Abstract

Objective

Women’s empowerment and its association with fertility preference are vital for central-level promotional health policy strategies. This study examines the association between women’s empowerment and fertility decision-making in low and middle resource countries (LMRCs).

Design

This cross-sectional study uses the Demographic and Health Survey database.

Settings

53 LMRCs from six different regions for the period ranging from 2006 to 2018.

Participants

The data of women-only aged 35 years and above is used as a unit of analysis. The final sample consists of 91 070 married women.

Methods

We considered two outcome variables: women’s perceived ideal number of children and their ability to achieve preferred fertility desire and the association with women empowerment. Women empowerment was measured by their participation in household decision-making and attitude towards wife-beating. The negative binomial regression model was used to assess women’s perceived ideal number of children, and multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate women’s ability to achieve their preferred fertility desire.

Results

Our study found that empowered women have a relatively low ideal number of children irrespective of the measures used to assess women empowerment. In this study, the measures were participation in household decision-making (incidence rate ratio (IRR): 0.92, 95% CI: 0.91 to 0.93) and attitude towards wife-beating (IRR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.95 to 0.97). In the LMRCs, household decision-making and negative attitude towards wife-beating have been found associated with 1.12 and 1.08 times greater odds of having more than their ideal number of children.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that women’s perceived fertility desire can be achieved by enhancing their empowerment. Therefore, a modified community-based family planning programme at the national level is required, highlighting the importance of women’s empowerment on reproductive healthcare as a part of the mission to assist women and couples to have only the number of children they desire.

Keywords: health policy, public health, health economics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is among the first initiatives to investigate the pooled association between women empowerment and their fertility decisions and their ability to achieve their desired fertility in the context of low and middle resource countries (LMRCs).

The findings are generalisable to women in LMRCs and can assist in creating a central-level promotional health policy to reduce the fertility preference in LMRCs.

This study includes husbands’ influence on women’s perceived and actual fertility, a factor that is barely considered in earlier studies.

Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, this study can only establish the association between women empowerment and fertility rates. However, it is unable to establish any causal effects.

Introduction

Women empowerment has attracted significant attention from researchers, policymakers and practitioners over the last couple of decades, particularly in Asia and Africa. With diverse attributes, empowerment occurs at varying levels from household to global scale.1 2 A consensus is that women empowerment influences reproductive health outcomes, such as fertility, birth interval and contraceptive use.3 4 Women’s empowerment in the form of the ability to make their own choices and pursue goals and control personal living and resources5 6 has been considered crucial in the United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The goals to promote gender equality and empower women in the MDGs (ie, MDG 3) were fine-tuned before inclusion in the SDGs (ie, SDG 4), both of which urged for ending discrimination against women and girls to ensure economic growth and development for a sustainable future.7

Women empowerment is challenging to measure because of its multidimensional nature. Extant literature has assessed empowerment using various measures, including women’s liberty in lone movement,8 the age–education gap between married couples9 and cohabiting partner selection.10 Furthermore, decision-making on household issues that signifies the extent to which women control their surroundings is often used to assess women’s autonomy.11 Finally, women empowerment can also be appraised through their ability to contribute towards household decision-making, including domestic, economic and free movement.12 13

The household decision-making domain is the earliest and most used measure to assess women empowerment,14 which formed the basis of the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) standard questionnaire in the late 1990s. The DHS includes questions about household decision-making, justifying wife-beating by the husband and wife refusal of having sex15 to assess women empowerment in low and middle resource countries (LMRCs).

