S. wittichii RW1 has been the subject of numerous investigations, because it is one of only a few strains known to grow on DXN as the sole carbon and energy source. However, while the genome has been sequenced and several DBF pathway enzymes have been purified, there has been very little research using physiological techniques to precisely identify the genes and enzymes involved in the RW1 DBF and DXN catabolic pathways.

KEYWORDS: biodegradation, dibenzo-p-dioxin, aromatic degradation, dibenzofuran, dioxin, dioxygenase, ring cleavage

ABSTRACT

Sphingomonas wittichii RW1 is one of a few strains known to grow on the related compounds dibenzofuran (DBF) and dibenzo-p-dioxin (DXN) as the sole source of carbon. Previous work by others (B. Happe, L. D. Eltis, H. Poth, R. Hedderich, and K. N. Timmis, J Bacteriol 175:7313–7320, 1993, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.175.22.7313-7320.1993) showed that purified DbfB had significant ring cleavage activity against the DBF metabolite trihydroxybiphenyl but little activity against the DXN metabolite trihydroxybiphenylether. We took a physiological approach to positively identify ring cleavage enzymes involved in the DBF and DXN pathways. Knockout of dbfB on the RW1 megaplasmid pSWIT02 results in a strain that grows slowly on DBF but normally on DXN, confirming that DbfB is not involved in DXN degradation. Knockout of SWIT3046 on the RW1 chromosome results in a strain that grows normally on DBF but that does not grow on DXN, demonstrating that SWIT3046 is required for DXN degradation. A double-knockout strain does not grow on either DBF or DXN, demonstrating that these are the only ring cleavage enzymes involved in RW1 DBF and DXN degradation. The replacement of dbfB by SWIT3046 results in a strain that grows normally (equal to the wild type) on both DBF and DXN, showing that promoter strength is important for SWIT3046 to take the place of DbfB in DBF degradation. Thus, both dbfB- and SWIT3046-encoded enzymes are involved in DBF degradation, but only the SWIT3046-encoded enzyme is involved in DXN degradation.

IMPORTANCE S. wittichii RW1 has been the subject of numerous investigations, because it is one of only a few strains known to grow on DXN as the sole carbon and energy source. However, while the genome has been sequenced and several DBF pathway enzymes have been purified, there has been very little research using physiological techniques to precisely identify the genes and enzymes involved in the RW1 DBF and DXN catabolic pathways. Using knockout and gene replacement mutagenesis, our work identifies separate upper pathway ring cleavage enzymes involved in the related catabolic pathways for DBF and DXN degradation. The identification of a new enzyme involved in DXN biodegradation explains why the pathway of DBF degradation on the RW1 megaplasmid pSWIT02 is inefficient for DXN degradation. In addition, our work demonstrates that both plasmid- and chromosomally encoded enzymes are necessary for DXN degradation, suggesting that the DXN pathway has only recently evolved.

INTRODUCTION

Sphingomonas wittichii RW1 was isolated from the Elbe River for the ability to degrade dibenzo-p-dioxin (DXN) and dibenzofuran (DBF) (1). The proposed upper catabolic pathway is initiated by an angular dioxygenase, dibenzofuran 4,4a-dioxygenase (2), that catalyzes the conversion of DBF and DXN to 2,2′,3-trihydroxybiphenyl (THB) and 2,2′,3-trihydroxybiphenylether (THBE), respectively. The latter compounds are then cleaved by a meta ring cleavage dioxygenase (3), and a hydrolase (4) converts the meta cleavage products to catechol and salicylate, respectively, which then enter central aromatic metabolic pathways in the cell. The S. wittichii RW1 genome sequence is known (5), and many of the genes involved in the DXN/DBF catabolic pathway have been identified (6, 7) and localized to the RW1 pSWIT02 plasmid. While the RW1 enzymes involved in the DXN and DBF catabolic pathways are thought to be produced constitutively (1), there have been multiple transcriptomic and proteomic studies to identify differentially expressed RW1 genes under different growth conditions (8–12).

Unique to RW1 is the ability to degrade both DXN and DBF. Only a few other bacterial strains are reported to grow on DXN as the sole source of carbon (13, 14). Several bacteria are known to grow on DBF and to cooxidize DXN (15–17). This is a unique conundrum: if the structurally related compounds DXN and DBF are degraded by similar catabolic pathways, then why is it easy to find strains that grow on DBF and so hard to find strains that grow on DXN, and why do strains that grow on DBF fail to grow on DXN? It is prevailing wisdom that the genes for the DBF and DXN upper catabolic pathways are contained on the RW1 pSWIT02 plasmid (5, 7), but pSWIT02-like plasmids are found in other bacteria, and these strains grow on DBF but not DXN (15, 18).

Purification and characterization of the RW1 dibenzofuran 4,4a-dioxygenase (2) indicate that this ring hydroxylating dioxygenase catalyzes the oxidation of DXN at 84% the rate at which it oxidizes DBF. The expression of the RW1 dxnA1A2 oxygenase genes in Escherichia coli, along with the cognate ferredoxin and reductase electron transfer system (6, 7), confirmed that a single enzyme has both DXN and DBF ring hydroxylating activities. Thus, a single dioxygenase enzyme initiates the degradation of both DXN and DBF in RW1, and it is not surprising that other bacteria that grow on DBF can cooxidize DXN. The second enzyme in the RW1 DBF catabolic pathway, 2,2′,3-trihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase (THB 1,2-dioxygenase), has also been extensively studied (3). This meta ring cleavage enzyme is encoded by the dbfB gene located 4.5 kb away from the dxnA1A2BCfdx3 operon on pSWIT02 in RW1 (3, 5). Interestingly, even though DbfB has a Km for 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl and THB in the micromolar range and a Km for catechol and 3-(or 4-)methylcatechol in the millimolar range, the activity against THBE as a substrate is reported to be too low to generate kinetic parameters (3). This means that DbfB would function poorly, if at all, in the DXN catabolic pathway.

Therefore, we hypothesize that the pSWIT02-encoded DbfB meta ring cleavage enzyme functions only in the DBF catabolic pathway and not in the DXN catabolic pathway. We used genomic and transcriptomic guided approaches to identify a second meta ring cleavage enzyme involved in the RW1 upper pathway for DBF and DXN degradation. The role of both DbfB and the newly discovered meta ring cleavage enzyme in DBF and DXN metabolism was verified through gene knockouts and physiological analysis of the resulting mutant strains.

RESULTS

Role of DbfB in DBF and DXN degradation by RW1.

