Abstract

Background/Aim: Cabazitaxel is recommended as first-line treatment after docetaxel for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. However, the efficacy, adverse events and prognostic factors associated with cabazitaxel are unclear. Patients and Methods: This single-centre retrospective study including 30 patients with CRPC treated with cabazitaxel between 2014 and 2020 investigated efficacy, outcomes and prognostic factors. Results: Fourteen patients had visceral metastases. The median cabazitaxel dose was 20 mg/m2. The prostate-specific antigen response rate, time to prostate-specific antigen response, and overall survival were 13.3%, 3.48 months, and 7.92 months, respectively. The rates of grade 3 or more neutropenia and febrile neutropenia were 20% and 6.7%, respectively. By multivariate analysis, sarcopenia and visceral metastasis at the time of cabazitaxel initiation were independent and significant factors conferring a poor prognosis. Conclusion: The early introduction of cabazitaxel, prior to the development of sarcopenia and visceral metastasis, might contribute to improved prognosis in CRPC.

Keywords: Sarcopenia, visceral metastasis, castration-resistant prostate cancer, cabazitaxel

Prostate cancer (PC), the most common cancer in males, is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths in developed countries (1,2). The development and widespread use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening tests have contributed to early detection and reduced mortality in patients with PC (3,4). However, approximately 10% of patients with PC are diagnosed with distant metastases (5). Androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) is the standard of care for patients with distant metastases of PC. It is also one of the main treatments after biochemical recurrence in patients with localised PC who have undergone local treatment such as surgery or radiation (6). Most patients with PC initially respond well to ADT. Nevertheless, failure of ADT is practically unavoidable, and disease in most patients eventually progresses to castration-resistant PC (CRPC) (7). Docetaxel was the only approved therapy shown to prolong survival in patients with CRPC (8) until the introduction of cabazitaxel, a novel taxane drug with activity against docetaxel-resistant CRPC (9). In the phase III TROPIC trial, cabazitaxel plus prednisone demonstrated significant antitumor activity and improved overall survival (OS) and disease progression during or after docetaxel-based therapy in patients with metastatic CRPC (9). However, in real-world clinical practice, there is limited information on the efficacy, adverse events, and prognostic factors associated with use of cabazitaxel (10-16). In the present study, we retrospectively evaluated the efficacy, adverse events and prognostic factors associated with cabazitaxel in patients with CRPC after chemotherapy.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective study included 30 patients with CRPC who were treated with cabazitaxel between November 2014 and August 2020 in Kanazawa University Hospital. All patients were histologically diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the prostate and initially treated with combined ADT, followed by chemotherapy. Chemotherapy included docetaxel in all patients except for one who received carboplatin plus etoposide. Cabazitaxel was administered as a 3-week regimen based on the TROPIC trial (9). The dose and schedule of cabazitaxel varied depending on the general condition and severity of adverse events in each patient. All patients maintained combined ADT and were treated with pegfilgrastim. Cabazitaxel treatment was continued until disease progression based on PSA measurement, imaging studies, adverse events or patient refusal of treatment. PSA failure after ADT was defined as a PSA level of at least 2.0 ng/ml higher than and 25% elevation from the nadir PSA level, which was confirmed by a second PSA test at least 4 weeks later. Patients fulfilling the abovementioned criteria were diagnosed with CRPC. The PSA response was defined as a PSA decline of 50% from the baseline value. In PSA non-responders, progression was defined as ≥25% increase from the nadir PSA level. In PSA responders and those not evaluable for PSA response at baseline, progression was defined as ≥50% increase from the nadir PSA level.

