Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study is to evaluate the effect of Vitamin D3 on symptoms, uterine and leiomyoma volume in women with symptomatic leiomyoma and hypovitaminosis D.

Materials and Methods:

In this pilot, interventional, prospective study, 30 premenopausal women with uterine leiomyoma and concomitant hypovitaminosis D (<30 ng/ml) received Vitamin D3 in doses of 60,000 IU weekly for 8 weeks followed by 60,000 IU every 2 weeks for another 8 weeks. Change in symptoms, uterine, and leiomyoma volume was evaluated at 8 weeks and 16 weeks. Serum Vitamin D3 levels were repeated at 16 weeks of therapy.

Results:

A significant negative correlation was observed between the baseline 25-hydroxy Vitamin D (25(OH) Vitamin D3) and leiomyoma volume (r = –0.434, P < 0.001). There was significant reduction of menstrual blood loss by 29.89% (P = 0.003) and severity of dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, and backache by 44.12%, 35%, and 50% (P < 0.001, 0.019, and 0.002), respectively, at 16 weeks. At end of therapy, there was 6% reduction in mean uterine volume and 11% in leiomyoma volume which was not significant. Serum 25(OH) Vitamin D3 was significantly higher than baseline level (17.44 ± 5.82 vs. 39.38 ± 8.22, P < 0.001) at end of therapy.

Conclusion:

Vitamin D3 supplementation is effective in reducing leiomyoma-related symptoms and stabilizing uterine and leiomyoma volume.

KEYWORDS: 25-hydroxy Vitamin D3, fibroid, hypovitaminosis D, leiomyoma, Vitamin D deficiency, Vitamin D insufficiency

INTRODUCTION

Uterine leiomyomas, the common benign tumors of the uterus are associated with significant symptoms which negatively impact women's health.[1] Treatment strategies, surgical or medical, are typically individualized based on severity of the symptoms, tumor characteristics, patient's age, wish to preserve the uterus, and patient's desire for future fertility. The main interest of today is on cost containment, use of conservative and nonsurgical techniques where-ever possible. Currently, there is no effective medical treatment for uterine leiomyoma, and it is only used for short-term therapy.[2,3]

The initiating factors that lead to the development of fibroids are not well understood. It has recently been suggested that Vitamin D deficiency may play an important role in the development of uterine leiomyoma. 1,25Di(OH) Vitamin D3 (1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3) is the biologically active form of Vitamin D3 which suppresses proliferation of both normal and malignant cells, and it induces differentiation and apoptosis.[4] Various studies have documented an association between low Vitamin D reserve with leiomyoma.[5,6,7,8] In vitro study by Halder et al. showed that both myometrial and leiomyoma cells are highly sensitive to regulatory effect of 1,25(OH) Vitamin D3.[9]

Halder et al. conducted a first preclinical trial in an in vivo model of leiomyoma in female Eker rats to determine the antitumor and therapeutic effects of 1,25Di(OH) Vitamin D3 on uterine leiomyoma. Vitamin D3 resulted in significant reduction (75% ± 3.85%) in leiomyoma size over a period of 4 weeks,[10] so a need was felt for the in vivo study on the human subjects, and the present study was initiated as a pilot project in 2015. However, recently, a similar study has been published showing that Vitamin D supplementation in uterine fibroids with concomitant hypovitaminosis Vitamin D reduces the progression to extensive disease.[11]

On the basis of above-mentioned evidences, it is proposed that there exists a possible mechanism of benefit rendered by Vitamin D3 supplementation in reducing leiomyoma-related symptoms and stabilizing uterine and leiomyoma volume.

Our study aimed to evaluate the effect of Vitamin D3 supplementation on leiomyoma-related symptoms, uterine and leiomyoma volume among women having symptomatic leiomyomata and Vitamin D3 hypovitaminosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The pilot, interventional, prospective study was carried out from November 2015 to April 2017. Women with symptomatic leiomyoma were subjected to serum 25(OH) vitamin D3 levels estimation. Thirty premenopausal women with minimum ultrasonic leiomyoma volume of 2 cm3 with Vitamin D3 insufficiency (20–30 ng/ml) or deficiency (<20 ng/ml) were recruited for the study. The exclusion criteria were the presence of pregnancy or lactation, genital tract malignancy, history of hormonal treatment in the past 3 months, endometrial hyperplasia, adnexal pathology, and patient necessitating early surgical intervention for uterine leiomyoma. Quantification of menstrual blood loss was done by pictorial blood loss assessment chart and severity of the symptoms graded according to the Visual Analog Scale.