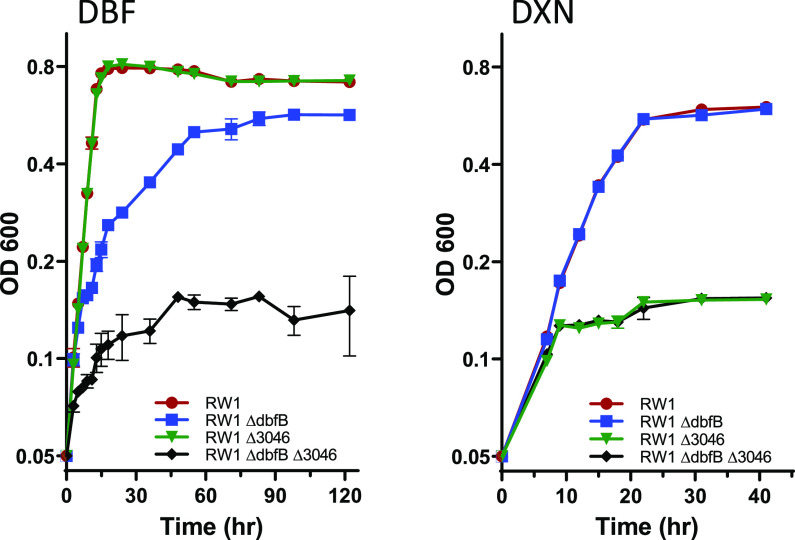

S. wittichii RW1 degrades DBF and DXN through similar pathways. Crucial to these pathways is cleavage of the first aromatic ring. The RW1 upper pathway meta ring cleavage enzyme, encoded by dbfB, has been well studied (3). We were intrigued by the fact that the enzyme has high activity toward the hydroxylated biphenyl compounds 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl and THB (biphenyl and DBF pathway metabolites) but has low activity toward the hydroxylated biphenylether compound THBE (DXN pathway intermediate). The only difference between these two compounds is the oxygen atom joining the two aromatic rings in THBE. As described in Materials and Methods, we knocked out dbfB (SWIT4902), resulting in the RW1ΔdbfB strain. This strain does not grow on DBF and a brown-colored compound identified as THB appears in DBF-containing medium. Thus, the strain is effectively blocked in the upper pathway ring cleavage step. Interestingly, RW1ΔdbfB grows normally on DXN and does not accumulate any noticeable compounds in the culture medium. The inability of RW1ΔdbfB to grow on DBF could be due either to a complete blockage in the catabolic pathway or a partial blockage and the toxic effects of the accumulating THB. Therefore, we analyzed growth of RW1ΔdbfB on both DBF and DXN with Amberlite XAD7HP resin added to adsorb and sequester any THB formed to prevent any toxic effects of this accumulating metabolite. Growth curves of the wild-type RW1 on DXN and DBF with and without the added resin are nearly identical (data not shown). Interestingly, growth curves of RW1ΔdbfB with DBF as the substrate show that deletion of this gene simply slows the growth on DBF (Fig. 1). Interestingly, growth curves of RW1 and RW1ΔdbfB with DXN as the sole carbon source are nearly identical (Fig. 1), showing that the dbfB-encoded upper pathway meta cleavage enzyme is not needed for RW1 to grow on DXN. These data indicate that there must be a second ring cleavage enzyme in RW1 that functions in both the DXN and DBF catabolic pathways.

FIG 1.

Growth of RW1, RW1ΔdbfB, RW1Δ3046, and RW1ΔdbfBΔ3046 on dibenzofuran (DBF; left) and dibenzo-p-dioxin (DXN; right). Data are the averages from triplicates, and the error bars indicate their standard deviations. OD, optical density.

Identification of a second ring cleavage enzyme involved in DXN and DBF degradation by RW1.

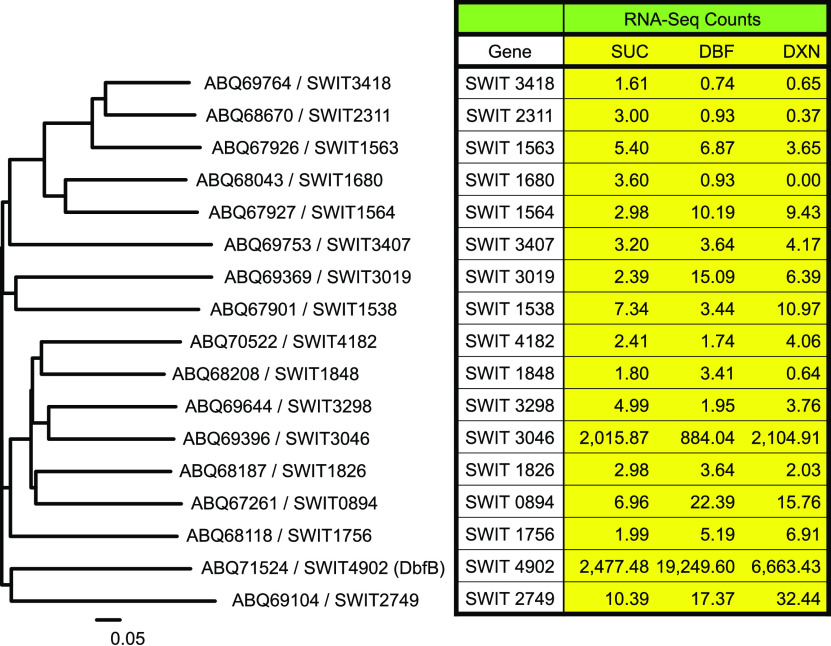

We used a genomic and transcriptomic approach to identify a second ring cleavage enzyme involved in DXN and DBF degradation by RW1. Two transcriptomic and two proteomic studies have been performed on RW1 (8–11). Studies such as these often report gene expression as a ratio between induced and uninduced cultures, but early published work showed that many of the RW1 enzymes involved in DXN and DBF metabolism are constitutively produced (1). By our count, there are 17 potential meta ring cleavage enzymes encoded by the genome of RW1 (Fig. 2) sharing very little homology with each other (the closest two, SWIT2311 and SWIT3418, are only 54.9% identical at the amino acid sequence level). We examined the transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) counts in the Chai et al. transcriptomic study (8) for the genes encoding this diverse array of ring cleavage enzymes following growth of RW1 on succinate, DBF, and DXN. Of the 17 different genes examined, we found that SWIT4902 (dbfB) on the pSWIT02 plasmid and SWIT3046 on the chromosome are expressed at high levels on all three growth substrates (Fig. 2). Thus, we knocked out the SWIT3046 gene as described in Materials and Methods, resulting in strain RW1Δ3046. This knockout strain accumulates THBE from DXN and did not grow on DXN as the sole carbon source even with the resin added to remove THBE from the culture medium (Fig. 1). On the other hand, RW1Δ3046 grew normally on DBF as the sole carbon source (Fig. 1). To confirm and extend these results, the double-knockout strain RW1ΔdbfBΔ3046 was constructed. As expected, this strain did not grow on either DXN or DBF (Fig. 1). These data prove that chromosomally encoded SWIT3046 is absolutely required for RW1 growth on DXN. The data also prove that plasmid-encoded SWIT4902 (DbfB) is the best enzyme for RW1 growth on DBF and that SWIT3046 can partially replace SWIT4902 when the latter gene is knocked out.

FIG 2.

Diversity of RW1 meta ring cleavage enzymes with corresponding RNA-seq counts following growth on different substrates. In the amino acid sequence dendrogram, the ABQ number is the protein ID and the SWIT number is the gene ID in the GenBank database. The gene designation for SWIT4902 is dbfB. The RNA-seq numbers for each gene following growth on succinate (SUC), dibenzofuran (DBF), and dibenzo-p-dioxin (DXN) were extracted from Chai et al. (8) with GEO data set accession number GSE74831 and are the averages from multiple normalized replicates under each growth condition.

Complementation and gene replacement.

