Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exos) are phospholipid bimolecular vesicles containing various materials, and they mediate crosstalk among cells. MSC-exos can maintain glucose homeostasis and delay the progression of diabetes and its microvascular complications through multiple mechanisms, such as by improving β-cell viability and insulin resistance as well as through multiple signal transduction pathways. However, related knowledge has not yet been systematically summarized. Therefore, we reviewed the applications and relevant mechanisms of MSC-exos in treatments for diabetes and its microvascular complications, particularly treatments for improving islet β-cells viability, insulin resistance, diabetic nephropathy, and retinopathy.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cell, diabetes, exosomes, microvascular complications

Introduction

Exosomes secreted by mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are phospholipid bimolecular vesicles containing proteins, lipids, and various nucleotides [1]. MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-exos) have attracted attention because they mediate various physiological and pathological processes, including nerve regeneration, atherosclerosis, fibrosis, and immune regulation [2-5]. Diabetes is a clinical syndrome characterized by chronic hyperglycemia. Persistent hyperglycemia has caused damage on various organs, including the heart, kidney, and retina. Microvascular complications are the most common complications of diabetes and mainly include diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy [6]. Of the 10 leading causes of death among adults, diabetes has become the most common endocrine-metabolic disease [7]. Globally, in 2019, 463 million people were predicted to have diabetes, of whom 9.3% would be adults aged 20-79 years; this number is expected to reach 578 million (10.2%) by 2030 and increase by 1.5 times over 25 years [8]. Our previous research demonstrated that MSC-exos can alleviate type 2 diabetes by reversing peripheral insulin resistance and relieving β-cells destruction [9]. Other studies have reported that MSC-exos can regulate the pathophysiological process of diabetes and its microvascular complications by transferring proteins, nucleotides, and other signaling molecules. Currently, how MSC-exos maintain blood glucose homeostasis and delay the progression of diabetic microvascular complications remain unclear. Therefore, we reviewed the progress and relevant mechanisms of MSC-exos with regard to their therapeutic potential for diabetes and its microvascular complications. In particular, we aimed to elucidate mechanisms through which MSC-exos improve islet β-cell viability, insulin resistance, diabetic nephropathy, and retinopathy.

Characteristics of MSC-exos

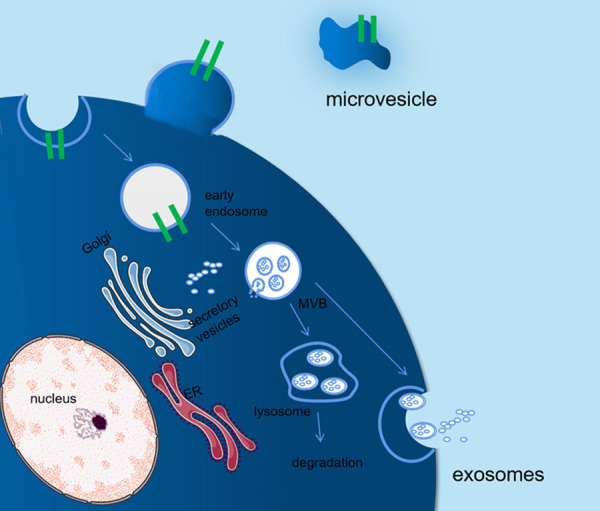

MSCs are a type of multipotent, nonhematopoietic, stromal precursor cells with self-renewal and multidirectional differentiation abilities [10,11]. MSCs are distributed throughout the body; they can be isolated from not only mature tissues, such as the adipose tissue, gums, and pancreas, but also other sources, including the amniotic fluid, umbilical cord, and placenta [12]. Both properties of MSCs, namely self-renewal and multidirectional differentiation, promote tissue repair and regeneration [13,14]. In addition, MSCs can secrete various cytokines and even exosomes [15-17] to regulate T cells, B cells, natural killer cells and dendritic cells, and participate in innate and adaptive immunity [18-25]. After the induction of pancreatic MSCs, insulin-secreting β-like islet cells were formed to maintain blood glucose homeostasis in diabetic mice [26]. Umbilical cord MSC-conditioned medium (MSC-CM) contains various components that can improve insulin resistance through multiple mechanisms [27]. Extracellular vesicles can be categorized as apoptotic bodies, microvesicles (MVs), and exosomes [28]. Apoptotic bodies are related to programmed cell death. As shown in Figure 1, MVs are formed from the exocytosis of the plasma membrane and range from 50 to 1000 nm in size. MVs with irregular shapes mainly contain cytoplasmic materials. By contrast, exosomes are formed from the endocytosis of the plasma membrane, followed by the fusion of a multivesicular body and secondary exocytosis; exosomes range from 40 to 200 nm in size [29,30]. The surface proteins of MVs mainly originate from the membranes of cells from which they are derived, and exosomes include CD63, CD81, and CD9 [31]. Because of their similar sizes and limited experimental conditions, it is difficult to distinguish MVs [1,28].

Figure 1.

Formation of exosomes and microvesicles. Microvesicles (MVs) with irregular shapes are formed from the exocytosis of the plasma membrane and mainly contain cytoplasmic materials. By contrast, exosomes are formed from the endocytosis of the plasma membrane followed by the fusion of a multivesicular body and secondary exocytosis; the sizes of exosomes are smaller than those of MVs. The surface proteins of MVs mainly originate from the membranes of cells from which they are derived, and exosomes include CD63, CD81, and CD9.