Ultrasound evaluation (transabdominal or transvaginal) of uterine and leiomyoma volume was done by single observer using Logic P6 Pro Color Doppler (GE Ultrasound Korea Ltd.) machine. Viscosmi formula was used for the uterine volume, i.e., 4/3 π W/2 × L/2 × T/2, where W is uterine width on transverse section passing through the uterine fundus; L is uterine length, measured on sagittal section from internal cervical os to fundus. T is uterine thickness measured on sagittal section between the anterior and posterior walls.[12]

Assessment of leiomyoma volume was done by the formula 4/3 π abc, where abc represents radii of the sphere in three dimensions. In cases of multiple fibroids, total of all the leiomyoma volume was taken.

Vitamin D3 was made available from the hospital pharmacy, and all the participants received Vitamin D3 in doses of 60,000 IU per week for 8 weeks followed by 60,000 IU once every 2 weeks for maintenance therapy for another 8 weeks as per the Institute of Medicine guidelines.[13]

Participants were followed at 8 weeks and 16 weeks from the start of the supplementation. Leiomyoma-related symptoms, ultrasonic parameters, and hemoglobin were reassessed at every visit. Serum Vitamin D3 levels were repeated at 16 weeks after the start of supplementation. The side effects of therapy, i.e., nausea, vomiting, anorexia, pruritus, polyuria, and polydipsia were enquired.

During the follow-up period, nonhormonal treatment (tranexamic acid 500 mg and mefenamic acid 500 mg 1 tablet 8 hourly) was given as and when required while patients requiring hormonal treatment and surgical intervention were dropped from the study.

25(OH) Vitamin D3 assay was done by chemiluminescent immunoassay (Beckman Coulter Access 2 Immunoassay System) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Values were expressed in ng/ml.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was not done as this was an exploratory trial. A sample of 30 participants was chosen for the study group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical package (version 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were checked for normality before the statistical analysis. Normally distributed continuous variables over time were analyzed using the repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's post hoc testing. For nonparametric data, Friedman test was used, and further paired comparisons were done using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The correlation of Vitamin D levels with total leiomyoma volume was done by Spearman's correlation coefficient. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Informed consent

Institutional Ethics Committee Clearance was obtained. All the women signed informed consent for ultrasound execution; 25-hydroxy-cholecalciferol (25-OH-D3), serum levels determination; Vitamin D supplementation; and data collection at the time of enrollment (when the initial diagnosis of uterine fibroids was made).

