Abstract

Recovery homes for individuals with substance use disorders (SUD) called Oxford House (OH) have been shown to improve the prospects of a successful recovery across different sub-populations, and these homes may be particularly beneficial for veterans in recovery. An estimated 18% of OH residents are veterans; however, not much is known about their experiences living in these homes. Participants included 85 veterans and non-veterans living in 13 OHs located in different regions of the United States. Using social network analysis and multi-level modeling, we investigated whether the social networks of veterans residing with other veterans were more cohesive compared to veterans living with only non-veterans. Results indicated that veterans residing with other veterans had stronger relationships with other OH residents compared to veterans that reside with all non-veterans. The implications for theory and practice are discussed. Further research is needed to determine if greater social network cohesion leads to better recovery outcomes for veterans.

Keywords: Veterans, substance use disorders, recovery homes, aftercare, social networks, cohesion, peer support, social identity theory

Introduction

Oxford Houses (OHs; Oxford House, 2008) are the largest group of substance abuse recovery homes in the United States (U.S.), with over 2,000 OHs located throughout the U.S. housing over 20,000 residents (Jason et al., 2007), of which 18% are estimated to be veterans. OHs are self-run recovery homes with no professional staff on-site and no limitations on duration of stay, with occupancy for 6 to 12 people. There is evidence that OHs lead to better recovery outcomes (Jason et al., 2006) across different sub-populations, including individuals with psychiatric comorbidity (Majer, Jason, et al., 2008), and those that were involved with the criminal justice system (Jason, Olson, & Harvey, 2015). Additionally, OHs have lower rates of relapse, lower criminal justice recidivism, and greater employment outcomes compared to traditional recovery homes and other community-based aftercare services (Aase et al., 2009; Jason, Olson, et al., 2007; Jason, Olson, Harvey, 2015), particularly among those that stay in residence for six months or more.

Veterans from Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) have a higher prevalence of substance use disorders (SUD) (Boden & Hoggatt, (2018), Golub, Vazan, Bennett, & Liberty, 2013 Hoggatt, Lehavot, Krenek, Schweizer, & Simpson (2017); Kelsall et al., 2015), psychiatric and substance abuse comorbidity (Allen, Crawford, & Kudler, 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2007; Seal et al. (2011), and homelessness (Tsai, Link, Rosenheck, & Pietrzak, 2016; Fargo et al., 2012) than other comparable segments of the U.S. population. Despite the high rates of SUDs, treatment rates among veterans with a SUD is low, and rates of relapse and treatment discontinuation are high among veterans that utilize the Veterans Affairs healthcare systems and those that utilize non-VA healthcare providers (Boden & Hoggatt, 2018; Erbes, Westermeyer, Engdahl, & Johnson, 2007; Decker, Peglow, Samples, & Cunningham, 2017; Golub et al. 2013; Kraemer et al. 2019; Lan et al., 2016; Larson, Wooten, Adams, & Merrick, 2012; Laudet, Timko, & Hill, 2014). In a nationally representative sample of veterans, 17.1% had a SUD, of which only 28.7% received treatment in the past year (Boden & Hoggatt, 2018). The 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health revealed that 26.7% of veterans had a SUD, of which only 10.6% received a SUD treatment. A study examining outcomes among veterans who attended a SUD residential treatment program at a VA facility found that 76% of veterans relapsed (Decker et al., 2017). Given the challenges faced by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and other healthcare settings to address the needs of veterans, substance abuse recovery homes, like Oxford House, are viable options for helping veterans recover from SUDs.

A socially supportive abstinent environment like the ones found in OHs may be especially beneficial to veterans with SUDs, as these settings provide general and recovery-specific social support thought to be the primary mechanism by which OH residences facilitate recovery, personal transformation, and reintegration into society. In general, a supportive social network of abstinent individuals is known to function as a protective factor for those in recovery (Moos, 2007; Vaillant, 1983). The social benefits that veterans can obtain from other OH residents are contingent on them forming strong, cohesive social connections within these homes. However, their capacity to form these connections with other OH residents may depend on the extent that they identify with other residents. Research on veterans shows that they have a preference for engaging socially with other veterans (Laffeye, Cavella, Drescher, & Rosen, 2008), suggesting that they may be more likely to develop stronger relationships with similar others in OHs who share their veteran status. It is possible that the social networks of veterans residing with other veterans in OHs will be more cohesive and have more ties compared to veterans living with only non-veterans. The literature on homophily (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001) and social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) would support such propositions. Below, we provide a review on social networks and recovery to establish why social network cohesion is important for veterans in recovery.

Social Networks and Recovery

Social networks have important implications for recovery from SUDs. Social networks and their associated norms influence the initiation and maintenance of substance use (Hawkins, Catalona, & Miller, 1992), and attrition from substance use treatment (Dobkin, Civita, Paraherakis, & Gill, 2002). Additionally, social support and support for abstinence predict a lower risk of relapse (Ellis, Bernichon, Yu, Roberts, & Herrell, 2004; Havassy, Hall, & Wasserman, 1991; Zywiak et al. (2009) and higher quality of life (Best et al., 2016).. In a study in which people who completed a detoxification treatment from alcohol were randomly assigned to either usual after-care or to a “network support” intervention which involved adding at least one non-drinking peer to their network (Litt, Kadden, Kabel-Cormier, & Perry, 2007; 2009). Those in the network support intervention had a 27% increased likelihood of treatment success at their one-year follow-up (Litt, Kadden, Kabel-Cormier, & Perry, 2007; 2009). Findings from a study that examined 1,726 adults who participated in Alcoholics Anonymous revealed that adaptive social network changes and increases in abstinence self-efficacy were the mechanisms that had the most significant influence on recovery (Kelly, Hoeppner, Stout, & Pagano, 2012).

Although social network studies of military samples are limited, a few studies indicate that social network characteristics may influence substance use and the recovery of this population. Among veterans in recovery from SUDs, higher-quality social networks mediated the relationship between involvement in self-help groups and reduced substance use at a one-year follow-up (Humphreys, Mankowski, Moos, & Finney, 1999). Among Army Reserve and National Guard service members, a greater number of connections with individuals that engage in alcohol or drug use, and higher average drinking days between service members and their social ties were associated with a higher risk for alcohol use problems (Goodell, Johnson, Latkin, Homish. & Homish, 2020). On the other hand, having a greater number of military-affiliated social ties reduced the risk of alcohol use problems, particularly among service members that had deployed. Harrison, Timko, and Blonigen (2013) examined substance abuse outcomes among veterans in a residential SUD treatment and found that having poorer relationships with peers in the treatment program predicted more SUD symptoms one-year after discharge.