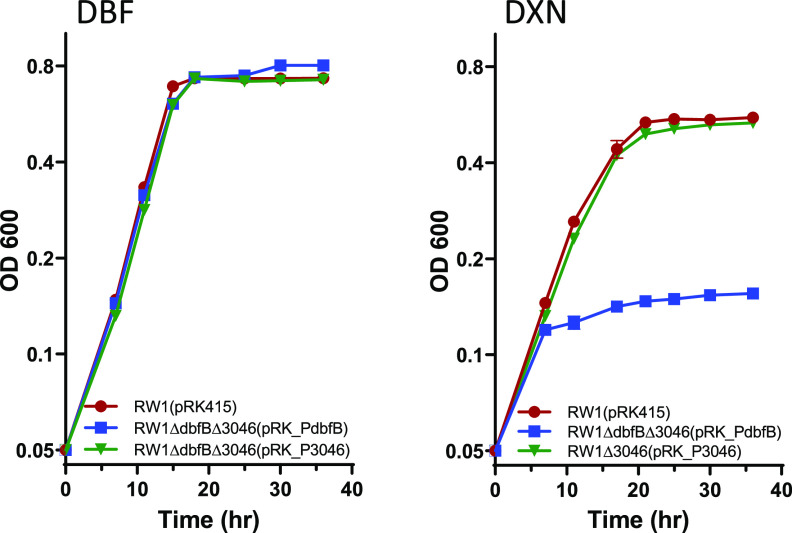

To prove that the growth experiments described above are due to the specific gene knockout and not to a polar effect on downstream genes, complementation experiments were performed. Each of the knockout strains was complemented by the analogous gene (either SWIT4902-dbfB or SWIT3046) cloned into pRK415 under the control of the constitutive dxnA1 promoter normally driving expression of the genes for the initial dioxygenase in both the DXN and DBF pathways. Complementation of each knockout mutant restored wild-type growth (Fig. 3), indicating that the growth phenotypes described above are directly due to loss of either SWIT4902-dbfB or SWIT3046. Interestingly, pRK_P3046 completely restored wild-type growth of the RW1ΔdbfBΔ3046 double knockout on DBF. In the single-knockout RW1ΔdbfB, wild-type SWIT3046 in the chromosome only partially restored growth. We hypothesize that the restoration of wild-type growth by pRK_P3046 is due either to more than one copy of SWIT3046 (pRK415 is a low-copy-number vector with 4 to 6 copies per cell) and/or the expression of SWIT3046 from the constitutive dxn promoter cloned in front of the SWIT3046 gene in pRK415.

FIG 3.

Complementation of the double dbfB and SWIT3046 knockout strain by either cloned dbfB or SWIT3046 on dibenzofuran (DBF; left) and complementation of the SWIT3046 knockout by cloned SWIT3046 on dibenzo-p-dioxin (DXN; right).

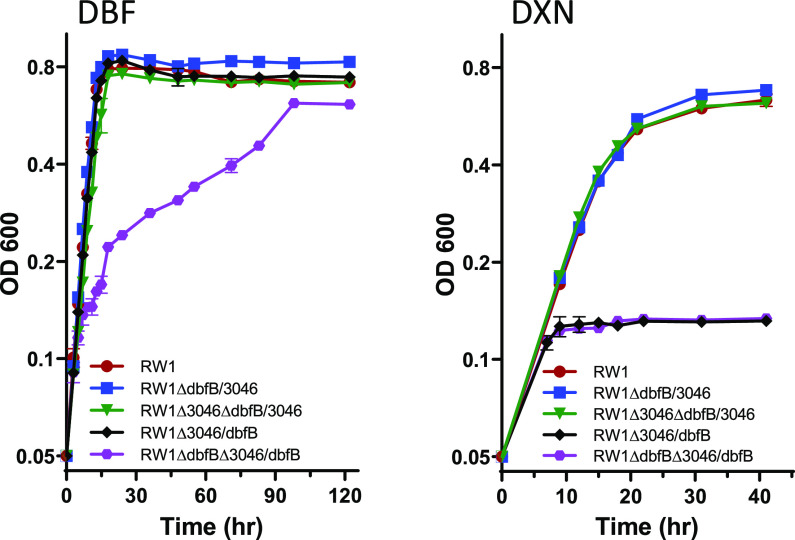

To determine if position in the genome (different promoter) affects the enzymatic activity of SWIT3046, the gene encoding this enzyme was substituted for the dbfB gene. Strain RW1ΔdbfB/3046 has gene SWIT3046 substituted for dbfB and, thus, has two copies of SWIT3046, one in the normal chromosome location and one introduced into the plasmid pSWIT02. Strain RW1Δ3046ΔdbfB/3046 has gene SWIT3046 substituted for dbfB in pSWIT02 and the chromosomally located wild-type SWIT3046 gene knocked out. Thus, this strain has only one copy of SWIT3046, which is relocated from the chromosome to the plasmid pSWIT02 in place of dbfB. The two strains (RW1ΔdbfB/3046 and RW1Δ3046ΔdbfB/3046) grew on DXN and DBF at the same rate and extent as the wild-type strain RW1 (Fig. 4). Thus, these data show that SWIT3046 in its wild-type chromosome location can only partially complement a dbfB knockout mutation but that SWIT3046 in the dbfB location fully complements a dbfB knockout. This is most likely due to the dbfB promoter being stronger than the SWIT3046 promoter and is also borne out by the RNA-seq data (8), where raw counts of dbfB are 3.2 times higher during growth on DXN and 21.8 times higher during growth on DBF compared to SWIT3046 (Fig. 2).

FIG 4.

Growth of gene replacement constructs on dibenzofuran (DBF; left) and dibenzo-p-dioxin (DXN; right). Data are averages from triplicates, and the error bars indicate their standard deviations.

To extend and confirm these results, the reverse experiment of replacing SWIT3046 with dbfB was performed. Strain RW1Δ3046/dbfB has gene dbfB substituted for SWIT3046 and, thus, has two copies of dbfB, one copy in the normal location in pSWIT02 and one copy introduced into the chromosome in place of SWIT3046. Strain RW1ΔdbfBΔ3046/dbfB has gene dbfB substituted for SWIT3046, wild-type dbfB is knocked out, and, thus, the strain has only one copy of dbfB (moved from pSWIT02 to the chromosome in place of SWIT3046). As expected, neither strain grew on DXN (Fig. 4), confirming the importance of SWIT3046 in DXN degradation. Two copies of dbfB did not increase growth on DBF compared to the wild-type RW1 (Fig. 4), indicating that other factors control the maximal rate of growth on this substrate. However, a single copy of dbfB in the chromosome, linked to the SWIT3046 promoter, grew slower than the wild-type strain on DBF, again demonstrating that the SWIT3046 promoter is not as strong as the dbfB promoter (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data demonstrate that both enzyme specificity and quantity of the enzyme produced (promoter strength) govern the rate and ability of RW1 to grow on either DXN or DBF.

DISCUSSION

S. wittichii RW1 is one of only a very few organisms known to grow on DXN as the sole source of carbon and energy (19, 20). Due to the environmental importance of DXN degradation, RW1 has been the subject of intense studies, ranging from genetics (5, 7–9, 12, 21–23) and biochemistry (2–4, 6, 24–27) to field applications (28–36). Two important questions remain to be answered: exactly which enzymes are involved in the DXN and DBF catabolic pathways, and how did this organism evolve? The RW1 DXN and DBF catabolic pathway enzymes have been purified and characterized; genes have been cloned and heterologously expressed; and transcriptomic, proteomic, and transposon sequencing (Tn-Seq) information has been generated. To our knowledge, knockout mutagenesis and physiological characterization have not been used previously to identify genes and enzymes involved in RW1 catabolic pathways.