Cellular crosstalk resulting from the exchange of cellular components mediated by exosomes may be a novel type of intercellular communication [32]. Exosomes, with their cargo, can initiate various physiological responses in a recipient cell by interacting with its receptors [33] and mediating signal transduction pathways [34-36].

MSC-exos in the maintenance of blood glucose homeostasis

MSC-exos and pancreatic β-cells

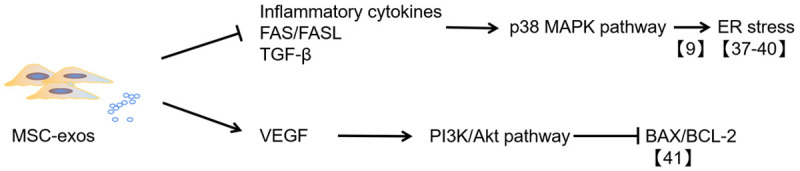

Impaired β-cell function is crucial in the progression of both type 1 and 2 diabetes. The substantial loss of β-cells in the adverse outcome of long-term insulin dependence. Therefore, reversing β-cell injury and even regenerating β-cells are the ultimate goals of diabetes treatment. As shown in Table 1, many studies have suggested that MSCs can regulate immune inflammatory responses by exosomes, inhibit endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and β-cell apoptosis, and restore the function of pancreatic islets to varying degrees (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Effect of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells on improving β-cell function

| Model | Source | Exosome | Route | Effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STZ-induced | MenSCs | NG | In vivo Intravenously injection | Regenerate β islets through Pdx-1 dependent mechanism | [37] |

| hypoxia-induced | HucMSC | miR-21 | in vitro | Alleviate ER stress and inhibiting p38 MAPK phosphorylation | [38] |

| STZ-induced | BMSCs | shFas and anti-miR-375 | In vitro | Downregulate Expression of Fas and miR-375 in Human Islets | [39] |

| STZ-induced | AD-MSCs | NG | In vivo intraperitoneal injection | increase regulatory T-cell population and their products | [40] |

| HFD and STZ | HucMSC | GLUT; PK and LDH etc. | In vivo Intravenously injection | decrease caspase3 | [9] |

| Isolated mouse islets | MSC | VEGF | In vitro | Activate PI3K/Akt pathway Decrease BAD and BAX Increase BCL-2 Downregulate BAX/BCL-2 | [41] |

STZ: streptozotocin; HFD: high-fat diet; HucMSCs: human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells; MenSCs: menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells; BMSCs: bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; AD-MSCs: adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells; NG: not given; GLUT: glucose transporters; PK: pyruvate kinase; LDH: lactic dehydrogenase; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

Figure 2.

The mechanism of anti-β cell apoptosis mediated by MSC-exos. MSC-exos can improve β-cell viability by downregulating ER stress and apoptosis-related proteins, such as BAX/BCL-2, through the repression of the p38 MAPK pathway and activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway.

Streptozotocin (STZ) was usually used to induce β-cell destruction in rats. Menstrual blood-derived MSC-exos were injected into the tail vein of STZ-treated animals at different time points (0, 2, or 10 days after STZ injection) in a single or repeated dose. The results suggested that all therapeutic methods could increase the number of islets after approximately 6 weeks as soon as β-cells were damaged. However, the number of islets did not differ significantly between the repeated-dose and single-dose groups. The size of regenerated islets was smaller in all experimental mice compared with nondiabetic mice; however, the size of regenerated islets of the repeated-dose group was larger. Although the plasma insulin levels of mice that received MSC-exo treatment were higher than those of controls, little statistical difference was detected in the fasting blood glucose (FBG) level between the treatment and nontreatment groups. Glucose levels may not have been improved because of the following reasons: detection of proinsulin instead of its active form, inadequate regeneration of β-cells, or immaturity of regenerated islets [37].

A study indicated that hypoxia could significantly induce β-cell apoptosis. β-cells were cultured under the condition of hypoxia (2% oxygen) with or without umbilical cord MSC-exos. The concentrations of exosomes were varied (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL). The results indicated that low-dose MSC-exos (6.25 and 12.5 μg/mL) could not improve β-cell viability, but high-dose exosomes (25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) significantly promoted β-cell survival under hypoxic conditions. MSC-exos can inhibit ER stress and apoptotic signal pathways in hypoxic environment. Moreover, the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal pathway was suppressed by MSC-exos with miR-21 and let-7g. After transfection with an miR-21 mimic, ER stress and the p38 MAPK signal pathway were downregulated in β-cells under a hypoxic condition, and the survival rate of β-cells increased, which could be reversed by exosomes with an miR-21 inhibitor [38].

Bone marrow MSC (BMSC)-exos transfected with pshFas-anti-miR-375 could downregulate Fas and miR-375 levels, inhibit β-cells apoptosis, and relieve islet damage against inflammatory cytokines [39]. A study suggested that adipose-derived MSC (AD-MSC)-exos can upregulate interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β; reduce IL-17 and interferon gamma, and upregulate the regulatory T cell ratio in splenic mononuclear cells of mice with type 1 diabetes mellitus. An obvious increase in the number of islets was observed after the application of AD-MSC-exos, which can be attributed to the amelioration of autoimmunity [40]. Even in a model of type 2 diabetes induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) and STZ, our previous study [9] demonstrated that human umbilical cord MSC (HucMSC)-exos not only accelerated glucose metabolism by improving insulin sensitivity but also inhibited β-cell apoptosis and partly restored the insulin secretion function of islets. Furthermore, a recent study reported that MSC-exos with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) could preserve islet survival and insulin secretion function in vitro through the PI3K/Akt pathway [41].

