Abstract

Objective:

Work-life balance (WLB) is an essential precursor of workers’ mental health. The theory of rational emotive behaviour therapy proposes that an imbalance in work and family life may result from people's dysfunctional perceptions of their work and other aspects of their personal life. Also, the constructive philosophies of rational emotive behavior therapy are said to be congruent with most religious belief systems of Christian clients. Therefore, our research examined the efficacy of Christian religious rational emotive behaviour therapy (CRREBT) on WLB among administrative officers in Catholic primary schools.

Methods:

This is a group randomized trial involving 162 administrative officers from Catholic primary schools in Southeast Nigeria. The treatment process involved an 8-session CRREBT programme.

Results:

The scores for WLB of the administrative officers enrolled in the CRREBT programme were significantly improved compared to those in the control group at the end of the study. At the follow-up phase, the CRREBT programme proved to be effective over a 3-month period.

Conclusion:

CRREBT is an effective therapeutic strategy for managing WLB among Catholic school administrative officers.

Keywords: administrative officers, Catholic primary schools, Christian religious rational emotive behaviour therapy, religious rational emotive behaviour therapy, work-life balance

1. Introduction

Work-life balance (WLB) is the attainment of a reasonable level of control over occupational and family life. WLB refers to the ability of the individual to manage self, time, stress, change, technology, and leisure.[1] Administrative officers’ well-being includes a measure of how they maintain stability in their work and personal life.[2] With that said, an imbalance between professional and family interface among workers often results in work-family conflict and job dissatisfaction.[3,4] Yet, there is the challenge of creating a balance between professional and family life among several working populations, including school administrative officers.

School administrative officers are those staff who carry out administrative duties in the school to ensure the smooth running of the school office and assist in managing school facilities and other staff.[5,6] Most school administrative officers have the responsibilities of managing the school budgets, logistics and events.[5,6] Most school administrative officers are also charged with the duties of keeping school records and making sure the school operates in compliance with applicable laws and regulations[5] especially primary schools. Most school administrative officers’ responsibilities also include hiring, training and advising staff, providing counseling services to students and staff, resolving conflicts, acting as a focal point in communicating with parents, regulatory bodies and the public, partaking in developing the school curriculum, implementing actions that can improve the school, and assisting in redefining and sustaining the vision of the school.[5] The school administrative officers are responsible to the principal or headteacher while assisting in school routines and financial and administrative issues.[6,7]

The inability of school administrative officers to attain WLB could be considered as work-life imbalance (WLI). WLI among school administrative officers could be due to long working hours, organizational challenges, rising student populations, teachers’ insubordination, health issues, and family crises.[8] Administrative officers may also suffer from WLI because of the complexities and sensitive nature of their terms of reference in the job.[8] Recent research shows that there is a strong connection between WLI and poor self-reported health among adult workers.[9]

Research shows that WLB is negatively related to work demands, turnover intentions, and psychological strain.[10] Also, WLB was found to be negatively associated with stress, anxiety, and symptoms of depression.[11] A significant association was also found between WLB and job performance among working adults.[12] However, as observed by Karakose et al, WLB is achievable when the individual can meet both family and work demands.[13]

WLB is an essential precursor of mental health of workers. Drawing from the propositions of the theory of rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT),[14] we theorized, therefore, that work-life imbalance may result from people's dysfunctional perceptions of their work and other aspects of their personal life. As argued by Ellis, basic REBT philosophies are in tune with several religious ideologies and can be employed by therapists who recognize their clients’ religious orientations to demonstrate to the clients how they can religiously dispute their disturbance-inducing beliefs and improve their mental and emotional health.[15] Because our focus was to improve the WLB of administrative officers in Catholic primary schools, we aimed at developing a specialized WLB program based on the constructive philosophies of Christian religious rational emotive behavior therapy (CRREBT).

