Figure 1.

Drosophila species native to a variety of thermal environments and with known differences in cold tolerance were chosen for behavioral analysis

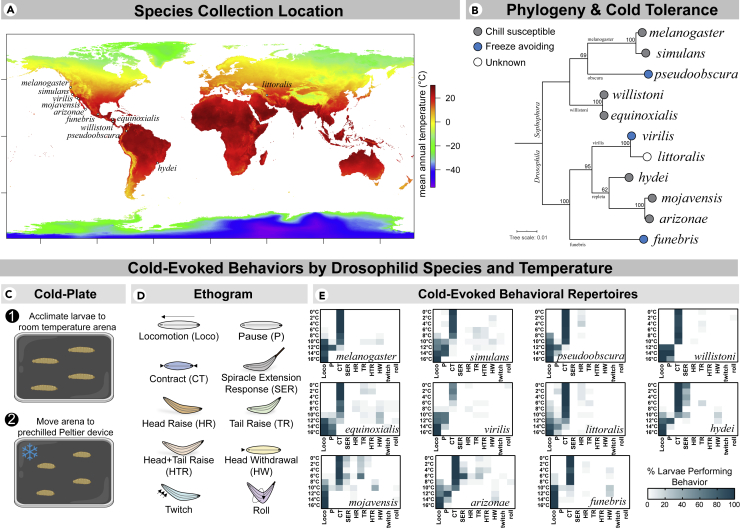

(A) Map of species stock collection location (provided by the Drosophila Species Stock Center) mapped on mean annual temperature, as extracted from climate data retrieved from WorldClim (https://www.worldclim.org) (Fick and Hijmans, 2017).

(B) Maximum likelihood phylogeny with ultrafast bootstrapping (at nodes). This tree was generated using concatenated and aligned CoI, CoII, and Adh sequences (Table S1). Most species chosen are chill susceptible (die in response to sub-freezing temperatures), while 3 are freeze avoiding (able to survive to the supercooling point) (Sinclair et al., 2015; Strachan et al., 2011).

(C) Outline of the previously developed cold-plate behavioral assay (Patel and Cox, 2017; Turner et al., 2016). Subject behaviors were recorded for 30s after application of cold.

(D) Ethogram representations of full cold-evoked behavioral repertories.

(E) Heatmap representations of full cold-evoked behavioral repertoires by species and temperature. The predominant cold-evoked response among drosophilid larvae is a bilateral, head-and-tail contraction (CT) behavior. Among repleta group species, an additional, highly stereotyped behavior termed the spiracle extension response (SER) is present at low temperatures. CT was typically transient; locomotion resumed at higher temperatures (at and above approx. 8°C, depending on species), and lasting, flaccid paralysis occurred at lower temperatures (approx. 0-10°C, depending on species). Larvae performed a variety of other behaviors at relatively low frequencies, with no obvious patterns. N = 2,970, n = 30 for each condition, each referring to the number of larvae assayed.