We retrospectively reviewed the charts of all patients and collected medical data, including age, serum PSA level, bone scan index (BSI), levels of C-reactive protein, alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, prostate biopsy pathology, adverse events, sarcopenia, clinical stage and treatment progress. BSI was calculated as the percentage of bone metastatic hotspots based on artificial neural network values using BONENAVI version 2 (FujiFilm RI Pharma, Tokyo, Japan; Exini Bone, Exini Diagnostics, Lund, Sweden) (17,18). Sarcopenia was defined as a skeletal muscle index (SMI) <43 cm2/m2 in patients with a body mass index (BMI) <25 cm2/m2 or an SMI <53 cm2/m2 in patients with a BMI ≥25 cm2/m2 (19). SMI and BMI were calculated as follows: BMI (kg/m2)=weight/height2; SMI (cm2/m2)=skeletal muscle cross-sectional area at L3/height2 (20,21). Clinical cancer stage was determined based on the eighth edition of the TNM classification published in 2017 (22). Diagnostic imaging studies such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and bone scintigraphy were performed at the time of PC diagnosis or CRPC occurrence and before changes in treatment. Thereafter, the imaging studies were left to the discretion of the attending physician. The interval between subsequent imaging studies and all therapeutic decisions were left to the discretion of the attending physician.

The follow-up was terminated on December 31, 2020. Survival was measured from the time of cabazitaxel administration until death or last follow-up. Time to PSA progression (TTP) and OS were retrospectively analysed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for the comparison of survival distributions. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using the commercially available SPSS software, version 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and Prism 5 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). In all analyses, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kanazawa University Hospital (2016-328).

Results

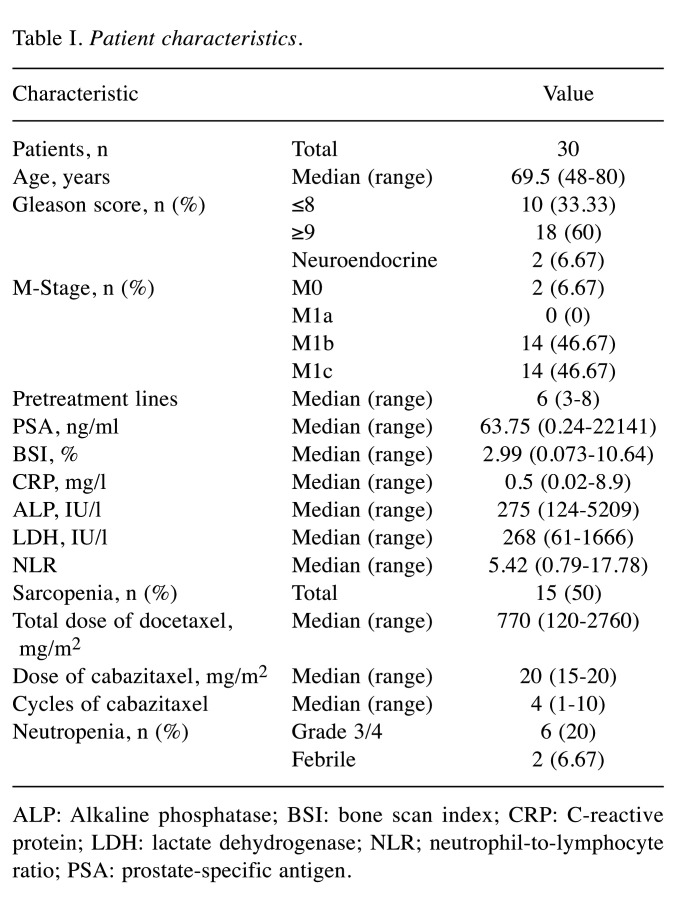

The characteristics of the study cohort of 30 patients with PC treated with cabazitaxel are shown in Table I. The median age at the time of cabazitaxel administration was 69.5 (range=48-80) years. The median PSA at the start of cabazitaxel treatment was 63.75 (range=0.24-22141) ng/ml. In the study cohort, 18 patients had a Gleason score ≥9, two patients had neuroendocrine PC, and 14 patients were in stage M1c indicating visceral metastasis (VM). A median of six (range=3-8) pretreatment lines and a median of four (range=1-10) cabazitaxel cycles were administered, with a median cabazitaxel dose of 20 (range=15-20) mg/m2. Grade 3 or higher neutropenia and febrile neutropenia (FN) were observed in six and two patients, respectively.

Table I. Patient characteristics.

ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; BSI: bone scan index; CRP: C-reactive protein; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; NLR; neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

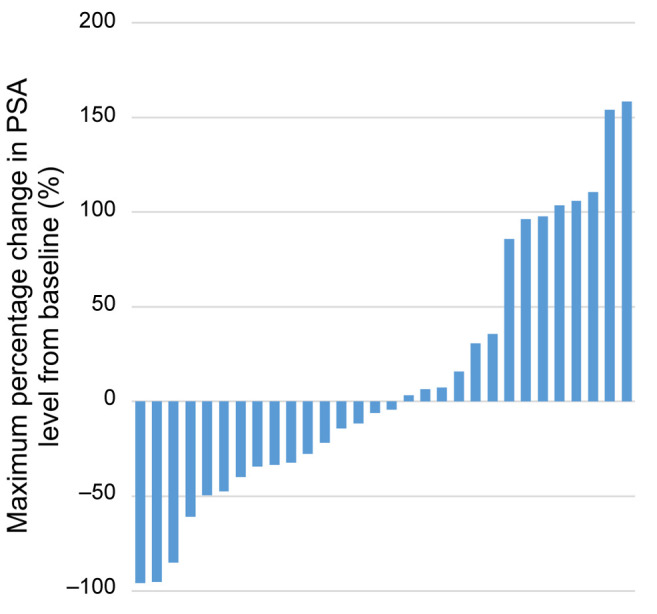

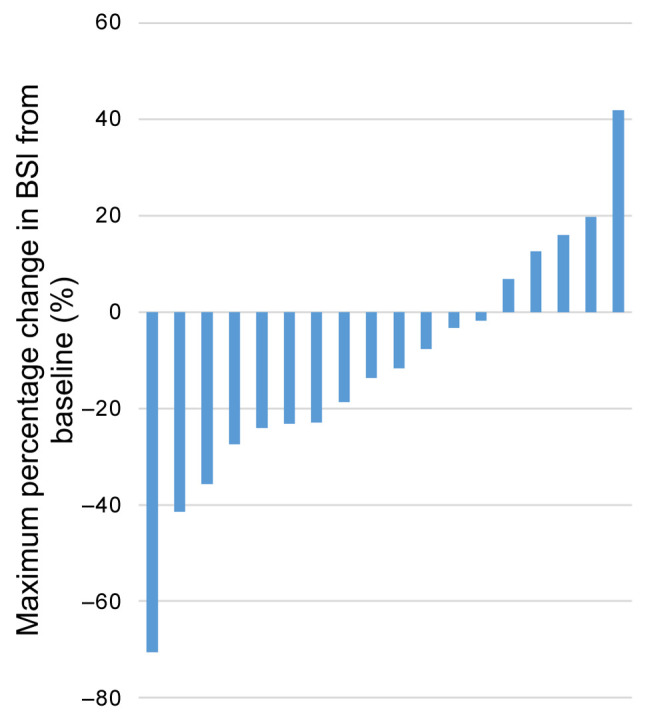

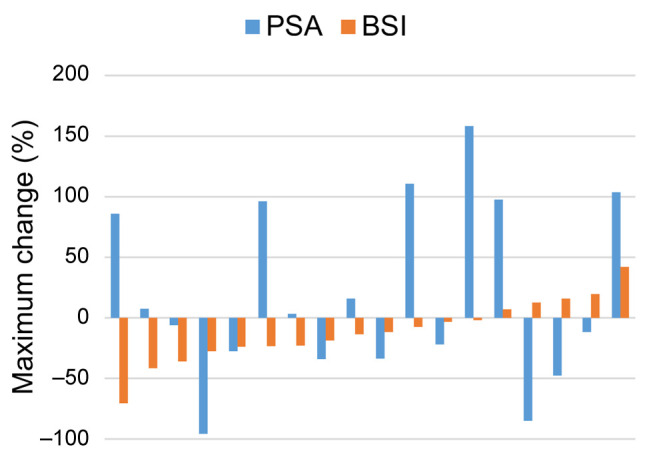

The waterfall plot of the maximum percentage change in PSA level from baseline after cabazitaxel administration is shown in Figure 1. Specifically, 16 out of the 30 patients (53.3%) exhibited a decrease in PSA and four patients (13.3%) exhibited PSA response. The waterfall plot of the maximum percentage change in BSI from baseline after cabazitaxel administration is shown in Figure 2. Briefly, 13 out of the 18 patients (72.2%) for whom BSI data were available exhibited a decrease in BSI. Finally, the waterfall plot showing the relationship between the maximum percentage change in PSA and the maximum percentage change in BSI (Figure 3) revealed that there was no correlation between the decrease in BSI and PSA.

