Abstract

Tendinopathies are common causes of pain around the elbow resulting in significant functional impairment in athletes or the working-age population. Patients complain of a gradual onset pain with or without any specific trauma. Tissue histology shows chronic fibroblast and vascular proliferation, with a disorganized collagen pattern and absence of inflammatory mediators. Currently, numerous treatment options are described, but many of these are only supported by a heterogenous evidence base. Thus, management guidelines are difficult to define. Surgery is mostly indicated in selected cases that have failed non-operative management. This article reviews the pathophysiology and natural history of lateral and medial elbow tendinopathies, as well as distal biceps and triceps tendinopathies, and their current treatment options.

Keywords: Tennis Elbow, Golfer's Elbow, Tendinopathy triceps, Tendinitis Biceps

1. Introduction

Tendon disorders around the elbow are responsible for considerable morbidity in sport and in the workplace. However, their diagnosis and treatment has remained contentious due to their complex anatomy and pathogenesis. Symptoms often have an insidious onset without any clear precipitating event but may follow an injury or repetitive activity above the endurance limit. Although several therapeutic options are routinely used, there is a deficiency of randomised controlled trials which can assist in evidence-based management. This review article will attempt to identify the natural history, pathogenesis, diagnostic methods and optimal treatment options in the tendinopathies around the elbow including lateral and medial epicondylitis, distal biceps and distal triceps tendinopathy based on the current evidence.

2. Lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow)

2.1. Definition and epidemiology

The commonest cause of lateral elbow pain is Lateral Epicondylitis (LE) (United Kingdom incidence 1–3%).1 It is typically seen in a middle-aged population (30–65 years), with an equal gender distribution.1 It can develop from a variety of sports and work-related activities that require forceful or repetitive use of forearm extensors. The commonly recognised risk factors are smoking, obesity and diabetes.2

2.2. Pathophysiology and anatomy

Lateral epicondylitis usually arises from any activity that requires overuse of the proximal origins of the wrist common extensors2,3 resulting in tendon structure disruption and cell matrix degeneration, which in turn causes degenerative changes in the origin of common extensor origin at the humeral lateral epicondyle.3 Tendinosis is not entirely understood, but is a degenerative process with lack of inflammatory cells.3 After prolonged tendon damage, an increased number chronic fibroblast and vascular proliferation, with disorganized collagen is found histologically (angio-fibroblastic hyperplasia). This leads to structural failure and may result in partial or sometimes complete tear of tendon.4 The most commonly affected tendon is the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) as described by Cyriax.5 Its tendon wraps around the convexcity of the lateral epicondyle, therefore exposed to repetitive tensile stresses. The extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendon can be affected in one-third of the cases.1,2 Concomitant radial tunnel syndrome is found in 5% of patients with LE.6

2.3. Diagnosis

LE is predominantly diagnosed by history and examination. The most common complaint is pain around the lateral epicondyle (within 5–15 mm). Symptoms develop slowly, and are troublesome after activities involving repeated wrist extension. The pain, of variable intensity, often radiates distally along the line of the forearm extensor muscles. Physical examination is unlikely to reveal any obvious soft tissue changes and swelling, in contrast with its counterpart, medial epicondylitis. Nevertheless, a diffuse pattern of tenderness may be elicited. In the majority of cases, active and passive movements are commonly maintained within normal range. However, terminal extension can be limited when the forearm is pronated, particularly in cases with severe symptoms.7

The following provocative tests can be used to diagnose LE:

-

A.

Cozen's test: The elbow is kept extended, and resisted wrist extension causes pain around the common extensor origin,targeting the ECRB tendon7 (Fig. 1).

-

B.

Maudsley's test: Pain around the EDC tendon occurs when resisting extension of the middle finger.7

-

C.

Mill's test: The wrist and elbow is kept extended.Tenderness is felt on the lateral epicondyle when pronating the forearm of the patient.7

-

D.

‘Chair test’: The arm is kept in extension and the shoulder is flexed to 60°. The patient ‘s pain is exacerbated when trying to lift a chair.7

Fig. 1.

Cozen's Test: The elbow is extended. Wrist extension against resistance causes pain. At the common extensor origin.

Saroja et al. measured the diagnostic accuracy of these provocation tests. The sensitivity for Cozen's test was 84% and the sensitivities of the Maudsley and Mill's tests were 88% and 53%, respectively. The specificity for Cozen's test was almost 100%.7

The other important causes to consider when evaluating a patient with lateral elbow pain are:

-

1.

Infection, inflammatory or degenerative conditions (e.g. radio-capitellar joint).

-

2.

Isolated or concomitant posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) compression also called radial tunnel syndrome. This nerve entrapment may replicate symptoms mimicking LE. However the provocation tests are usually negative.

-

3.

Cervical radiculopathy with radiating neuropathic pain.

-

4.

Elbow overuse due to ipsilateral shoulder pathology (i.e., frozen shoulder)

-

5.

Synovial Plica. In articular development, the plica is the remnant of embryonic septae.8 Chronic overloading or injury of the synovium can result in thickening of the plica which may impinge between the articular surfaces. Presumably, similar mechanisms of injury in both synovial plica and lateral epicondylitis results in the frequent occurrence of plica in patients with LE. The synovial plica can cause “clicking” on terminal extension of the elbow and supination of the forearm supination.8 However, plica occuring without these symtoms and signs leadto difficulty in discriminating between symptomatic plica and LE in the outpatient clinic setting.