Social Network Cohesion

Cohesion is an important social network characteristic that provides insights into how individuals of a network are socially embedded. A social network is considered cohesive to the extent that its members are connected to others in the network, and the extent that pairs of its members have multiple social connections within the group that pull the network together (White & Harary, 2001). Network cohesion is associated with positive outcomes, such as work-group performance and psychological well-being (Beal, Cohen, Burke, & McLendon, 2003; Mullen & Cooper, 1994). Members of a cohesive group demonstrate a high preference to interact with one another, more than with others outside of the group, and demonstrate highly self-preference segregative attitudes or behaviors (Fershtman, 1997). Cohesive social networks also demonstrate high morale, trust, friendship, cooperation, communication, commitment, and high identification with the group (Andrews, Kacmar, Blakely, & Bucklew, 2008; Carless & DePaola, 2000, Chen, Tang & Wang, 2009; Friedkin, 2004; Kidwell, Mossholder, & Benett, 1997; McLeod & Treuer, 2013).

Moreover, cohesive networks facilitate recovery social capital and social control - processes that are among the hypothesized crucial ingredients in the effective treatment of SUDs (Best, & Laudet, 2010; Cloud and Granfield 2008; Moos, 2007; 2008). Recovery social capital, which draws on the social capital literature (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988), is a set of resources that are obtained through one’s relationships that help facilitate recovery from SUDs (Best, & Laudet, 2010; Hennessy, 2017; Vilsaint et al., 2017). Recovery social capital can be obtained from various recovery supportive social relationships, including from family and friends. Further, according to social control theory, cohesive ties with others that are abstinent promotes social norms and sanctions that motivates individuals to refrain from substance use and helps them maintain their recovery (Moos, 2007; 2008). If these social ties are weak or absent, the individual is more likely to engage in problematic behaviors such as substance use. Due to the importance of cohesive social networks on recovery, further understanding of how these connections among veterans in OHs can be facilitated is needed. The current study defined recovery social capital as having cohesive social networks within OHs.

Homophily and Social Identity Theory

Military veterans have been studied as a community with a distinct culture and social identity (Hall, 2011; Koenig, Maguen, Monroy, Mayott, & Seal, 2014). The veteran identity is defined as veterans’ self-concept that derives from their previous military experience within a post-military service context (Harada et al., 2002). Service members are acculturated into military culture during basic training, which transforms their civilian identity into a military identity (Demers, 2011; Smith & True, 2014). Veterans constitute a distinct subculture because they have their own shared language, norms, and beliefs that distinguish veterans from civilians (Reger, Etherage, Reger, & Gahm, 2008). Although each branch of the military has cultural components unique to that service, there are vast cultural components shared across branches.,

The construct homophily provides some insights on the formation of interpersonal bonds, and research in this area suggests that veterans may be more likely to form connections in OHs where they have others that share their veteran status (Brissette, Cohen, & Seeman, 2000; McPherson et al., 2001; Smith, McPherson, & Smith-Lovin, 2014). Homophily refers to the social phenomenon in which people tend to develop relationships or have more frequent contact with others who share surface-level attributes (e.g. age, gender, race, ethnicity, occupation) or deep-level attributes (e.g. personality, cognitive ability, beliefs) (Flatt, Agini, & Albert, 2012; McPherson et al., 2001). Patterns of homophily have been found across different relationship types, and have been found to be critical to the formation of social connections (Fu, Nowak, Christakis, & Fowler, 2012; Lewis, Gonzales, & Kaufman, 2012; Smith et al., 2008). ).

The social identity theory (SIT; Tajfel & Turner, 1979; 1986) can also be used to understand why veterans may more easily form cohesive ties with each other. SIT is a social psychological theory of intergroup relations and the social self. The theory emphasizes the importance of group memberships and their significant effects on behavior. SIT postulates that people define their sense of self in terms of group memberships. People have a repertoire of discrete group memberships that differ in the extent to which they are perceived to be psychologically meaningful descriptors of the self (Haslem, Jetten, Postmes, & Haslam, 2009; Hogg, Terry & White, 1995; Jetten & Pachana, 2012; Roccas & Brewers, 2002; Oakes, 1987; Sani & Bennett, 2009; Stryker, 1980). Self-categorization and social comparison are two critical socio-cognitive processes involved in social identity formation and intergroup relations that result in the accentuation of the perceived similarities between the self and the in-group, and the accentuation of the differences between the out-group and the self (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Stets et al., 2000; Stets & Burke, 2000).

Although veterans belong to multiple social groups and to groups of different types, the veteran identity is considered to be particularly salient and central to veterans’ concept of the self (Adams et al., 2019; Atuel & Castro, 2018; Harada, Villa, Reifel, & Bayhylle, 2005). The prominence of this identity has influence over veterans’ well-being and behavior (Di Leone, Wang, Kressin, & Vogt, 2016; Firmin, Luther, Lysaker, & Salyers, 2016; Harada et al., 2002), including how they socialize with others and how they utilize support (Gorman, Scoglio, Smolinsky, Russo, & Drebing, 2018; Gade & Wilkins, 2012). Research on veterans shows that they are more likely to engage socially with other veterans, suggesting that they have stronger relationships with similar others (Ahern et al., 2015; Gorman, Scoglio, Smolinsky, Russo, & Drebing, 2018; Jain et al., 2016; Laffeye, Cavella, Drescher, & Rosen, 2008). Veteran status is a significant point of connection and for homophilic friendship formation. However, the tendency for veterans to form bonds with those that share their veteran identity can hinder the formation of cohesive ties with non-veterans in OHs.

Although veterans in OHs share an identity associated with recovery with other OH residents, they may still experience difficulties connecting with other residents. In a study examining identification issues among OH residents, veterans reported that their veteran status made it difficult to identify with other residents. The study also found that veterans’ difficulties with relating to other residents were associated to lower levels of abstinence social support and abstinence self-efficacy. These results suggests that identifying as a veteran may be more salient than identifying as an individual in recovery for veterans living in OHs, and thus it may be easier for them to develop connections with other veterans in OH. This finding is consistent with the body of literature that indicates that social support is more likely to be given, received, and interpreted positively to the extent that the individual on the receiving end of the support perceives themselves to share a social identity (Haslam et al., 2009). This is also true for individuals in recovery, with research suggesting that identity similarities moderates the impact of social network support on recovery (Beckwith, Best, Dingle, Perryman, and Lubman 2015; Best et al., 2016; Haslam, O’Brien, Jetten, Vormedal, & Penna, 2005; Jettern, Haslam, Haslam, Dingle, & Jones, 2014; Vik, Grizzle, & Brown, 1992). For instance, a study on OH residents found that similarities between residents and their housemates predicted greater satisfaction with the recovery home and longer length of stays (Beasley, Jason, & Miller, 2012).