Figure 1. Waterfall plot of the maximum percentage change in prostatespecific antigen (PSA) level from baseline after cabazitaxel administration.

Figure 2. Waterfall plot of the maximum percentage change in bone scan index (BSI) from baseline after cabazitaxel administration.

Figure 3. Waterfall plot showing the relationship between the maximum percentage change in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and bone scan index (BSI).

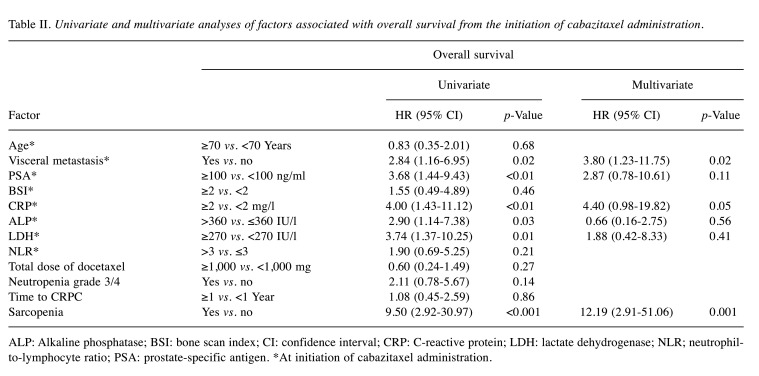

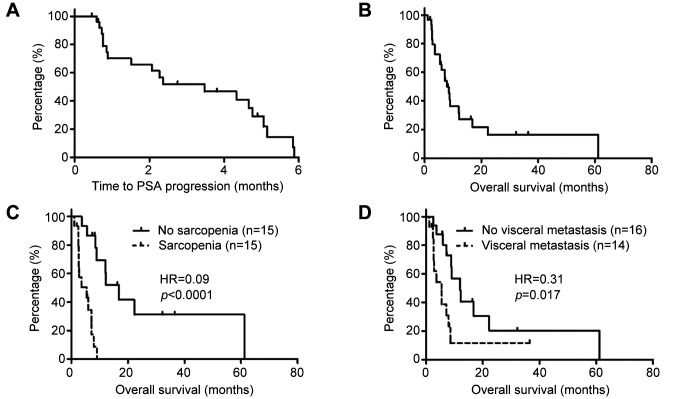

Table II shows the results of univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with OS from the time of cabazitaxel administration. Multivariate analysis showed that the presence of sarcopenia and VM at the time of cabazitaxel initiation were independent and significant factors indicating a poor prognosis. The median TTP and OS from the initiation of cabazitaxel administration were 3.48 months and 7.92 months, respectively (Figure 4A and B). As shown in Figure 4C, the median OS rates of patients with and without sarcopenia were 5.45 and 16.82 months, respectively (p<0.0001, log-rank test). As shown in Figure 4D, the median OS rates of patients with and without VM were 5.45 and 12.02 months, respectively (p=0.017, log-rank test). These results indicate that the OS was significantly shorter in patients with sarcopenia and in those with VM.

Table II. Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with overall survival from the initiation of cabazitaxel administration.

ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; BSI: bone scan index; CI: confidence interval; CRP: C-reactive protein; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; NLR; neutrophilto-lymphocyte ratio; PSA: prostate-specific antigen. *At initiation of cabazitaxel administration.

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier curves for time to prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression (A), and overall survival (OS) of the whole cohort (B) and of patients according to the presence of sarcopenia (C) and visceral metastasis (D). HR: Hazard ratio.