Although clinical examination is often sufficient to diagnose LE, further imaging and laboratory tests can help to confirm the diagnosis, grade the injury, and guide treatment. These include:

-

1.

Laboratory indices such as inflammatory markers. These can help differentiate between LE and inflammatory condition or infection.

-

2.Radiological assessment:

-

a.Plain radiographs can be used to exclude any osseous abnormality, soft tissue calcification, degenerative changes or loose bodies.

-

b.Ultrasound imaging can usefully identify hypoechogenic foci in the tendons suggesting intra-substance degeneration, tendon tears and calcification, or minor bony irregularity. Furthermore, ultrasound can also detect neovascularisation and bony irregularity.

-

c.Despite easy availability and cost-effectiveness of ultrasound, MRI can be considered as a more reliable investigation as it can show other intra-articular pathologies and minimise the intra-operator variability associated with ultrasound. Savnik et al.,9 found MRI changes (different signal intensity within ECRB attachment) in the majority of a small cohort. Interestingly, they reported no correlation between the MRI findings and patient reported symptoms. In general, the MRI changes may mpersist despite clinical resolution of symptoms.

-

d.A study Comparing10 CT arthrography with MRI with arthroscopic findings as gold standard found CT arthrography more sensitive when compared with MRI scans for demonstrating capsular tears on the deep surface of ECRB (85% vs. 64.5%).

-

a.

Nonetheless, abnormalities on imaging do not always correlate with clinical symptoms and hence are not a substitute for good clinical acumen, as imaging findings sometimes could just be incidental findings.

2.4. Treatment

2.4.1. Non operative

Lateral epicondylitis, does not always require treatment. It is usually a self-limiting condition, with almost 89% of patients recovering by 1 year.11 The aims of treatment, if required, are pain control, preservation of movement, restoration of function, and preventing the worsening of symptoms.11

Non-surgical management includes rest or avoiding any aggravating activities, application of ice or heat, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), bracing and physiotherapy.11 Compared to a ‘wait and see’ policy, physiotherapy shows improvement in pain12. Epicondylar braces could reduce forces in the forearm extensors and show improved pain relief and grip strength. However, a meta-analysis did not show superiority of one brace over the others.13

Alternative non-operative options include corticosteroid injectiosn with further eccentric exercises. However, increasingly there is evidence that corticosteroids produce inferior long-term results and can cause complications.14,15 An RCT compared steroid injections, physiotherapy and a policy of ‘‘wait-and-watch’‘12 in the management of LE. Corticosteroid injections resulted in significantly superior outcomes than the alternative choices at 6 weeks. However, the impact of physical therapy was far better than the other treatment options at 52 weeks follow-up. Similarly, in primary care, Hay et al. showed enhanced pain relief in LE using corticosteroid injections when compared with NSAIDs and placebo at 4 weeks, but they showed no significant difference between these treatment methods at and after 12 months.14 Coombes et al.15 investigated the effectiveness of corticosteroid injections, placebo injections alone or combined with multimodal physiotherapy at 1 year. In this RCT the corticosteroid injections produced significantly worse outcomes at 1 year (lower complete recovery and greater recurrence). The physiotherapy did not show any significant difference compared to those who had no physiotherapy. According to them corticosteroid injections worsened the long-term results and in the long-term physiotherapy was not effective.16 In addition, corticosteroids can lead to skin depigmentation, atrophy and muscle wasting, resulting in increased prominence of the lateral epicondyle.

Injections are usually given using a single-injection technique but can also be given using a “peppering technique”. The latter requires dry needling in the degenerative myxoid tissue to generate channels and stimulate local blood flow.

Other non-surgical treatments include platelet rich plasma (PRP), autologous blood injections iontophoresis, botulinum-toxin, laser therapy, acupuncture, extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) prolotherapy.16, 17, 18 Many randomised controlled trials are published in these techniques. Sims et al.17 reviewed these therapies and found no difference in various treatments. Recently, stem cell therapy is being researched for treatment of LE. Although it shows promise only pilot studies are available to date.18 Local injection of PRP is another recent development which has gained popularity. The plasma fraction of autologous blood which contains concentrated growth factors and cytokines works by locally recruiting macrophages and progenitor cells, which stimulates tissue regeneration. However, this is dose dependent and varies between individuals. Various RCTs show superiority of PRP over autologous blood and corticosteroids.16,18 However, the small number of available studies have significant variation in the way the PRP is prepared and activated hence conclusions on the efficacy of PRP remains debateable.

2.5. Operative treatment

The majority of all lateral epicondylitis can be successfully treated nonoperatively. The remainder (4–25%) are often challenging to manage and some could be considered as candidates for surgery. Surgery is indicated when non-operative measures have failed within 6–12 months. Different surgical methods include open, percutaneous or arthroscopic surgical release. Many variations of open surgical technique exist. As a standard approach, after a longitudinal incision on the lateral epicondyle, the origin of the common extensor tendon is exposed. Some surgeons divide the ERCB tendon, whereas others prefer to lengthen or repair it. Some reports mention decortication or drilling of the epicondyle.19 The technique described by Nirschl and Pettrone19 is commonly used. It comprises excising the degenerative area from the ECRB, decorticating the lateral epicondyle area or drilling it, and anatomical repair of ECRL. They reported 98% of their cohort (n = 88) improved following the procedure. Calvert et al.20 divided the common extensor origin at the lateral epicondyle. Their report on 42 elbows undergoing the simple lateral release showed satisfactory outcomes in 80% of patients. Verhaar et al.21 showed results of lateral release in 63 patients and reported 89% good to excellent results at 5 years.