1.1. CRREBT

On a general note, Ellis talked about religious rational emotive behaviour therapy (RREBT), which is based on the idea that people's absolutistic religious views could be harnessed to help them develop emotionally healthy behaviour.[15] In other words, the RREBT posits that the fundamental REBT philosophies can be given a religious outlook in order to enable individuals with a devout belief in God and absolutistic religious concepts to get better and feel better emotionally. In RREBT, religious-oriented philosophies which are comparable with REBT philosophies are often supported with Scriptural examples or statements from the texts of diverse religions. In RREBT, the emphasis is to demonstrate how REBT philosophies are related to religious-oriented philosophies in terms of unconditional self-acceptance, unconditional other-acceptance, unconditional life-acceptance, high frustration tolerance, the desire rather than the need for achievement and approval, acceptance of self-direction, acceptance of responsibility, philosophy of nonperfectionism, and other mental health goals.[15]

Various forms of RREBT have been created to help clients of different religions. These include but not limited to CRREBT[16–20] and Qur’anic REBT.[21] Because we aimed to assist administrative officers working in Catholic primary school settings, we focused on exploring whether CRREBT would help to improve their WLB. According to REBT practitioners, the constructive philosophies of REBT are congruent with most religious belief systems of Christian clients.[22,23] In the opinion of Ellis, REBT supports and teaches several significant religious views, including those of Christianity. For instance, the Christian philosophy of grace that endorses the acceptance of sinners but not their sins is related to REBT endorsement of self-and other-acceptance.[24,25] It should be clearly understood that REBT theory does not support acts of immorality instead it wholly accepts the individual(s) as a fallible human being who is culpable of such acts.[26] The REBT theory endorses most religious and moral rules that individuals in diverse cultures follow insofar as they do not hold and execute such rules in a compulsive and rigid way.[24]

The CRREBT programme is a faith-based intervention that utilizes the Bible and other Christian religious materials to help clients assess, dispute, and work through their issues.[16,18,27,28] It uses religious imagery, scriptural disputation, or parable-ic disputation and references to Christian theology in assisting clients to achieve mental and emotional health goals.[20,29] REBT practitioners have made several references to chapters and verses in the Bible (eg, Ecclesiastes 7:20, Romans 3:23 and 1 John 1:8) to demonstrate the compatibility of REBT philosophies with Christian religious philosophies.[30] A CRREBT therapist who shares a similar religious heritage with the client(s) can easily anticipate Scriptural contents and religious materials from the client's religious tradition that can be accommodated and integrated into therapy to help the client(s) find a solution to their emotional and behavioral problems.[31]

1.2. Research purpose

This research aimed to ascertain the effect of CRREBT on WLB among administrative officers in Catholic primary schools in Southeast Nigeria.

2. Method

2.1. Ethical statement

The researchers received ethical approval to carry out this research from the Faculty of Education Research Ethics Committee, University of Nigeria. This ethical approval further guided the researchers to strictly adhere to the research principles of the American Psychological Association.

2.2. Design

The group randomized trial was the design of this study. This experimental design allows the subjects to be assigned to groups based on the peculiarity and close monitoring of the effect of an intervention. It was reported that a group randomized trial design is suitable for the categorization of subjects into experimental and control groups for equal representation.[32]

2.3. Measure

The measure used to elicit information from the school administrative officers was the Work-Family Conflict Scale (WFCS).[33] The measure has 18 items structured with response options ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. The subscales are time-based, strain-based, and behavior-based as they interfere with work and family. The time-based subscale was further subdivided into 2: work interference with family (WIF) and family interference with work (FIW). The strain-based subscale was also categorized into WIF and FIW. The last subscale, which is behavioral-based, also had WIF and FIW components. The discriminant validity ranged from 0.24 to 0.83 across the subscales, validating the measure. Internal consistency reliability method through Cronbach alpha statistics was used to obtain the reliability coefficient of 0.85α for WFCS. The reliability outputs for the various subscales include: time-based WIF (0.87 α), time-based FIW (0.79 α), strain-based WIF (0.85 α), strain-based FIW (0.87), behavior-based WIF (0.78 α), and behaviour-based FIW (0.85 α). The validity of WFCS was confirmed in a past study investigating WLB and job satisfaction among teachers.[4]

The researchers modified the WFCS by merging the WIF and FIW in the three subscales of time-based, strain-based, and behavior-based work-life conflicts to meet the characteristic features of administrative officers in the study area. The response options were restructured into 4 categories of strongly agree (4), agree (3), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1). The higher the response option, the higher the work-family conflict recorded by the respondent. Items 1 to 6, 7 to 12, and 13 to 18 measured strain-based and behavior-based work-life conflict, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis and discriminant validity were used to re-validate the measure. The discriminant validity ranged from 0.35 to 0.89 across the subscales, therefore re-validating the measure. Internal consistency reliability method through Cronbach alpha statistics was used to obtain the reliability coefficient of 0.80α for WFCS. The Cronbach alpha of the subscales for time-based (0.71 α), strain-based (0.77 α), and behavior-based (0.79 α) work-life conflict also confirmed the usability and validity of the individual subscale.

