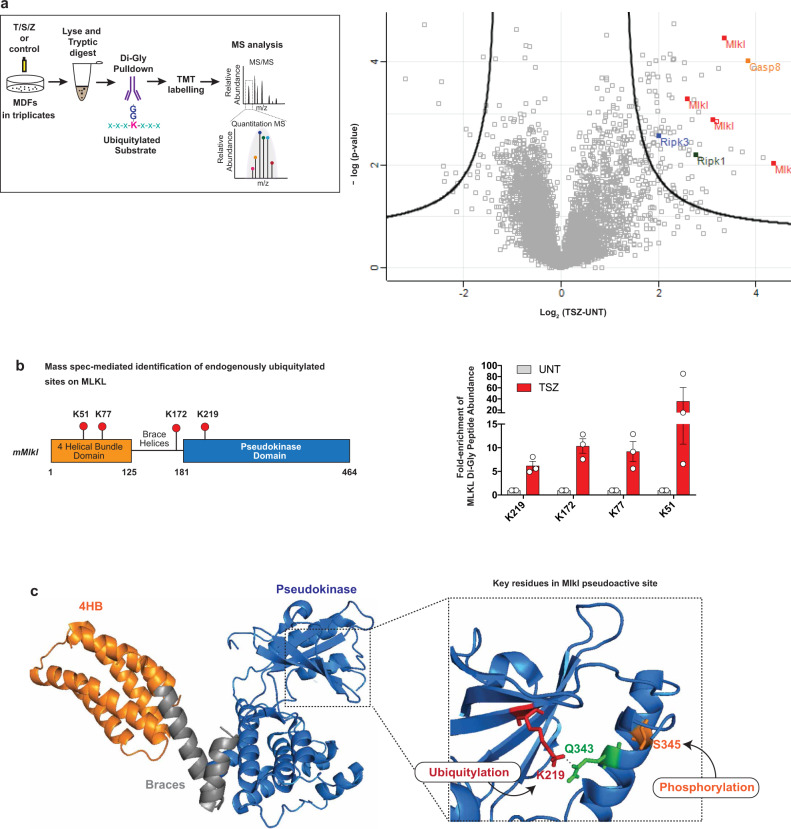

Fig. 4. Endogenous MLKL is ubiquitylated on K51, K77, K172 and K219.

a Mass spectrometry (MS)-based identification of ubiquitylated peptides. Left panel: schematic representation of the experimental design. Mouse dermal fibroblasts (MDF) were treated with TNF (10 ng/ml), SM-164 (100 nM) and z-VAD-FMK (20 μM; TSZ) for 2 h or left untreated. Extracted proteins were digested with trypsin and Ub remnants were enriched using an anti-K-ε-GG antibody. Six samples, corresponding to three biological replicates, were labelled with one of the tandem mass tags (TMT) 10-plex. Subsequently, samples were mixed, subjected to identification by LC–MS/MS and quantified using peak area under curve. Right panel: volcano plot of global peptide abundance showing −log p values versus log2 ratio changes between TSZ and untreated control. The three biological replicates were taken into consideration. Peptides corresponding to MLKL, RIPK1, RIPK3 and caspase-8 are indicated. b Schematic diagram depicting the domain architecture of murine MLKL and the identified Ub acceptor lysine (K), left panel. The graph depicts fold enrichment of the respective di-Gly peptide abundance. The result is representative of one independent experiment with three replicates for each treatment group. Data are presented as mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). c Crystal structure of murine MLKL (PBD:4BTF8) comprising the 4-helix bundle (4HB) domain (orange), the pseudokinase domain (blue) and the brace helices (grey). Magnification of the pseudoactive site of MLKL showing the hydrogen bond interaction between K219 and Q343. Residue S345 that is phosphorylated by RIPK3 is shown in orange.