Open surgery, while successful, often carries risks of complications like infection, haematoma formation, nerve damage and injury to lateral collateral ligaments. Compromising the lateral elbow stability is a major complication resulting in 25% of failed open release.22 Revision surgery can completely uncover the radio-capitellar joint. Additionally, damaging the capsule and synovial lining, accelerating the degenerative changes. Baumgard and Schwarts23 described a percutaneous release with wrist in flexion and forearm in pronation to create maximum tension within common extensor origins. Using a stab incision, the ECRB can be released. They reported excellent outcome (complete relief of symptoms) at three-years.

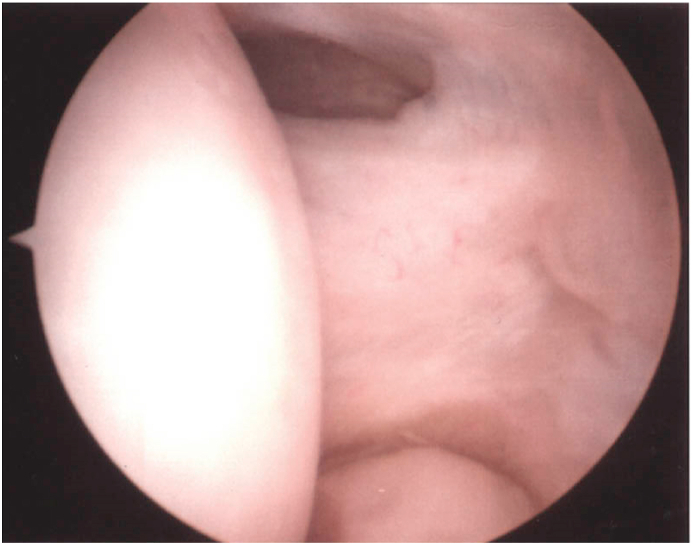

Using an arthroscopic technique, Baker and Baker24 reported good outcomes of 87% at an average follow-up of 130 months in 42 elbows who underwent arthroscopic debridement. The arthroscopic technique is useful in diagnosing and simultaneously treating co-existing intra-articular pathology. In addition, it limits tissue damage and allows good visualisation (Fig. 2) including the under-surface of the ECRB tendon. The technique can take longer than an open procedure, has a long learning curve and there is a risk of nerve injury. Recently, a systematic review25 compared open, arthroscopic and percutaneous techniques. They found thirty reports including 848 open procedures, 578 were arthroscopic techniques, and 178 involved percutaneous procedures. They concluded that open and arthroscopic procedures may have better outcomes than percutaneous techniques. In addition, better pain relief was reported with arthroscopic and percutaneous releases. However, the overall risks were similar regardless of techniques used. Patient should be informed of potential risk of infections more likely in open surgery. Overall, there is a lack of good quality evidence to draw a meaningful conclusion on the superiority of one operative technique over another.

Fig. 2.

Nirschal lesion: seen at the 12 O'clock position.

2.6. Medial epicondylitis (ME) (Golfer's elbow)

2.6.1. Epidemiology

ME affects the common flexor origin at the medial epicondyle of the humerus. Compared to LE, the prevalence of medial epicondylitis has been reported to be as high as 4% in the working population. It usually affects people aged 40–60 years, and more commonly affects women than men. Repetitive movements, smoking, obesity are Poor prognostic factors.26

2.6.2. Pathophysiology and anatomy

The most commonly involved muscles are flexor carpi radialis (FCR) and pronator teres (PT) at their humeral origin at the medial epicondyle.

Valgus stress combined with repetitive eccentric and concentric forces (mainly during throwing movements), these tendons are exposed to supra-physiological valgus tensile stress subjecting them to microtrauma, leading to medial epicondylitis.

Microscopically, reactive fibrous connective tissue with varying degree of inflammation have been identified similar to lateral epicondylitis.27 Studies show that during the acceleration phase of throwing, significant activity is seen in the FCR and PT due to increased valgus stress.

It is important to remember that ME may be associated with cubital tunnel syndrome and/or medial collateral ligament injury. The latter play a cardinal role in resisting valgus stress as a primary stabiliser of the elbow. Valgus stress on the ulnar nerve may result in inflammation and entrapment of the nerve.