Current Study

Given that veterans tend to identify more with other veterans, they may build stronger bonds with other veterans living in OHs than with non-veteran residents. Thus, veterans that reside with other veterans may have more cohesive social networks, and in turn, may benefit more from social processes i.e. social control and recovery social capital. Social network analysis and multi-level modeling were used to investigate whether veterans that live with other veterans have more cohesive social networks. Social network cohesion was operationalized as having greater close friendship network density. Density is a measure of interconnectedness in a social network and is quantified as the proportion of all close friendship relationships out of all possible close friendships for each OH resident. We hypothesized that networks with multiple veterans would have higher close friendship network density compared to networks with just one veteran.

Method

Participants

This study included 85 participants from 13 all male OHs. Each house had an average of 6.54 residents. Their mean age of 37.37 years (SD = 10.57). Participants identified as White (81.2%), African American/Black (7%), American Indian (7%), and Latinx (6%). The average length of stay in an OH was 8.9 months (SD = 9.44, range from 2 days to 4 years). Seventy-six percent of participants were non-veterans and 24% were veterans. Table 1 presents participant demographics across house compositions.

Table 1.

Demographics of participants in houses with one veteran and houses with two or more veterans

| Houses with one veteran (N = 40) | Houses with two or more veterans (N = 45) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Age | 37.76 (11.68) | 36.97 (9.74) |

| Length of Staya | 9.35 (11.20) | 8.70 (7.56) |

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Veteran Status | ||

| No | 33 (47.6) | 32 (55.6) |

| Yes | 7 (35) | 13 (65) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 33 (82.5) | 35 (79.5) |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 5 (12.5) | 1 (2.3) |

| Hispanic | 2 (0.05) | 2 (0.05) |

| American Indian | ----- | 6 (13.6) |

| Educational achievement | ||

| High school diploma or GED | 19 (50) | 20 (45.5) |

| Some college or training/technical degree | 18 (47.4) | 19 (43.2) |

| College degree or above | 1 (2.6) | 5 (11.4) |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time | 29 (72.5) | 32 (71.1) |

| Part-time | 3 (7.5) | 6 (13.3) |

| Unemployed | 6 (15) | 4 (8.9) |

| Other (student, service, retired/disabled) | 2 (5) | 3 (6.7) |

| Drug of First Choice | ||

| Alcohol | 11 (28.9) | 15 (34.9) |

| Marijuana | ---- | 3 (7) |

| Cocaine | 10 (26.3) | 4 (9.3) |

| Methamphetamine | 7 (18.4) | 14 (32.6) |

| Opiates and Sedatives | 10 (26.3) | 7 (16.3) |

| Region | ||

| North Carolina | 9 (22.5) | ----- |

| Texas | 25 (62.5) | 6 (13.3) |

| Oregon | 6 (15) | ----- |

| Oklahoma | ----- | 39 (86.7) |

Note: Length of stay is measured in months.

p < 0.05

p<0.005.

Procedures

The current study included 7 OHs with only one veteran in the residence and 6 OHs with two or more veterans. Data were collected from OHs located in Oklahoma, North Carolina, Texas, and Oregon. The participating houses from North Carolina, Texas, and Oregon were part of a longitudinal study which collected information every four months over a 2-year period (the current study involves baseline data). The longitudinal study aimed to examine the social networks and substance use recovery trajectories of OH residents. Participants completed measures of their demographics, stress, self-esteem, support, abstinence self-efficacy, hope, and social networks. Houses from these three different geographical regions were included to increase the generalizability of findings. State organizations helped the field staff assemble lists of residences to approach, and recruitment attempts were made in approximately in the order that resident contact information became available. Member-elected house presidents were asked to introduce the study to residents by reading a description of it from a project-provided script during a house meeting. Five additional OHs were recruited from Oklahoma to include houses with two or more veterans. Workers from the Oklahoma OH state organization identified the houses with two or more veterans. The OHs from Oklahoma were recruited exclusively for the current study and were not a part of the longitudinal study. Therefore, participants from the Oklahoma houses only provided baseline data. Houses were accepted into the study if the house president and all other members (or all but, at most, one member) agreed to participate. Houses were further excluded from the current study if they had no veteran residents.

All participants were interviewed by field research staff during individual face-to-face meetings. The interview began with an overview of the study in which participants were told of the voluntary nature of the study and were assured of confidentiality. All participants signed written consent forms. The consent forms for participants residing in OHs located in North Carolina, Oregon, and Texas granted permission for reassessment every four months over two years. Interviews consisted of only quantitative measures and lasted between 45 to 60 minutes for completion. Each questionnaire was assigned a random identification number to ensure participant confidentiality. Participants were compensated $20 for completing their interviews. Permission to do this study was obtained by the DePaul University Institutional Review Board (IRB Protocol#LJ072314PSY-R9). All participants were provided with the Principle Investigator and the IRB’s contact information.

Measures

Demographics.

Participant demographics were collected including veteran status, age, race/ethnicity. Participants’ log of the length of stay in months were computed and used as a continuous variable. The battery of measures also included questions regarding length of substance use, comorbidity, length of sobriety, and drug of choice.

House Composition.

OHs were dichotomized into houses with only one veteran and houses with two or more veterans, and were coded as 0 and 1, respectively.

Length of Stay.

Length of stay in Oxford House (LOS) is a continuous variable that details the amount of time residents have been living in an OH. Participants’ log of the length of stay in months were computed and was used a covariate.

Social Network Cohesion.

The Social Network Instrument (SNI; Jason & Stevens, 2017) was utilized to capture individual-level social network cohesion. This instrument has been used in several investigations on the social networks of recovery home residents (Jason et al., 2014; Jason & Stevens, 2017; Jason et al., 2018; Light et al., 2016). The SNI measures six relationship characteristics, including friendship, willingness to lend resources, advice-seeking, help, strength, and frequency. Each participant were asked to rate all other residents in their OH on each of these six items. The current study only looked at friendship. Friendship, which taps into non-judgmental social support, was determined by asking “How friendly are you with this person?” This item was rated on a 5-point likert scale (0 =“close friend;” 1 = “friend;” 2 = “acquaintance;” 3 = “stranger;” 4 = “adversary”).

