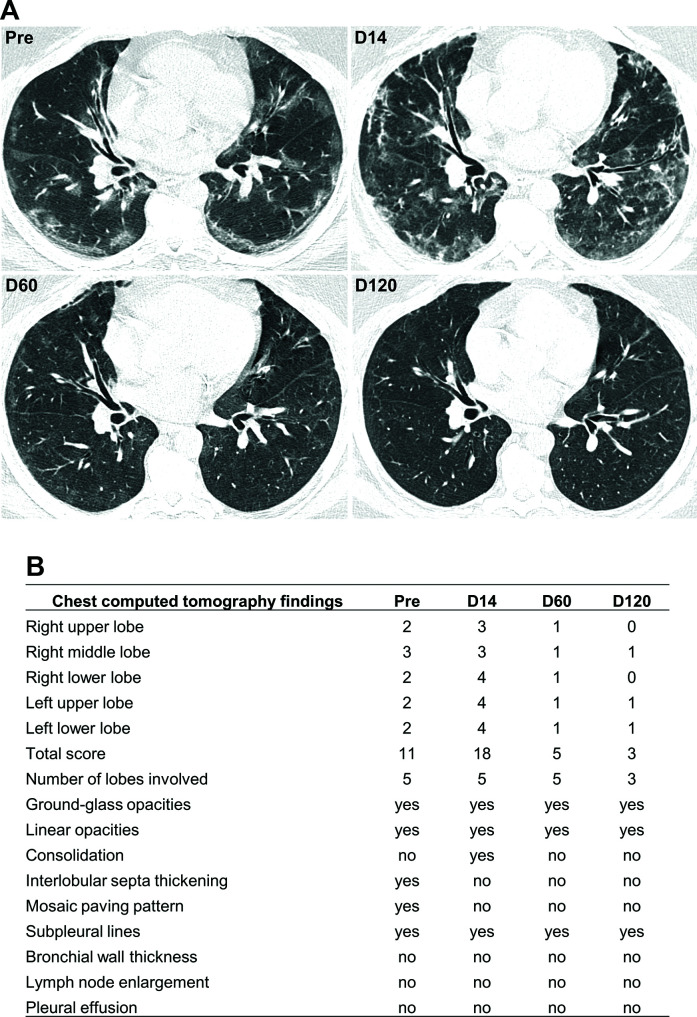

Image Analysis

The CT showed ground-glass opacities associated with crosslinking (mosaic paving) and subpleural lines, predominantly peripheral and basal at the beginning of treatment with an increase in D14. In the evaluation of D60, a marked regression of opacities with practically complete regression in D 120 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Chest computed tomography scan. (A) Chest CT scan without contrast, the axial section at the lower lobes level. Pre-transplantation, showing ground-glass opacities associated with crosslinking (mosaic paving) and subpleural lines, predominantly peripheral and basal. D14 shows an increase in the extent of ground-glass opacities, now with a more significant amount of peribronchovascular opacities. D60 shows marked complete regression of the opacities previously described. D120 shows almost complete regression of the opacities previously described. (B) Each lobe was assigned a score that was based on the following: score 0, 0% involvement; score 1, less than 5% involvement; score 2, 5% to 25% involvement; score 3, 26% to 49% involvement; score 4, 50% to 75% involvement; and score 5, greater than 75% involvement. Scores of 0 to 5 were determined for each lobe, with a total possible score of 25 (adapted from Li et al. 13 ).

Discussion

The mortality for critical and severe cases of patients with COVID-19 reached as high as 60.5% 14 . In this study, a patient with a severe manifestation of COVID-19 in critical condition who did not respond to the standard procedures used was treated with tocilizumab and an advanced therapy product based on UC-MSC.

Xu and colleagues 15 demonstrated that the symptoms, hypoxemia, and CT opacity changes were improved immediately after the treatment with tocilizumab in most patients, suggesting that this monoclonal antibody could be an efficient therapy for the treatment of COVID-19. In the specific case of this report, the patient did not improve after the first administration of tocilizumab, requiring a second administration of the drug, and due to the patient’s critical condition, the infusion of UC-MSC was included in the protocol.