RESULTS

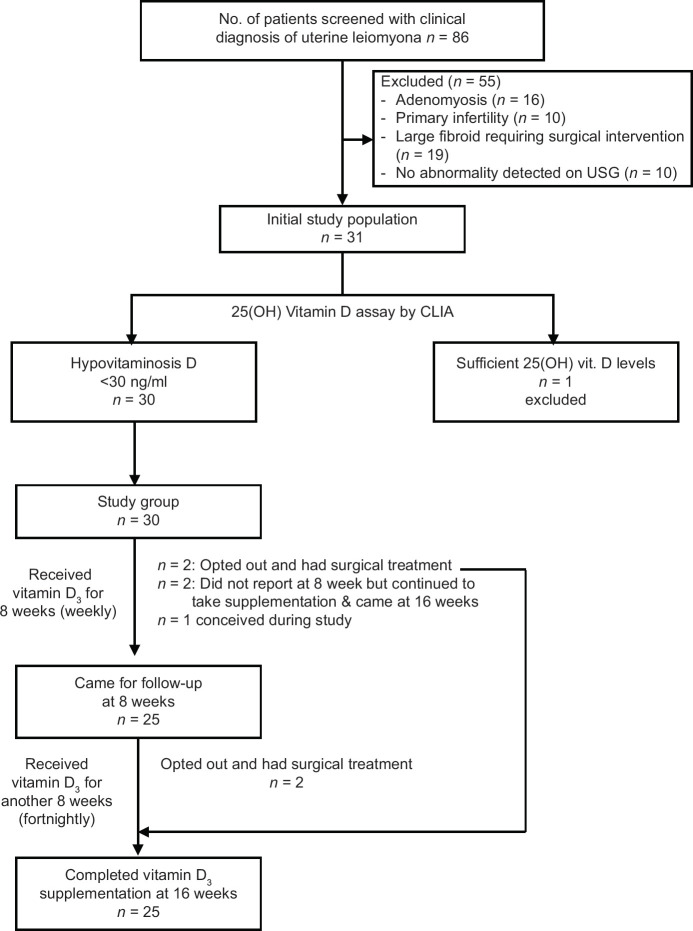

Thirty-one women who satisfied the inclusion criteria were subjected to S. 25(OH) Vitamin D3 levels estimation. Thirty out of 31 women (96.7%) were found to be having hypovitaminosis D. Out of 30 women on Vitamin D supplementation, 4 opted out and had surgical treatment and 1 woman was dropped from the study since she became pregnant. Twenty-five women completed the study, 2 did not report at 8 weeks due to personal reasons; however, all reported at 16 weeks follow-up [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Study flow chart

Pretherapy evaluation

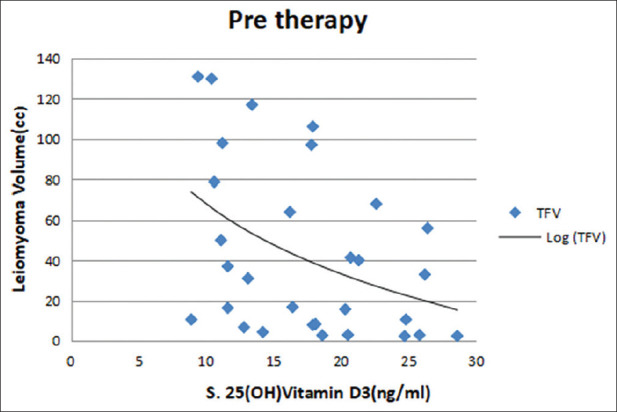

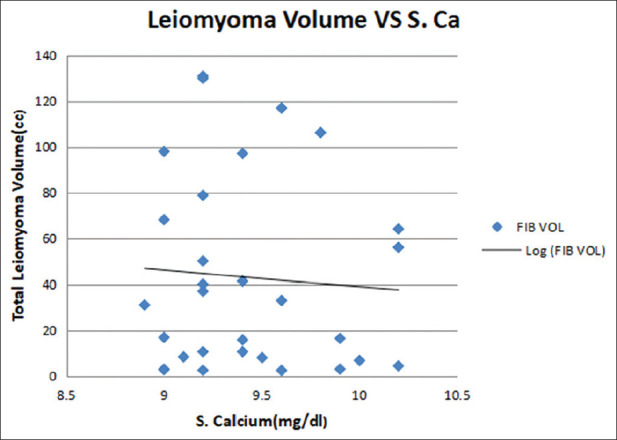

Maximum number of patients belonged to lower middle socioeconomic strata with a mean age of 37.16 ± 4.4 years. Majority of patients were multipara and had mean body mass index of 25.9 ± 4.6 kg/m2. The common symptoms were of heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea followed by low backache and pelvic pain. The mean menstrual blood loss was 139.46 ± 87.10 ml [Table 1]. Uterine size varied from 5 weeks (bulky) gravid uterus size to 12 weeks. Most of the women had 6 weeks uterine size on per vaginal examination. The mean uterine size of the women in the present study was 7.6 ± 2.2 weeks. Majority of women had single and intramural type of uterine fibroid. Ultrasonically measured mean uterine volume and leiomyoma volume were 148 ± 71 cc and 43 ± 45 cc, respectively [Table 2]. None of the patients had abnormal liver or kidney function test at the time of recruitment. Mean hemoglobin was <12 g% and mean 25(OH) Vitamin D3 level was 17.44 ± 5.82 ng/ml. Eleven patients presented with 25(OH) Vitamin D3 deficiency (<20 ng/ml) and 19 patients with insufficiency (<30 ng/ml). Mean S. Ca level was 9.4 ± 0.39 mg/dl [Table 2]. A significant negative correlation was observed between the baseline 25(OH) Vitamin D3 level and total leiomyoma volume (r = −0.434, P ≤ 0.001) [Figure 2]. No correlation emerged between calcium serum levels and the total volume of fibroids (r = −0.040, P = 0.835) [Figure 3].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