It has been known for more than 25 years that the RW1 upper pathway ring cleavage enzyme DbfB has strong activity toward the DBF metabolite THB and weak activity toward the DXN metabolite THBE (3). The work presented here confirms that conclusion, since the knockout of dbfB results in a strain that grows weakly on DBF but normally on DXN. Using a genomic and transcriptomic guided approach, we identified a second ring cleavage enzyme, SWIT3046, which is absolutely required for RW1 growth on DXN. SWIT3046 can partially replace DbfB, explaining why dbfB knockouts still grow on DBF. The involvement of SWIT3046 and dbfB in DBF and DXN metabolism is summarized by the metabolic map in Fig. 5. It is important to note that understanding the role of gene expression levels is crucial in determining the role of enzymes in catabolic pathways. Positioning SWIT3046 downstream of a stronger promoter increased the ability of the enzyme to complement a dbfB knockout mutation, increasing the level of complementation from partial to full, as exhibited by DBF growth curves of the various RW1 constructs. If SWIT3046 was not constitutively expressed, then the ability to partially replace dbfB would not have been naturally detected. Thus, in wild-type strains, not only the enzyme characteristics (i.e., Vmax and Km for a particular substrate) but also the levels of gene expression are important in determining whether or not an enzyme is involved in a particular catabolic pathway. It is important to note that the different clusters of genes for DBF and DXN degradation are constitutively expressed, and, in some cases, the constitutive expression is higher in the presence of DBF or DXN. This is evidenced by whole-cell enzyme assays performed more than 25 years ago and by more recent raw data from RNA-seq experiments. The constitutive nature of DBF and DXN metabolism in RW1 and the recruitment of a chromosomal gene for the second step of the DXN pathway highly suggest that the ability to degrade one or both of these substrates has recently evolved. Our experiments strongly point in this direction, because when pSWIT02 dbfB was replaced with the chromosome SWIT3046 gene, the new strain could grow on both DXN and DBF. A more highly evolved organism would already have SWIT3046 moved to the pSWIT02 plasmid so that the genes could conjugate as a unit into a different bacterium and bring an essential gene for DXN degradation with it. Interestingly, SWIT3046 and DbfB are quite different from each other (Fig. 2), with a one-to-one alignment showing only 31% identity and 48% similarity.

FIG 5.

Metabolic map showing the role of DbfB and SWIT3046 in dibenzofuran and dibenzo-p-dioxin degradation by S. wittichii RW1. The redA2, fdx3, dxnA1, and dxnA2 genes code for the reductase, ferredoxin, and oxygenase alpha and beta subunits of the initial dioxygenase; dbfB codes for the THB ring cleavage dioxygenase; dxnB codes for a hydrolase; dxnC codes for a TonB-dependent receptor; and SWIT3048 to SWIT3043 encode (in order) a TonB-dependent receptor, a phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase, a THB/THBE ring cleavage dioxygenase, an FAD-containing monooxygenase, a second TonB-dependent receptor, and a sulfatase.

The natural substrate for SWIT3046 remains undetermined. Based on the genome sequence (GenBank accession number CP000699.1), SWIT3046 is in a potential operon with open reading frames annotated (in order, genes SWIT3048 to SWIT3043; Fig. 5) as a TonB-dependent receptor, a phytanoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) dioxygenase, SWIT3046, an FAD-containing monooxygenase, a second TonB-dependent receptor, and a sulfatase. The operon is preceded by a transposon, and some transposons are known for activating adjacent genes by readthrough of a promoter. Upstream and oriented in the opposite direction is an operon potentially encoding a dioxygenase and a gentisate pathway, and it contains the dxnB2 gene, encoding a well-studied hydrolase (37). It is possible that the natural substrate of SWIT3046 is the enzymatic product of the adjacently encoded monooxygenase. The identity of the natural substrate remains unknown.

Our work explains why DXN-degrading bacteria are rarely found in nature, unlike DBF-degrading bacteria. The RW1 enzymes for DBF degradation are encoded by the potentially transmissible plasmid pSWIT02, which is found in other DBF (but not DXN)-degrading organisms (Sphingomonas sp. strain HH69 contains pSWIT02 [15], for instance). It is highly likely that pSWIT02 evolved as a transmissible plasmid for the degradation of dibenzofuran. This is evidenced by its presence in a variety of dibenzofuran degraders and the high homology of the encoded enzymes to dibenzofuran-degrading enzymes in other bacteria. However, these dibenzofuran pathways have a blockage point for dibenzo-p-dioxin degradation at the ring cleavage step. To evolve a pathway for dibenzo-p-dioxin degradation, either the pSWIT02-encoded enzymes must evolve or a host with suitable enzymes must be found. In the case of S. wittichii RW1, the second route was taken, and a host with a suitable THBE cleavage enzyme was utilized. S. wittichii was chosen because a simple BLASTP search with SWIT3046 shows that this enzyme is found only in S. wittichii strains (above 97% identity, while the next best matches are below 60% identity). Once pSWIT02 is in a host like RW1 with an appropriate SWIT3046-like ring cleavage enzyme, a DXN-degrading strain is formed. Thus, both plasmid- and chromosome-encoded enzymes are needed for RW1 to degrade DXN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

Sphingomonas wittichii RW1 is the wild-type strain capable of utilizing dibenzofuran and dibenzo-p-dioxin as the sole carbon and energy source (1). E. coli DH5α was the recipient strain in all cloning experiments. The pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to clone PCR products. pRK415 (38) was used to construct clones for gene knockout and for complementation experiments. Mineral salts basal (MSB) medium (39) was used for carbon source and metabolite accumulation studies. When needed, l-phenylalanine was added to MSB at 10 mM final concentration. DBF and DXN were dissolved in acetone in a sterile flask to a calculated final concentration of 3 mM, and the flasks were left in a fume hood for 5 to 6 h to allow for complete evaporation of the acetone. After addition of MSB medium, the flasks were sonicated in a Branson 1800 water bath sonicator for 5 min to disperse the substrate crystals throughout the medium. DBF and DXN crystals were added on the lid of the MSB agar petri dish for growth tests as the sole carbon source. Amberlite XAD7HP resin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added at 2 mg/ml MSB broth when needed. LB agar and LB broth were used as complete media. The RW1 wild type and all mutants were grown aerobically at 30°C, and E. coli strains were aerobically cultured in LB medium at 37°C. Ampicillin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and tetracycline were added to the medium, when needed, at 100, 15, 50, and 15 μg/ml, respectively.

