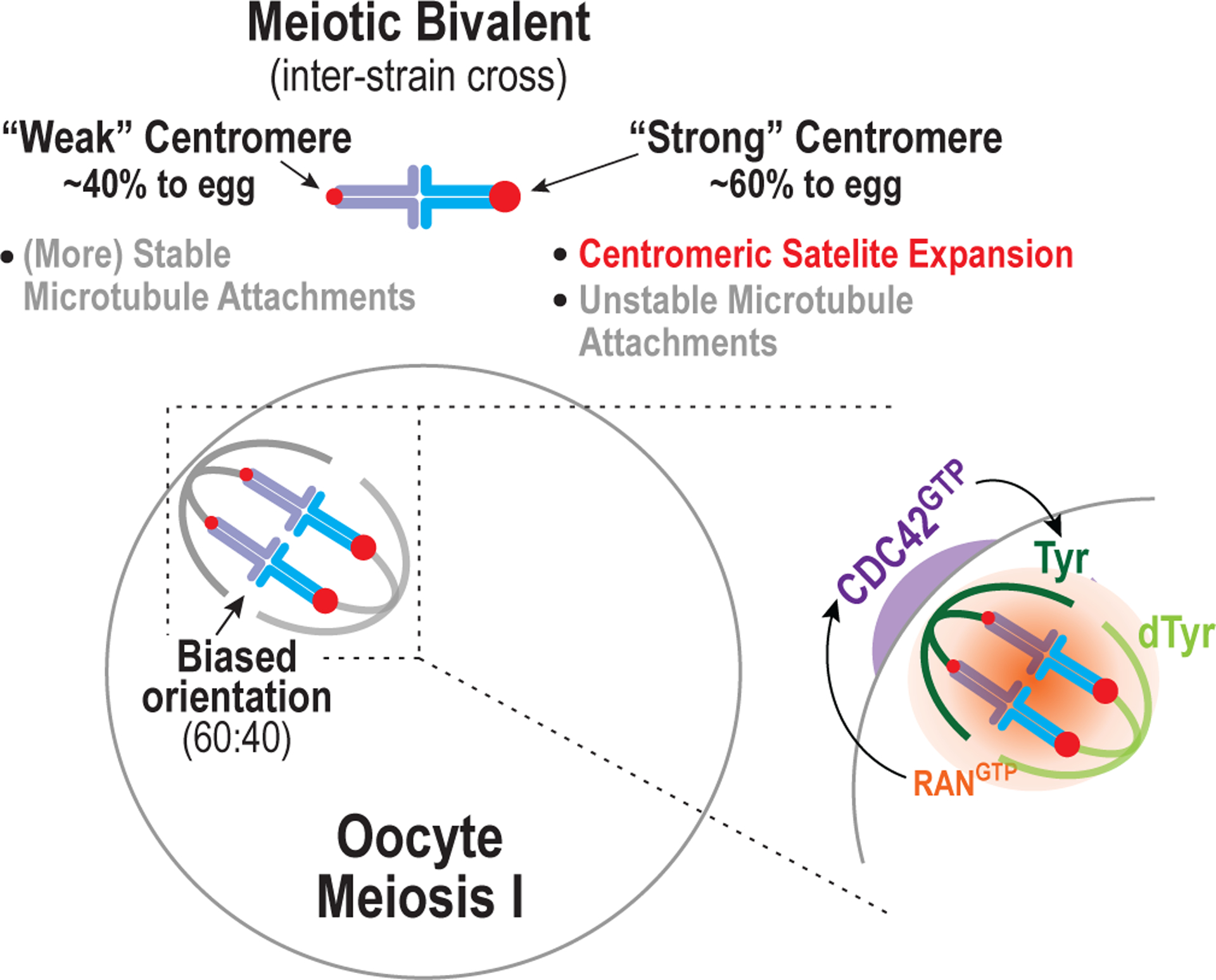

Figure 1. Mechanisms underlying asymmetric segregation in mammalian meiosis.

The figure depicts the biased orientation of bivalent chromosomes on the meiosis I spindle of oocytes after an inter-strain cross. One strain has ‘strong’ centromeres that have expanded centromeric minor satellite repeats and recruit more of a key microtubule attachment factor relative to the other strain with ‘weak’ centromeres. Surprisingly, strong centromeres make less stable microtubule attachments than weak centromeres. In oocytes of females derived from crossing the two strains, the chromosome with the strong centromere ends up in the egg more frequently than by chance (60% versus 50%). The spindle itself is asymmetric, in that its proximity to the cortex leads to elevated tyrosination of the microtubules of the half-spindle close to the cortex relative to the half-spindle facing the egg cytoplasm. The tyrosination asymmetry requires chromosome-derived Ran GTP that locally activates the Rho family GTPase Cdc42 on the oocyte cortex. The mechanism by which active Cdc42 promotes local tyrosination of microtubules is not yet known.