Abstract

The Handover process is an essential aspect of patient care in daily clinical practice to ensure continuity of patient care. Standardization of clinical handover may reduce sentinel events due to inaccurate and ineffective communication. Single arm experimental trial was conducted to assess the effect of standard Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) protocol implementation in overall bedside nursing handover process, patient satisfaction, and nurses’ acceptance. As a sample, all nursing staff of specified unit, all handover process performed by them, and patients admitted during study the period were included. Initially, the prevailing handover process and patient satisfaction regarding nursing handover was assessed using a structured observation checklist. During the implementation phase, nurses were trained on an SBAR handover protocol. After implementation, nursing handovers were again assessed and data regarding patient satisfaction and nurses’ acceptance were collected. There was a statistically significant difference (P < .05) in median scores between the pre and post-intervention group on overall nursing handover and patient satisfaction regarding nursing handover. Standardization of patient’s handover process is effective in terms of improving nursing handover process, patient satisfaction, and health professionals’ acceptance.

Keywords: patient satisfaction, clinical hand over, quality care, nursing care, handover protocol

Introduction

Hospitals are the place where various methods of communication take place. Multiple numbers of healthcare professionals take care of the patients during any patient’s treatment period in health care settings. Each caregiver working with a patient must provide accurate and updated information to other caregivers (1). Clinical handover is an important component to maintain continuity of patient care further patient engagement and communication at transitions of care improve patient care outcomes, prevent adverse events during care, and reduce readmissions to hospital after discharge. To ensure patient safety after handing over, right information should be transferred and accepted by the right people at the right time. Nursing handovers take place thrice or more times in a day according to the shift timings and as necessary. Nurses are legally responsible and accountable for transferring important patient-specific information during handovers (2,3).

The handover process plays an important role in nurses’ day-to-day clinical practice. During nursing handovers, responsibility and accountability for the care of a patient are transferred from one nurse to another. Numerous patient-specific information is transferred during this time. Transfer and acceptance of responsibility for patient care are attained through successful communication (3).

This is also the high time where communication may be inaccurate and the handover process may become ineffective. The Joint Commission identified communication failure as the major cause of patient suffering (4). To organize information in clear and concise format which will help in facilitating effective communication among health care providers; the Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) model was developed. A systematic review of nursing handover has reported SBAR as the most frequently used handoff tool (5,6). Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation refers to a patient handover system in which Situation refers to patient’s name, age, sex, bed number, and chief complaint for admission. Background refers to the patient’s admitting diagnosis and number of hospital stays since admission and past history. Assessment refers to patient’s recent vital signs and other diagnostic reports and present clinical condition. Recommendation refers to patient’s management of the condition (7).

Structured clinical handover has been shown to reduce communication errors within and between health service organizations and to improve patient safety and care because critical information is more likely to be accurately transferred and acted on (1,2). This is especially important at transitions of care, when communication errors are more likely and there is an increased risk of information being miscommunicated or lost. Ineffective communication at clinical handover is also associated with clinicians spending extensive time attempting to retrieve relevant and correct information (3). This can result in inappropriate care and the possibility of misuse or poor use of resources.

It can be hazardous to both patients and staff if the handover is ineffective, such as incomplete information or wrong information provided (6 –8). Different hospitals, units, and nurses follow different methods of delivering shift reports. Irrelevant, narrative, and repetitive information often hampers the communication process. Moreover, nursing handoffs take place at busy times of the day with multiple distractions and time constraints which makes shift reports more likely to have errors (9,10). Therefore, communication methods should be standardized by incorporating the SBAR framework in it. This standardization can help in sequencing information exchanges and promoting patient safety during handover.

Involving the patient in the nursing handover process by allowing them to ask their queries and provide information regarding plan of care can improve patient satisfaction. Involving patients in nursing handover also makes them aware of their respective nurses in each shift which helps in building good nurse–patient relationship (8,10). Chances of fragmentation of patient care and miscommunication related to adverse incidents are reduced when patients are involved in handovers and leads to greater continuity of care.