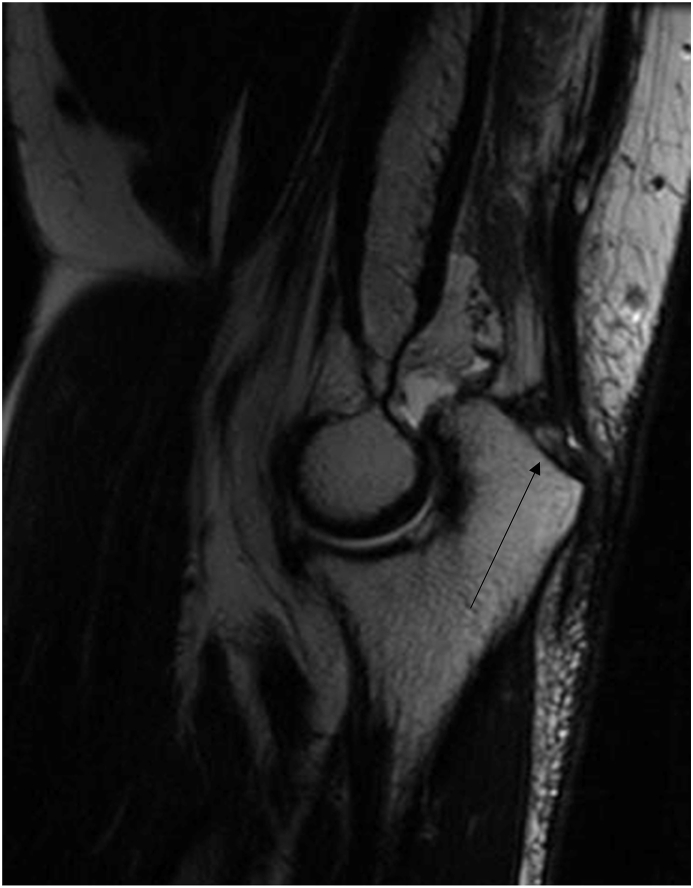

2.6.3. Diagnosis

It presents with gradually increasing pain in the elbow on the medial side. Localised swelling may be noted. Pain is reproduced by flexing the wrist against resistance in a pronated forearm. There is tenderness within 1 cm anterior to 1 cm posterior aspect of the medial epicondyle (over the PT and FCR). Other concomitant pathologies like a simultaneous ulnar nerve entrapment or elbow instability may co-exist. Radiographs can be normal, although in some cases an area calcification is found at the medial epicondyle(27). Nerve conduction studies can be helpful to differentiate ulnar nerve symptoms from ME. MRI sometimes shows tears in the common flexor origin and increased signals and is an useful tool (Fig. 3). Diagnostic accuracy of Ultrasound is operator dependent but it can demonstrate hypoechoic area around the medial epicondyle.

Fig. 3.

MRI: Medial epicondilitis: Increased signal over medial epicondyle (bony and peri-tendinous (common flexor origins) oedema). (marked with arrow).

2.6.4. Treatment

Treatment strategies are essentially similar to its lateral counterpart. Nevertheless, the current literature lacks well-designed, prospective, randomised, controlled trials to assess different treatment methods, with no good quantitative or qualitative reviews.

In general, conservative treatment remains the basis of initial treatment in the acute phase of the tendinopathy, consisting of application of ice, rest, physiotherapy, activity modification, bracing and NSAIDs. In addition, corticosteroid injections can be considered if the initial management fails or symptoms persist, but this has only shown to alleviate symptoms for a short period. An RCT compared corticosteroid and local anaesthetic injections in 60 elbows with isolated ME and showed better pain relief at 6 weeks in favour of corticosteroids. However, its effectiveness was similar to local anaesthetic at 3 months and beyond.3 On the other hand, inherent risks such as skin and fat atrophy should not be overlooked. Furthermore, autologous blood injections with dry needling under ultrasound is showing promising results in pain relief and improved function.28 Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has also shown generally unfavourable results with one study demonstrating improvement in only a third of patients.29

Overall, symptoms may relapse in 10–15% of patients. They can then be considered as candidates for surgical treatment.30 There is limited evidence for any one surgical method. However, the principal surgical management for medial epicondylitis remains the same as the lateral epicondylitis with open surgery as the mainstay of treatment. It involves excision of the degenerative part of the tendon to enhance vascularity, repair of any partial tears or resultant defects and then reattachment of elevated tendon origin.

A popular technique consists of an incision over the medial epicondyle protecting the ulnar nerve and without damaging the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which traverses superficially over the cubital tunnel within the adipose layer. The common flexor origin can either be incised longitudinally or transversely and released from its origin and the pathological tissue excised.

Based on current evidence, most surgeons use a “resection and repair” approach. Good to excellent results were reported by Vangsness and Jobe in 97% of their cohort after an average 6-year follow-up.27 Involvement of ulnar nerve affects the global outcome. Kurvers and Verhaar30 reported the outcome of 40 patients with ME who had open surgery without reattaching the common flexor origin. Co-existent ulnar nerve entrapment was identified in 60% of cases. Patients were assessed within 44 months follow-up. The overall subjective outcome was less favourable in patients who had coexistent ulnar nerve pathology (p < 0.05). Gabel et al.31 published that the ulnar nerve involvement and its severity can affect the surgical outcomes following reattachment of the flexor origin. In their cohort of 30 cases, 16 also had concomitant ulnar nerve symptoms. The majority (87%) reported good to excellent results after the release of common flexor origin and transposition of ulnar nerve. Recently, Speech et al.32 reported their study on 884 cases referred for electro-neurophysiological tests for ulnar nerve symptoms. Their study showed no correlation between positive test and medial elbow pain. They concluded that medial sided elbow joint pain is not diagnostic of ulnar neuropathy. However, the prevalence of associated medial epicondylitis was not well described/reported.