The current study examined social network cohesion using close friendship density as a proxy. A close friendship tie or relationship was considered present if a participant nominated another resident as a ‘close friend.’ Close friendship was selected as our threshold given our study’s aim to examine cohesive networks which are a result of close relationships between network members. Density is the proportion of all close friendship relationships out of all possible close friendships for each OH resident. The values for density range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more connections and lower values indicating fewer connections with others in the network. The first step in calculating density is to create adjacent matrices of participant’s friendship ratings, which are measured on a scale of 0 to 4. The rows of the matrices signify an ego (senders of friendship nominations) and columns signify alters (receivers of friendship nominations). The second step is to transform the friendship ratings into binary nominations. If a close friendship nomination was present between an ego and an alter this would represent a degree. All values were dichotomized (0 = no degree; 1 = degree) and entered into the corresponding element of the matrix. Lastly, the density for each participant were then calculated by averaging the sum of close friendship out-degree by the number of possible close friendship out-degrees. An out-degree is a rating that the ego makes about an alter. An in-degree, which are a rating that an alter makes about an ego were not used to calculate density scores given our focus on how individuals perceive others in their networks, and not on how others in their networks perceive them. The steps involved in calculating density are represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The steps to calculating density scores for each participant. The sociogram on the left presents an example of a network with three members (A, B, C). In Step 1, participant’s friendship ratings measured on a 5-point likert scale that ranged from ‘close friend’ (0) to “adversary” (4) are put into adjacent matrices with ratings for each possible combination of ego and alters. In step 2, friendship nominations are transformed into binary nominations, with close friendships entered as “1” and non-close friendship nominations entered as “0.” In step 3, the proportion of close friendship nominations over all possible close friendships are averaged to calculate density scores for each ego in the network.

Analytic Approach

Given the nested design of the data (i.e. residents nested into houses), the intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC1) were generated for friendship density, to determine the amount of variance that could be explained at the house level. The ICC1 for friendship density was .15, indicating that 15% of the variation in friendship density could be explained at the house level. Thus, analysis proceeded utilizing random effects multi-level models. Multi-level modeling is appropriate for analyzing non-independent nested data, given that responses from individuals nested in the same groups are more similar than what we would expect them to be by mere chance (Bliese, Maltarich, & Hendricks, 2018). To test our hypothesis, a multilevel model was run using the lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) statistical package in R to determine whether there was a cross-level interaction between house composition and veteran status on friendship density. Houses were used as a random intercept. Veteran status, house composition, and the interaction between these two variables were entered into the models as a fixed effect. Length of stay and network size were used as a covariate and these were also entered into the models as fixed effects. House composition was measured at the macro-level and all other variables were measured at the micro-level. A plot of estimated marginal means was generated to display differences in friendship density across veteran status and house composition (Figure 2). Lastly, visual representations (i.e. sociograms) of friendship networks for each house composition were generated using the igraph package (Csardi & Nepusz, 2006) (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Plot of estimated marginal means of friendship density with house composition by veteran status after controlling for length of stay and network size

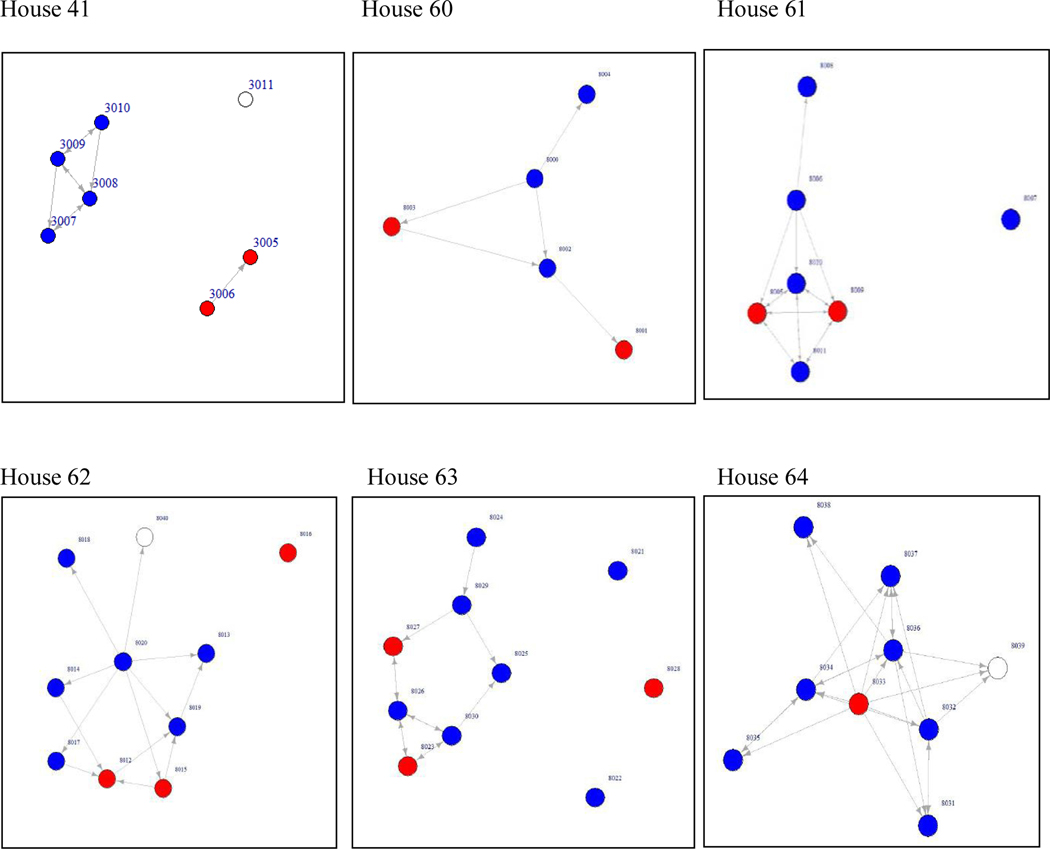

Figure 3.

Sociograms of friendship networks for houses with one veteran. Red nodes are veterans, blue nodes are non-veterans, and white nodes are non-participants

Figure 4.

Sociograms of friendship networks for houses with more than one veteran. Red nodes are veterans, blue nodes are non-veterans, and white nodes non-participants. Participant 8039 in House 64 did not participate in the study but self-identified as a veteran.