Given the DHS data’s official launch, substantial research has been conducted involving women empowerment and various health-related outcomes. For instance, studies have demonstrated the association of women empowerment with reproductive health, including contraceptive use,3 12 fertility16–18 and birth intervals.19 In addition, some other pieces of investigation have highlighted the relationships of women empowerment with maternal healthcare service,20 antenatal care,21 children anthropometric status,22 23 infant mortality24 and intimate partner violence.25

To date, few studies have used DHS empowerment measures to interpret its association with fertility preferences. In the sub-Saharan African (SSA) context, greater household decision-making was found associated with a smaller ideal number of children in Guinea,11 Zimbabwe26 and Eritrea.27 A study focusing on Bangladesh with similar empowerment measures found a significant association with unmet fertility desire.17 These results demonstrated that women’s final voice in the daily household purchase has sufficient independent explanatory power to explain fertility preferences beyond traditional measures of women status, for example, education and employment status. Another empowerment measure, negative attitude towards wife-beating, was associated with a small ideal number of children in Guinea and Zambia; however, negative attitude towards refusal of sex was found to be associated with greater odds of having more children than desire in Namibia and Zambia and lower odds than desire in Mali.11 In another study, Atake and Ali constructed a multidimensional empowerment index by using all three empowerment measures in four SSA countries and found that more empowered women in every country desire a fewer ideal number of children.4

Women’s fertility decision is influenced by several external factors other than empowerment and partner influences, such as social norms and cultural context, family and community, particularly in LMRCs. Social norms and cultural beliefs are well known to influence fertility preferences.28 29 For example, cultural attitude and norms towards reproduction in some societies in Africa and South Asia are based on the assumption that children are the sources of old age financial support and alternative strength in case of child death and that larger family size is prestigious, which encourages high fertility preferences.18 30 Furthermore, the family tradition of early marriage and pressure from the in-laws’ family are also associated with high fertility choice31

The association of socio-economic and decision-making freedom of women with pregnancy prevention measures, conjugal violence and medical services on fertility has been found to decline either for a single or a coalition of nations.4 11 12 17 18 However, the association of fertility desire and the achievement of fertility choice in the context of LMRCs have not been examined. The UN and other global bodies actively promote the concept of smaller family size to ensure a concentrated effort on fewer children to secure better food, education and health services, which would result in a thriving future overall.32 Assessing the connections between women empowerment and their fertility intention and the achievement of their fertility choice to promote central-level family planning and promotional health programmes in LMRCs are of equal importance. By improving the social status of women and empowering them, society may enjoy several benefits.

Evidence in the extant literature is insufficient to establish a connection between women empowerment and perceived fertility decision, and the ability to achieve that desire, especially in LMRCs. Furthermore, the results of earlier research are inconsistent across countries and regions. Thus, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the association between women empowerment and fertility preferences in LMRCs, the authors aim to investigate the above association using the DHS indicators while controlling for socio-economic and demographic features. Given that the husband’s decision strongly influences a couple’s childbearing behaviour,33 34 this study also examines how the husband’s fertility decision is associated with the wife’s perceptions about the number of children. This study can contribute to the creation of central-level promotional health policy to ensure reduced fertility preference and to achieve the desired fertility in LMRCs through equitable gender roles in the decision-making process, increased awareness and enhanced motivation. Given that birth control remains a huge challenge in most LMRCs, promotional health policy is necessary.

Materials and methods

Setting and data sources

The data were collected from the DHS website (https://www.dhsprogram.com). The standard DHS survey, typically conducted in 5-year interval in selected LMRCs, provided large and nationally representative cross-sectional surveys of 5000–30 000 households.35 Female respondents with an age range of 15–49 years (ie, the reproductive age) were directly interviewed about their literacy, employment history, decision-making capacity, fertility and fertility preferences, pregnancy prevention tools and other related topics.15 The DHS followed guided data collection methods, reliability and validation assessments.36 The DHS developed the concept of the ‘recode’ file aimed to facilitate the analysis. In general, seven ‘recode’ files were provided together with the core questionnaires. Given that the role of husbands in fertility desire is vital, this study selected ‘matched couples’ from DHS recode file.11