There is not much data on the arthroscopic treatment of ME. One recent retrospective study of 7 patients undergoing arthroscopic debridement of the common flexor origin exhibited good outcomes and the procedure was deemed safe, although this was a small case series.33 Some authors have raised concerns that the ulnar nerves close proximity poses risks which outweighs any significant benefits.

3. Distal biceps tendinopathy

3.1. Definition and epidemiology

Distal biceps tendinopathy is relatively rare. The literature consists of case reports and retrospective studies.34 Incidence of Complete distal biceps rupture is about 1.2/100,000, with almost 8-fold increased risk in smokers.35 Over 80% of cases are males, aged between 50 and 60 years.36 The natural history is unknown.

3.2. Anatomy and pathophysiology

The terminal tendon of biceps is flat arising about 7 cm proximal to the anterior elbow crease and travels laterally through the cubital fossa inserting onto the most medial aspect of the radial tuberosity.37 It rotates externally by about 90°,. It attaches via a footprint averaging 2.1 cm long and 0.7 cm wide.37 In addition to being the main supinator, biceps also helps in flexion of the elbow with the forearm supinated. It is an effective supinator in a flexed elbow. It is not as effective a flexor in mid-prone or a pronated forearm. Little has been reported on the pathological process of distal biceps tendinopathy. It is possibly due angio-fibroblastic hyperplasia. The most vulnerable anatomical location is typically its radial tuberosity insertion38, proximal to the osseo-tendinous junction, as this area is a hypovascular zone.

3.3. Diagnosis

Distal biceps tendinopathy or partial tear remains a diagnostic challenge in contrast to a complete rupture. The majority of patients report an injury that initiates their pain, or develop progressive symptoms which include anterior elbow pain, weakness associated with pain on forearm supination and elbow flexion.39, 40 On clinical assessment, tendon integrity feels intact but tender.39 Resisted supination exacerbates the pain. Compared to the other side supination is weak. Occasionally, reduction in movement due to pain is seen, mainly the last few degrees of extension.40 It is clinically crucial to differentiate a partial from a complete tear. Luokkala et al., retrospectively reviewed 234 consecutive distal biceps rupture and found the sensitivity for ‘hook test’ to be around 83% in complete tears and 78% in all tears and. Unsurprisingly, the sensitivity was lower in partial tendon tear (30%). They concluded a negative test cannot rule out a rupture.41 Shim and Strauch described a new test for the distal biceps tendon utilising the rotational anatomy of the radius for partial tears.42 The elbow is kept flexed at about 90° and the forearm is supinated and pronated passively the clinician firmly palpates for the radial tuberosity dorsally. The tuberosity is palpable only in full pronation and if tender indicates a positive test (TILT sign) (Fig. 4). The radial tuberosity is not felt in supination. They report that the test was 100% sensitive, however no other study has yet assessed its accuracy.

Fig. 4.

TILT sign: For distal biceps tendinitis.

Plain radiography has limited role in diagnosis, but MRI and ultrasound (US) evaluation remain the investigation of choice. Despite its cost effectiveness, availability and dynamic assessment of tendon and its insertion, reliability of US remains less than MRI. The orientation of the distal biceps tendon can make scanning a bit difficult. Chew and Giuffre36 described a position for a better view of the tendon on MRI. In prone position the arm is overhead. The elbow is flexed, forearm is supinated and shoulder is abducted, making the thumb pointing superiorly (FABS position). This position minimizes tendons rotation and obliquity, giving a “true” view. Partial tears demonstrate abnormal contour and intra-tendinous signal. Complete tears will show retraction if the bicipital aponeurosis is torn.

3.4. Treatment

The optimal treatment for partial tears and tendinopathy of distal biceps remains controversial. Like other tendinopathies, it seems reasonable to consider non-operative pathway as the initial step. However, there is paucity of reports with long-term outcomes of non-operative management, and to define the natural history. The major complication of non-operative management is the conversion of partial tear to a complete tear. Out of 4 patients Durr et al. published good outcomes in 3 cases with partial tear confirmed on MRI, following bracing or immobilisation for a duration of 2 weeks, local anaesthetic injection, NSAIDS and physical therapy.34 In contrast others have reported poor outcome in patients undergoing conservative management as they subsequently developed a complete tear.

It is important to Quantify the partial tear. Current evidence suggests considering non-operative management when tears are less than 50% of the tendon's insertion.34 Subsequently, tears involving more than 50% of tendon are likely to need debridement and repair or re-attachment using a standard open approach.38 There are variable surgical techniques described to date, and these rely largely upon case reports or small case series. Techniques include a single-incision (either anteriorly or posteriorly) or a two-incision approach.