Discussion

Based on the results of the phase III TROPIC trial, 25 mg/m2 cabazitaxel in combination with prednisone was approved in 2010 for the treatment of patients with CRPC after docetaxel treatment (9). In the TROPIC trial, the median OS rates were 15.1 and 12.7 months for the cabazitaxel-treated and mitoxantrone-treated groups, respectively, showing a significantly longer OS for the cabazitaxel-treated group (p<0.0001) (9). The PSA response rate for the cabazitaxel group was 39.2%. Based on these results, the 2020 National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Prostate Cancer recommend cabazitaxel as first-line treatment for metastatic CRPC after docetaxel (23). In the TROPIC trial, 82% of patients had grade 3 or higher neutropenia and 8% of patients had FN (9). In a phase I trial from Japan, 100% of patients had grade 3 or higher neutropenia and 24.6% of patients had FN (24). Compared with patients from Western countries, disease in patients from Asian countries has generally been reported to exhibit stronger resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, and the cabazitaxel dosage for Japanese patients should be considered with caution (9,24,25). The phase III PROSELICA trial was conducted to investigate the safety and efficacy of low-dose cabazitaxel [20 mg/m2 (C20)] to 25 mg/m2 cabazitaxel (C25) (26). The PSA response rate was significantly higher for the C25 group compared to the C20 group (42.9% vs. 29.5%; p<0.001) but there was no significant difference in TTP (3.5 and 2.9 months, respectively; hazard ratio=1.099) and OS (14.5 and 13.4 months, respectively, hazard ratio=1.024) (26). The C20 group had a lower rate of grade 3 or higher neutropenia (42% vs. 73% in the C25 group) and FN (2.1% vs. 9.2% in the C25 group). Based on these results, treatment with 20 mg/m2 cabazitaxel is desirable due to improved prognosis with a lower rate of side-effects. For all patients in the present study, lower cabazitaxel doses of 15-20 mg/m2 were initiated.

In the present study, the rates of PSA response, grade 3 or higher neutropenia, and FN were 13.3%, 20%, and 6.7%, respectively, and the OS and TTP were 7.92 and 3.48 months, respectively. The reported rates of PSA response, grade 3 or higher neutropenia, and FN are 19-37%,18-100%, and 6.4-54.6%, respectively, with TTP and OS of 1.4-4.3 and 12.2-20.7 months, respectively (10-13,15,16,24). Therefore, compared with the previous reports, the patients in the present study experienced a lower PSA response rate, shorter OS and lower incidence of grade 3 or higher neutropenia and FN. The lower incidence of grade 3 or higher neutropenia and FN might be due to use of the reduced cabazitaxel dose. In this study, sarcopenia and VM at the time of cabazitaxel initiation were independent and significant factors conferring a poor prognosis. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status and VM have been reported to be factors of poor prognosis for OS after treatment with cabazitaxel, consistent with the current study results (27). It is known that cancer cachexia and sarcopenia develop as cancer progresses, and this was observed in about half of patients with advanced cancer (28). VM at the time of prostate cancer diagnosis is very rare but has been found to increase as treatment progresses (5). These results suggest that cabazitaxel should be introduced at an early stage of PC, without sarcopenia and VM. Several studies have reported that cabazitaxel is effective in patients with grade 3 or higher neutropenia, low neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and low BSI, but in this study, there were no significant differences in OS and TTP related to these factors (27,29-31).

There are several limitations to the current study. This was a retrospective study with a short observation period and included a small number of patients. Furthermore, PC treatment and the interval between imaging assessments were at the discretion of the attending physician. Therefore, the current study findings should be confirmed in large, long-term prospective studies.

Conclusion

In the present study, we found that sarcopenia and VM at the time of cabazitaxel initiation were independent and significant factors indicating a poor prognosis. Early introduction of cabazitaxel might contribute to improved prognosis in patients with CRPC.