Study participants

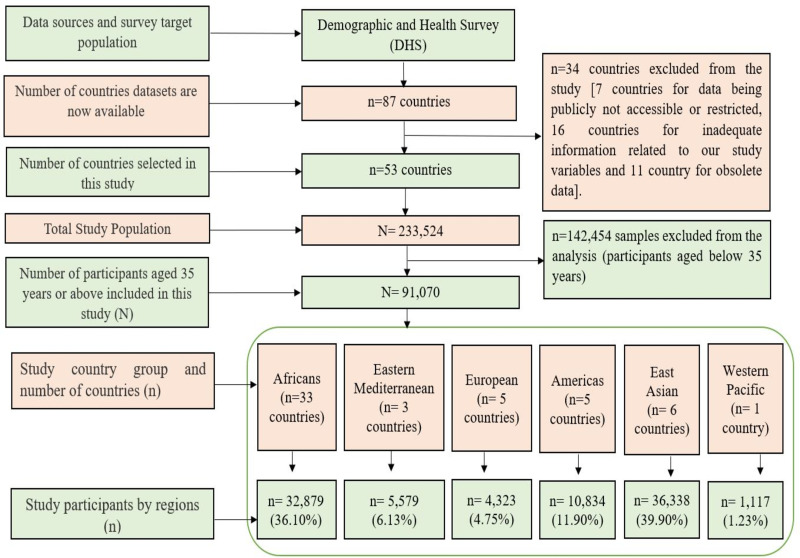

The data of women aged 35 years and above were used as a unit of analysis following prior studies.4 11 The reason for such age restriction is to separate young women who may not have completed their childbearing tenure. The study selected 53 out of 87 countries from six different regions classified by the WHO.37 The remaining 34 countries were excluded from the analysis because their data are publicly inaccessible, inadequate and obsolete. The final sample was limited to 91 070 married women, aged 35 years and above, living with their husbands for the period ranging from 2006 to 2018 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of study participants.

Outcome variable

The preliminary outcome variable for the research was attributed to women’s perception regarding the number of children they wish to ideally conceive. In the DHS questionnaire, to determine the optimal number of children a woman may wish to bear, every married female respondent was hypothetically requested to position themselves at the time before they gave birth and to choose the exact number of offspring they would wish to have in their entire lifetime. Women who have borne no children were asked for a similar response, although without considering any existing children. In each question, non-numerical responses were permitted, for example, God’s wishes. In this study, a non-numerical response is a continuous variable that consists of 3.73% of the total participants. Researchers have recommended the inclusion of non-numerical responses to analyse the desire for family size.26 Few studies have found a lack of a statistically significant difference in the indicators of empowerment for the two groups of responses (ie, numerical and non-numerical).4 11 Thus, to avoid bias, non-numerical responses were considered and recorded as the mean value for the overall sample, which is consistent with the earlier literature.4 11 26

The second outcome variable is the ability of women to achieve their preferred fertility. The processing of this variable is achieved through the difference between the actual number of living children and the ideal number of children perceived by the respondent.4 11 If the difference is greater than zero, the woman is coded as having more children than her stated ideal number, and if the difference is zero or less than zero, the woman is considered a preferred fertility achiever.

Exposure variables

This study detects women empowerment by identifying two markers from the standard questionnaire developed by DHS, namely, the women’s participation in the decision-making of households and attitude towards physical abuse of the wife.4 11 27 However, given the incomplete data set, the third empowerment domain attitude towards refusing sex was not included in this study.

Women’s role in household decision-making

Female members’ involvement in decision-making within their households affects the individual’s reproductive desires and preferences;38 thus, decision-making ability is an exposure variable. The DHS standard questionnaire inquires of each married woman about their final decision-making roles in four key areas: medical health, key household purchases, domestic procurements for everyday requirements and visits to family and other relatives. The data relating to domestic purchases for daily consumption were found in a limited manner in few countries and thus excluded from the analysis. Possible respondent answers are ‘woman alone’, ‘woman jointly with others’, ‘husband alone’ and ‘others alone’. This study recorded any voice of women (either alone or jointly) in all three decisions as a new dichotomous variable because this response reflects higher empowerment compared with any other decision-making combinations.