Bourne and Morrey43 introduced the operative management of atraumatic distal biceps tendon partial tear, reporting the outcomes of three patients. Of these, two underwent a 2-incision technique to have their distal biceps partial tear released, debrided and re-attached, and one patient had only re-attachment without release and debridement. The latter showed an inferior result and required revision surgery. Vardakas et al.38 reviewed 7 cases of partial tear which underwent distal biceps release and reattachment via single incision anteriorly. The authors reported good outcomes in all cases with no complications noted. Similarly, Dallaero and Mallon40 reported uniformly excellent outcomes in 7 cases using the same technique. However, two patients reported neurapraxia of lateral cutaneous nerve of forearm, and 6 patients lost their terminal elbow extension by approximately 9°. Frazier et al.39 published 17 cases with partial tears who underwent surgical repair of surgeon's choice, after failure of non-operative management. The majority of surgeons used single anterior incision (n = 12). The tendon stump was reattached over the radial tuberosity using anchors. A patient had a failure (partial re-tear) at 4 years and another patient developed heterotopic ossification. Two patients had neurapraxia of lateral cutaneous nerve of forearm. Overall, surgical treatment of partial tear was recommended as a viable option achieving good to excellent outcome, if the non-surgical management fails.39

Eames and Bain44 described the arthroscopic technique for distal biceps pathology. Starting 2 cm distal to the anterior crease of the elbow, via a 2.5 cm longitudinal incision over the distal biceps tendon, the bursa is excised and an arthroscope is introduced into the bicipito-radial bursa to debride the distal biceps tendon. Nevertheless, this technique is for appropriately skilled surgeons.

The current literature for distal biceps tendinopathy or partial tear favours operative management after failed nonsurgical management. However, given that all publications, to-date, are based on case reports or small sized studies this conclusion is not based on robust evidence. Overall, non-operative treatment should be considered as the first line management in most cases, although patients must be informed about the potential complications (e.g., complete tear), and need for further surgery.

4. Distal triceps tendinopathy

4.1. Epidemiology, anatomy and pathophysiology

Distal triceps tendinopathy is the rare, and its incidence is unknown. Before the advent of MRI in a report of 1014 tendon injuries, triceps was affected in 8 cases (0.8%) of these, four cases were caused by lacerations.45 The most common age group was between 30 and 50 years with a slight male preponderance.45

The three heads of triceps form the footprint with medial head insertion area taking a mean of 100 mm2 and the conjoined tendon of long and lateral head inserting in an area of 308 mm2.46 The tendinopathy occurs on a broad spectrum of asymptomatic “degenerative tendinosis or partial tear” to “complete tear”. The term “partial tear” has been described to represent a wide spectrum of injury or degenerative changes along the tendon and is not well-defined. The pathophysiology is quite similar to other elbow tendinopathies, collectively known as angio-fibroblastic hyperplasia, which may rupture collagen fibril if tendon undergoes continued stress or is acutely injured. Tendon degeneration occurs secondary to intrinsic muscle-tendon overload which usually precedes a full thickness tear like in distal biceps tendinopathy.

Triceps rupture usually occurs through an area of abnormal tendon at the osseo-tendinous junction. So it is likely that tendinopathy occurs mostly at the insertion, however, other sites are also affected. It is often associated with use of anabolic steroids, weightlifting. Other risk factors include chronic renal failure,47 secondary hyperparathyroidism, local steroid injection and olecranon bursitis. All of these patients reported a pre-existing traumatic event either due to work or sport-related causes. Contracting triceps while eccentric loading in professional athletes has been implicated too.48

4.2. Diagnosis

Like other tendinopathies, activity-related pain is the main clinical feature.

On examination tenderness is usually present. Resisted extension aggravates the pain however, strength may be maintained. Haematoma and swelling may be present in Partial ruptures after an injury. The partial rupture affects the deeper portion of the tendon hence usually there is no gap felt but the strength may be diminished.49

Radiographs may show an avulsed fragment representing the triceps insertion (Fig. 5) proximal to the olecranon. US or MRI can be used to assess the amount of tendon changes, size of tear, amount of retraction and location, or any other changes (i.e., muscle oedema or atrophy). The superficial location allows for ultrasonography to easily evaluate the triceps tendon in elbow flexion. Ultrasound could show hypo-echogenicity and occasional calcification around the tendon insertion. MRI can assess other causes, as well as asses the deep layer of the tendon showing abnormal signal intensity and changes in surrounding soft tissues such as muscle atrophy/oedema (Fig. 6). In addition, US and MRI may help formulate the treatment strategy.

Fig. 5.

Plain radiograph of elbow demonstrates avulsed fragment. Of distal triceps insertion or ‘fleck’ sign (marked with arrow).

Fig. 6.

MRI of elbow illustrates degenerative changes within the distal portion of triceps tendon (marked with arrow).

4.3. Treatment

The management of distal triceps tendinopathy or partial tears remains controversial with sparse evidence available to date. The decision-making to consider non-operative or surgical management for partial tear secondary to tendinopathy is not well-described and relies on handful of case reports and a case-series.

Initial management of triceps tendinopathy is non-operative with rest, activity modification, NSAIDS, and physiotherapy. Symptomatic resolution can take a long time. Operative management is mostly for patients who fail non-surgical management or for patients who develop partial tears with concomitant loss of strength.