Method

Study Design

A single-arm experimental trial was done to assess the effect of standardized nursing handover protocol implementation on overall bedside nursing handover, patient satisfaction, and nurses’ acceptance. The secondary outcome was to assess the compliance of the nurses toward the implemented protocol at the end of the second and third months. Permission for the study was obtained from the Institute ethical committee, Human studies, Reg. No: JIP/IEC/2018/018. Trial registration was done under the Clinical Trials Registry—India (ICMR-NIMS), Reg. No: CTRI/2018/09/015835.

Sample Size and Selection Criteria

Complete enumeration was used for participation in the study. All staff nurses working in the surgical gastroenterology ward and patients admitted in the same ward during the study period (5 months) were included in the study. A total of 2696 nursing handover processes, 52 patients, and 10 nurses were enrolled in the study using an observation checklist and a structured questionnaire. Among the total 2696 observed nursing handover processes, 1226 were observed during the preintervention period, 1226 were observed during the postintervention period, 122 were observed during the second month audit, and 122 were observed during the third month audit. Among 52 patients, 26 patients were included during the preintervention period and 26 were included during the postintervention period.

Procedure

As represented in Figure 1, during the preimplementation phase, handing over strategy was assessed with the help of a structured observation checklist, and data regarding patient satisfaction regarding their involvement in the plan of care with the nursing handover process was assessed by the investigators which included 2 members team. This checklist included 4 items on Communication of plan of care to patients, patients satisfaction on information provided about a plan of care, whether the outgoing nurse introduced the oncoming nurse during the change of shift to the patients, Presence of open communication between health care providers regarding patient’s plan of care.

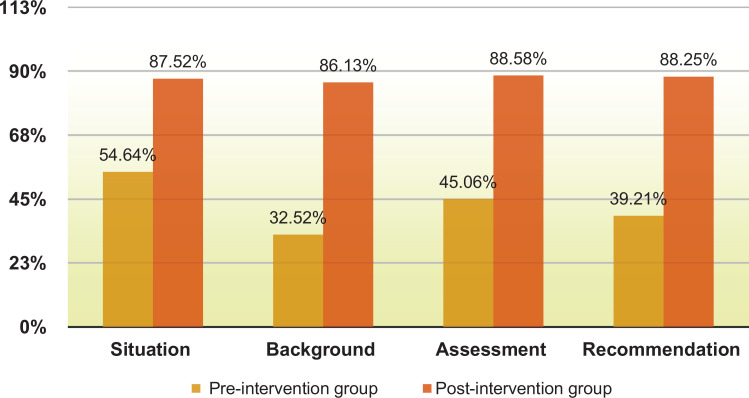

Figure 1.

Comparison of SBAR components compliance after implementation of Standardized handover protocol. SBAR indicates Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation.

Then the nurses were trained on SBAR handover protocol (which includes situation, background, assessment, and recommendation) with the help of lecture cum discussion and Self-instructional module followed by demonstration on handover using SBAR protocol by the investigators. After implementation of standardized nursing handover protocol, again handover practice and patient satisfaction regarding the information provided to them during handover time and their participation in plan of care were assessed. Nurses’ acceptance toward the implemented protocol was assessed during postintervention period. Compliance to the implemented standardized protocol was checked at 2-month and 3-month interval. The major part of data was collected by participant observation method, as investigator was posted in that specific area for clinical experience.

Data Collection Instruments and Scoring

The data of demographic profile and handover timing consisted of 4 variables namely shift time, days, educational qualification, and experience in years. Based on educational qualification, the study participants were categorized as BSc Nursing, MSc nursing, and GNM. Experiences were categorized as from 0 to5 years’ experience, 5 to 10 years’ experience, and more than 10 years’ experience. Components of a standardized nursing handover protocol section include the 5 categories (time, place, process, interaction, and patient communication) against which the nursing handover practice was assessed. A single part questionnaire was developed to collect data regarding patient satisfaction on nursing handover and to collect data regarding nurses’ acceptance of the introduction of standardized nursing handover protocol which consisted of 7 questions.

Two marks were given for the presence of SBAR components and 0 marks for absence. For other components, 1 mark was given for the presence of action and 0 for absence. Thus, total marks were 14 for the overall nursing handover score. To interpret, the score was distributed as >11 (>80%) as satisfactory and <11 (<80%) as unsatisfactory. Regarding patient satisfaction, the answer related to high satisfaction is given a score of 3 and the least satisfaction gets a score of 1. Thus, a total of 12 marks were allotted under patient satisfaction. Content validity index (0.74) was established to check the relevance of the items in the tool. The reliability of the tool established by the test retest method was found to be 0.8.