| Number of women (n=30), n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 37.16±4.4 |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Upper middle | 10 (33.3) |

| Lower middle | 14 (46.6) |

| Upper lower | 6 (20.0) |

| Parity (mean±SD) | 3.3±0.98 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean±SD) | 25.91±4.653 |

| Heavy menstrual bleeding | 24 (80) |

| Dysmenorrhea | 23 (76.66) |

| Pelvic pain | 14 (46.66) |

| Low backache | 18 (60.0) |

| Urinary frequency | 1 (3.33) |

| Dyspareunia | 4 (13.33) |

| Menstrual blood loss (ml) (mean±SD) | 139.46±87.10 |

| Uterine size on PV exam (weeks) (mean±SD) | 7.6±2.22 |

SD: Standard deviation, PV: Pelvic, BMI: Body mass index

Table 2.

Ultrasonic and biochemical characteristics of the participants

| Ultrasound characteristics | Number of women (n=30), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Leiomyoma type? | |

| Intramural | 27 (90) |

| Submucosal | 3 (10) |

| Subserous | 5 (16.7) |

| Number of fibroids | |

| 1 | 26 |

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 |

| Volume (mean±SD), volume (cm3) | |

| Uterine volume | 148.03±71.13 |

| Total leiomyoma volume | 043.09±45.71 |

| Largest leiomyoma volume | 040.76±39.72 |

| Biochemical parameters (mean±SD) | |

| Hemoglobin (g%) | 10.73±1.55 |

| Serum bilirubin (mg/dl) | 00.59±0.22 |

| SGOT (IU/L) | 27.53±5.66 |

| SGPT (IU/L) | 25.17±6.84 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 106.57±32.75 |

| Blood urea (mg/dl) | 20.28±4.65 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 00.60±0.14 |

| 25(OH)D3 (ng/ml) | |

| <20 ng/ml (n=11) | 17.44±5.82 |

| 20-30 ng/ml (n=19) | |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 09.42±0.39 |

SD: Standard deviation, SGOT: Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, SGPT: Serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase, ALP: Alkaline phosphatase

Figure 2.

Correlation between baseline 25(OH) Vitamin D3 and leiomyoma volume

Figure 3.

Correlation between S. Calcium and total leiomyoma volume (r = −0.040, P = 0.835)

Posttherapy evaluation

Significant percentage reduction was observed in mean pictorial blood loss, dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain and backache at 8 weeks posttherapy (27.68%, 29.41%, 25%, 34.6%, P = 0.004, <0.001, 0.001, 0.002) and at 16 weeks (29.89%, 44.12%, 35%, 50% P = 0.003, <0.001, 0.019, 0.002), respectively. Percentage reduction between 8 weeks of therapy and 16 weeks of therapy was not significant (2%, 14%, 10%, 15%; P = 1.0, 0.17, 0.98, 0.13, respectively) for all the four symptoms. Although the number of patients with dyspareunia and urinary symptoms was less, they did show significant improvement at 8 weeks and 16 weeks of therapy [Table 3].

Table 3.

Effect of Vitamin D supplementation on leiomyoma-related symptoms

| Duration of therapy | Number of women (n=25) | P from baseline (Friedman test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value ml (percentage change) | SD | ||

| Mean pictoral blood loss (cc) (weeks) | |||

| Baseline | 139.46 | 87.10 | |

| 8 | 100.85 (−27.68) | 62.67 | 0.004 (S) |

| 16 | 97.77 (−29.89) | 62.83 | 0.003 (S) |

| P (8-16) | 1.00 (NS) | ||

| Dysmenorrhea (weeks) | Percentage change (mean vas score) | SD | P from baseline (Friedman test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) |

| Baseline | 73.91 | 44.90 | |

| 8 | 52.17 (−29.41) | 35.29 | <0.001 (S) |

| 16 | 41.30 (−44.12) | 37.39 | <0.001 (S) |

| P (8-16) | 0.170 (NS) | ||

| Pelvic pain (weeks) | |||

| Baseline | 43.48 | 50.69 | |

| 8 | 32.61 (−25) | 38.02 | 0.001 (S) |

| 16 | 28.26 (−35) | 33.97 | 0.019 (S) |

| P (8-16) | 0.985 (NS) | ||

| Backache (weeks) | |||

| Baseline | 56.52 | 50.69 | |

| 8 | 36.96 (−34.6) | 36.83 | 0.002 (S) |

| 16 | 28.26 (−50.0) | 33.97 | 0.002 (S) |

| P (8-16) | 0.128 (NS) | ||

| Dyspareunia (weeks) | |||

| Baseline | 13.04 | 34.44 | |

| 8 | 9.78 (−25) | 25.83 | 0.249 (NS) |

| 16 | 9.78 (−25) | 25.83 | 0.249 (NS) |

?Only one patient had urinary frequency which was improved after therapy. SD: Standard deviation, NS: Not significant, S: Significant