Attitude towards wife-beating

The study by the DHS also raises the issues of the annoyance and anger incited in the husband by his wife’s activities. It extrapolates the opinion of whether it can be validated for a husband to physically assault his female partner in some scenarios: What if she leaves home without informing him? What if she is negligent towards their offspring? What if she quarrels with the male partner? What if she declines to engage in sexual relations with the husband? What if she burns the meal?’ A dichotomous variable was generated; those who said ‘no reason’ was justified in any of the five situations reflect higher empowerment than those who said that at least one or more reason/s are justified.

Husband’s influence

The husband’s influence on the fertility rate was considered one of the key exposure variables for this analysis. Therefore, this study assessed the optimal number of offspring from the husband’s perception coded in the DHS as a continuous variable. The questions inquired from the husbands were similar to those asked of their wives, and the mean value replaced non-numerical answers.

Other covariates

Other relevant confounder variables were also selected after analysing published documents on women empowerment and fertility desire,4 11 18 39 40 along with the DHS data set. Bivariate analysis was conducted, and the covariates were included later in the fully adjusted model if found significant at 5% or less.

This study also included gender-related variables, such as interpersonal age and educational differences, women’s age at first marriage, problems in obtaining permission to seek healthcare and contraceptive decisions.11 41 42

The present study attempted to incorporate most of the social, demographic and economic variables used in other studies, such as types of residence, household wealth, women education status, polygamous unions, number of living children and experience with any media exposure (ie, television, radio and newspaper/magazine) about family planning.4 11 27 40–43

Estimation strategy

A pooled data set of the 53 LMRCs and subsequent observations of women aged 35 years and above are constructed for analysis. Selecting women above 35 years allows for the segregation of young women who may not have completed their childbearing tenure.4 11 The study first carried out a descriptive analysis to describe the three indicators of women empowerment: women’s ideal number of children; husband’s ideal number of children; gender-related variables and other social, economic and demographic factors in the form of mean, SD, frequency (n) and percentage.

Subsequently, the negative binomial regression model (NBRM) was used to investigate whether women empowerment and the husband’s perceived ideal number of children have any association with the ideal number of children perceived by women aged 35 years or above after controlling for social, economic and demographic variables. Although the ordinary least squares estimation is used in previous research,11 the present study used the NBRM with statistical benefits over simple linear regression.4 44 45 Furthermore, the NBRM assumes unequal mean and variance and is principally correct for over depression in the data (ie, the variance is greater than the conditional mean).18 46 The statistical model developed to capture the association is as follows:

| (1) |

In Equation 1, represents the ideal number of children that a woman desires, is the indicator of women empowerment, is the husband’s perception of the ideal number of children, represents the vector of the socio-economic and demographic characteristics and is the error term.

In the first regression, adjusted and unadjusted models are used to analyse the potential factors that significantly influence women’s fertility preference. The outcome variable (women’s perceptions about their ideal number of children) is continuous. The predictor variables in the unadjusted model that are significant at ≤5% risk level are included in the adjusted model to avoid the effect of potential confounding variables. The results are demonstrated in the form of the incidence rate ratio (IRR) for each variable. This study set a p value at <0.05 level for statistical significance.

Finally, to examine the association between empowerment and women’s ability to achieve their desired family size, this study used multivariable logistic regression to explore the probability of having more than their ideal number of children. Similar to the previous model, all the variables used in the earlier analyses were integrated as explanatory variables. This study attempts to avoid the possible multicollinearity issue by carrying out a variance inflation factor test (not shown) and found no correlation among the explanatory variables. The results of this model are expressed as an OR and a p value at <0.05 level for statistical significance.

Patient and public involvement

We had no contact with any patients or the public for this study.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample

Fertility preferences

Table 1 reports the survey years, sample size, the mean ideal number of children and the SD for the sampled countries. Overall, the mean value of the ideal number of children perceived by women for all countries was 3.89. However, the women’s perception of the mean ideal number of children varied across regions, with the highest figure being in Africa (5.71) and the lowest in Europe (2.82). Among the countries, women from Niger expressed the highest ideal number of children (9.99), whereas women from Ukraine stated the lowest ideal number of children (2.12).