2.4. Participants and procedure

The participants were 162 school administrative officers in Catholic primary schools in Southeast Nigeria. The sample size was arrived at using GPower 3.1 program developed by Faul et al.[34] The demographic features of the participants were as follows: sex, marital status, years of experience, educational qualifications, location of the school, number of children, and so on. Table 1 demonstrates detailed information about the participants. The inclusive conditions for participants were: displaying WLI such as role conflict, poor time management, poor self-management, poor technology perception, and so on, consenting to take part in the programme by signing the consent form, and being a substantive school administrative officer. Exclusion conditions were: administrative officers with a devastating health condition, administrative officers that are not up to 6 months in active service, those who are on any leave, those who were undergoing counselling treatment, those that never returned issued consent form, and those who seemed to be very busy and may not accord the necessary attention to the programme.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Demographics | Experimental group % | Control group % | χ2 | P |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 41 (50.62) | 39 (48.15) | 1.03 | .387 |

| Female | 40 (49.38) | 42 (51.85) | ||

| Educational qualification | ||||

| First degree | 31 (38.27) | 33 (40.74) | .89 | .785 |

| Second degree | 35 (43.21) | 38 (46.91) | ||

| PhD | 15 (18.52) | 10 (12.35) | 1.42 | .298 |

| Years of experience | ||||

| 9–11 | 9 (11.11) | 10 (12.34) | ||

| 12–15 | 37 (45.68) | 34 (41.98) | ||

| ≥16 | 35 (43.21) | 37 (45.68) | ||

| Location of school | ||||

| Urban | 46 (56.79) | 39 (48.15) | .71 | .910 |

| Rural | 35 (43.21) | 42 (51.85) | ||

| Marital status | 2.09 | .092 | ||

| Married | 53 (65.43) | 55 (67.90) | ||

| Single | 15 (18.52) | 13 (16.05) | ||

| Divorced | 8 (9.88) | 6 (7.41) | ||

| Cohabitation | 5 (6.17) | 7 (8.64) | ||

| No. of children | ||||

| None | 9 (11.11) | 7 (8.64) | 1.13 | .358 |

| 1–4 | 46 (56.79) | 50 (61.73) | ||

| 5–8 | 18 (22.22) | 13 (16.05) | ||

| ≥8 | 8 (9.88) | 11 (13.58) | ||

| Mean age of the participants | 38.76 ± 4.65 | 37.89 ± 3.71 | ||

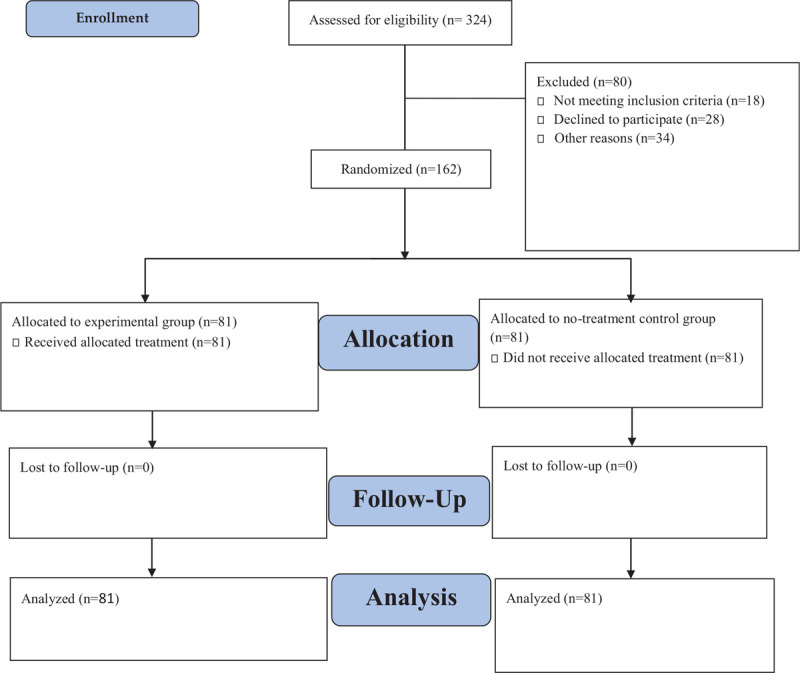

The researchers were able to enroll 162 school administrative officers from 324 officers. The 162 primary school administrative officers were pretested using the WFCS (Time 1). After that, the primary school administrative officers were put in 1 of 2 groups—experimental and no-treatment groups. The experimental group exposed to the CRREBT programme had 81 school administrative officers, whereas the no-treatment group also had 81 primary school administrative officers. The school administrative officers in the experimental group were subdivided into 40 and 41 participants for intensive treatment. The allocation of the administrative officers into groups is portrayed in the consort flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram.