Results

The variance components of the null model for Level 1 were σ2 = 0.06 and Level 2 were τ = 0.01 for an ICC of .15, χ2 (12) = 0.20, p < .001 (Table 2). A multilevel model with the parameters of the fixed effects for the individual level predictor, house level predictor, and the cross-level interactions are displayed in Table 3. Overall, a significant relationship was found between friendship density and the house in which participants reside in. Thus, analysis proceeded utilizing a random effects model and individual level predictors were added to investigate the possible relation between veteran status and house composition to friendship density, while controlling for length of stay and network size. Results revealed that house composition was significantly related to friendship density (β = .16, SE = 0.08, p < .0.05), indicating both veterans and non-veterans in houses with multiple veterans tended to have greater close friendships, and thus more cohesive networks. A plot of the estimated marginal means for friendship density by house composition and veteran status, while accounting for length of stay and network size are displayed in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Null model of friendship density at the house level

| Estimates | CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.20 | 0.12–0.27 | 0.001** |

| Random Effects | |||

| σ2 | 0.06 | ||

| τ00 | 0.01 | ||

| ICC | 0.15 | ||

| N | 13 | ||

| Observations | 84 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.000/0.151 |

Note. p<0.005

Table 3.

Final estimation of fixed effects for multilevel model predicting friendship density

| Estimates | CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.17 | −0.10–0.43 | 0.23 |

| Veteran status | −0.05 | −0.24–0.14 | 0.63 |

| House composition | 0.16 | 0.01–0.31 | 0.04* |

| Log of length of stay | 0.04 | −0.00–0.08 | 0.05 |

| Network size | −0.01 | −0.05–0.02 | 0.42 |

| Veteran status*house composition | 0.06 | −0.18–0.30 | 0.64 |

| Random Effects | |||

| σ2 | 0.05 | ||

| τ00 | 0.00 | ||

| ICC | 0.06 | ||

| N | 13 | ||

| Observations | 83 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.147/0.200 |

Note. p<0.05.

Discussion

The current study provides the first examination of social networks of veterans with substance use disorders living in recovery homes. Based on the literature on social identity theory (Turner & Tajfel, 1986), homophily (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001), and studies that suggest that veterans are more willing to socially engage with other veterans (Laffeye, Cavella, Drescher & Rosen, 2008), the present study investigated whether the social networks of veterans residing with other veterans were more cohesive compared to veterans living with only non-veterans. Overall, results showed residents in houses with more than one veteran had greater close friendship ties compared to houses with just one veteran. In particular, veterans residing with other veterans had more close friendships compared to veterans that live with only non-veterans. This pattern can be visually observed in the sociograms presented in Figures 3 and 4 and the plots of the estimated marginal means provided in Figure 2. The sociograms demonstrate that veterans that lived with only non-veterans tended to be the sole isolates in houses where other residents were connected with each other, compared to veterans living in houses with multiple veterans. Non-veterans also had greater network density in the houses with multiple veterans as shown by the plot of marginal means. This finding warrants further investigation to determine why houses with more veterans have greater network cohesion overall for both veterans and non-veterans.

Findings have several implications for theory and practice. Results suggest that veterans may benefit from living with other veterans when considering friendship density as a measure of network cohesion. While further research is needed before recommendations are made on how the OH model should be modified to best meet the needs of military veterans, results highlight the need to consider housing veterans with similar peers as a way to facilitate their development of connections within the homes. Peer support is recognized to improve the psychological well-being of veterans (MacEachron & Gustavsson, 2012). Peer support is also viewed to be congruent with veterans’ shared experience of military culture, which values comradery and unit cohesion (Barber, Rosenhack, Armstrong, & Resnick, 2008). However, personal networks represent chosen social affiliations, whereas OHs typically do not. For this reason, it may be that veterans feel particularly understood and supported in a house with other veterans, and therefore more likely to form connections when living with peers that share their veteran identity.

Previous research has shown that being connected to other OH residents is predictive of positive outcomes such as longer length of stay and lower relapse rates. For instance, Jason et al. (2012) found that social network size and the presence of positive relationships with other residents predicted future abstinence in an OH. In addition, individuals with other OH residents as part of their social networks were more likely to remain in an OH six months and were less likely to relapse. Furthermore, a cohesive house social ecology was found to mediate the rates of relapse (Jason, Davis, Ferrari, & Anderson, 2007; Jason, Olson et al., 2006; Jason et al., 2012). These studies demonstrate that having other OH residents in one’s social network is one of the most predictive factors of successful recovery; therefore, our finding that veterans living with other veterans have greater friendship density is important.

We found no interaction between veteran status and house composition. However, the interaction of veteran status and house composition did not differentiate between veterans living in either type of house composition. Rather, it compared veterans to non-veterans in both types of homes. This finding reveals that there are no differences in social network cohesion among veterans compared to non-veterans living in either type of house composition, with both veterans and non-veterans having higher social network cohesion compared those who live in houses with a single veteran. This finding suggests that houses with multiple veterans are as beneficial to veterans and non-veterans alike. However, consistent with our hypothesis, an examination of the plot of estimated marginal means (Figure 2) revealed that veterans living with multiple veterans do have greater friendship density compared to veterans living with all non-veterans, after controlling for both network size and length of stay.

Further, although based on the literature on homophily and social identity theory one could have expected to see veterans clustering in the houses with multiple veterans, this was not the case. Veterans in houses with multiple veterans tended to be connected to both veterans and non-veterans (see Figure 4). It may be the case that having the presence of a similar other in the house can help facilitate connections with other less similar residents.

There are several limitations in the current study that should be taken into consideration when interpreting our findings. The overall sample is homogenous in regards to demographic characteristics such as race/ethnicity and sex. Although houses with only one veteran were recruited from three different regions in the US, five out of the six houses with two or more veterans were recruited from Oklahoma. Thus, findings may reflect a region effect. Furthermore, data from these houses do not represent a random sample. Future studies should collect data from a national sample to increase the generalizability of the findings. other unexplored identities may play a role in the differences found between the two types of houses. The only demographic differences between residents in the two types of houses was ethnicity when examining the proportion of American Indians. For instance, 13.6% of the residents in houses with multiple veterans were American Indian compared to no American Indians in the houses with a single veteran. However, only two of these individuals resided in the same house, suggesting that it is unlikely that this demographic difference had an effect on social network cohesion. No other differences were found in terms of length of stay,, age, and drug of first choice across house composition. Lastly, the study’s cross-sectional design does not allow for causal inferences to be made and limits interpretations on the temporal sequence of the relationships between our variables.