There was no change in location and number fibroids at end of the treatment. Percentage decrease in mean uterine volume and mean leiomyoma volume at 8 weeks (6.9%, 11.8% P = 1.00, 0.558, respectively) and 16 weeks posttherapy (8.3%, 11.6% P = 1.00, 0.906, respectively) was not significant [Table 4].

Table 4.

Effect of Vitamin D therapy on uterine and leiomyoma volume

| Duration of therapy | Number of women n=25 | P from baseline (Friedman test, Wilcoxon signed rank test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value (cc) (percentage change) | SD | ||

| Mean uterine volume (cc) (weeks) | |||

| Baseline | 148.03 | 71.13 | |

| 8 | 141.13 (−4.7) | 56.72 | 1.00 (NS) |

| 16 | 139.70 (−6.1) | 66.42 | 1.00 (NS) |

| P (8-16) (Friedman test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) | 1.00 (NS) | ||

| Mean leiomyoma volume (cc) (weeks) | |||

| Baseline | 43.09 | 45.71 | |

| 8 | 38.00 (−11.8) | 39.85 | 0.558 (NS) |

| 16 | 38.08 (−11.6) | 40.28 | 0.906 (NS) |

| P (8-16) (Friedman test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) | 1.00 (NS) | ||

SD: Standard deviation, NS: Not significant

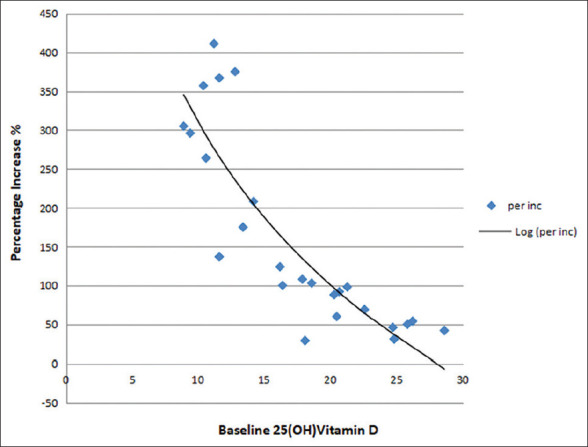

There was a general sense of well-being in many patients after 16 weeks of Vitamin D supplementation. It was observed that 48% of patients had feeling of better well-being, 48% had no improvement, and 4% felt unwell compared to pretherapy period. There was no significant change in mean hemoglobin levels at 8 weeks and 16 weeks posttherapy. Mean 25(OH) Vitamin D level was increased from 17.44 ± 5.82 ng/ml to 39.38 ± 8.22 ng/ml after 16 weeks of Vitamin D3 supplementation. This change was highly significant (P ≤ 0.001) [Table 5]. Negative correlation was observed between baseline S. 25(OH) Vitamin D3 values and the increase in the serum levels with therapy [Figure 4]. No side effects such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weakness, pruritis, polyuria, and polydipsia were noticed at 8 weeks and 16 weeks.

Table 5.

Effect of Vitamin D supplementation on hemoglobin and Vitamin D serum levels

| Duration of therapy | Number of women (n=25) | P from baseline (repeated measures analysis of variance) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value | SD | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) (weeks) | |||

| Baseline | 10.65 | 1.52 | |

| 8 | 10.65 | 1.39 | 1.00 (NS) |

| 16 | 10.52 | 1.29 | 1.00 (NS) |

| P (8-16) (repeated measures analysis of variance) | 1.00 (NS) | ||

| Vitamin D3 levels (ng/di) (weeks), mean value (ng/ml) | |||

| Baseline | 17.44 | 5.82 | |

| 16 | 39.38 | 8.22 | <0.001 |

SD: Standard deviation, NS: Not significant

Figure 4.