2.5. Treatment programme

We developed a CRREBT programme for improving WLB among Catholic primary school administrative officers after a thorough review of existing literature.[17,23] The CRREBT programme focused on modifying the school administrative officers’ dysfunctional perceptions of their work and their family life. This treatment programme commenced with the setting of religiously related treatment goals connected to issues of WLB among the school administrative officers. The CRREBT techniques employed by the therapists were religious imagery and Scriptural disputation or parable-ic disputation. This treatment programme was such that the participants were met for 1 hour per session. The structure of the treatment programme made provision for relaxation training which was deemed proper in enhancing WLB. For the participants’ good interest, the treatment programme included homework assignments at the end of every session of the treatment. By adapting from a previous treatment protocol of a religiously sensitive REBT, the homework assignments included reviewing the ABCDE model of REBT on a daily basis and studying passages of the Bible about work-family responsibilities and dysfunctions; creating a list of common dysfunctional perceptions about work and family roles; creating a list of Bible passages that are contrary to dysfunctional perceptions about work and family roles; making a list of statements that disprove those dysfunctional perceptions about work and family roles; and allowing clients to select techniques they will practice for homework.[16] The administration of the CRREBT programme took 8 weeks which translated to 8 sessions. English was used to administer the CRREBT programme by 4 group therapists with either master's degree or doctorate in psychological science. The therapists exposed to the study protocol had up to three years of cognate experience in REBT practice.

2.6. Data analyses

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22 was used to conduct the statistical analyses. The researchers employed repeated measures analysis of variance analysis of variance for the analyses of data to determine the between-group and within-group effects. The assumption of the sphericity for repeated measures variance analysis of variance was tested using the Mauchly test of sphericity. The result of the test showed that the assumption of sphericity was not violated. Partial Eta squared (ηp2) was used to report the effect of the CRREBT programme on the WLB scores of the school administrative officers.

3. Results

Table 1 shows that there were no significant differences in the distribution of the school administrative officers by sex, educational qualification, years of working experience, location of school, marital status, and number of children across the experimental and control groups, χ2 = 1.03, P = .387; χ2 = .89, P = .785; χ2 = 1.42, P = .298; χ2 = .71, P = .910; χ2 = 2.09, P = .092; and χ2 = 1.13, P = .358, respectively.

Table 2 shows the mean scores of the school administrative officers in the experimental group (M = 58.11, SD = 4.04) and control group (M = 57.97, SD = 4.05) at the pretest stage as measured by WFCS. As revealed in the Table 2 at the posttest and follow-up phases, the mean scores of the experimental group (M = 29.27, SD = 1.98; M = 29.19, SD = 2.02) improved better than those of the control group (M = 56.97, SD = 6.08; M = 56.88, SD = 6.35) as measured by WFCS.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of the participants’ pretest, posttest and follow-up scores.

| Time group | n | Mean | Standard deviation | 95% CI |

| Pretest | ||||

| Experimental | 81 | 58.11 | 4.04 | 57.21–59.00 |

| Control | 81 | 57.97 | 4.05 | 57.0–58.87 |

| Posttest | ||||

| Experimental | 81 | 29.27 | 1.98 | 28.83–29.71 |

| Control | 81 | 56.97 | 6.08 | 55.62–58.32 |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Experimental | 81 | 29.19 | 2.02 | 28.75–29.64 |

| Control | 81 | 56.88 | 6.35 | 55.48–58.29 |

Table 3 showed significant effect of Time on the WFCS scores of the primary school administrative officers, F (2, 320) = 1665.11, P < .05, ηp2 = 0.91. There was a significant difference in WFCS scores between administrative officers enrolled in the CRREBT group and those in the no-treatment group, F (1, 160) = 923.23, P < .05, ηp2 = 0.85. In other words, the WLB of the experimental group improved over time, implying that CRREBT had a significant effect (85%) on the improvement of the WLB of the experimental group participants.

Table 3.