The role of neutralizing antibodies appears to be promising in preventing the worsening of nonhospitalized patients with Covid-19. REGN-COV2 (casirivimab and imdevimab) reduced viral load, with a more significant effect on patients whose immune response had not yet been initiated or had a high viral load at baseline 16 . Similarly, treatment with bamlanivimab and etesevimab, compared with placebo, was associated with a statistically significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2 viral load 17 . Thus, mild or moderate COVID-19 seems to benefit from the use of neutralizing antibodies, but in the most severe cases, the use of this strategy individually does not seem to be efficient. Therefore, the association with another type of treatment, as in this case the MSC infusion, may be the key to increase efficiency.

Multiple ongoing trials have demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of using MSC in treating severe acute respiratory syndrome due to SARS-CoV-2 associated with a significant reduction in serious adverse events, mortality, and time to recovery compared to the control groups 18 –22 . MSC therapy has the capacity of anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory functions, promotes the regeneration of damaged tissues, inhibits tissue fibrosis, and even more, MSC do not have an ACE2 receptor, which make them immune to SARS-CoV-2 23 . MSC-mediated immunosuppression is due to cell-cell contact (essential for its inhibitory function) and the release of soluble factors and requires initial activation of proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-y, TNFα, IL-1α, or IL-1β. In addition to immunosuppression, MSC stimulate the proliferation of regulatory T cells CD4 + and CD25 +, which act in the induction and maintenance of peripheral tolerance 24–25 .

After the two infusions of tocilizumab and, more specifically, from the first infusion of MSC, the patient started to show progressive clinical improvement, which was evidenced by the results of laboratory tests that were approaching the reference levels for a healthy individual. The viral load decreased until it was undetectable at D14. The increase of plasmablasts and activated B-cells is typical in acute viral infections and progressively decreased, demonstrating the patient’s recovery. A study evaluating the first 250,000 cases of hospitalization for COVID-19 in Brazil showed a mortality rate of 55% of patients with RT-qPCR-confirmed COVID-19, younger than 60 years, admitted to the ICU and submitted to mechanical ventilation from February to August 2020 in the southern region 26 . The patient presented in this case study had the same characteristics as the patients mentioned in Ranzani and collaborators’ study, which leads us to assume that the treatment we used effectively preserved the patient’s life.

Further studies with a more significant number of patients may carry the possibility of using tocilizumab combined with UC-MSC. The increase of patients who may need this advanced therapy product requires many readily available cells. Umbilical cord tissue (UCT) has advantages compared to other MSC sources because it is a material that would be disposable, the cells have a higher frequency of proliferation, and can be used allogeneic stem cell infusion 27,28 .

Conclusion

The synergistic combination of an IL-6 receptor antagonist and a cell-based product with anti-inflammatory effects can lead to decreased inflammatory cytokines, increased regulatory cells, and lung repair. The use of tocilizumab and MSC proved to be safe, with no adverse effects, and the results of this case report prove to be a promising alternative in the treatment of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome due to SARS-CoV-2.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the clinical analysis laboratory unit (ULAC) of the Complexo Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná for carrying out the laboratory tests.

Footnotes

Author Contribution: Conceived and designed experiments: ACS, CLKR, AC and PRSB; Performed the experiments: ACS, CLKR, LMBL, DRD, CAL PS, APA, DBM, BS, AM, VRJ, YS and IMV; Performed Clinical Procedures: CLF, JSL, EB and LLR; Contributed analysis tools: ACS, CLKR, PS, APA and AC; Wrote the paper: ACS and CLKR; Edited the paper: ACS and LMBL. ACS and CLKR / AC and PRSB: these authors contributed equally to this work.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from Ethics Committee in Human Research of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR) (CAAE: 30833820.8.0000.0020) and Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa (CONEP).

Statement OF Human Rights: All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the Ethics Committee in Human Research of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR) (CAAE: 30833820.8.0000.0020) approved protocols.

Statement of Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Grants from MS-SCTIE-Decit/CNPq [nº. 443916/2018-7].

ORCID iDs: Alexandra Cristina Senegaglia  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8052-6357

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8052-6357

Lidiane Maria Boldrini-Leite  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9277-5158

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9277-5158

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), If you are at High Risk [internet]. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/specific-groups/high-riskcomplications.html.

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [internet]. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://covid19.who.int/.