MSC-exos and insulin resistance

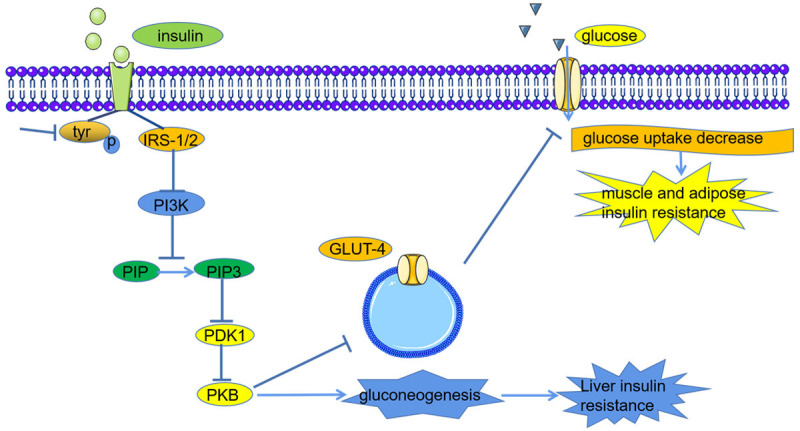

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by insulin resistance and defective β-cells function [42]. As shown in Figure 3, insulin resistance is mainly caused by the obstruction of insulin signal transduction, which is due to the disordered phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and the inactivation of protein kinase B (PKB) [43-45]. HucMSC-exos were intravenously injected into mice with type 2 diabetes induced by HFD and STZ. The FBG of the mice significantly decreased [46]. HucMSC-exos could not only significantly promote liver glycolysis and glycogen synthesis and inhibit gluconeogenesis but also induce the phosphorylation of tyrosine in IRS-1 and PKB and increase the synthesis and membrane translocation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT-4) in the muscle tissue [9]. Therefore, HucMSC-exos can improve insulin sensitivity and maintain glucose homeostasis.

Figure 3.

The mechanism of insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. The high glucose level causes the disordered phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and the inactivation of protein kinase B (PKB), which lead to liver insulin resistance by promoting the process of gluconeogenesis. The disordered expression and translocation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) contribute to muscle and adipose insulin resistance.

Type 2 diabetes is closely associated with age, and its incidence is generally higher in the older population than in the younger population. A study suggested a remarkable increase in miR-29b-3p levels in the hBMSC-exos of older mice. The upregulation of miR-29b-3p in hBMSC-exos significantly increased the risk of insulin resistance, and sirtuin 1, as the downstream target, also played a crucial role in the regulation of insulin resistance. The study revealed that miR-29b-3p in hBMSC-exos could be a promising target for improving aging-associated insulin resistance [47].

MSC-exos in diabetic microvascular complications

MSC-exos and diabetic kidney disease

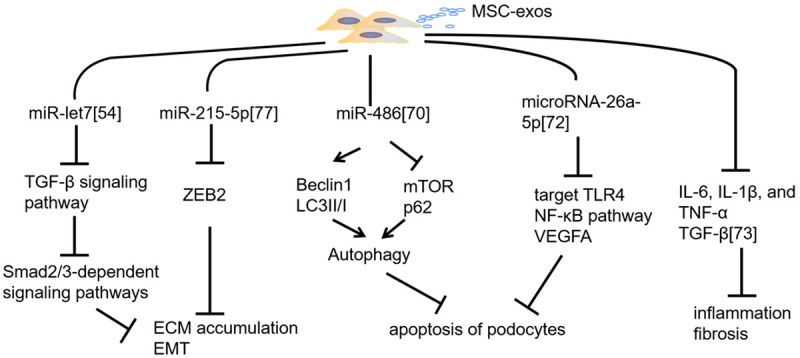

Diabetic nephropathy (DN), also known as glomerulosclerosis, can present as diffuse or nodular glomerulosclerosis as well as renal interstitial fibrosis, renal arteriolar sclerosis, and renal tubular disease [48,49]. Various kidney diseases, including DN, are related to miRNA abnormalities [50]. Related studies have indicated that miRNAs are indispensable in both renal fibrosis and antifibrosis [51-53]. MiRNAs can be transported by exosomes and promote corresponding changes in target cells. In a mouse model of renal fibrosis, miR-let7c was transported to the impaired kidney by MSC-exos. miR-let7c upregulation was accompanied by the amelioration of the renal structure and the reduction of extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition through the inhibition of type 1α1 and IVα1 collagen, TGF-β type 1 receptor, and α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) [54]. The TGF-β signaling pathway is crucial in the pathophysiology of renal fibrosis. This signaling pathway not only aggravates the deposition of ECM molecules, such as collagen type I, α-SMA, and laminin [55,56], but also is related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [57,58]; these factors contribute to the progression of renal fibrosis [59]. TGF-β1 mainly functions on the downstream Smad2/3-dependent signal pathway to induce the transdifferentiation of intrinsic renal cells [60]. The Smad2/3-dependent signal pathway, which involves MAPKs [61], Ras homolog family member A [62], and Wnt/β-catenin [63], can accelerate the progression of renal fibrosis. Nagaishi et al. designed an experiment revealing that exosomes purified from MSC conditioned medium (MSC-CM) could ameliorate vacuolation, atrophic change, and apoptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) by inhibiting the TGF-β1 signaling pathway and maintain the expression of cellular junction proteins such as zona occludens protein 1 (ZO-1) in Bowman’s capsule and TECs [64]. Moreover, because of the deposition of ECM proteins, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have been identified as targets for potential kidney fibrosis treatment [65]. This process was affirmed by another study in which mouse ucMSC-derived paracrine factors reduced the deposition of ECM proteins by inhibiting myofibroblast transdifferentiation induced by TGF-β1, cell proliferation mediated by the Smad2/3-dependent signaling pathway, and the upregulation of MMP2 and MMP9 [66]. Moreover, the antifibrotic properties of MSC-derived paracrine in DN might depend on exosomes secreted by MSCs [66].