Results

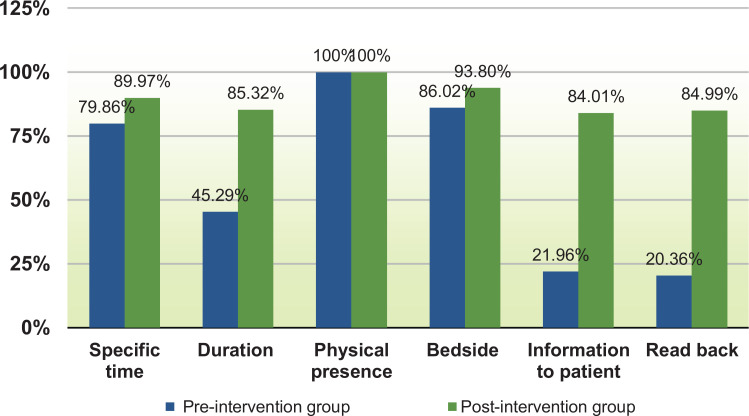

Regarding duty shift timing, there was an almost equal percentage of observation in each shift in both pre- and postintervention groups were observed. Regarding the day of observation, a maximum number of observations are done on the weekdays (64.21% and 69.33%) in both pre- and postinterventional groups. In both groups, the majority of the handover was given by the graduate nurses (72.49% and 74.71%). According to years of experience, the groups were almost equally divided into 2 categories that is, 0 to 5 years and 6 to 12 years. Physical presence that is, face-to-face handover was present always (100%) in both the pre- and postintervention group. Compliance of SBAR and all other components of the standard nursing handover process were more appreciated in the postintervention group as represented in Figures 1 and 2. There was a significant difference (P < .05) in the median scores between the preintervention and postintervention on overall nursing handover. Hence, the nursing handover was significantly improved after the implementation of a standardized protocol. Also, there was a significant difference (P < .05) in the median scores between the preintervention and postintervention on patient satisfaction regarding nursing handover. Hence, patient satisfaction regarding nursing handover significantly improved after the implementation of a standardized protocol (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Comparison of other components standard nursing handover compliance among pre- and postintervention group.

Table 1.

Comparison of Nursing Handover and Patient Satisfaction Score in the Pre- and Postinterventional Group.a

| Area of assessment | Preintervention (n = 1226) | Postintervention (n = 1226) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Interquartile range | Median | Interquartile range | ||

| Overall clinical handover score | 7 | (5–9) | 13 | (11–14) | .000# |

| Patient satisfaction score | 11 | (10–12) | 12 | (11–12) | .024* |

a N = 2452

b Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

c Mann-Whitney U test; P < .05.

The secondary outcome was to assess the compliance of the nurses toward the implemented protocol at the end of the second month and third months. The result reveals that there was no significant difference (P > .05) in the median scores among immediate postintervention and during second audit (at the end of second month) and third audit (at the end of third month) on overall nursing handover, which indicates there was good compliance to the implemented standardized protocol at immediate postintervention period and at 2 months and 3 months intervals also.

The correlation between the SBAR score and the overall handover score in the pre- and postintervention period and audit points was done. At each point, the result indicates a good positive correlation between the SBAR score and the overall nursing handover score which indicates the improvement of the overall handover score was due to better utilization of SBAR protocol. The results are statistically significant (P < .05). Table 2 shows the association between overall nursing handover score with nurse’s demographic variables and handover timing. The findings show that the educational qualification of nurses (0.001), shift time (0.000), and days (0.009) are associated with the total handover score. The experience of the nurses is not associated with the total handover score. The handover score was satisfactory among the MSc nurses, morning shift and during holidays, which was significant at P < .05.

Table 2.