Tests of within-subjects effect and between-subjects effects as measured by Work-Family Conflict Scale.

| Within-subjects effect | F | Sig | ηp2 |

| Time | 1665.11 | 0.000 | 0.91 |

| Group-by-time interaction | 1440.95 | 0.000 | 0.90 |

| Between-subjects effect | |||

| Group | 923.23 | 0.000 | 0.85 |

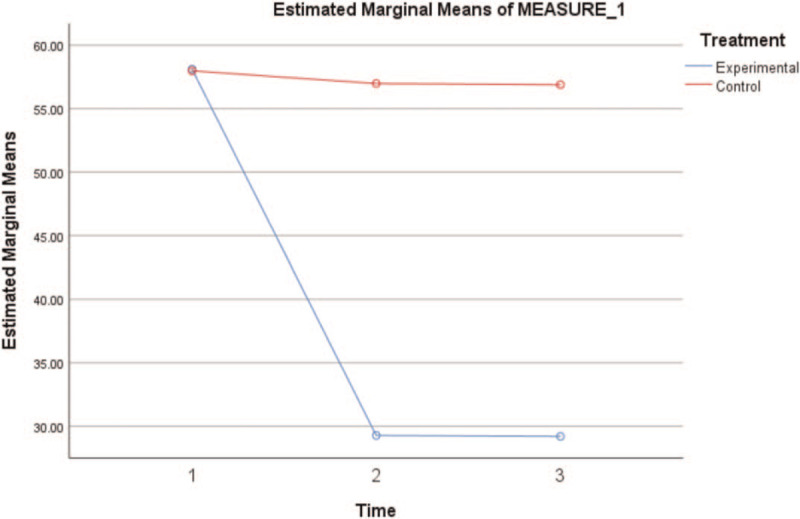

There was also a significant interaction between treatment and time, F (2, 320) = 1440.95, P < .05, ηp2 = 0.90. The nature of the interaction effect of treatment and time is shown in Figure 2

Figure 2.

Interaction graph of time and treatment as measured by Work-Family Conflict Scale.

Table 4 showed that the mean differences in WFCS scores were significant at P < .05 except for the mean differences between Time 2 and 3, and Time 3 and 2 with Ps > .05. This implies substantial and sustained improvements in the WLB of the participants at the posttest and follow-up phases due to CRREBT.

Table 4.

Posthoc analysis of the significant differences in WFCS scores by Time.

| Measure | (I) Time | (J) Time | Mean difference (I-J) | Sig.† | 95% CI |

| WFCS | 1 | 2 | 14.920∗ | 0.000 | 14.050 to 15.790 |

| 3 | 15.000∗ | 0.000 | 14.102 to 15.898 | ||

| 2 | 1 | −14.920∗ | 0.000 | −15.790 to −14.050 | |

| 3 | 0.080 | 0.128 | −0.015 to 0.175 | ||

| 3 | 1 | −15.000∗ | 0.000 | −15.898 to −14.102 | |

| 2 | −0.080 | 0.128 | −0.175 to 0.015 |

4. Discussion

The present study revealed a statistically significant effect of the CRREBT programme on WLB of Catholic primary school administrative officers in the experimental group after the intervention and at the follow-up phase compared to a no-treatment group. The study's finding demonstrates that CRREBT is effective in helping the school administrative officers maintain a balance between work and family life. This finding provides support for the past recognition and application of REBT in helping Christian clients.[18] The use of religiously sensitive REBT, which we termed “CRREBT," for school administrative officers who are Christian clients, is strengthened by previous studies that also applied REBT to assist Christian participants in achieving specific mental and emotional health goals in work and family contexts.[19,35,36] Thus, delivering a religiously sensitive intervention like CRREBT to improve WLB among administrative officers in school settings is essential. According to earlier study findings, individuals who unconditionally accept themselves and who endorse less self-downing beliefs may exhibit reduced levels of emotional distress.[37] An REBT programme can help individuals to achieve these goals.

Other past studies which have also shown the therapeutic benefits of rational emotive behavior interventions in reducing dysfunctional thinking and improving occupational and family health of study participants,[38–45] give credence to our research. To this end, Catholic education authorities could consider using the CRREBT programme to promote WLB among their teaching staff. However, caution must be exercised in interpreting the results of this research. The lack of information about the religious orientation of the study participants is one of the weaknesses of this research. The research was also limited to administrative officers in Catholic primary schools in Southeast Nigeria. The study could not cover teachers and other administrative officers in private and public schools and other regions. As a result, the finding may not apply to administrative officers in those schools and regions. Future studies should endeavor to integrate these categories of teachers and other nonteaching staff in the CRREBT programme. Future studies should also consider providing data on the religious orientation of study participants. There is a need to know whether participants had an implicit or explicit religious orientation to guide the design of future faith-based intervention using CRREBT ideologies.