Conflicts of Interest

All Authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Authors’ Contributions

H.I. designed the experiments. H.I., H.K., T.S., R.N., T.M., S.K., H.Y., S.K., K.I, and Y.K. collected clinical data. H.I., R.N., T.M., S.K., K.I. and A.M. analyzed the data. H.I., K.I., and A.M. drafted and revised the manuscript. All Authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byers T, Barrera E, Fontham ET, Newman LA, Runowicz CD, Sener SF, Thun MJ, Winborn S, Wender RC, American Cancer Society Incidence and Mortality Ends Committee A midpoint assessment of the American Cancer Society challenge goal to halve the U.S. cancer mortality rates between the years 1990 and 2015. Cancer. 2006;107(2):396–405. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Ciatto S, Nelen V, Kwiatkowski M, Lujan M, Lilja H, Zappa M, Denis LJ, Recker F, Páez A, Määttänen L, Bangma CH, Aus G, Carlsson S, Villers A, Rebillard X, van der Kwast T, Kujala PM, Blijenberg BG, Stenman UH, Huber A, Taari K, Hakama M, Moss SM, de Koning HJ, Auvinen A, ERSPC Investigators Prostate-cancer mortality at 11 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):981–990. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwamoto H, Izumi K, Shimada T, Kano H, Kadomoto S, Makino T, Naito R, Yaegashi H, Shigehara K, Kadono Y, Mizokami A. Androgen receptor signaling-targeted therapy and taxane chemotherapy induce visceral metastasis in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate. 2021;81(1):72–80. doi: 10.1002/pros.24082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharifi N, Gulley JL, Dahut WL. An update on androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(4):R305–R315. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris WP, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Androgen deprivation therapy: Progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6(2):76–85. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, Oudard S, Théodore C, James ND, Turesson I, Rosenthal MA, Eisenberger MA, TAX 327 Investigators Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1502–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, Hansen S, Machiels JP, Kocak I, Gravis G, Bodrogi I, Mackenzie MJ, Shen L, Roessner M, Gupta S, Sartor AO, TROPIC Investigators Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosaka T, Hongo H, Watanabe K, Mizuno R, Kikuchi E, Oya M. No significant impact of patient age and prior treatment profile with docetaxel on the efficacy of cabazitaxel in patient with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;82(6):1061–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00280-018-3698-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyake H, Matsushita Y, Watanabe H, Tamura K, Suzuki T, Motoyama D, Ito T, Sugiyama T, Otsuka A. Significance of de ritis (Aspartate Transaminase/Alanine Transaminase) ratio as a significant prognostic but not predictive biomarker in Japanese patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with cabazitaxel. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(7):4179–4185. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terada N, Kamoto T, Tsukino H, Mukai S, Akamatsu S, Inoue T, Ogawa O, Narita S, Habuchi T, Yamashita S, Mitsuzuka K, Arai Y, Kandori S, Kojima T, Nishiyama H, Kawamura Y, Shimizu Y, Terachi T, Sugi M, Kinoshita H, Matsuda T, Yamada Y, Yamamoto S, Hirama H, Sugimoto M, Kakehi Y, Sakurai T, Tsuchiya N. The efficacy and toxicity of cabazitaxel for treatment of docetaxel-resistant prostate cancer correlating with the initial doses in Japanese patients. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5342-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasuoka S, Yuasa T, Ogawa M, Komai Y, Numao N, Yamamoto S, Kondo Y, Yonese J. Risk factors for poor survival in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with cabazitaxel in Japan. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(10):5803–5809. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiota M, Nakamura M, Yokomizo A, Tomoda T, Sakamoto N, Seki N, Hasegawa S, Yunoki T, Harano M, Kuroiwa K, Eto M. Prognostic significance of lactate dehydrogenase in cabazitaxel chemotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer: A multi-institutional study. Anticancer Drugs. 2020;31(3):298–303. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takai M, Kato S, Nakano M, Fujimoto S, Iinuma K, Ishida T, Taniguchi M, Tamaki M, Uno M, Takahashi Y, Komeda H, Koie T. Efficacy of cabazitaxel and the influence of clinical factors on the overall survival of patients with castrationresistant prostate cancer: A local experience of a multicenter retrospective study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ajco.13441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto T, Ishizuka O, Oike H, Shiozaki M, Haba T, Oguchi T, Iijima K, Kato H. Safety and efficacy of cabazitaxel in Japanese patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Int. 2020;8(1):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadomoto S, Yaegashi H, Nakashima K, Iijima M, Kawaguchi S, Nohara T, Shigehara K, Izumi K, Kadono Y, Nakajima K, Mizokami A. Quantification of bone metastasis of Castration-resistant prostate cancer after enzalutamide and abiraterone acetate using bone scan index on bone scintigraphy. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(5):2553–2559. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakashima K, Makino T, Kadomoto S, Iwamoto H, Yaegashi H, Iijima M, Kawaguchi S, Nohara T, Shigehara K, Izumi K, Kadono Y, Matsuo S, Mizokami A. Initial experience with Radium-223 Chloride treatment at the Kanazawa university hospital. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(5):2607–2614. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, Reiman T, Clandinin MT, McCargar LJ, Murphy R, Ghosh S, Sawyer MB, Baracos VE. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: Skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(12):1539–1547. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amanuma M, Nagai H, Igarashi Y. Sorafenib might induce sarcopenia in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting carnitine absorption. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(7):4173–4182. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macaione I, Galvano A, Graceffa G, Lupo S, Latteri M, Russo A, Vieni S, Cipolla C. Impact of BMI on preoperative axillary ultrasound assessment in patients with early breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(12):7083–7088. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2017. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, Eighth Edition; p. pp. 191. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Network® NCC NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Prostate Cancer. Version 2, 2020. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf [Last accessed on February 24, 2021]

