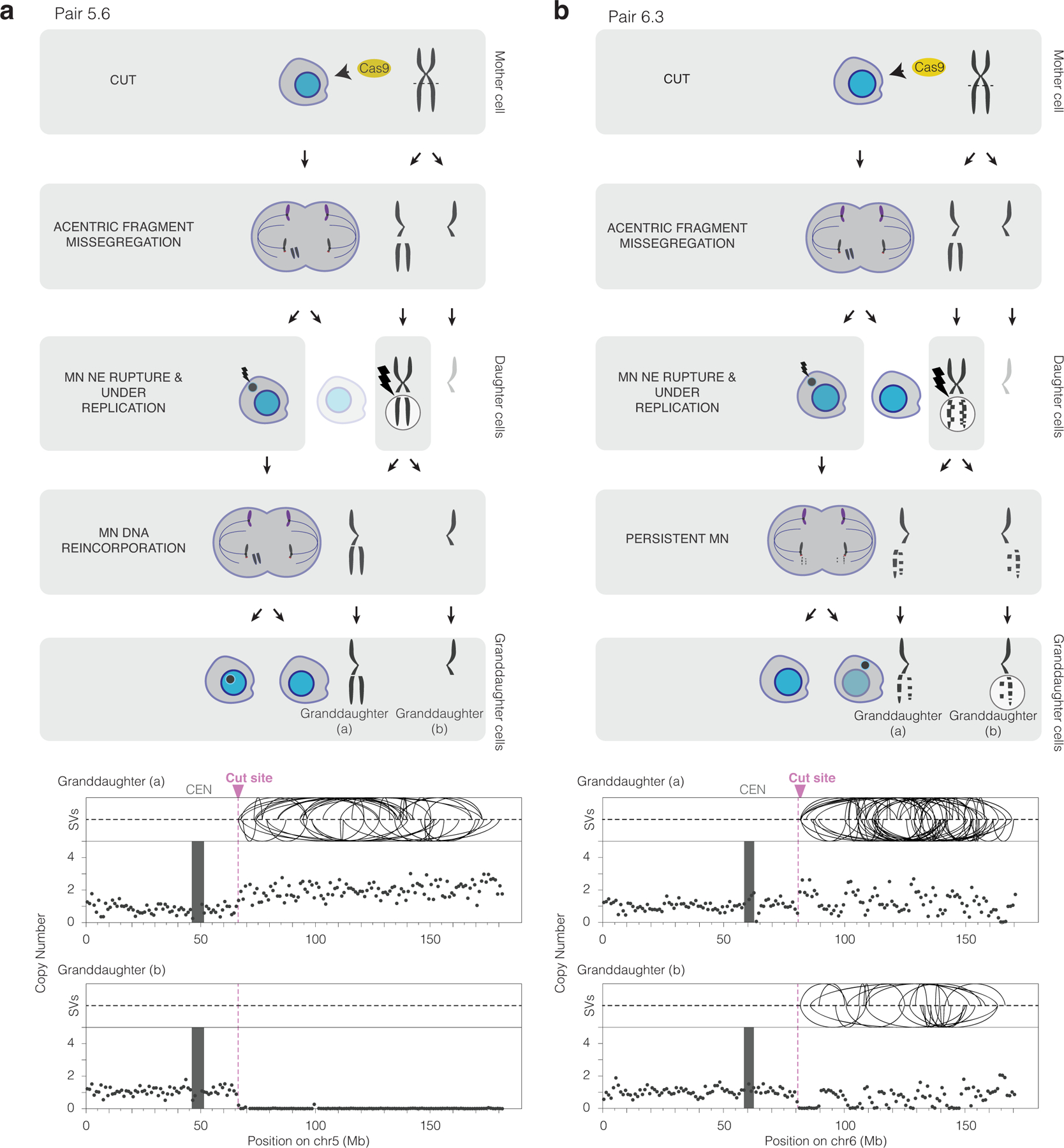

Figure 3. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing can cause chromothripsis.

(a) Chromothripsis after a micronucleus is reincorporated into a granddaughter cell. Left, cartoon depicting the cellular events leading to the genomic outcomes for CRISPR-Cas9 pair 5.6 (Extended Data Fig. 3). Cells are on the left and chromosomes are depicted on the right. In the first generation, both sisters from one homolog were cleaved in a G2 cell (horizontal dashed line) that divides to generate a micronucleated daughter (left) and a non-micronucleated daughter (right, faded cell not subsequently followed). DNA in the micronucleus is poorly replicated. In the second cell division, the micronuclear chromosome is reincorporated into a granddaughter cell’s primary nucleus. Lightning bolt: DNA damage. Right, plots showing structural variants (SVs) and DNA copy number for haplotype of the cleaved chromosome. Top, intrachromosomal SVs (> 1 Mb) are show by the curved lines. Bottom: copy number plot (1 Mb bins). CEN: centromere.

(b) Chromothripsis after the bulk of a micronuclear chromosome fails to be reincorporated into a granddaughter cell primary nucleus for pair 6.3 (Extended Data Fig. 3). Cartoon (left) and SV and copy number plots (right) as in (b). In this example, the two arms from cleaved sister chromatids are fragmented, generating chromothripsis in both daughters.