- 3. Frey N, Porter D. Cytokine release syndrome with chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(4):123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Conti P, Ronconi G, Caraffa A, Gallenga C, Ross R, Frydas I, Kritas S. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and lung inflammation by Coronavirus-19 (CoV-19 or SARS-CoV-2): anti-inflammatory strategies. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(2):327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, Liu S, Zhao P, Liu H, Zhu L, Tai Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Metcalfe SM. Mesenchymal stem cells and management of COVID-19 pneumonia. Med Drug Discov. 2020;5:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caplan AI, Dennis JE. Mesenchymal stem cells as trophic mediators. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98(5):1076–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Law S, Chaudhuri S. Mesenchymal stem cell and regenerative medicine: regeneration versus immunomodulatory challenges. Am J Stem Cells. 2013;2(1):22–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saldaña L, Bensiamar F, Vallés G, Mancebo FJ, García-Rey E, Vilaboa N. Immunoregulatory potential of mesenchymal stem cells following activation by macrophage-derived soluble factors. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):01–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, Molenkamp R, Meijer A, Chu DK, Bleicker T, Brünink S, Schneider J, Schmidt ML, Mulders DGJC, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3):2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kalina T, Flores-Montero J, van der Velden VHJ, Martin-Ayuso M, Böttcher S, Ritgen M, Almeida J, Lhermitte L, Asnafi V, Mendonça A, Tute R, et al. EuroFlow standardization of flow cytometer instrument settings and immunophenotyping protocols. Leukemia. 2012;26(9):1986–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li K, Wu J, Wu F, Guo D, Chen L, Fang Z, Li C. The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Invest Radiol. 2020;55(6):327–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, Yu T, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Res Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu X, Han M, Li T, Sun W, Wang D, Fu B, Zhou Y, Zheng X, Yang Y, Li X, Zhang X, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(20):10970–10975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, Ali S, Gao H, Bhore R, Musser BJ, Soo Y, Rofail D, Im J, Perry C, et al. Trial investigators. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):238–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, Boscia J, Heller B, Morris J, Huhn G, Cardona J, Mocherla B, Stosor V, Shawa I, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate covid-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(7):632–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lanzoni G, Linetsky E, Correa D, Cayetano SM, Marttos AC, Alvarez RA, Gil AA, Poggioli R, Ruiz P, Hirani K, Bell CA, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for COVID-19 ARDS: A double blind, phase 1/2a, randomized controlled trial. 2020. Available at SSRN: 10.2139/ssrn.3696875. [DOI]

- 19. Yip HK, Fang WF, Li YC, Lee FY, Lee CH, Pei SN, Ma MC, Chen KH, Sung PH, Lee MS. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal. Stem cells for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(5):391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matthay MA, Calfee CS, Zhuo H, Thompson BT, Wilson JG, Levitt JE, Rogers AJ, Gotts JE, Wiener-Kronish JP, Bajwa EK, Donahoe MP, et al. Treatment with allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells for moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (START study): a randomised phase 2a safety trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(2):154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zheng G, Huang L, Tong H, Shu Q, Hu Y, Ge M, Deng K, Zhang L, Zou B, Cheng B, Xu J. Treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome with allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guo Z, Chen Y, Luo X, He X, Zhang Y, Wang J. Administration of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zumla A, Wang FS, Ippolito G, Petrosillo N, Agrati C, Azhar EI, Chang C, El-Kafrawy SA, Osman M, Laurence Zitvogel L, Galle PR, et al. Reducing mortality and morbidity in patients with severe COVID-19 disease by advancing ongoing trials of mesenchymal stromal (stem) Cell (MSC) therapy - achieving global consensus and visibility for cellular host-directed therapies. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blanc KL, Ringdén O. Immunomodulation by mesenchymal stem cells and clinical experience. J Intern Med. 2007;262(5):509–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uccelli A, Pistoia V, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression? Trends Immunol. 2007;28(5):219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ranzani OT, Bastos LSL, Gelli JGM, Marchesi JF, Baião F, Hamacher S, Bozza FA. Characterisation of the first 250000 hospital admissions for COVID-19 in Brazil: a retrospective analysis of nationwide data. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(4):407–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barlow S, Brooke G, Chatterjee K, Price G, Pelekanos R, Rossetti T, Doody M, Venter D, Pain S, Gilshenan K, Atkinson K. Comparison of human placenta- and bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells and Dev. 2008;17(6):1095–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pham PV, Truong NC, Le PTB, Tran TDX, Vu NB, Bui KHT, Phan NK. Isolation and proliferation of umbilical cord tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells for clinical applications. Cell Tissue Bank. 2016;17(2):289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]