5. Conclusions

The constructive philosophies of REBT are said to be congruent with most religious belief systems of Christian clients. In the present study, the CRREBT programme showed great promise in the improvement of WLB among administrative officers in Catholic primary schools. Our finding could serve as a therapeutic guide for school counselors working with Christian clients. School counselors may implement CRREBT if they aim to modify the dysfunctional work-family perceptions of school administrative officers to validate the findings of the present study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Leonard Chidi Ilechukwu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Felicia Ezeaku.

Data curation: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Patricia Chinelo Ukaigwe, Okereke Lawrence Okoronkwo, Mary Chinyere Okengwu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Felicia Ezeaku.

Formal analysis: Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Mary Chinyere Okengwu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Felicia Ezeaku.

Funding acquisition: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Leonard Chidi Ilechukwu, Patricia Chinelo Ukaigwe, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Henry D. Ajuzie, Nwamara Chidiebere Isilebo, Augustina Obioma Ede, Ngozi E. Ekesionye, Polycarp Okeke, Okereke Lawrence Okoronkwo, Mary Chinyere Okengwu, Baptista Chigbu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Felicia Ezeaku, Mary Aneke.

Investigation: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Leonard Chidi Ilechukwu, Patricia Chinelo Ukaigwe, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Nwamara Chidiebere Isilebo, Augustina Obioma Ede, Ngozi E. Ekesionye, Polycarp Okeke, Okereke Lawrence Okoronkwo, Mary Chinyere Okengwu, Baptista Chigbu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Mary Aneke.

Methodology: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Leonard Chidi Ilechukwu, Patricia Chinelo Ukaigwe, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Henry D. Ajuzie, Augustina Obioma Ede, Ngozi E. Ekesionye, Polycarp Okeke, Okereke Lawrence Okoronkwo, Mary Chinyere Okengwu, Baptista Chigbu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Felicia Ezeaku, Mary Aneke.

Project administration: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Leonard Chidi Ilechukwu, Patricia Chinelo Ukaigwe, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Henry D. Ajuzie, Nwamara Chidiebere Isilebo, Augustina Obioma Ede, Ngozi E. Ekesionye, Polycarp Okeke, Okereke Lawrence Okoronkwo, Mary Chinyere Okengwu, Baptista Chigbu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Felicia Ezeaku, Mary Aneke.

Resources: Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Patricia Chinelo Ukaigwe, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Henry D. Ajuzie, Nwamara Chidiebere Isilebo, Ngozi E. Ekesionye, Polycarp Okeke, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu.

Software: Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Henry D. Ajuzie, Nwamara Chidiebere Isilebo, Ngozi E. Ekesionye, Polycarp Okeke, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu.

Supervision: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Leonard Chidi Ilechukwu, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Henry D. Ajuzie, Nwamara Chidiebere Isilebo, Augustina Obioma Ede, Polycarp Okeke, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Mary Aneke.

Validation: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Leonard Chidi Ilechukwu, Patricia Chinelo Ukaigwe, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Henry D. Ajuzie, Nwamara Chidiebere Isilebo, Augustina Obioma Ede, Ngozi E. Ekesionye, Polycarp Okeke, Okereke Lawrence Okoronkwo, Mary Chinyere Okengwu, Baptista Chigbu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Mary Aneke.

Visualization: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Henry D. Ajuzie, Augustina Obioma Ede, Ngozi E. Ekesionye, Polycarp Okeke, Okereke Lawrence Okoronkwo, Mary Chinyere Okengwu, Baptista Chigbu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Felicia Ezeaku, Mary Aneke.

Writing – original draft: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Henry D. Ajuzie, Nwamara Chidiebere Isilebo, Augustina Obioma Ede, Ngozi E. Ekesionye, Okereke Lawrence Okoronkwo, Baptista Chigbu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Felicia Ezeaku, Mary Aneke.