Correlation between baseline 25(OH) Vitamin D3 levels and increase (%) in 25(OH) Vitamin D3 levels posttherapy

DISCUSSION

It has been found that a large proportion of adults are suffering with low serum Vitamin D levels.[1,2] Studies conducted among adults aged 18–40 years of age documented that 83% of the population had Vitamin D deficiency – 25%, 33%, and 25% had mild, moderate, and severe deficiency, respectively.[3,4,5,6]

In our study, 96.7% women with leiomyoma were found to be having hypovitaminosis D which favors the view of high prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in India, i.e., 50–90% and more so in the patients of leiomyoma.[4,14]

Mean 25(OH) Vitamin D3 level was 17.44 ng/ml (Vitamin D deficiency). 36.66% patients had deficiency (<20 ng/ml) and 63.33% had insufficiency (<30 ng/ml). A significant negative correlation was observed between the baseline 25(OH) Vitamin D3 and total leiomyoma volume (r = −0.434, P ≤ 0.001). Previous studies also reported a similar negative correlation between 25(OH) Vitamin D3 and total leiomyoma volume.[15] In a cross-sectional, observational study by Sabry et al., a statistically significant inverse correlation between serum 25(OH) Vitamin D levels and total fibroid volume in black participants (r = −0.42; P = 0.001) was found. Recent observational study by Ciavattini et al. also observed a negative correlation between the baseline 25-OH-D3 concentration and both the volume of the largest fibroid (r = −0.18, P = 0.01) and the total volume of fibroids (r = −0.19, P = 0.01).[11] The present study and the existing literature supports the view that Vitamin D deficiency could be a possible risk factor for the occurrence of uterine leiomyoma. However, comparison of the Vitamin D3 level of our population with healthy controls was not done.

Mean serum calcium level was normal 9.4 mg/dl, and there was no significant correlation between serum calcium level and the total leiomyoma volume. This is consistent with the study by Ciavattini et al.[11]

In the present study, Vitamin D supplementation decreased the mean menstrual blood loss significantly by 29.89% at 16 weeks and significant decrease in blood loss was observed as early as 8 weeks, i.e., 27.68%. From 8 to 16 weeks of therapy, there was slight decrease in the blood loss which was not significant (P = 0.003). This shows that Vitamin D supplementation significantly reduces menstrual blood loss which is achieved by 8 weeks.

There was a similar response for severity of dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, and backache which decreased significantly by 44%, 35%, and 50%, respectively, at the end of therapy (16 weeks), and this decrease was evident as early as 8 weeks. There are no other studies in literature which explored the effect of Vitamin D therapy on leiomyoma-related symptoms.

High incidence of backache in the present study (60% of the women) can be explained by Vitamin D deficiency because all the patients had small burden uterine fibroids (i.e., <12 weeks uterine size) which is not commonly associated with backache. Vitamin D therapy reduced the backache by 50% which was statistically significant.

On monitoring the response to Vitamin D therapy by ultrasonic assessment, it was observed that there was no occurrence of new fibroids or change in the location of fibroids after 16 weeks of Vitamin D supplementation. Ciavattini et al. in their study on Vitamin D supplementation for small burden fibroids did not report any change in the location and number of leiomyomas.[11]

On ultrasonographic measurement after 16 weeks of Vitamin D therapy, there was 6% reduction in mean uterine volume and 11% in total leiomyoma volume which was not significant. And also, no significant difference in volumes emerged between 8 weeks and 16 weeks of therapy (P = 1.00) [Table 5].

The only study published so far by Ciavattini et al. is comparable to our observations and revealed that on Vitamin D supplementation for 1 year, leiomyoma volume and diameter remained static in the study group (P = 0.63); however, in the control group which did not receive Vitamin D therapy, there was progression to extensive disease.[11] From above observation, it is concluded that leiomyoma volume remained static at 8 weeks and 16 weeks of Vitamin D supplementation. However, drastic response was not seen in humans as compared to in vivo study on female Eker rats with leiomyoma in which Halder et al. demonstrated that Vitamin D3 resulted in 75% reduction in leiomyoma tumor size over a period of 4 weeks.[10] Leiomyomas are monoclonal tumors of the smooth muscle cells of the myometrium and consist of large amounts of extracellular matrix. Vitamin D3 acts by the suppression of cellular growth and proliferation-related genes, antiapoptotic genes, and estrogen and progesterone receptors.[4]

There was no improvement in hemoglobin although menstrual loss decreased significantly from pretherapy level; however, this finding suggests that Vitamin D supplementation inhibits decline in hemoglobin levels during therapy by significantly decreasing mean menstrual blood loss.