All strains and plasmid constructs are listed in Table 1, and all PCR primer sequences used to make the plasmid constructs are in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

List of strains and plasmids

| Strain/plasmid | Description | Reference and/or source |

|---|---|---|

| RW1 | Sphingomonas wittichii RW1 wild-type strain | 1; obtained from DSMZ |

| RW1ΔdbfB | RW1 with a kanamycin resistance cassette inserted into dbfB | This study |

| RW1Δ3046 | RW1 with a gentamycin resistance cassette inserted into SWIT3046 | This study |

| RW1ΔdbfBΔ3046 | RW1 with a kanamycin resistance cassette inserted into dbfB and a gentamycin resistance cassette inserted into SWIT3046 | This study |

| RW1ΔdbfB/3046 | RW1 with SWIT3046 substituted for dbfB; gene substitution begins at the start codon; this strain has two copies of SWIT3046 and no dbfB | This study |

| RW1Δ3046ΔdbfB/3046 | RW1Δ3046 with SWIT3046 substituted for dbfB; gene substitution begins at the start codon; this strain has one copy of SWIT3046 in the dbfB location | This study |

| RW1Δ3046/dbfB | RW1 with dbfB substituted for SWIT3046; gene substitution begins at the start codon; this strain has two copies of dbfB and no SWIT3046 | This study |

| RW1ΔdbfBΔ3046/dbfB | RW1ΔdbfB with dbfB substituted for SWIT3046; gene substitution begins at the start codon; this strain has one copy of dbfB in the SWIT3046 location | This study |

| pRK_PdbfB | pRK415 with the dxnA1 promoter region in front of dbfB | This study |

| pRK_P3046 | pRK415 with the dxnA1 promoter region in front of SWIT3046 | This study |

| pRK_dbfBKO | pRK415 containing dbfB with flanking regions | This study |

| pRK_dbfBKO-km | pRK_dbfBKO with a kanamycin resistance cassette cloned into dbfB for constructing the dbfB knockout mutation | This study |

| pRK_3046KO | pRK415 containing SWIT3046 with flanking regions | This study |

| pRK_3046KO-gm | pRK_3046KO with a gentamycin resistance cassette cloned into SWIT3046 for constructing the SWIT3046 knockout mutation | This study |

| pGEMT_fB3046 | pGEM-T with gene SWIT3046 with dbfB flanking regions | This study |

| pRK_fB3046 | pRK415 with gene SWIT3046 with dbfB flanking regions | This study |

| pRK_fB3046-km | pRK_fB3046 with a kanamycin resistance cassette after SWIT3046 for constructing the dbfB to SWIT3046 replacement strains | This study |

| pGEMT_f3046B | pGEM-T containing gene dbfB with SWIT3046 flanking regions | This study |

| pRK_f3046B | pRK415 containing gene dbfB with SWIT3046 flanking regions | This study |

| pRK_f3046B-km | pRK_f3046B with a kanamycin resistance cassette after dbfB for constructing the SWIT3046 to dbfB replacement strains | This study |

| pRK415 | Unstable broad host range cloning vector | 38 |

| pRK2013 | Helper plasmid for conjugation experiments | 43 |

| p34S-Km3 | Source of the kanamycin resistance cassette | 41, 44 |

| p34S-Gm | Source of the gentamycin resistance cassette | 41 |

TABLE 2.

List of PCR primers

| Construct | PCR primer | PCR product |

|---|---|---|

| pRK_dbfBKO | GGGGAATTCGAATCCTTCGCTGCACACAGGGC | dbfB with flanking regions |

| CCAAGCTTGCGGGATACCTCATTCGTCGTCG | ||

| pRK_dbfBKO-km | CCCCTCGAGCGAGCTCAAAGCCACGTTGTGTCTC | Kanamycin resistance gene |

| CCCTCGAGCGGGTACCGAGCTCTTAGAAAAACTC | ||

| pRK_3046KO | GGAAGCTTCAGATGGGGAGCAACAACATGGC | SWIT3046 with flanking regions |

| GGTCTAGAGTGCGTCGACCAGGAGTAGATG | ||

| pRK_PdbfB | GGGAAGCTTGCCTGTCTCCGAGATGTCTG | dxnA1 promoter region with dbfB overlap |

| CTCCAAACCCTGCAGGCAACCTCTCCTGCAT | ||

| pRK_PdbfB | GCCTGCAGGGTTTGGAGCAAAAGGAGAGT | dbfB with dxnA1 promoter region overlap |

| TCTAGAGGTGTATGGCCTTAATAATTCAATGCGC | ||

| pRK_PdbfB | GGGAAGCTTGCCTGTCTCCGAGATGTCTG | dxnA1 promoter and dbfB combined |

| TCTAGAGGTGTATGGCCTTAATAATTCAATGCGC | ||

| pRK_P3046 | CTGCAGGCCTGTCTCCGAGATGTCT | dxnA1 promoter region |

| AAGCTTGCAACCTCTCCTGCATCCT | ||

| pRK_P3046 | GGAAGCTTCGCGTGGCGTTTCGATCCATG | SWIT3046 |

| GGTCTAGAGCAGGCTTCCGACCCGGTG | ||

| pRK_fB3046 | GGAAGCTTCGTTAGCCTCTCACGAGTG | dbfB upstream region with short SWIT3046 overlap |

| GATTTCAGACATGACGATAACTCTCCTTTTGC | ||

| pRK_fB3046 | GAGTTATCGTCATGTCTGAAATCTCGAGCC | SWIT3046 with short dbfB upstream and downstream overlap |

| GTGTATGGCCTCTAGAGTCAATGCGCGTGCGCGTGTC | ||

| pRK_fB3046 | CGCGCATTGACTCTAGAGGCCATACACCTAACATTGTC | dbfB downstream region with short SWIT3046 overlap |

| CGGATCCCCACCTCAAGCGCATCCTG | ||

| pRK_fB3046 | GGAAGCTTCGTTAGCCTCTCACGAGTG | dbfB upstream flank- SWIT3046-dbfB downstream flank |

| CCGGATCCCCACCTCAAGCGCATCCTG | ||

| pRK_f3046B | GGAAGCTTACCGGCTTCCGGGCTACACGCTGCT | SWIT3046 upstream region with short dbfB overlap |

| TTACTGACATCGGAACACCTCATGATCAGGATCGTC | ||

| pRK_f3046B | GAGGTGTTCCGATGTCAGTAAAACAACTTGGC | dbfB with short SWIT3046 upstream and downstream overlap |

| CGCGGGATCCTCAATGCGCCGGCAACTG | ||

| pRK_f3046B | GGCGCATTGAGGATCCCGCGGCCACCGGGTCGGAAG | SWIT3046 downstream region with short dbfB overlap |

| CCGGTACCGAGCAGCTCCGCGCCGGCCT | ||

| pRK_f3046B | GGAAGCTTACCGGCTTCCGGGCTACACGCTGCT | SWIT3046 upstream flank-dbfB-SWIT3046 downstream flank |

| CCGGTACCGAGCAGCTCCGCGCCGGCCT |

DNA techniques.

Total genomic DNA from RW1 and RW1-derived strains was prepared using the Qiagen (Germantown, MD) Ultra Clean microbial kit, and plasmid DNA was purified using the Macherey-Nagel (Bethlehem, PA) NucleoSpin plasmid kit by following the manufacturers’ instructions. Transformation of plasmid DNA into competent E. coli strains was performed by the calcium chloride-glycerol transformation procedure (40). PCR products and restriction fragments were purified using the GeneClean III kit (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Restriction enzymes and ligations of DNA samples were performed as recommended by the supplier (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). All PCR amplifications were performed with the NEB Phusion high-fidelity kit when the genes were needed for downstream applications and with NEB Taq when used for mapping and screening purposes following instructions from the supplier. All PCR-generated fragments used for downstream applications were sequenced to verify that no base changes were introduced. DNA sequencing was conducted by Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ).

Construction of ring cleavage dioxygenase knockout mutants and complementation clones.