Writing – review & editing: Felicia Ukamaka Iremeka, Moses Onyemaechi Ede, Fidelis Eze Amaeze Eze Amaeze, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, Leonard Chidi Ilechukwu, Patricia Chinelo Ukaigwe, Chinyere Dorathy Wagbara, Henry D. Ajuzie, Nwamara Chidiebere Isilebo, Augustina Obioma Ede, Polycarp Okeke, Okereke Lawrence Okoronkwo, Mary Chinyere Okengwu, Baptista Chigbu, Lambert Kenechukwu Ejionueme, Patricia U. Agu, Felicia Ezeaku, Mary Aneke.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CRREBT = Christian religious rational emotive behavior therapy, FIW = family interference with work, P = probability value, REBT = rational emotive behavior therapy, RREBT = religious rational emotive behavior therapy, WFCS = Work-Family Conflict Scale, WIF = work interference with family, WLB = work-life balance, WLI = work-life imbalance.

How to cite this article: Iremeka FU, Ede MO, Amaeze FE, Okeke CI, Ilechukwu LC, Ukaigwe PC, Wagbara CD, Ajuzie HD, Isilebo NC, Ede AO, Ekesionye NE, Okeke P, Okoronkwo OL, Okengwu MC, Chigbu B, Ejionueme LK, Agu PU, Ezeaku F, Aneke M. Improving work-life balance among administrative officers in Catholic primary schools: Assessing the effect of a Christian religious rational emotive behavior therapy. Medicine. 2021;100:24(e26361).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

% = Percentage, χ2 = chi-square, P = probability value.

CI = confidence interval.

CI = confidence interval, WFCS = Work-Family Conflict Scale.

The mean difference is significant at the .05 level.

Adjustment for multiple comparisons: Bonferroni.

References

- [1].Davidson J. Davidson: Work-life balance: What does it entail? June 10, 2016. Accessed April 10, 2022. Available at: https://www.pilotonline.com/inside-business/article_949facde-74e8–55ca-838f-f406950989da.html [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nwankwo L. Conceptual exploration of work-life balance among secondary school administrators in Nigeria. Journal of Educational and Human Management 2018;2:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- [3]. OSHWIKI Networking Knowledge. Work-life balance: Managing the interface between family and work life. 2015. Accessed May 10, 2020. Available at: https://oshwiki.eu/wiki/Work-life_balance_%E2%80%93_Managing_the_interface_between_family_and_working_life. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Maeran R, Pitarelli F, Cangiano F. Work-life balance and job satisfaction among teachers. Interdisciplinary Journal of Family Studies 2013;18:51–72. [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Workable Technology Limited. School Administrator job description. 2020. Accessed February 5, 2020. Available at: https://resources.workable.com/school-administrator-job-description. [Google Scholar]

- [6]. St. Hilary's Primary School. School Administration Officer. 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021. Available at: https://jobs.smartrecruiters.com/StHilarysPrimarySchool/743999684648344-school-administration-officer. [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Public Service Association. School Administrative Officer. 2015. Accessed May 20, 2020. Available at: https://psa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Schools-Administrative-Officer-duties-table.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Staff Management. Is a work-life balance unattainable for school leaders? 2019. Accessed May 10, 2020. Available at: https://www.primaryleaders.com/staff-management/is-a-work-life-balance-unattainable-for-school-leaders. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mensah A, Adjei NK. Work-life balance and self-reported health among working adults in Europe: a gender and welfare state regime comparative analysis. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brough P, Timms C, O’Driscoll MP, et al. Work–life balance: a longitudinal evaluation of a new measure across Australia and New Zealand workers. Int J Hum Resour Manag 2014;25:2724–44. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sprung JM, Rogers A. Work-life balance as a predictor of college student anxiety and depression. J Am Coll Health 2020. 01–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Norzita S, Arrominy A, Zurraini A, et al. Does work-life balance have a relationship with work performance? ASEAN Entrepreneurship Journal 2020;16:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Karakose T, Kocabas I, Yesilyurt H. A quantitative study of school administrators’ work-life balance and job satisfaction in public schools. Pak J Statist 2014;30:1231–41. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ellis A. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy: Revised and Updated. New York: Birch Lane; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ellis A. Can rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) be effectively used with people who have devout beliefs in god and religion? Prof Psychol Res Pr 2000;31:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Johnson W. Christian rational-emotive therapy: a treatment protocol. J Psychol Christ 1993;12:254–61. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Phillips L. Christian rational emotive behavior therapy. Fidei et Veritatis: The Liberty University Journal of Graduate Research 2016;1:Article 4. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Johnson W, Ridley C. Brief Christian and non-Christian rational-emotive therapy with depressed Christian clients: an exploratory study. Couns Values 1992;36:220–9. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Johnson W, Devries R, Ridley C, et al. The comparative efficacy of Christian and secular rational-emotive therapy with Christian clients. J Psychol Theol 1994;22:130–40. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Warnock S. Rational-emotive therapy and the Christian client. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther 1989;7:263–74. [Google Scholar]