The clinical characteristics of DN mainly manifest as persistent albuminuria. Pathologically, DN mainly manifests as a thickening of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and increased mesangial matrix, which are associated with autophagic flux inhibition, podocyte apoptosis or necrosis, and renal function exacerbation [67]. Autophagic dysfunction is a sign of podocyte apoptosis or necrosis [68]. Persistent hyperglycemia can downregulate the expression of autophagy-related proteins, such as Beclin 1 and LC3II/I, and increase the phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and the p62 level, which can downregulate autophagy and accelerate podocyte injury in patients with DN [69,70]. AD-MSC-exos could reduce the levels of blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and urine protein and inhibit podocyte apoptosis in mice, with miR-486 playing a crucial role [70]. miR-486 contained in AD-MSC-exos can downregulate Smad1 expression, thereby repressing mTOR pathway activation, promoting autophagy, and inhibiting podocyte apoptosis [70]. Moreover, exosomes from BMSCs significantly restored renal function and structure by increasing autophagy-related protein and prominently reducing mTOR in the renal tissue [71]. Duan et al. [72] also demonstrated that microRNA-26a-5p carried by the extracellular vesicles of AD-MSCs can target Toll-like receptor 4, deactivate the nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway, downregulate vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), and inhibit the apoptosis of mouse glomerular podocytes to prevent DN. In vitro experiments by Xiang et al. [73] indicated that HucMSC-exos and HucMSCs can repress proinflammatory cytokine and profibrotic factor levels in renal glomerular endothelial cells and TECs, thus preventing early DN.

Researchers have demonstrated that EMT is a feature of hyperglycemia-induced podocyte injury, which is regarded as the initiating factor of GBM thickening and persistent albuminuria [74,75]. Zinc finger E box-binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2), a DNA-binding transcription factor, is associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration, and invasion [76]. AD-MSC-exos can transfer miR-215-5p to podocytes and prevent hyperglycemia-induced EMT by means of ZEB2 inhibition [77] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mechanism of preventing DN progression mediated by MSC-exos. MSC-exos with miR-let7 and miR-215-5p can inhibit the deposition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by downregulating the TGF-β signaling pathway and Zinc finger E box-binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2); MSC-exos with miR-486 and microRNA-26a-5p can repress the apoptosis of podocytes through autophagy activation and the downregulation of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway; in addition, they can repress proinflammatory cytokine and profibrotic factor levels to prevent early diabetic nephropathy (DN).

MSC-exos and diabetic retinopathy

Retinal ischemia and inflammation are pathophysiological hallmarks of vision loss and injury in diabetic retinopathy (DR) [78,79]. Mathew et al. revealed the neuroprotective effect of MSCs and MSC-CM in a mouse retinal ischemia-reperfusion model and verified that the effect was achieved through exosomes [80-82]. In a rat ischemia model, MSC exosomes were injected into the vitreous humor 24 h after retinal ischemia, and MSC-exos were absorbed by retinal ganglion cells, neurons, and microglia through cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan; however, they remained in the vitreous humor for 4 weeks. MSC-exo treatment ameliorated the impairment of function, neuroinflammation, and cell apoptosis [83].

In vivo, MSC-exos with miR-126 were intravitreally injected into diabetic rats, and MSC-exos were cultured in vitro with high glucose-conditioned human retinal endothelial cells (HRECs) [84]. The results suggested that inflammation in vivo and in vitro could be promoted by high glucose via inflammatory cytokine upregulation, which could be reversed by miR-126 carried by MSC-exos by inhibiting the high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) signaling pathway, inflammation, and nod-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome activity in HRECs [84]. In another study, high glucose-treated Muller cells were cocultured with BMSC-exos with miR-486-3p, and the results showed that the expression of miR-486-3p could improve the proliferation of Muller cells due to the inhibition of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway and the alleviation of oxidative stress [85].

Angiogenesis is an indicator of the DR severity. The miR-221/miR-222 family could repress angiogenesis through the c-Kit receptor [86] and regulate signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A (STAT5A) during neoangiogenesis-related inflammation [87]. The results affirmed that micRNA-222 carried by MSC-exos could promote retina regeneration [88]. Therefore, the exosomes released by MSCs have been considered novel therapeutic vectors because of their role in shuttling signal factors [88].