Gene inactivation was achieved by disrupting the gene with an antibiotic cassette and was introduced into the chromosome by homologous recombination. The dbfB gene was amplified by PCR using RW1 chromosomal DNA with flanking regions 0.59 kb upstream of the gene start codon and 0.5 kb downstream of the gene stop codon using the primers GGGGAATTCGAATCCTTCGCTGCACACAGGGC and CCAAGCTTGCGGGATACCTCATTCGTCGTCG, containing EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites, respectively. The resulting 1.98-kb DNA fragment was gel purified, digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and ligated into similarly digested pRK415 to form pRK_dbfBKO and then was disrupted with a kanamycin resistance cassette that was PCR amplified using p34S-Km3 plasmid as a template (41) with the primers CCCCTCGAGCGAGCTCAAAGCCACGTTGTGTCTC and CCCTCGAGCGGGTACCGAGCTCTTAGAAAAACTC, containing an XhoI restriction site for both ends, digested with XhoI, and ligated into similarly digested pRK_dbfBKO to form pRK_dbfBKO-km. The final construct was transformed into DH5α and sequenced.

SWIT3046 was amplified by PCR with a flanking region 0.9 kb upstream of the gene start codon and 0.35 kb downstream of the gene stop codon with the primers GGAAGCTTCAGATGGGGAGCAACAACATGGC and GGTCTAGAGTGCGTCGACCAGGAGTAGATG, containing HindIII and XbaI restriction sites, respectively. The resulting 2.1-kb DNA fragment was purified and digested with HindIII and XbaI and ligated into similarly digested pRK415 to form pRK_3046KO. A gentamicin resistance cassette was used to disrupt SWIT3046 in the unique XhoI site after digestion of p34S-Gm (41) with SalI and ligated into XhoI-digested pRK_3046KO (SalI and XhoI have compatible ends). The resulting construct pRK_3046KO-gm was transformed into DH5α and sequenced.

RW1 knockout mutants were constructed as previously described by us for Sphingobium yanoikuyae B1 (42). The two constructs, pRK_dbfBKO-km and pRK_3046KO-gm, were individually transferred into RW1 by triparental mating using the helper E. coli pRK2013 (43) with selection on MSB supplemented with phenylalanine and tetracycline. The transconjugants were cultured in 5 ml LB broth and transferred into a new volume of 5 ml LB broth every day allowing for the double recombination event to occur. To screen for recombination, colonies were tested for kanamycin (dbfB knockout) or gentamicin (SWIT3046 knockout) resistance and tetracycline sensitivity on LB agar. The presence or absence of the plasmid constructs and the occurrence of the desired double recombination event were verified by PCR using the above-mentioned primers for each construct.

Complementation of the mutants was performed by cloning dbfB and SWIT3046 into pRK415 downstream of the constitutive dxnA1 promoter. For dbfB, a 0.44-kb fragment of the dxnA1 promoter region was PCR amplified using primer GGGAAGCTTGCCTGTCTCCGAGATGTCTG (containing a HindIII site, underlined) and primer CTCCAAACCCTGCAGGCAACCTCTCCTGCAT (containing a PstI site and an overlap sequence with the dbfB upstream fragment primer). A 0.94-kb region of dbfB was PCR amplified using the primers GCCTGCAGGGTTTGGAGCAAAAGGAGAGT (containing a PstI site and an overlap sequence with the dxn promoter downstream fragment primer) and TCTAGAGGTGTATGGCCTTAATAATTCAATGCGC (containing an XbaI site). The two fragments were purified and ligated by PCR overlap extension using the following protocol. The two PCR fragments were mixed in one PCR at a 1:1 ratio using the Phusion HF PCR kit, without adding any primer, under the following conditions: denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 72°C for 40 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min for 10 cycles. Next, primer GGGAAGCTTGCCTGTCTCCGAGATGTCTG and primer TCTAGAGGTGTATGGCCTTAATAATTCAATGCGC were added, and the reaction mixture was returned to the PCR machine for another 25 cycles under the same conditions. The resulting 1.38-kb fragment was purified from an agarose gel, digested with HindIII and XbaI, and cloned into similarly digested pRK415 to yield pRK_PdbfB, transformed into DH5α, and sequenced to verify.

For the second expression clone, a 0.97-kb fragment containing SWIT3046 was PCR amplified using primer GGAAGCTTCGCGTGGCGTTTCGATCCATG (containing a HindIII site) and primer GGTCTAGAGCAGGCTTCCGACCCGGTG (containing an XbaI site). The resulting fragment was purified from an agarose gel, cloned into pGEM-T to yield pGEMT_3046, and sequenced to verify. The dxnA1 promoter was PCR amplified using primers CTGCAGGCCTGTCTCCGAGATGTCT (containing a PstI site) and AAGCTTGCAACCTCTCCTGCATCCT (containing a HindIII site). The resulting 0.44-kb fragment was purified from an agarose gel and digested with PstI and HindIII. pGEMT_3046 was digested with HindIII and XbaI and purified from an agarose gel. The two purified fragments, of 0.44 kb and 0.97 kb, were cloned into pRK415 digested with PstI and XbaI by a three-way ligation to yield pRK_P3046.

The final constructs, pRK_PdbfB and pRK_P3046, were transformed into DH5α and transferred into the appropriate mutant strain by triparental mating with selection on MSB with phenylalanine and tetracycline. The presence of the constructs in the RW1 mutant strains was verified by PCR.

Gene replacement constructs.

RW1ΔdbfB grows slowly on DBF; thus, gene replacement was carried out to determine if this was caused by a promoter problem by swapping SWIT3046 from the chromosome into pSWIT02 in place of dbfB and swapping dbfB from pSWIT02 into the chromosome in place of SWIT3046. A 1.05-kb region upstream of the dbfB start codon, including the dbfB ribosomal binding site, was amplified by PCR using the primers GGAAGCTTCGTTAGCCTCTCACGAGTG (containing a HindIII restriction site) and GATTTCAGACATGACGATAACTCTCCTTTTGC (containing overlap sequence with SWIT3046). SWIT3046 was PCR amplified from the start codon without its ribosomal binding site using the primers GAGTTATCGTCATGTCTGAAATCTCGAGCC (containing overlap sequence with the dbfB upstream fragment primer) and GTGTATGGCCTCTAGAGTCAATGCGCGTGCGCGTGTC (containing overlap sequence with the dbfB downstream fragment and an XbaI restriction site for adding the antibiotic cassette). A 1.05-kb region downstream of dbfB was PCR amplified using the primers CGCGCATTGACTCTAGAGGCCATACACCTAACATTGTC (containing overlap sequence with the primer for the end of SWIT3046 and the XbaI restriction site) and CCGGATCCCCACCTCAAGCGCATCCTG (containing a BamHI restriction site). All three fragments were ligated by PCR overlap extension using the following protocol. The three PCR fragments were purified and mixed in one PCR at a 1:1:1 ratio using the Phusion HF PCR kit without adding any primer under the following conditions: denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 72°C for 40 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min for 10 cycles. Next, the primers GGAAGCTTCGTTAGCCTCTCACGAGTG (the forward primer from upstream fragment-HindIII) and CCGGATCCCCACCTCAAGCGCATCCTG (the reverse primer for downstream fragment-BamHI) were added, and the reaction mixture was returned to the PCR machine for another 25 cycles under the same conditions. The resulting 3-kb fragment was purified from an agarose gel and cloned into pGEM-T to yield pGEMT_fB3046, transformed into DH5α, and sequenced. pGEMT_fB3046 was digested with HindIII and BamHI and ligated into the similarly digested pRK415 to make pRK_fB3046. A kanamycin antibiotic cassette was digested from p34S-Km3 with XbaI and ligated into similarly digested pRK_fB3046. The final construct, pRK_fB3046-km, was transferred into RW1 and RWΔ3046 for double reciprocal recombination as described above to obtain RW1ΔdbfB/3046 (dbfB replaced by SWIT3046 equals two copies of SWIT3046) and RW1Δ3046ΔdbfB/3046 (SWIT3046 knockout with dbfB replaced by SWIT3046 equals one copy of SWIT3046).