In the present study, patients had the feeling of general well-being which can be contributed to the correction of Vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency along with the reduction in severity of leiomyoma-related symptoms.

After 16 weeks of Vitamin D3 supplementation, serum 25(OH) Vitamin D3 was significantly higher compared with the baseline level. It was observed that the efficacy of Vitamin D3 supplementation was related to the baseline Vitamin D serum levels, with higher responses in women with lower levels at the time of initial diagnosis which was also noted by Ciavattini et al.[11] Whether this has any bearing on the response of leiomyoma to Vitamin D replacement therapy still remains a question.

This study although done on the small number of women yet clearly indicates that 25(OH) Vitamin D3 replacement therapy for 16 weeks is efficacious in reducing leiomyoma-related symptoms and stabilizing uterine and leiomyoma volume. Vitamin D deficiency is very common in leiomyoma patients in the present study (96%), routine supplementation of Vitamin D may be considered to all the patients with uterine leiomyoma in our country or all women with leiomyoma should get Vitamin D3 levels estimated. However, the effects of Vitamin D supplementation were slow, and hence, other suitable medicines such as tranexamic or Mefenamic acid for abnormal uterine bleeding, ulipristal acetate, or mifepristone for reducing size of myoma can also be considered.

Limitations of the study

The number of cases is small, only 30 women were enrolled for the study; however, large trials are required to further validate the findings

Power of the study is weak as no comparison was done with healthy controls.

CONCLUSION

Supplementation of 16 weeks of 25(OH) Vitamin D3 is efficacious, acceptable, and safe in symptomatic uterine leiomyoma, and it can emerge as a novel oral noninvasive therapeutic agent for this common disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Okolo S. Incidence, aetiology and epidemiology of uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:571–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabry M, Al-Hendy A. Innovative oral treatments of uterine leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:943635. doi: 10.1155/2012/943635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rackow BW, Arici A. Options for medical treatment of myomas. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:97–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciebiera M, Włodarczyk M, Ciebiera M, Zaręba K, Łukaszuk K, Jakiel G. Vitamin D and uterine fibroids-review of the literature and novel concepts. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2051. doi: 10.3390/ijms19072051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabry M, Halder SK, Allah AS, Roshdy E, Rajaratnam V, Al-Hendy A. Serum vitamin D3 level inversely correlates with uterine fibroid volume in different ethnic groups: A cross-sectional observational study. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:93–100. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S38800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baird DD, Hill MC, Schectman JM, Hollis BW. Vitamin d and the risk of uterine fibroids. Epidemiology. 2013;24:447–53. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828acca0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paffoni A, Somigliana E, Vigano’ P, Benaglia L, Cardellicchio L, Pagliardini L, et al. Vitamin D status in women with uterine leiomyomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1374–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halder SK, Goodwin JS, Al-Hendy A. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces TGF-beta3-induced fibrosis-related gene expression in human uterine leiomyoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E754–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halder SK, Osteen KG, Al-Hendy A. Vitamin D3 inhibits expression and activities of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 in human uterine fibroid cells. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2407–16. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halder SK, Sharan C, Al-Hendy A. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatment shrinks uterine leiomyoma tumors in the Eker rat model. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:116. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.098145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciavattini A, Delli Carpini G, Serri M, Vignini A, Sabbatinelli J, Tozzi A, et al. Hypovitaminosis D and “small burden” uterine fibroids: Opportunity for a vitamin D supplementation. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e5698. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagaria M, Suneja A, Vaid NB, Guleria K, Mishra K. Low-dose mifepristone in treatment of uterine leiomyoma: A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehlawat U, Singh P, Pande S. Current status of vitamin D deficiency in India: A review. Inn Pharm Pharmacother. 2014;2:328–35. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajhashemi M, Ansari M, Haghollahi F, Eslami B. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on the size of uterine leiomyoma in women with vitamin D deficiency. Caspian J Intern Med. 2019;10:125–31. doi: 10.22088/cjim.10.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]