Despite these limitations, our findings highlight the need for additional research to understand further the social networks of veterans in recovery and the dynamics of having multiple veterans in recovery homes. A potential future direction would be to explore different thresholds or proportion of veterans per house that would be most beneficial for veterans. It is possible that houses with a mix of veterans and non-veterans would be the most beneficial for veterans, rather than living veterans living exclusively with other veterans. Mixed homes would allow veterans to form connections with those that share their military culture and veteran identity, and it would also allow veterans to derive benefits from non-veterans including learning how to reintegrate with civilians and how to connect with others that do not share their military identity, which are difficulties many veterans face after leaving the military (Demers, 2011; Orazem et al., 2017; Smith & True, 2014). In addition, longitudinal research should be conducted to examine the evolution of the connections veterans form in homes with different house composition and how these tie formations predict long-term recovery outcomes such as relapse, abstinence self-efficacy, and longer length of stays in recovery homes. Our study also only examined the in-house social networks of veterans. Therefore future research should explore how these in-house networks affect veterans’ out-of-the-house networks (e.g., social media, family), and their combined influence on a veterans’ recovery.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the financial support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant number AA022763). The authors appreciate the help of John Light and Nate Doogan. We also acknowledge the members of the Oxford House organization, and in particular Paul Molloy, Alex Snowden, Casey Longan, and Howard Wilkins.

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article. The study described was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant number AA022763). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams RE, Urosevich TG, Hoffman SN, Kirchner HL, Hyacinthe JC, Figley CR, Withey CA, Boscarino JJ, & Boscarino JA (2017). Social support, help-seeking, and mental health outcomes among veterans in non-VA facilities: results from the veterans’ health study. Military Behavioral Health, 5(4), 393–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Crawford EF, & Kudler H. (2016). Nature and treatment of comorbid alcohol problems and post-traumatic stress disorder among American military personnel and veterans. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38(1), 133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aase DM, Jason LA, Olson BD, Majer JM, Ferrari JR, Davis MI, & Virtue SM (2009). A longitudinal analysis of criminal and aggressive behaviors among a national sample of adults in mutual-help recovery homes. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 4(1–2), 82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern J, Worthen M, Masters J, Lippman SA, Ozer EJ, & Moos R. (2015). The challenges of Afghanistan and Iraq veterans’ transition from military to civilian life and approaches to reconnection. PlOS ONE, 10(7), e0128599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TL (1998). A cultural-identity theory of drug abuse. Sociology of Crime, Law, and Deviance, 1, 233–262. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews MC, Kacmar KM, Blakely GL, & Bucklew NS (2008). Group cohesion as an enhancement to the justice—affective commitment relationship. Group and Organization Management, 33(6), 736–755. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth BE, & Mael F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Atuel HR, & Castro CA (2018). Military cultural competence. Clinical Social Work Journal, 46(2), 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Barber JA, Rosenheck RA, Armstrong M, & Resnick SG (2008). Monitoring the dissemination of peer support in the VA Healthcare System. Community Mental Health Journal, 44(6), 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, & Walker S. (2014). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Beal DJ, Cohen RR, Burke MJ, & McLendon CL (2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: a meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley CR, Jason LA, & Miller SA (2012). The general environment fit scale: A factor analysis and test of convergent construct validity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith M, Best D, Dingle G, Perryman C, & Lubman D. (2015). Predictors of flexibility in social identity among people entering a therapeutic community for substance abuse. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 33(1), 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E. (1985). Interpersonal attraction. Handbook of Social Psychology, 2, 413–484. [Google Scholar]

- Best D, Beckwith M, Haslam C, Alexander Haslam S, Jetten J, Mawson E, & Lubman DI (2016). Overcoming alcohol and other drug addiction as a process of social identity transition: The Social Identity Model of Recovery (SIMOR). Addiction Research & Theory, 24(2), 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Best D, & Laudet A. (2010). The potential of recovery capital. London: RSA. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki P. (1986). Pathways from heroin addiction: Recovery without treatment. Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bliese PD, Maltarich MA, & Hendricks JL (2018). Back to basics with mixed-effects models: Nine take-away points. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Timko C, Finney JW, Moos BS, & Moos RH (2011). Alcoholics Anonymous attendance, decreases in impulsivity and drinking and psychosocial outcomes over 16 years: Moderated‐mediation from a developmental perspective. Addiction, 106(12), 2167–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. (1986). The forms of capital. In Granovetter M, Swedberg R. (3rd), The sociology of economic life. [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Brown JM, & Williams J. (2013). Trends in binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and combat exposure in the US military. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(10), 799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette I, Cohen S, & Seeman TE (2000). Measuring social integration and social networks. In Cohen S, Underwood L, & Gotlieb B. (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 53–85). New York, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham SA, Frings D, & Albery IP (2013). Group membership and social identity in addiction recovery. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(4), 1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carless SA, & De Paola C. (2000). The measurement of cohesion in work teams. Small Group Research, 31(1), 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CHV, Tang YY, & Wang SJ (2009). Interdependence and organizational citizenship behavior: Exploring the mediating effect of group cohesion in multilevel analysis. The Journal of Psychology, 143(6), 625–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud W, & Granfield R. (2008). Conceptualizing recovery capital: Expansion of a theoretical construct. Substance Use & Misuse, 43(12–13), 1971–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59(8), 676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Janicki-Deverts D. (2009). Can we improve our physical health by altering our social networks? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(4), 375–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Csardi G, & Nepusz T (2006). “The igraph software package for complex network research.” InterJournal, Complex Systems, 1695. http://igraph.org. [Google Scholar]

- Decker KP, Peglow SL, Samples CR, & Cunningham TD (2017). Long-term outcomes after residential substance use treatment: Relapse, morbidity, and mortality. Military Medicine, 182(1–2), e1589–e1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers A. (2011). When veterans return: The role of community in reintegration. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 16(2), 160–179. [Google Scholar]