Using a similar approach, SWIT3046 was replaced by dbfB. A 1.1-kb upstream region just before the start codon of SWIT3046 and including the ribosome binding site was PCR amplified using the primers GGAAGCTTACCGGCTTCCGGGCTACACGCTGCT (containing a HindIII site) and TTACTGACATCGGAACACCTCATGATCAGGATCGTC (containing overlap sequence with the beginning of dbfB). A 0.88-kb region of dbfB was amplified, starting from the start codon without its ribosome binding site using the primers GAGGTGTTCCGATGTCAGTAAAACAACTTGGC (containing overlap sequence with the end of the upstream fragment) and CGCGGGATCCTCAATGCGCCGGCAACTG (containing a BamHI site). A 1.1-kb downstream region of SWIT3046 was PCR amplified using the primers GGCGCATTGAGGATCCCGCGGCCACCGGGTCGGAAG (containing an overlap sequence with the end of dbfB and a BamHI site for adding an antibiotic cassette) and CCGGTACCGAGCAGCTCCGCGCCGGCCT (containing a KpnI site). The three fragments were ligated by PCR overlap extension using the same conditions mentioned above, and after 10 cycles the primers GGAAGCTTACCGGCTTCCGGGCTACACGCTGCT (forward of upstream fragment with HindIII) and CCGGTACCGAGCAGCTCCGCGCCGGCCT (reverse of downstream fragment with KpnI), the reaction mixture was returned to the PCR machine for another 25 cycles. The resulting 3-kb DNA fragment was gel purified and cloned into pGEM-T to make pGEMT_f3046B, transformed into DH5α, and sequenced. The 3-kb HindIII and KpnI fragment was removed from pGEMT_f3046B and ligated into similarly digested pRK415 to make pRK_f3046B. A kanamycin cassette from p34S-Km3 was digested with BamHI and ligated into similarly digested pRK_f3046B. The final construct, pRK_f3046B-km, was transferred by triparental mating, using pRK2013, into RW1 and RW1ΔdbfB for double reciprocal recombination, as described above, to obtain the strains RW1Δ3046/dbfB (SWIT3046 replaced by dbfB equals two copies of dbfB) and RW1ΔdbfBΔ3046/dbfB (dbfB knockout with SWIT3046 replaced by dbfB equals one copy of dbfB).

Growth curves.

RW1 and RW1 constructs were incubated overnight on LB agar with the appropriate antibiotic at 30°C. LB broth (50 ml) was inoculated with a loopful of cells and incubated overnight at 30°C in a rotary shaker (180 rpm). MSB broth (50 ml) with phenylalanine was inoculated from the LB broth culture with a starting optical density at 600 nm of 0.05 and incubated at 30°C in a rotary shaker (180 rpm). The strains were grown in MSB-phenylalanine twice, and when the optical density (600 nm) of the cells reached 2.0 in the second culture, triplicate MSB broth cultures containing either 3 mM DBF or 3 mM DXN were inoculated from each strain and optical density (600 nm) readings taken at specific times. All growth curves were plotted using Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Chemicals and HPLC analysis.