Association Between Overall Clinical Handover Score With Nurse’s Demographic Variables and Handover Timing.a

| Parameters | Total handover score | P valueb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfactory handover score | Unsatisfactory handover score | |||||

| Educational qualification of nurses | BSc Nursing | 687 | 75% | 229 | 25% | .001c |

| Msc Nursing | 135 | 81.82% | 30 | 18.18% | ||

| General Nursing Midwifery | 91 | 62.76% | 54 | 37.24% | ||

| Shift time | Morning | 341 | 83.78% | 66 | 16.22% | .000c |

| Evening | 299 | 73.46% | 108 | 26.54% | ||

| Night | 273 | 66.26% | 139 | 33.74% | ||

| Days | Weekday | 649 | 76.35% | 201 | 23.65% | .009c |

| Weekend | 213 | 68.05% | 100 | 31.95% | ||

| Holiday | 51 | 80.95% | 12 | 19.05% | ||

| Experience | 0-5 years | 467 | 74.72% | 158 | 25.28% | 0.445 |

| 6-12 years | 446 | 74.21% | 155 | 25.79% | ||

a N = 1226.

b Fisher exact test; P < .05.

c P < 0.001.

Discussion

In the present study, standardized SBAR nursing handover protocol implementation had a positive effect on bedside nursing handover. The overall nursing handover score after implementation of SBAR protocol was higher in the postintervention group compared to the preintervention group. The overall nursing handover score included 5 categories (time, place, process, interaction, and patient communication) against which the nursing handover practice was assessed. In all 5 categories, there was an improvement in the postintervention group. Similar findings were reported in a study conducted by Crompton et al, the result of the study demonstrates improvement in hospital communication using SBAR format (11-12). A systemic review conducted by Muller et al shows average evidence for improvement of patient safety through SBAR communication protocol, mainly when used in telephonic conversation (13).

In the present study, patient satisfaction was assessed during the pre- and postintervention period using a structured questionnaire containing 4 questions. The patient satisfaction score regarding nurses’ handover process significantly increased in the postintervention group compared to the preintervention group. Whereas, the results of other studies indicate positive but not significant difference after implementing standardized SBAR protocol in nursing handover. The findings of the study conducted by Townsend et al conclude as patient satisfaction was trended toward a positive result, but was not significant (14).

The SBAR has an encouraging impact on improving communication between nurses and increasing their job satisfaction. Thus, the application of such a standardized instrument retains and reassures good communication relationships (15 –17). In this study, nurses’ acceptance was analyzed during the postintervention period using a structured questionnaire that contains 7 questions related to acceptance. The items included in all 7 questions, nurses gave positive responses to the implemented standardized nursing handover process. The result of the study conducted by Abela et al showed that the structure of handover procedures and the use of the SBAR tool can improve the impact of handover and staff satisfaction. Satisfaction regarding the information received during handover increased from 34% to 41% (19). In the result of the study conducted by Fabila et al, recipients’ perception about the new handover protocol indicated improvement in information adequacy and clearness, decrease errors, and lesser inconsistencies in the patient described in the new procedure (18,19).

In the present study, compliance to the implemented nursing handover protocol was assessed by conducting auditing for 2 days (1 weekday, 1 weekend) at the interval of 2 months and 3 months of the protocol implementation. The results of the audits show there was no significant difference (P > .05) in overall nursing handover score at the interval of 2 and 3 months when compared with the immediate postintervention overall nursing handover score. That indicates there was good compliance to the implemented standard nursing handover protocol at 2- and 3-month intervals also. In a study conducted by Achrekar et al, compliance to SBAR documentation was done by auditing retrospectively at first week and 16th week, after the introduction of the self-instructional module. There was a statistically significant difference invalid percent score of 4% between the 2 audit points. A significant improvement (P = .043) in overall scores between audit points was seen. This difference was thought to be due to the regular practice of the implemented form (20).

There are some limitations to this study. Since the study was conducted only in one ward, the findings may not be generalizable. Though the participant observation method was followed, there is the possibility of the Hawthorne effect which can affect the study result.

Conclusion

The current study supports the need for standardization of the nursing handover process by incorporating SBAR protocol in it. The standardization was effective in improving the nursing handover practice. So, it is concluded that the implementation of a standardized nursing handover process is effective in terms of patient satisfaction and nurses’ acceptance. This study can be used as a future reference since it emphasizes quality improvement of the handover process by standardizing it.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Dr Tanveer Rehman, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, JIPMER, for statistical analysis and presentation of data of the study.