Conclusions

Current treatments for diabetes mainly encompass drug therapy, such as oral antidiabetic drugs, and insulin therapy, such as subcutaneous injections and subcutaneous and intravenous pumping. However, these treatments require long-term follow-up and blood glucose adjustment. They cannot fundamentally cure diabetes or its complications in the long term. Studies have indicated that MSC-exos with different cargo can improve or even reverse the pathophysiology of diabetes and its microvascular complications through various pathways. MSC-exos might be novel promising vectors for the treatment of diabetes and its microvascular complications. However, more questions regarding the duration, dosage, and safety of MSC-exo treatment for diabetes and its complications warrant further study.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81702439, 81802446); Tai Shan Young Scholar Foundation of Shandong Province (NO. tsqn201909192); Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2019BH050); PhD Research Foundation of Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University (No. 2018-BS-001, 2018-BS-013); Academician Lin He New Medicine (NO. JYHL2018FMS04); and Teachers’ research of Jining Medical University (NO. JYFC2018FKJ035).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Wang WT, Gong CR, Li C, Shi M. Combination of olfactory ensheathing cells and human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promotes sciatic nerve regeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15:1903–1911. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.280330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H, Xie Y, Salvador AM, Zhang Z, Chen K, Li G, Xiao J. Exosomes: multifaceted messengers in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020;22:57. doi: 10.1007/s11883-020-00871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu M, Liu X, Li W, Wang L. Exosomes derived from mmu_circ_0000623-modified ADSCs prevent liver fibrosis via activating autophagy. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2020;39:1619–1627. doi: 10.1177/0960327120931152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jayaramayya K, Mahalaxmi I, Subramaniam MD, Raj N, Dayem AA, Lim KM, Kim SJ, An JY, Lee Y, Choi Y, Raj A, Cho SG, Vellingiri B. Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells and mesenchymal stem-cell-derived exosomes for COVID-19 treatment. BMB Rep. 2020;53:400–412. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2020.53.8.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadini GP, Ferraro F, Quaini F, Asahara T, Madeddu P. Concise review: diabetes, the bone marrow niche, and impaired vascular regeneration. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:949–957. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu X, Zhao C. Exercise and type 1 diabetes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1228:107–121. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, Colagiuri S, Guariguata L, Motala AA, Ogurtsova K, Shaw JE, Bright D, Williams R IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Y, Shi H, Yin S, Ji C, Zhang X, Zhang B, Wu P, Shi Y, Mao F, Yan Y, Xu W, Qian H. Human mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes alleviate type 2 diabetes mellitus by reversing peripheral insulin resistance and relieving beta-cell destruction. ACS Nano. 2018;12:7613–7628. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b07643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang D, Gao F, Zhang Y, Wong DS, Li Q, Tse HF, Xu G, Yu Z, Lian Q. Mitochondrial transfer of mesenchymal stem cells effectively protects corneal epithelial cells from mitochondrial damage. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2467. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seo Y, Kim HS, Hong IS. Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles as immunomodulatory therapeutics. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:5126156. doi: 10.1155/2019/5126156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DE, Ayoub N, Agrawal DK. Mesenchymal stem cells and cutaneous wound healing: novel methods to increase cell delivery and therapeutic efficacy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:37. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0303-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao L, Peng Y, Xu W, He P, Li T, Lu X, Chen G. Progress in stem cell therapy for spinal cord injury. Stem Cells Int. 2020;2020:2853650. doi: 10.1155/2020/2853650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romanelli P, Bieler L, Scharler C, Pachler K, Kreutzer C, Zaunmair P, Jakubecova D, Mrowetz H, Benedetti B, Rivera FJ, Aigner L, Rohde E, Gimona M, Strunk D, Couillard-Despres S. Extracellular vesicles can deliver anti-inflammatory and anti-scarring activities of mesenchymal stromal cells after spinal cord injury. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1225. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mardpour S, Hamidieh AA, Taleahmad S, Sharifzad F, Taghikhani A, Baharvand H. Interaction between mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles and immune cells by distinct protein content. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:8249–8258. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarez MV, Gutierrez LM, Correa A, Lazarowski A, Bolontrade MF. Metastatic niches and the modulatory contribution of mesenchymal stem cells and its exosomes. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:17. doi: 10.3390/ijms20081946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao V, Thakur S, Rao J, Arakeri G, Brennan PA, Jadhav S, Sayeed MS, Rao G. Mesenchymal stem cells-bridge catalyst between innate and adaptive immunity in COVID 19. Med Hypotheses. 2020;143:109845. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo H, Su Y, Deng F. Effects of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles in lung diseases: current status and future perspectives. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020;19:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s12015-020-10085-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Xia J, Huang R, Hu Y, Fan J, Shu Q, Xu J. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles alter disease outcomes via endorsement of macrophage polarization. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:424. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01937-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JH, Liu XL, Sun JM, Yang JH, Xu DH, Yan SS. Role of mesenchymal stem cell derived extracellular vesicles in autoimmunity: a systematic review. World J Stem Cells. 2020;12:879–896. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i8.