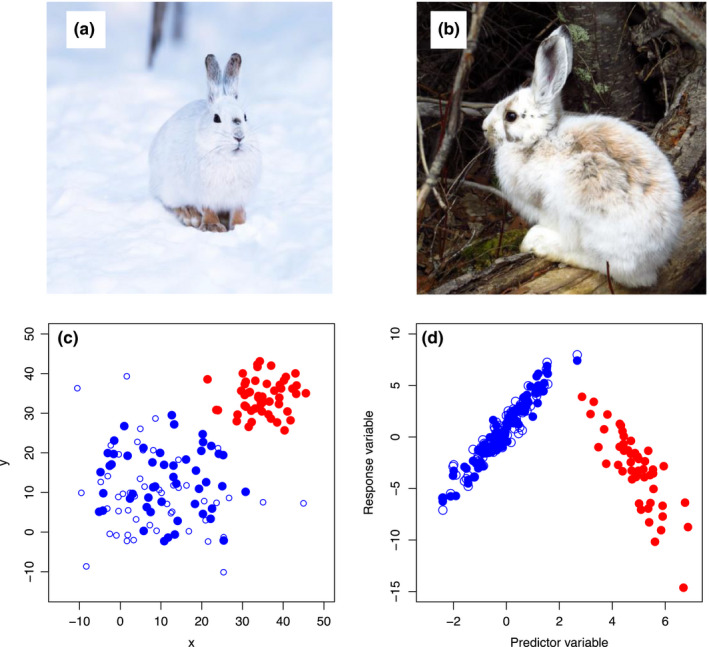

FIGURE 1.

Understanding mechanisms often increases model transferability. Panels (a and b) show snowshoe hares in winter and summer coloration, respectively. If a correlative (i.e., nonmechanistic) model for hare survival as a function of color was trained only on hares during the winter and then extrapolated into the summer months, it would perform poorly (white hares would die disproportionately under no‐snow conditions). On the other hand, a researcher testing mechanisms for hare survival would (ideally via experimentation) arrive at the conclusion that it is not the whiteness of hares, but rather blending with the background that confers survival (the “camouflage” hypothesis). Understanding mechanism results in model predictions being robust to novel conditions. Panel (c) Shows x and y geographic locations of training (blue filled circles) and testing (blue open circles) locations for a hypothetical correlative model. Even if the model performs well on these independent test data (predicting open to closed circles), there is no guarantee that it will predict well outside of the spatial bounds of the existing data (red circles). Nonstationarity (in this case caused by a nonlinear relationship between predictor and response variable; panel d) could result in correlative relationships shifting substantially if extrapolated to new times or places. However, mechanistic hypotheses aimed at understanding the underlying factors driving the distribution of this species would be more likely to elucidate this nonlinear relationship. In both of these examples, understanding drivers behind ecological patterns—via testing mechanistic hypotheses—is likely to enhance model transferability