- [21].American Psychological Association, Nielsen S. Richards PS, Bergin AE. A Mormon rational emotive behavior therapist attempts Qur’anic rational emotive behavior therapy. Casebook for a Spiritual Strategy in Counseling and Psychotherapy. 2004;213-230. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Johnson W. The comparative efficacy of religious and non-religious rational-emotive therapy with religious clients. Dissertation Abstracts International 1991;52:11A. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Johnson W. Rational-emotive therapy and religiousness: a review. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther 1992;10:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ellis A. My current views on rational-emotive therapy (RET) and religiousness. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther 1992;10:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Johnson B. Chapter 8 rational emotive behavior therapy and the god image. J Spiritual Ment Health 2008;9:157–81. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Springer, Ellis A, Dryden W. The Practice of Rational-Emotive Therapy. 2nd ed1997. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Johnson W, Ridley C, Nielsen S. Religiously sensitive rational emotive behavior therapy: elegant solutions and ethical risks. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2000;31:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nielsen S, Ridley C, Johnson W. Religiously sensitive rational emotive behavior therapy: theory, techniques, and brief excerpts from a case. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2000;31:21–8. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Worthington E, Jr, Sandage S. Religion and spirituality. Psychother Theor Res Pract Train 2001;38:473–8. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nielsen S. Rational-emotive behavior therapy and religion: don’t throw the therapeutic baby out with the holy water!. J Psychol Christ 1994;13:312–1312. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nielsen S. Accommodating religion and integrating religious material during rational emotive behavior therapy. C Cogn Behav Pract 2001;8:34–9. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Routledge, Cohen L, Manion L, Marrison K. Research Methods in Education. 6th ed2007. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Carlson S, Kacmar M, Williams J. Construction and initial validation of multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. J Vocat Behav 2000;56:249–76. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, et al. G∗ Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Balla A. Efficiency of rational emotive behavior religious education in overcoming mourning. Romanian J Sch Psychol 2013;6:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Koening H, Pearce M, Nelson B, et al. Religious vs. conventional cognitive behavioral therapy for major 9 Phillips: Christian Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy depression in persons with chronic medical illness: a pilot randomized trial. J Nerv Ment Dis 2015;203:243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Macavei B, Miclea M. An empirical investigation of the relationship between religious beliefs,irrational beliefs, and negative emotions. J Cogn Behav Psychother 2008;8:01–16. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ogbuanya TC, Eseadi C, Orji CT, et al. Effects of rational emotive occupational health therapy intervention on the perceptions of organizational climate and occupational risk management practices among electronics technology employees in Nigeria. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Onyechi KCN, Onuigbo LN, Eseadi C, et al. Effects of rational-emotive hospice care therapy on problematic assumptions, death anxiety, and psychological distress in a sample of cancer patients and their family caregivers in Nigeria. IInt J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Onyechi KCN, Eseadi C, Okere AU, et al. Effects of Rational-Emotive Health Education Program on HIV risk perceptions among in-school adolescents in Nigeria. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Abiogu GC, Ede MO, Amaeze FE, et al. Impact of rational emotive behavioral therapy on personal value system of students with visual impairment: a group randomized control study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e22333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ede MO, Anyanwu JI, Onuigbo LN, et al. Rational emotive family health therapy for reducing parenting stress in families of children with autism spectrum disorders: a group randomized control study. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther 2020;38:243–71. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Onyishi CN, Ede MO, Ossai OV, et al. Rational emotive occupational health coaching in the management of police subjective well-being and work ability: a case of repeated measures. J Police Crim Psychol 2020;36:96–111. 10.1007/s11896-019-09357-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Abiogu GC, Ede MO, Agah JJ, et al. Effects of rational emotive behavior occupational intervention on perceptions of work value and ethical practices: implications for educational policy makers. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 2021; 10.1007/s10942-021-00389-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Nwokeoma BN, Ede MO, Nwosu N, et al. Impact of rational emotive occupational health coaching on work-related stress management among staff of Nigerian Police Force. Medicine 2019;98:e16724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]