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang JH, Liu FX, Wang JH, Cheng M, Wang SF, Xu DH. Mesenchymal stem cells and mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: potential roles in rheumatic diseases. World J Stem Cells. 2020;12:688–705. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i7.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee BC, Yu KR. Impact of mesenchymal stem cell senescence on inflammaging. BMB Rep. 2020;53:65–73. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2020.53.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi Y, Wang Y, Li Q, Liu K, Hou J, Shao C, Wang Y. Immunoregulatory mechanisms of mesenchymal stem and stromal cells in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:493–507. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Santalla M, Fernandez-Perez R, Garin MI. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells for rheumatoid arthritis treatment: an update on clinical applications. Cells. 2020;9:1852. doi: 10.3390/cells9081852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang S, Yin J, Ji H, Wang Q, Yang Q, Lai J, Sun Y, Guan W, Chen P. Functional β-cell differentiation of small-tail han sheep pancreatic mesenchymal stem cells and the therapeutic potential in type 1 diabetic mice. Pancreas. 2020;49:947–954. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim KS, Choi YK, Kim MJ, Hwang JW, Min K, Jung SY, Kim SK, Choi YS, Cho YW. Umbilical cord-mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium improves insulin resistance in C2C12 cell. Diabetes Metab J. 2020 doi: 10.4093/dmj.2019.0191. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castaño C, Novials A, Párrizas M. Exosomes and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019;35:e3107. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, Buzas K, Casal E, Cappello F, Carvalho J, Colás E, Cordeiro-da Silva A, Fais S, Falcon-Perez JM, Ghobrial IM, Giebel B, Gimona M, Graner M, Gursel I, Gursel M, Heegaard NH, Hendrix A, Kierulf P, Kokubun K, Kosanovic M, Kralj-Iglic V, Krämer-Albers EM, Laitinen S, Lässer C, Lener T, Ligeti E, Linē A, Lipps G, Llorente A, Lötvall J, Manček-Keber M, Marcilla A, Mittelbrunn M, Nazarenko I, Nolte-’t Hoen EN, Nyman TA, O’Driscoll L, Olivan M, Oliveira C, Pállinger É, Del Portillo HA, Reventós J, Rigau M, Rohde E, Sammar M, Sánchez-Madrid F, Santarém N, Schallmoser K, Ostenfeld MS, Stoorvogel W, Stukelj R, Van der Grein SG, Vasconcelos MH, Wauben MH, De Wever O. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nawaz M, Camussi G, Valadi H, Nazarenko I, Ekström K, Wang X, Principe S, Shah N, Ashraf NM, Fatima F, Neder L, Kislinger T. The emerging role of extracellular vesicles as biomarkers for urogenital cancers. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:688–701. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anthony DF, Shiels PG. Exploiting paracrine mechanisms of tissue regeneration to repair damaged organs. Transplant Res. 2013;2:10. doi: 10.1186/2047-1440-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiu G, Zheng G, Ge M, Wang J, Huang R, Shu Q, Xu J. Functional proteins of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:359. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1484-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simpson RJ, Lim JW, Moritz RL, Mathivanan S. Exosomes: proteomic insights and diagnostic potential. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2009;6:267–283. doi: 10.1586/epr.09.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomou T, Mori MA, Dreyfuss JM, Konishi M, Sakaguchi M, Wolfrum C, Rao TN, Winnay JN, Garcia-Martin R, Grinspoon SK, Gorden P, Kahn CR. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature. 2017;542:450–455. doi: 10.1038/nature21365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Müller G, Schneider M, Biemer-Daub G, Wied S. Microvesicles released from rat adipocytes and harboring glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins transfer RNA stimulating lipid synthesis. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1207–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferguson SW, Wang J, Lee CJ, Liu M, Neelamegham S, Canty JM, Nguyen J. The microRNA regulatory landscape of MSC-derived exosomes: a systems view. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1419. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19581-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahdipour E, Salmasi Z, Sabeti N. Potential of stem cell-derived exosomes to regenerate beta islets through Pdx-1 dependent mechanism in a rat model of type 1 diabetes. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:20310–20321. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Chen J, Cheng Y, Fu Y, Zhao H, Tang M, Zhao H, Lin N, Shi X, Lei Y, Wang S, Huang L, Wu W, Tan J. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes protect beta cells against hypoxia-induced apoptosis via miR-21 by alleviating ER stress and inhibiting p38 MAPK phosphorylation. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:97. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01610-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wen D, Peng Y, Liu D, Weizmann Y, Mahato RI. Mesenchymal stem cell and derived exosome as small RNA carrier and immunomodulator to improve islet transplantation. J Control Release. 2016;238:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nojehdehi S, Soudi S, Hesampour A, Rasouli S, Soleimani M, Hashemi SM. Immunomodulatory effects of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes on experimental type-1 autoimmune diabetes. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:9433–9443. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keshtkar S, Kaviani M, Sarvestani FS, Ghahremani MH, Aghdaei MH, Al-Abdullah IH, Azarpira N. Exosomes derived from human mesenchymal stem cells preserve mouse islet survival and insulin secretion function. EXCLI J. 2020;19:1064–1080. doi: 10.17179/excli2020-2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mezza T, Cinti F, Cefalo CMA, Pontecorvi A, Kulkarni RN, Giaccari A. β-cell fate in human insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: a perspective on islet plasticity. Diabetes. 2019;68:1121–1129. doi: 10.2337/db18-0856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rabiee A, Krüger M, Ardenkjær-Larsen J, Kahn CR, Emanuelli B. Distinct signalling properties of insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 and IRS-2 in mediating insulin/IGF-1 action. Cell Signal. 2018;47:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chakraborty C, Doss CG, Bandyopadhyay S, Agoramoorthy G. Influence of miRNA in insulin signaling pathway and insulin resistance: micro-molecules with a major role in type-2 diabetes. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2014;5:697–712. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Si Y, Zhao Y, Hao H, Liu J, Guo Y, Mu Y, Shen J, Cheng Y, Fu X, Han W. Infusion of mesenchymal stem cells ameliorates hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetic rats: identification of a novel role in improving insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2012;61:1616–1625. doi: 10.2337/db11-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He Q, Wang L, Zhao R, Yan F, Sha S, Cui C, Song J, Hu H, Guo X, Yang M, Cui Y, Sun Y, Sun Z, Liu F, Dong M, Hou X, Chen L. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes exert ameliorative effects in type 2 diabetes by improving hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism via enhancing autophagy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:223. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01731-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 47.Su T, Xiao Y, Xiao Y, Guo Q, Li C, Huang Y, Deng Q, Wen J, Zhou F, Luo XH. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomal miR-29b-3p regulates aging-associated insulin resistance. ACS Nano. 2019;13:2450–2462. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b09375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.A/L B Vasanth Rao VR, Tan SH, Candasamy M, Bhattamisra SK. Diabetic nephropathy: an update on pathogenesis and drug development. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:754–762. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Najafian B, Alpers CE, Fogo AB. Pathology of human diabetic nephropathy. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;170:36–47. doi: 10.1159/000324942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandrasekaran K, Karolina DS, Sepramaniam S, Armugam A, Wintour EM, Bertram JF, Jeyaseelan K. Role of microRNAs in kidney homeostasis and disease. Kidney Int. 2012;81:617–627. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srivastava SP, Hedayat AF, Kanasaki K, Goodwin JE. MicroRNA crosstalk influences epithelial-to-mesenchymal, endothelial-to-mesenchymal, and macrophage-to-mesenchymal transitions in the kidney. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:904. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grange C, Tritta S, Tapparo M, Cedrino M, Tetta C, Camussi G, Brizzi MF. Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles inhibit and revert fibrosis progression in a mouse model of diabetic nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4468. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41100-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zanchi C, Macconi D, Trionfini P, Tomasoni S, Rottoli D, Locatelli M, Rudnicki M, Vandesompele J, Mestdagh P, Remuzzi G, Benigni A, Zoja C. MicroRNA-184 is a downstream effector of albuminuria driving renal fibrosis in rats with diabetic nephropathy. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1114–1125. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4248-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang B, Yao K, Huuskes BM, Shen HH, Zhuang J, Godson C, Brennan EP, Wilkinson-Berka JL, Wise AF, Ricardo SD. Mesenchymal stem cells deliver exogenous microRNA-let7c via exosomes to attenuate renal fibrosis. Mol Ther. 2016;24:1290–1301. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sugimoto H, LeBleu VS, Bosukonda D, Keck P, Taduri G, Bechtel W, Okada H, Carlson W Jr, Bey P, Rusckowski M, Tampe B, Tampe D, Kanasaki K, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Activin-like kinase 3 is important for kidney regeneration and reversal of fibrosis. Nat Med. 2012;18:396–404. doi: 10.1038/nm.2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hills CE, Squires PE. The role of TGF-β and epithelial-to mesenchymal transition in diabetic nephropathy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzalez DM, Medici D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci Signal. 2014;7:re8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jin J, Gong J, Zhao L, Zhang H, He Q, Jiang X. Inhibition of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) attenuates podocyte apoptosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by regulating autophagy flux. J Diabetes. 2019;11:826–836. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vega G, Alarcon S, San Martin R. The cellular and signalling alterations conducted by TGF-beta contributing to renal fibrosis. Cytokine. 2016;88:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu X, Gao Y, Xu L, Dang W, Yan H, Zou D, Zhu Z, Luo L, Tian N, Wang X, Tong Y, Han Z. Exosomes from high glucose-treated glomerular endothelial cells trigger the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and dysfunction of podocytes. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9371. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09907-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang S, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, He X, Zhao X, Zhao H, Liu W. Roscovitine attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis in diabetic mice through the TGF-beta1/p38 MAPK pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;115:108895. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie X, Peng J, Chang X, Huang K, Huang J, Wang S, Shen X, Liu P, Huang H. Activation of RhoA/ROCK regulates NF-kappaB signaling pathway in experimental diabetic nephropathy. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;369:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X, Liu Y, Shao R, Li W. Cdc42-interacting protein 4 silencing relieves pulmonary fibrosis in STZ-induced diabetic mice via the Wnt/GSK-3beta/beta-catenin pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2017;359:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagaishi K, Mizue Y, Chikenji T, Otani M, Nakano M, Konari N, Fujimiya M. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy ameliorates diabetic nephropathy via the paracrine effect of renal trophic factors including exosomes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34842. doi: 10.1038/srep34842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parrish AR. Matrix metalloproteinases in kidney disease: role in pathogenesis and potential as a therapeutic target. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2017;148:31–65. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li H, Rong P, Ma X, Nie W, Chen Y, Zhang J, Dong Q, Yang M, Wang W. Mouse umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell paracrine alleviates renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy by reducing myofibroblast transdifferentiation and cell proliferation and upregulating MMPs in mesangial cells. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:3847171. doi: 10.1155/2020/3847171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang L, Li R, Shi W, Liang X, Liu S, Ye Z, Yu C, Chen Y, Zhang B, Wang W, Lai Y, Ma J, Li Z, Tan X. NFAT2 inhibitor ameliorates diabetic nephropathy and podocyte injury in db/db mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:426–439. doi: 10.1111/bph.12292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yi M, Zhang L, Liu Y, Livingston MJ, Chen JK, Nahman NS Jr, Liu F, Dong Z. Autophagy is activated to protect against podocyte injury in adriamycin-induced nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;313:F74–F84. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00114.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu L, Feng Z, Cui S, Hou K, Tang L, Zhou J, Cai G, Xie Y, Hong Q, Fu B, Chen X. Rapamycin upregulates autophagy by inhibiting the mTOR-ULK1 pathway, resulting in reduced podocyte injury. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jin J, Shi Y, Gong J, Zhao L, Li Y, He Q, Huang H. Exosome secreted from adipose-derived stem cells attenuates diabetic nephropathy by promoting autophagy flux and inhibiting apoptosis in podocyte. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:95. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ebrahim N, Ahmed IA, Hussien NI, Dessouky AA, Farid AS, Elshazly AM, Mostafa O, Gazzar WBE, Sorour SM, Seleem Y, Hussein AM, Sabry D. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorated diabetic nephropathy by autophagy induction through the mTOR signaling pathway. Cells. 2018;7:226. doi: 10.3390/cells7120226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duan Y, Luo Q, Wang Y, Ma Y, Chen F, Zhu X, Shi J. Adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles containing microRNA-26a-5p target TLR4 and protect against diabetic nephropathy. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:12868–12884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.012522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xiang E, Han B, Zhang Q, Rao W, Wang Z, Chang C, Zhang Y, Tu C, Li C, Wu D. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells prevent the progression of early diabetic nephropathy through inhibiting inflammation and fibrosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:336. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01852-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li Y, Kang YS, Dai C, Kiss LP, Wen X, Liu Y. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is a potential pathway leading to podocyte dysfunction and proteinuria. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:299–308. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ying Q, Wu G. Molecular mechanisms involved in podocyte EMT and concomitant diabetic kidney diseases: an update. Ren Fail. 2017;39:474–483. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2017.1313164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fardi M, Alivand M, Baradaran B, Farshdousti Hagh M, Solali S. The crucial role of ZEB2: from development to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cancer complexity. J Cell Physiol. 2019 doi: 10.1002/jcp.28277. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jin J, Wang Y, Zhao L, Zou W, Tan M, He Q. Exosomal miRNA-215-5p derived from adipose-derived stem cells attenuates epithelial-mesenchymal transition of podocytes by inhibiting ZEB2. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:2685305. doi: 10.1155/2020/2685305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rivera JC, Dabouz R, Noueihed B, Omri S, Tahiri H, Chemtob S. Ischemic retinopathies: oxidative stress and inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:3940241. doi: 10.1155/2017/3940241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Duh EJ, Sun JK, Stitt AW. Diabetic retinopathy: current understanding, mechanisms, and treatment strategies. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e93751. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roth S, Dreixler JC, Mathew B, Balyasnikova I, Mann JR, Boddapati V, Xue L, Lesniak MS. Hypoxic-preconditioned bone marrow stem cell medium significantly improves outcome after retinal ischemia in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:3522–3532. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dreixler JC, Poston JN, Balyasnikova I, Shaikh AR, Tupper KY, Conway S, Boddapati V, Marcet MM, Lesniak MS, Roth S. Delayed administration of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium significantly improves outcome after retinal ischemia in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:3785–3796. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mathew B, Poston JN, Dreixler JC, Torres L, Lopez J, Zelkha R, Balyasnikova I, Lesniak MS, Roth S. Bone-marrow mesenchymal stem-cell administration significantly improves outcome after retinal ischemia in rats. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;255:1581–1592. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3690-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mathew B, Ravindran S, Liu X, Torres L, Chennakesavalu M, Huang CC, Feng L, Zelka R, Lopez J, Sharma M, Roth S. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles and retinal ischemia-reperfusion. Biomaterials. 2019;197:146–160. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang W, Wang Y, Kong Y. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells modulate miR-126 to ameliorate hyperglycemia-induced retinal inflammation via targeting HMGB1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:294–303. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li W, Jin L, Cui Y, Nie A, Xie N, Liang G. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-induced exosomal microRNA-486-3p protects against diabetic retinopathy through TLR4/NF-κB axis repression. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01405-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Poliseno L, Tuccoli A, Mariani L, Evangelista M, Citti L, Woods K, Mercatanti A, Hammond S, Rainaldi G. MicroRNAs modulate the angiogenic properties of HUVECs. Blood. 2006;108:3068–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-012369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dentelli P, Rosso A, Orso F, Olgasi C, Taverna D, Brizzi MF. microRNA-222 controls neovascularization by regulating signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1562–1568. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.206201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Safwat A, Sabry D, Ragiae A, Amer E, Mahmoud RH, Shamardan RM. Adipose mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes attenuate retina degeneration of streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rabbits. J Circ Biomark. 2018;7:1849454418807827. doi: 10.1177/1849454418807827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]