Author Biographies

Sayani Ghosh was an MSc Medical-surgical Candidate at JIPMER, Puducherry. Currently, working as a tutor in a Nursing Institute at Kolkatta, India.

Lakshmi Ramamoorthy is Working as an assistant professor in the Medical-Surgical Nursing discipline at the College of Nursing, JIPMER, India. She has More than 12 years of teaching experience and training Undergraduate and Post Graduate students in Nursing.

Biju Pottakkat is working as a professor in Surgical Gastro Enterology, JIPMER, India. He has extensive experience in patient care and training of post Graduates in Surgical Gastro Enterology Skills for more than 15 years.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The study was approved by Institute ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from every participant and nurses after a brief explanation regarding the study by the investigator.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Lakshmi Ramamoorthy, MSc, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4248-1407

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4248-1407

References

- 1. Usher R, Cronin SN, York NL. Evaluating the influence of a standardized bedside handoff process in a medical-surgical unit. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2018;49:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Joint Commission. National patient safety goals. Hand-off Communications: standardized approach; 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2019, from: http://www.jointcomission.org/AccreditationAmbulatoryCare/.

- 3. Slade D, Pun J, Murray KA, Eggins S. Benefits of health care communication training for nurses conducting bedside handovers: an Australian hospital case study. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2018;49:329–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Communication During Patient Hand-Overs - World Health Organization, May 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from: https://www.who.int/patientsafety/solutions/patientsafety/PS-Solution3.pdf.

- 5. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2011. Implementation Toolkit for Clinical Handover improvement. Retrieved August 15, 2020, from: www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/resources/acutecare/safe_clinical_handover/implementation-toolkit.

- 6. Uhm JY, Lim EY, Hyeong J. The impact of a standardized inter-department handover on nurses’ perceptions and performance in Republic of Korea. J Nurs Manag. 2018;26:933–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clarke CM, Persaud DD. Leading clinical handover improvement: a change strategy to implement best practices in the acute care setting. J Patient Saf. 2011;7:11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kumar P, Jithesh V, Vij A, Gupta SK. Need for a hands-on approach to hand-offs: a study of nursing handovers in an Indian neurosciences center. Asian J Neurosurg. 2016;11:54–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ernst KM, McComb SA, Ley C. Nurse-to-nurse shift handoffs on medical-surgical units: a process within the flow of nursing care. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:1189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Funk E, Taicher B, Thompson J, Iannello K, Morgan B, Hawks S. Structured Handover in the Pediatric Postanesthesia Care Unit. J Perianesth Nurs. 2016;31:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Street M, Eustace P, Livingston PM, Craike MJ, Kent B, Patterson D. Communication at the bedside to enhance patient care: a survey of nurses’ experience and perspective of handover. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17:133–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Compton J, Copeland K, Flanders S, Cassity C, Spetman M, Xiao Y, et al. Implementing SBAR across a large multihospital health system. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38:261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Müller M, Jürgens J, Redaèlli M, Klingberg K, Hautz WE, Stock S. Impact of the communication and patient hand-off tool SBAR on patient safety: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Townsend-Gervis M, Cornell P, Vardaman JM. Interdisciplinary rounds and structured communication reduce re-admissions and improve some patient outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2014;36:917–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abela-Dimech F, Vuksic O. Improving the practice of handover for psychiatric inpatient nursing staff. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32:729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bonds RL. SBAR tool implementation to advance communication, teamwork, and the perception of patient safety culture. Creat Nurs. 2018;24:116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGrath JK, Elertson KM, Morin T. Increasing patient safety in hemodialysis units by improving handoff communication. Nephrol Nurs J. 2020;47:439–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fabila TS, Hee HI, Sultana R, Assam PN, Kiew A, Chan YH. Improving postoperative handover from anaesthetists to non-anaesthetists in a children’s intensive care unit: the receiver’s perception. Singapore Med J. 2016;57:242–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dalky HF, Al-Jaradeen RS, AbuAlRrub RF. Evaluation of the situation, background, assessment, and recommendation handover tool in improving communication and satisfaction among Jordanian nurses working in intensive care units. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2020;39:339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Achrekar MS, Murthy V, Kanan S, Shetty R, Nair M, Khattry N. Introduction of situation, background, assessment, recommendation into nursing practice: a prospective study. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2016;3:45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]