In a retrospective review by Mair et al., 10 out of 21 distal triceps ruptures were classified as partial tears. Of these, 6 healed without surgery with no residual weakness or pain48. The majority of their cohort were professional athletes with pain associated with some weakness after injury. Diagnosis was made after an examination and MRI. As per the MRI 8 were partial tears of the medial side (out of 10 partial tears). They suggested non-surgical management for defects of up to 75% on MRI. However, some patients opted for the surgery even with smaller defects.49

Bos et al.47 described successful outcomes in a young female with chronic renal failure, who was managed non-operatively using an elbow orthosis in 30° of flexion for duration of six weeks, for an acute avulsion partial tear involving the medial side, after a fall. At 6 months after injury she had full movements and strength.

In contrast, others advocate surgical treatment in partial tears. Van Riet et al.50 reviewed 23 distal triceps tendinopathy, of these 15 had partial tear of which 9 failed non-operative management and required further surgery (6 out of 9 required tendon graft). Although they recommended, surgery within 3 weeks after the injury for good results, all regained full recovery with no subsequent sequelae.

Athwal et al.49 in two patients described an endoscopic technique for distal triceps tendon repair with good outcomes. They repaired isolated, deep, medial head tears using 2 suture anchors.

5. Conclusion

An understanding of the natural history, the injury process, potential risk factors, and quantity of the pathologic spectrums are the Key considerations in the treatment of tendinopathies. Currently there are no disease-modifying treatments available for tendinopathy. Non-operative treatments, staged physiotherapy, and support are the best available first line options.

Most medial and lateral epicondylitis patients respond well to conservative management. Some may take 12 months to improve. The aetiology is degenerative and associated with repetitive overuse in the background of tendinopathy. Although NSAIDs and local corticosteroid injections may give short term symptomatic relief however, long term benefit is uncertain. Definitive evidence is lacking for other types of injections. Most tendinopathies are self-limiting. Surgery can be offered when non-operative management fails after 6–12 months of treatment. Most authors recommend open resection of diseased part and repair, although patients must be informed about the risk of infection with open techniques. Arthroscopic techniques have shown lower infection with similar functional recovery to open techniques, but risk of neurovascular injuries have been noted, in particular in patients with previous surgeries e.g. ulnar nerve transposition or other intra-articular procedures.

