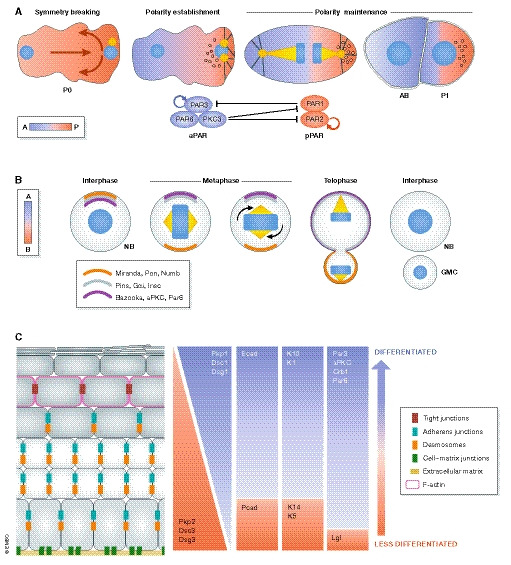

Figure 2. Coordination of cell polarity and cell fate determination: examples.

(A) The sperm entry site determines the anterior–posterior axis and gives rise to the first polarized cell of the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo (P0) (Nance & Zallen, 2011). Initially, PAR3, PAR6 and PKC3 (the aPKC homologue in C. elegans) are localized across the plasma membrane; however, a symmetry breaking event induces their anterior localization, hence referred to as the anterior polarity proteins (aPAR). PAR1 and PAR2 are evenly distributed within the cytoplasm and upon symmetry breaking are concentrated at the posterior pole, thus collectively referred to as the posterior polarity proteins (pPAR). The phosphorylation of pPAR proteins by PKC3 results in the establishment of the zygote a‐p polarity. aPARs are under constant inhibition by pPARs, i.e. PAR1 phosphorylates PAR3 and removes it from the cortex. The basis for this sorting process is the existence of actomyosin flow directed to the anterior part of the embryo, passively transporting the aPar proteins. After sorting, the actomyosin flow finally diminishes (in a Par‐dependent manner), which culminates in two domains with distinct Par polarity (polarity establishment) (Goehring et al, 2011; Gross et al, 2019). P0 cells eventually undergo an asymmetric cell division that produces a blastomere (AB) and a germline cell (P1). The two daughter cells will not only inherit different polarity proteins but also fate determinant molecules and structures like P‐granules, RNA multi‐phase condensates that become restricted to the posterior side and are segregated to the P1 germline cell (Goldstein & Macara, 2007; Hoege & Hyman, 2013; Rose & Gonczy, 2014; Illukkumbura et al, 2020). (B) The neuroblast (NB), the Drosophila melanogaster neural stem cell, sustains its self‐renewal capacity as a result of an asymmetric cell division (ACD). The two daughter cells display different fates and morphologies: a large pluripotent cell and a smaller one, committed to differentiation, called the ganglion mother cell (GMC). NBs are apico‐basally polarized and exhibit asymmetry of polarity proteins. Baz (Par3), aPKC and Par6 are enriched apically and restrict the localization of basal fate determinants. This is achieved by aPKC‐mediated phosphorylation of Numb and its scaffold protein Miranda, which displaces both proteins from the apical site to the basal cortex. Subsequently, the polarity and the spindle orientation machineries jointly mediate the segregation of apical and basal fate determinants. Inscuteable (Insc) binds Baz and Pins (LGN in mammals), which in turn connect Gαi to microtubules together with Mud (NuMA in mammals), a dynein‐binding protein. Together, they promote spindle reorientation along the apical–basal axis and segregation of fate determinants (Prehoda, 2009). (C) The murine epidermis displays apico‐basal polarization with differential expression of polarity proteins across the epidermal layers (Simpson et al, 2011; Niessen et al, 2012; Niessen et al, 2013; Ali et al, 2016). Likewise, cell adhesion and cytoskeletal components distribute asymmetrically within the epidermis. The basal layer expresses both P‐ and E‐cadherin, while in the suprabasal layers, E‐cadherin dominates. Similarly, desmosomal components distribute across the apico‐basal axis: the basal layer expresses desmocollin 2/3, desmoglein 3 and plakophilin 2, whereas desmocollin 1, desmoglein 1 and plakophilin 1 are largely confined to the suprabasal layers. Tight junctions are restricted to the last viable layer, the stratum granulosum (SG2) and participate in the epidermal barrier. Likewise, the epidermal cytoskeleton exhibits apico‐basal polarization. Intermediate filaments vary in their set‐up across the epidermis, with specific expression of keratin K5/K14 heterodimers in the basal layer and K1/K10 dimers in suprabasal layers. Actin is enriched in the SG2 layer, associated with the formation of a junctional actomyosin ring (Simpson et al, 2011; Baroni et al, 2012). Intracellular organelles such as the centrosome, Golgi apparatus and cilia are also apico‐basally polarized in the skin epidermis (Muroyama & Lechler, 2012). The skin also manifests planar cell polarization of hair follicles across the anterior–posterior and proximal–distal axis (Devenport, 2014).