- 24.Nozawa M, Mukai H, Takahashi S, Uemura H, Kosaka T, Onozawa Y, Miyazaki J, Suzuki K, Okihara K, Arai Y, Kamba T, Kato M, Nakai Y, Furuse H, Kume H, Ide H, Kitamura H, Yokomizo A, Kimura T, Tomita Y, Ohno K, Kakehi Y. Japanese phase I study of cabazitaxel in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20(5):1026–1034. doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shigeta K, Kosaka T, Yazawa S, Yasumizu Y, Mizuno R, Nagata H, Shinoda K, Morita S, Miyajima A, Kikuchi E, Nakagawa K, Hasegawa S, Oya M. Predictive factors for severe and febrile neutropenia during docetaxel chemotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20(3):605–612. doi: 10.1007/s10147-014-0746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenberger M, Hardy-Bessard AC, Kim CS, Géczi L, Ford D, Mourey L, Carles J, Parente P, Font A, Kacso G, Chadjaa M, Zhang W, Bernard J, de Bono J. Phase III study comparing a reduced dose of cabazitaxel (20 mg/m2) and the currently approved dose (25 mg/m2) in postdocetaxel patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer-PROSELICA. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(28):3198–3206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otto T, Krege S, Suhr J, Rübben H. Impact of surgical resection of bladder cancer metastases refractory to systemic therapy on performance score: A phase II trial. Urology. 2001;57(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00867-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nipp RD, Fuchs G, El-Jawahri A, Mario J, Troschel FM, Greer JA, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Kambadakone A, Hong TS, Temel JS, Fintelmann FJ. Sarcopenia Is associated with quality of life and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Oncologist. 2018;23(1):97–104. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meisel A, von Felten S, Vogt DR, Liewen H, de Wit R, de Bono J, Sartor O, Stenner-Liewen F. Severe neutropenia during cabazitaxel treatment is associated with survival benefit in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): A post-hoc analysis of the TROPIC phase III trial. Eur J Cancer. 2016;56:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uemura K, Kawahara T, Yamashita D, Jikuya R, Abe K, Tatenuma T, Yokomizo Y, Izumi K, Teranishi JI, Makiyama K, Yumura Y, Kishida T, Udagawa K, Kobayashi K, Miyoshi Y, Yao M, Uemura H. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts prognosis in Castration-resistant prostate cancer patients who received cabazitaxel chemotherapy. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7538647. doi: 10.1155/2017/7538647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uemura K, Miyoshi Y, Kawahara T, Ryosuke J, Yamashita D, Yoneyama S, Yokomizo Y, Kobayashi K, Kishida T, Yao M, Uemura H. Prognostic value of an automated bone scan index for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with cabazitaxel. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):501. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]