Distal triceps and biceps tendinopathies are rare, and the natural history is unknown. They usually have an acute traumatic aetiology. Timely diagnosis and prompt treatment improve results. Partial tears of less than 50% on MRI and without muscle atrophy can be treated nonoperatively using a sling or a brace. To ensure the tear does not progress a regular follow-up is a essential, usually progression to a complete tear is rare. However, If symptoms are troublesome even after 6 months of non-operative treatment or if the weakness persists, open repair using anchors or transosseus sutures could be performed. The outcomes are overall good to excellent in most cases with normal physiology.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors whose names are listed immediately below certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Smidt N., Van der Windt D.A. Tennis elbow in primary care. BMJ. 2006;333:927–928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39017.396389.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiri R., Viikari-Juntura E., Varonen H., Heliovaara M. Prevalence and determinants of lateral and medial epicondylitis: a population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:1065–1074. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leadbetter W.B. Cell-matrix response in tendon injury. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11:533–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraushaar B.S., Nirschl R.P. Tendinosis of the elbow (tennis elbow): clinical features and findings of histological, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopy studies. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1999;81-A 259–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cyriax J.H. The pathology and treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 1936;18:921–940. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner C.O. Lateral elbow pain and posterior interosseous nerve entrapment. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1979;174:1–62. doi: 10.3109/ort.1979.50.suppl-174.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saroja G., Leo A.P.A., Sai P.M.V. Diagnostic accuracy of provocative tests in lateral epicondylitis. Int J Physiother Res. 2014;2:815–823. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerezal L., Rodriguez-Sammartino M., Canga A. Elbow synovial fold syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:W88–W96. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savnik A., Jensen B., Nørregaard J. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of treatment response of lateral epicondylitis of the elbow. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:964–969. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki K., Tamakawa M., Onda K. The detection of the capsular tear at the undersurface of the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon in chronic tennis elbow: the value of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography arthrography. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long L., Briscoe S., Cooper C., Hyde C., Crathorne L. What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of conservative interventions for tendinopathy? An overview of systematic reviews of clinical effectiveness and systematic review of economic evaluations. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(8):1–134. doi: 10.3310/hta19080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smidt N., van der Windt D.A., Assendelft W.J., Devillé W.L., Korthals-de Bos I.B., Bouter L.M. Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;23;359(9307):657–662. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bisset L., Paungmali A., Vicenzino B., Beller E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials on physical interventions for lateral epicondylalgia. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:411–422. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.016170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hay E.M., Paterson S.M., Lewis M., Hosie G., Croft P. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of local corticosteroid injection and naproxen for treatment of lateral epicondylitis of elbow in primary care. BMJ. 1999;319:964–968. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7215.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coombes B.K., Bisset L., Brooks P., Khan A., Vicenzino B. Effect of corticosteroid injection, physiotherapy, or both on clinical outcomes in patients with unilateral lateral epicondylalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;309:461–469. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.129. (23) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gosens T., Peerbooms J.C., van Laar W., den Oudsten B.L. Ongoing positive effect of platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection in lateral epicondylitis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1200–1208. doi: 10.1177/0363546510397173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sims S.E.G., Miller K., Elfar J.C., Hammert W.C. Non-surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hand. 2014;9:419–446. doi: 10.1007/s11552-014-9642-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishra A., Collado H., Fredericson M. Platelet-rich plasma compared with corticosteroid injection for chronic lateral elbow tendinosis. PMR. 2009;1:366–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nirschl R.P., Pettrone F.A. Tennis elbow: the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1979;61-A:832–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calvert P.T., Allum R.L., Macpherson I.S., Bentley G. Simple lateral release in treatment of tennis elbow. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:912–915. doi: 10.1177/014107688507801106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhaar J., Walenkamp G., Kester A., van Mameren H., van der Linden T. Lateral extensor release for tennis elbow: a prospective long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1993;73-A:1034–1043. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrey B.F., An K.N. Functional anatomy of the ligaments of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;201:84–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baumgard S.H., Schwartz D.R. Percutaneous release of the epicondylar muscles for humeral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10:233–236. doi: 10.1177/036354658201000408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker C.L., Baker C.L. Long-term follow-up of arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:254–260. doi: 10.1177/0363546507311599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce T.P., Issa K., Gilbert B.T. A systematic review of tennis elbow surgery: open versus arthroscopic versus percutaneous release of the common extensor origin. Arthroscopy. 2017 Jun;33(6):1260–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shiri R., Viikari-Juntura E., Varonen H., Heliövaara M. Prevalence and determinants of lateral and medial epicondylitis: a population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:1065–1074. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vangsness C.T., Jr., Jobe F.W. Surgical treatment of medial epicondylitis. Results in 35 elbows. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991 May;73(3):409–411. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suresh S.P.S., Ali K.E., Jones H., Connell D.A. Medial epicondylitis: is ultrasound guided autologous blood injection an effective treatment? Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:935–939. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.029983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krischek O., Hopf C., Nafe B., Pompe J.D. Shock-wave therapy for tennis and golfer's elbow – 1 year follow up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999;119:62–66. doi: 10.1007/s004020050356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurvers H., Verhaar J. The results of operative treatment of medial epicondylitis. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1995;77:1374–1379. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199509000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabel G.T., Morrey B.F. Operative treatment of medical epicondylitis. Influence of concomitant ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1995;77:1065–1069. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Speach D.P., Lee D.J., Reed J.D., Palmer B.A., Abt P., Elfar J.C. Is medial elbow pain correlated with cubital tunnel syndrome? An electrodiagnostic study. Muscle Nerve. 2016;53:252–254. doi: 10.1002/mus.24719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.do Nascimento A.T., Claudio G.K. Arthroscopic surgical treatment of medial epicondylitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(12):2232–2235. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durr H.R., Stabler A., Pfahler M., Matzko M., Fefior J.J. Partial rupture of the distal biceps tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;374:195–200. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200005000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Safran M.R., Graham S.M. Distal biceps tendon ruptures: incidence, demographics and the effect of smoking. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:275–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chew M.L., Giuffre B.M. Disorders of the distal biceps brachii tendon. Radiographics. 2005;25:1227–1237. doi: 10.1148/rg.255045160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Athwal G.S., Steinmann S.P., Rispoli D.M. The distal biceps tendon: footprint and relevant clinical anatomy. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32:1225–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vardakas D.G., Musgrave D.S., Varitimidis S.E., Goebel F., Sotereanos D.G. Partial rupture of the distal biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:377–379. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.116518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frazier M.S., Boardman M.J., Westland M., Imbriglia J.E. Surgical treatment of partial distal biceps tendon ruptures. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:1111–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dellaero D.T., Mallon W.J. Surgical treatment of partial biceps tendon ruptures at the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:215–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luokkala T., Siddharthan S.K., Karjalainen T.V., Watts A.C. Distal biceps hook test - sensitivity in acute and chronic tears and ability to predict the need for graft reconstruction. Shoulder Elbow. 2020 Aug;12(4):294–298. doi: 10.1177/1758573219847146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shim S.S., Strauch R.J. A novel clinical test for partial tears of the distal biceps brachii tendon: the TILT sign. Clin Anat. 2018;31(2):301–303. doi: 10.1002/ca.23038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bourne M.H., Morrey B.F. Partial rupture of the distal biceps tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;271:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eames M.H., Bain G.I. Distal biceps tendon endoscopy and anterior elbow arthroscopy portal. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;7:139–142. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett J.B., Mehlhoff T.L. Triceps tendon repair. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:1677e83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madsen M., Marx R.G., Millett P.J., Rodeo S.A., Sperling J.W., Warren R.F. Surgical anatomy of the triceps brachii tendon: anatomical study and clinical correlation. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1839–1843. doi: 10.1177/0363546506288752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bos C.F., Nelissen R.G., Bloem J.L. Incomplete rupture of the tendon of triceps brachii. A case report. Int Orthop. 1994;18:273–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00180224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mair S.D., Isbell W.M., Gill T.J., Schlegel T.F., Hawkins R.J. Triceps tendon ruptures in professional football players. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:431–434. doi: 10.1177/0095399703258707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Athwal G.S., McGill R.J., Rispoli D.M. Isolated avulsion of the medial head of the triceps tendon: an anatomic study and arthroscopic repair in 2 cases. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:983–988. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Riet R.P., Morrey B.F., Ho E., O'Driscoll S.W. Surgical treatment of distal triceps ruptures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(10):1961–1967. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200310000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]