- Di Leone BA, Wang JM, Kressin N, & Vogt D. (2016). Women’s veteran identity and utilization of VA health services. Psychological Services, 13(1), 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingle GA, Stark C, Cruwys T, & Best D. (2015). Breaking good: Breaking ties with social groups may be good for recovery from substance misuse. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54(2), 236–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin PL, Civita MD, Paraherakis A, & Gill K. (2002). The role of functional social support in treatment retention and outcomes among outpatient adult substance abusers. Addiction, 97(3), 347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis B, Bernichon T, Yu P, Roberts T, & Herrell JM (2004). Effect of social support on substance abuse relapse in a residential treatment setting for women. Evaluation and Program Planning, 27(2), 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Erbes C, Westermeyer J, Engdahl B, & Johnsen E. (2007). Post-traumatic stress disorder and service utilization in a sample of service members from Iraq and Afghanistan. Military Medicine, 172(4), 359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargo J, Metraux S, Byrne T, Munley E, Montgomery AE, Jones H, Sheldon G, Kane V, & Culhane D. (2012). Prevalence and risk of homelessness among US veterans. Preventing Chronic Disease, 9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fershtman M. (1997). Cohesive group detection in a social network by the segregation matrix index. Social Networks, 19(3), 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Fink DS, Gallaway MS, Tamburrino MB, Liberzon I, Chan P, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Shirley E, Goto T, D’Arcangelo N, Fine T, Reed PL, Calabrese JR, & Galea S. (2016). Onset of Alcohol Use Disorders and Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in a Military Cohort: Are there Critical Periods for Prevention of Alcohol Use Disorders? Prevention Science, 17(3), 347–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firmin RL, Luther L, Lysaker PH, & Salyers MP (2016). Veteran identity as a protective factor: A grounded theory comparison of perceptions of self, illness, and treatment among veterans and non-veterans with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 19(4), 294–314. [Google Scholar]

- Flatt MJD, Agimi MY, & Albert SM (2012). Homophily and health behavior in social networks of older adults. Family & Community Health, 35(4), 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedkin NE (2004). Social cohesion. Annual Review of Sociology, 409–425. [Google Scholar]

- Fu F, Nowak MA, Christakis NA, & Fowler JH (2012). The evolution of homophily. Scientific Reports, 2, 845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gade DM, & Wilkins VM (2012). Where did you serve? Veteran identity, representative bureaucracy, and vocational rehabilitation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(2), 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Vazan P, Bennett AS, & Liberty HJ (2013). Unmet need for treatment of substance use disorders and serious psychological distress among veterans: a nationwide analysis using the NSDUH. Military Medicine, 178(1), 107–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell EMA, Johnson RM, Latkin CA, Homish DL, & Homish GG (2020). Risk and protective effects of social networks on alcohol use problems among Army Reserve and National Guard soldiers. Addictive Behaviors, 103, 106244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman JA, Scoglio AA, Smolinsky J, Russo A, & Drebing CE (2018). Veteran coffee socials: a community-building strategy for enhancing community reintegration of veterans. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(8), 1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LK (2011). The importance of understanding military culture. Social Work in Health Care, 50(1), 4–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada ND, Damron-Rodriguez J, Villa VM, Washington DL, Dhanani S, Shon H, Chattopadhya M, Fishbein H, Lee M, Makinodan T, & Andersen R. (2002). Veteran identity and race/ethnicity: influences on VA outpatient care utilization. Medical Care, 40(1), I–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada ND, Villa VM, Reifel N, & Bayhylle R. (2005). Exploring veteran identity and health services use among Native American veterans. Military Medicine, 170(9), 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DA, Price KH, & Bell MP (1998). Beyond relational demography: Time and the effects of surface-and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison AJ, Timko C, & Blonigen DM (2017). Interpersonal styles, peer relationships, and outcomes in residential substance use treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 81, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam SA, Jetten J, Postmes T, & Haslam C. (2009). Social identity, health and well‐being: an emerging agenda for applied psychology. Applied Psychology, 58(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam SA, O’Brien A, Jetten J, Vormedal K, & Penna S. (2005). Taking the strain: Social identity, social support, and the experience of stress. British Journal of Social Psychology, 44(3), 355–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havassy BE, Hall SM, & Wasserman DA (1991). Social support and relapse: Commonalities among alcoholics, opiate users, and cigarette smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 16(5), 235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, & Miller JY (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy EA (2017). Recovery capital: A systematic review of the literature. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(5), 349–360. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, Terry DJ, & White KM (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hoggatt KJ, Lehavot K, Krenek M, Schweizer CA, & Simpson T. (2017). Prevalence of substance misuse among US veterans in the general population. American Journal on Addictions, 26, 357–365. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, & Umberson D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865), 540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Mankowski ES, Moos RH, & Finney JW (1999). Do enhanced friendship networks and active coping mediate the effect of self-help groups on substance abuse? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 21(1), 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, McLean C, Adler EP, & Rosen CS (2016). Peer support and outcome for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a residential rehabilitation program. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(8), 1089–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Davis MI, Ferrari JR, & Bishop PD (2001). Oxford House: A review of research and implications for substance abuse recovery and community research. Journal of Drug Education, 31(1), 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Davis MI, & Ferrari JR (2007). The need for substance abuse after-care: Longitudinal analysis of Oxford House. Addictive Behaviors, 32(4), 803–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, Ferrari JR, & Lo Sasso AT (2006). Communal housing settings enhance substance abuse recovery. American Journal of Public Health, 96(10), 1727–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, & Harvey R. (2015). Evaluating alternative aftercare models for ex-offenders. Journal of Drug Issues, 45(1) 53–68. PMCID: PMC4307799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason L, Stevens JRF, Thompson E, & Legler R. (2012). Social networks among residents in recovery homes. Advances in Psychology Study, 1(3), 4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J, Haslam C, Haslam SA, Dingle G, & Jones JM (2014). How groups affect our health and well‐being: the path from theory to policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 8(1), 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J, Haslam C, Haslam SA, Dingle G, & Jones JM (2014). How groups affect our health and well‐being: the path from theory to policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 8(1), 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Hoeppner B, Stout RL, & Pagano M. (2012). Determining the relative importance of the mechanisms of behavior change within Alcoholics Anonymous: A multiple mediator analysis. Addiction, 107(2), 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsall HL, Wijesinghe MSD, Creamer MC, McKenzie DP, Forbes AB, Page MJ, & Sim MR (2015). Alcohol use and substance use disorders in Gulf War, Afghanistan, and Iraq War veterans compared with non-deployed military personnel. Epidemiologic Reviews, 37(1), 38–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell RE, Mossholder KW, & Bennett N. (1997). Cohesiveness and organizational citizenship behavior: A multilevel analysis using work groups and individuals. Journal of Management, 23(6), 775–793. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig CJ, Maguen S, Monroy JD, Mayott L, & Seal KH (2014). Facilitating Culture-centered communication between health care providers and veterans transitioning from military deployment to civilian life. Patient, Education, and Participation, 95, 414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer KL, McGinnis KA, Fiellin DA, Skanderson M, Gordon AJ, Robbins J, Zickmund, Bryant K, & Korthuis PT (2019). Low levels of initiation, engagement, and retention in substance use disorder treatment including pharmacotherapy among HIV-infected and uninfected veterans. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 103, 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffaye C, Cavella S, Drescher K, & Rosen C. (2008). Relationships among PTSD symptoms, social support, and support source in veterans with chronic PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(4), 394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan CW, Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Bryant KJ, Gordon AJ, Edelman EJ, Gaither JR, Maisto SA, & Marshall BD (2016). The epidemiology of substance use disorders in US Veterans: A systematic review and analysis of assessment methods. The American Journal on Addictions, 25(1), 7–24. 10.1111/ajad.12319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson MJ, Wooten NR, Adams RS, & Merrick EL (2012). Military combat deployments and substance use: review and future directions. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 12(1), 6–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A, Timko C, & Hill T. (2014). Comparing life experiences in active addiction and recovery between veterans and non-veterans: A national study. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 33(2), 148–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K, Gonzalez M, & Kaufman J. (2012). Social selection and peer influence in an online social network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(1), 68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E, & Petry N. (2007). Changing network support for drinking: Initial findings from the Network Support Project. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E, & Petry NM (2009). Changing network support for drinking: network support project 2-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacEachron A, & Gustavsson N. (2012). Peer support, self-efficacy, and combat-related trauma symptoms among returning OIF/OEF veterans. Advances in Social Work, 13(3), 586–602. [Google Scholar]

