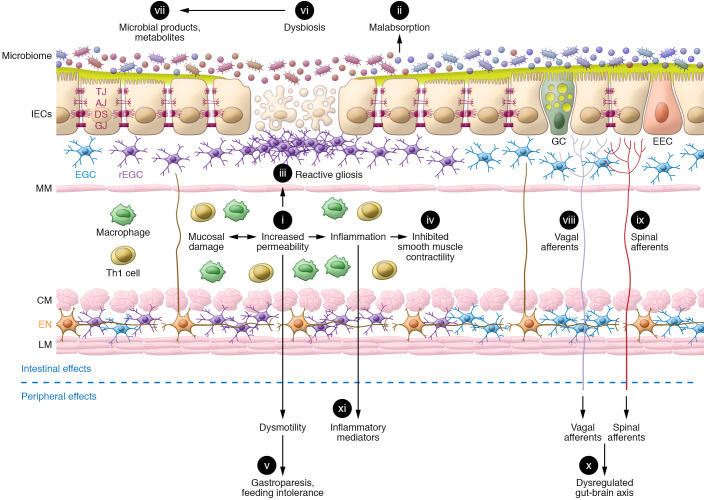

Figure 2. TBI induces significant changes in gut function.

The secondary sequelae of TBI in the gut include (i) mucosal damage associated with increased permeability and (ii) malabsorption of nutrients and electrolytes. Enhanced mucosal permeability mobilizes gut defenses, which include increased numbers of activated enteric glial cells culminating in (iii) reactive gliosis and generation of products that promote barrier function and epithelial repair. TBI-induced dysautonomia is characterized by sympathetic dominance, which in combination with the (iv) local release of proinflammatory mediators from resident and recruited immune cells inhibits smooth muscle contraction. These early TBI-induced effects on GI motility include (v) gastroparesis leading to food intolerance. Dysmotility also promotes (vi) changes in microbial composition and (vii) microbial products and metabolites. Compromised barrier function facilitates their passage across the mucosa, leading to activation of (vii) vagal and (ix) spinal afferents that are fundamental to (x) gut-brain communication. A secondary gut challenge such as enteric infection or inflammation prolongs the effects of i–xi and contributes to (xi) levels of circulating inflammatory mediators. Long-lasting systemic inflammation, dysautonomia, and dysbiosis contribute to the chronicity of TBI-induced effects on the gut as well as the increased susceptibility of TBI patients to GI disorders. IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; TJ, tight junctions; AJ, adherens junctions; DS, desmosomes; GJ, gap junctions; GC, goblet cells; EEC, enteroendocrine cells; EGC, enteric glial cells; rEGC, reactive EGC; MM, muscularis mucosae; Th1, T helper cells; CM, circular muscle; EN, enteric neurons; LM, longitudinal muscle.