DBF and DXN were obtained from TCI Chemicals (Portland, OR). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was conducted with a Beckman HPLC system (Brea, CA) using an acidic (1% acetic acid) methanol gradient (0% to 100%), a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and a C18 column (4.6 mm by 25 mm). Under these conditions, THB and THBE had retention times of 31 and 30.2 min, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T.Y.M. gratefully acknowledges the support of the Higher Committee for Education Development (HCED) in Iraq for fellowship support. G.J.Z. acknowledges support from NIEHS grant P42-ES004911 under the Superfund Research Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wittich RM, Wilkes H, Sinnwell V, Francke W, Fortnagel P. 1992. Metabolism of dibenzo-p-dioxin by Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Appl Environ Microbiol 58:1005–1010. 10.1128/AEM.58.3.1005-1010.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunz PV, Cook AM. 1993. Dibenzofuran 4,4a-dioxygenase from Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1: angular dioxygenation by a three-component enzyme system. J Bacteriol 175:6467–6475. 10.1128/jb.175.20.6467-6475.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Happe B, Eltis LD, Poth H, Hedderich R, Timmis KN. 1993. Characterization of 2,2',3-trihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase, an extradiol dioxygenase from the dibenzofuran- and dibenzo-p-dioxin-degrading bacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. J Bacteriol 175:7313–7320. 10.1128/jb.175.22.7313-7320.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bünz PV, Falchetto R, Cook AM. 1993. Purification of two isofunctional hydrolases (EC 3.7.1.8) in the degradative pathway for dibenzofuran in Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Biodegradation 4:171–178. 10.1007/BF00695119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller TR, Delcher AL, Salzberg SL, Saunders E, Detter JC, Halden RU. 2010. Genome sequence of the dioxin-mineralizing bacterium Sphingomonas wittichii RW1. J Bacteriol 192:6101–6102. 10.1128/JB.01030-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armengaud J, Gaillard J, Timmis KN. 2000. A second [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin from Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 can function as an electron donor for the dioxin dioxygenase. J Bacteriol 182:2238–2244. 10.1128/jb.182.8.2238-2244.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armengaud J, Happe B, Timmis KN. 1998. Genetic analysis of dioxin dioxygenase of Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1: catabolic genes dispersed on the genome. J Bacteriol 180:3954–3966. 10.1128/JB.180.15.3954-3966.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chai B, Tsoi TV, Iwai S, Liu C, Fish JA, Gu C, Johnson TA, Zylstra G, Teppen BJ, Li H, Hashsham SA, Boyd SA, Cole JR, Tiedje JM. 2016. Sphingomonas wittichii strain RW1 genome-wide gene expression shifts in response to dioxins and clay. PLoS One 11:e0157008. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coronado E, Roggo C, Johnson DR, van der Meer JR. 2012. Genome-wide analysis of salicylate and dibenzofuran metabolism in Sphingomonas wittichii RW1. Front Microbiol 3:300. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartmann EM, Armengaud J. 2014. Shotgun proteomics suggests involvement of additional enzymes in dioxin degradation by Sphingomonas wittichii RW1. Environ Microbiol 16:162–176. 10.1111/1462-2920.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colquhoun DR, Hartmann EM, Halden RU. 2012. Proteomic profiling of the dioxin-degrading bacterium Sphingomonas wittichii RW1. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012:408690. 10.1155/2012/408690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai B, Tsoi T, Sallach JB, Liu C, Landgraf J, Bezdek M, Zylstra G, Li H, Johnston CT, Teppen BJ, Cole JR, Boyd SA, Tiedje JM. 2019. Bioavailability of clay-adsorbed dioxin to Sphingomonas wittichii RW1 and its associated genome-wide shifts in gene expression. Sci Total Environ 712:135525. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong HB, Nam IH, Murugesan K, Kim YM, Chang YS. 2004. Biodegradation of dibenzo-p-dioxin, dibenzofuran, and chlorodibenzo-p-dioxins by Pseudomonas veronii PH-03. Biodegradation 15:303–313. 10.1023/b:biod.0000042185.04905.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura N, Urushigawa Y. 2001. Metabolism of dibenzo-p-dioxin and chlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin by a gram-positive bacterium, Rhodococcus opacus SAO101. J Biosci Bioeng 92:138–143. 10.1263/jbb.92.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harms H, Wittich RM, Sinnwell V, Meyer H, Fortnagel P, Francke W. 1990. Transformation of dibenzo-p-dioxin by Pseudomonas sp. strain HH69. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:1157–1159. 10.1128/AEM.56.4.1157-1159.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasuga K, Habe H, Chung JS, Yoshida T, Nojiri H, Yamane H, Omori T. 2001. Isolation and characterization of the genes encoding a novel oxygenase component of angular dioxygenase from the gram-positive dibenzofuran-degrader Terrabacter sp strain DBF63. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 283:195–204. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubota M, Kawahara K, Sekiya K, Uchida T, Hattori Y, Futamata H, Hiraishi A. 2005. Nocardioides aromaticivorans sp. nov., a dibenzofuran-degrading bacterium isolated from dioxin-polluted environments. Syst Appl Microbiol 28:165–174. 10.1016/j.syapm.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolz A. 2014. Degradative plasmids from sphingomonads. FEMS Microbiol Lett 350:9–19. 10.1111/1574-6968.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiraishi A. 2003. Biodiversity of dioxin-degrading microorganisms and potential utilization in bioremediation. Microb Environ 18:105–125. 10.1264/jsme2.18.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saibu S, Adebusoye SA, Oyetibo GO. 11 February 2020. Aerobic bacterial transformation and biodegradation of dioxins: a review. Bioresour Bioprocess 10.1186/s40643-020-0294-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armengaud J, Timmis KN, Wittich RM. 1999. A functional 4-hydroxysalicylate/hydroxyquinol degradative pathway gene cluster is linked to the initial dibenzo-p-dioxin pathway genes in Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. J Bacteriol 181:3452–3461. 10.1128/JB.181.11.3452-3461.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roggo C, Coronado E, Moreno-Forero SK, Harshman K, Weber J, van der Meer JR. 2013. Genome-wide transposon insertion scanning of environmental survival functions in the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degrading bacterium Sphingomonas wittichii RW1. Environ Microbiol 15:2681–2695. 10.1111/1462-2920.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bunz PV, Buck M, Hebenbrock S, Fortnagel P. 1999. Stability of mutations in a Sphingomonas strain. Can J Microbiol 45:404–407. 10.1139/w99-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armengaud J, Timmis KN. 1997. Molecular characterization of Fdx1, a putidaredoxin-type [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin able to transfer electrons to the dioxin dioxygenase of Sphingomonas sp. RW1. Eur J Biochem 247:833–842. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armengaud J, Timmis KN. 1998. The reductase RedA2 of the multi-component dioxin dioxygenase system of Sphingomonas sp. RW1 is related to class-I cytochrome P450-type reductases. Eur J Biochem 253:437–444. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2530437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seah SY, Ke J, Denis G, Horsman GP, Fortin PD, Whiting CJ, Eltis LD. 2007. Characterization of a C-C bond hydrolase from Sphingomonas wittichii RW1 with novel specificities towards polychlorinated biphenyl metabolites. J Bacteriol 189:4038–4045. 10.1128/JB.01950-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortin PD, Lo AT, Haro MA, Kaschabek SR, Reineke W, Eltis LD. 2005. Evolutionarily divergent extradiol dioxygenases possess higher specificities for polychlorinated biphenyl metabolites. J Bacteriol 187:415–421. 10.1128/JB.187.2.415-421.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halden RU, Halden BG, Dwyer DF. 1999. Removal of dibenzofuran, dibenzo-p-dioxin, and 2-chlorodibenzo-p-dioxin from soils inoculated with Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:2246–2249. 10.1128/AEM.65.5.2246-2249.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong HB, Chang YS, Nam IH, Fortnagel P, Schmidt S. 2002. Biotransformation of 2,7-dichloro- and 1,2,3,4-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin by Sphingomonas wittichii RW1. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:2584–2588. 10.1128/aem.68.5.2584-2588.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nam IH, Hong HB, Kim YM, Kim BH, Murugesan K, Chang YS. 2005. Biological removal of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins from incinerator fly ash by Sphingomonas wittichii RW1. Water Res 39:4651–4660. 10.1016/j.watres.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nam IH, Kim YM, Schmidt S, Chang YS. 2006. Biotransformation of 1,2,3-tri- and 1,2,3,4,7,8-hexachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin by Sphingomonas wittichii strain RW1. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:112–116. 10.1128/AEM.72.1.112-116.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkes H, Wittich R, Timmis KN, Fortnagel P, Francke W. 1996. Degradation of chlorinated dibenzofurans and dibenzo-p-dioxins by Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:367–371. 10.1128/AEM.62.2.367-371.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreno-Forero SK, van der Meer JR. 2015. Genome-wide analysis of Sphingomonas wittichii RW1 behaviour during inoculation and growth in contaminated sand. ISME J 9:150–165. 10.1038/ismej.2014.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coronado E, Roggo C, van der Meer JR. 2014. Identification of genes potentially involved in solute stress response in RW1 by transposon mutant recovery. Front Microbiol 5:585. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Megharaj M, Wittich RM, Blasco R, Pieper DH, Timmis KN. 1997. Superior survival and degradation of dibenzo-p-dioxin and dibenzofuran in soil by soil-adapted Sphingomonas sp strain RW1. Appl Microbiol Biotech 48:109–114. 10.1007/s002530051024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keim T, Francke W, Schmidt S, Fortnagel P. 1999. Catabolism of 2,7-dichloro- and 2,4,8-trichlorodibenzofuran by Sphingomonas sp strain RW1. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 23:359–363. 10.1038/sj.jim.2900739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruzzini AC, Bhowmik S, Yam KC, Ghosh S, Bolin JT, Eltis LD. 2013. The lid domain of the MCP hydrolase DxnB2 contributes to the reactivity toward recalcitrant PCB metabolites. Biochemistry 52:5685–5695. 10.1021/bi400774m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keen NT, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. 1988. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 70:191–197. 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanier RY, Palleroni NJ, Doudoroff M. 1966. The aerobic pseudomonads: a taxonomic study. J Gen Microbiol 43:159–271. 10.1099/00221287-43-2-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1987. Molecular cloning, a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dennis JJ, Zylstra GJ. 1998. Plasposons: modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:2710–2715. 10.1128/AEM.64.7.2710-2715.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim E, Zylstra GJ. 1999. Functional analysis of genes involved in biphenyl, naphthalene, phenanthrene, and m-xylene degradation by Sphingomonas yanoikuyae B1. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 23:294–302. 10.1038/sj.jim.2900724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Figurski DH, Helinski DR. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76:1648–1652. 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dennis JJ, Zylstra GJ. 1998. Improved antibiotic-resistance cassettes through restriction site elimination using Pfu DNA polymerase PCR. Biotechniques 25:772–776. 10.2144/98255bm04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]