- Majer JM, Jason LA, Ferrari JR, & North CS (2002). Comorbidity among Oxford House residents: A preliminary outcome study. Addictive Behaviors, 27(5), 837–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majer JM, Jason LA, North CS, Ferrari JR, Porter NS, Olson B, ... & Molloy JP (2008). A longitudinal analysis of psychiatric severity upon outcomes among substance abusers residing in self-help settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 42(1–2), 145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannix E, & Neale MA (2005). What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6(2), 31–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod J, & Von Treuer K. (2013). Towards a cohesive theory of cohesion. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 3(12), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, & Cook JM (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH (2007). Theory-based active ingredients of effective treatments for substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(2), 109–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH (2008). Active ingredients of substance use‐focused self‐help groups. Addiction, 103(3), 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen B, & Copper C. (1994). The relation between group cohesiveness and performance: An integration. Psychological Bulletin, 115: 210–227. [Google Scholar]

- Neve RJ, Lemmens PH, & Drop MJ (1997). Gender differences in alcohol use and alcohol problems: mediation by social roles and gender-role attitudes. Substance Use & Misuse, 32(11), 1439–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes PJ (1987). The salience of social categories. In Turner JC (Ed.), Re-discovering the social group: A self-categorization theory (pp. 117–141). Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Orford J. (2001). Addiction as excessive appetite. Addiction, 96(1), 15–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orazem RJ, Frazier PA, Schnurr PP, Oleson HE, Carlson KF, Litz BT, & Sayer NA (2017). Identity adjustment among Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans with reintegration difficulty. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(S1), 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford House. (2008). Oxford House manual: An idea based on a sound system for recovering alcoholics and addicts to help themselves. Silver Spring, MD: Oxford House, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford House. (2015). Oxford House Inc. Annual Report FY 2015: Celebrating 40 years. Silver Spring, MD: Oxford House, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Reger MA, Etherage JR, Reger GM, & Gahm GA (2008). Civilian psychologists in an Army culture: The ethical challenge of cultural competence. Military Psychology, 20(1), 21. [Google Scholar]

- Roccas S, & Brewer MB (2002). Social identity complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(2), 88–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez L, & Smith JA (2014). ‘Finding Your Own Place’: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of young men’s experience of early recovery from addiction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 12(4), 477–490. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, & Fontana A. (1994). A model of homelessness among male veterans of the Vietnam War generation. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(3), 421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CS, Kuhn E, Greenbaum MA, & Drescher KD (2008). Substance abuse–related mortality among middle-aged male VA psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services, 59(3), 290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sani F, & Bennett M. (2009). Children’s inclusion of the group in the self: Evidence from a self–ingroup confusion paradigm. Developmental Psychology, 45(2), 503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Ren L. (2011). Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001–2010: Implications for screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 116(1–3), 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KP, & Christakis NA (2008). Social networks and health. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 405–429. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, McPherson M, & Smith-Lovin L. (2014). Social distance in the United States: Sex, race, religion, age, and education homophily among confidants, 1985 to 2004. American Sociological Review, 79(3), 432–456. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RT, & True G. (2014). Warring Identities Identity Conflict and the Mental Distress of American Veterans of the Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Society and Mental Health, 2156869313512212. [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE, & Burke PJ (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 224–237. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker S. (1980). Symbolic interactionism: A social structural version. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2007). Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED498206.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (2018). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Veterans Report: Substance use, dependence and treatment among veterans. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt23251/6_Veteran_2020_01_14.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner JC (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. The social psychology of intergroup relations, 33(47), 74. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Link B, Rosenheck RA, & Pietrzak RH (2016). Homelessness among a nationally representative sample of US veterans: prevalence, service utilization, and correlates. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(6), 907–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, & Tajfel H. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE (1983). The natural history of alcoholism: Causes, patterns, and paths to recovery. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vilsaint CL, Kelly JF, Bergman BG, Groshkova T, Best D, & White W. (2017). Development and validation of a Brief Assessment of Recovery Capital (BARC-10) for alcohol and drug use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 177, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik PW, Grizzle KL, & Brown SA (1992). Social resource characteristics and adolescent substance abuse relapse. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 2(2), 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner TH, Harris KM, Federman B, Dai L, Luna Y, & Humphreys K. (2007). Prevalence of substance use disorders among veterans and comparable nonveterans from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Psychological Services, Vol 4(3), 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- White DR, & Harary F. (2001). The cohesiveness of blocks in social networks: Node connectivity and conditional density. Sociological Methodology, 31(1), 305–359. [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak WH, Neighbors CJ, Martin RA, Johnson JE, Eaton CA, & Rohsenow DJ (2009). The Important People Drug and Alcohol interview: Psychometric properties, predictive validity, and implications for treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36(3), 321–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]