Table 1.

Distribution of women ideal number of children across 53 countries

| Country | Survey year | Sample size | Women’s ideal number of children | |

| (Mean)* | SD | |||

| Overall | 3.89 | 2.54 | ||

| African region | 5.71 | 2.86 | ||

| Angola | 2015–2016 | 715 | 6.51 | 2.76 |

| Benin | 2017–2018 | 1351 | 5.82 | 2.56 |

| Burkina Faso | 2017–2018 | 1560 | 6.40 | 2.23 |

| Burundi | 2016–2017 | 1382 | 4.13 | 1.68 |

| Cameroon | 2011 | 997 | 6.51 | 3.06 |

| Chad | 2014–2015 | 886 | 7.65 | 3.61 |

| Comoros | 2012 | 304 | 5.62 | 2.68 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 2011–2012 | 707 | 6.41 | 2.63 |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 2013–2014 | 1475 | 7.14 | 3.17 |

| Eswatini | 2006–2007 | 225 | 3.00 | 1.69 |

| Ethiopia | 2016 | 1960 | 5.50 | 3.14 |

| Gabon | 2012 | 822 | 5.44 | 2.62 |

| Gambia | 2013 | 384 | 6.60 | 2.61 |

| Ghana | 2014 | 807 | 5.06 | 2.08 |

| Kenya | 2014 | 1638 | 4.07 | 1.98 |

| Lesotho | 2014 | 273 | 3.35 | 1.62 |

| Liberia | 2013 | 582 | 5.84 | 2.72 |

| Madagascar | 2008–2009 | 1620 | 5.36 | 2.53 |

| Malawi | 2015–2016 | 1069 | 4.45 | 1.75 |

| Mali | 2012–2013 | 901 | 6.44 | 2.72 |

| Mozambique | 2011 | 668 | 6.31 | 2.60 |

| Namibia | 2013 | 671 | 4.01 | 2.32 |

| Niger | 2012 | 807 | 9.99 | 3.42 |

| Nigeria | 2018 | 2762 | 6.49 | 3.26 |

| Rwanda | 2014–2015 | 1094 | 4.10 | 1.82 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 2008–2009 | 319 | 4.17 | 1.90 |

| Senegal | 2010–2011 | 1286 | 5.25 | 2.20 |

| Sierra Leone | 2013 | 635 | 5.97 | 2.59 |

| South Africa | 2016 | 322 | 3.10 | 1.51 |

| Togo | 2013–2014 | 876 | 5.10 | 2.11 |

| Uganda | 2016 | 683 | 5.99 | 2.59 |

| Zambia | 2018 | 2034 | 5.83 | 2.27 |

| Zimbabwe | 2015 | 1064 | 4.73 | 1.96 |

| Eastern Mediterranean region | 4.98 | 2.31 | ||

| Afghanistan | 2015 | 3082 | 5.61 | 2.34 |

| Jordan | 2017–2018 | 1401 | 4.17 | 1.91 |

| Pakistan | 2017–2018 | 1096 | 4.03 | 2.08 |

| European region | 2.82 | 1.19 | ||

| Albania | 2017–2018 | 1668 | 2.60 | 0.95 |

| Armenia | 2015–2016 | 607 | 2.79 | 0.87 |

| Azerbaijan | 2006 | 776 | 2.85 | 1.04 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2012 | 542 | 4.43 | 1.46 |

| Ukraine | 2007 | 730 | 2.12 | 0.71 |

| Region of the Americas | 2.93 | 1.69 | ||

| Bolivia | 2008 | 1207 | 2.86 | 1.72 |

| Colombia | 2015 | 5859 | 2.64 | 1.55 |

| Dominican Republic | 2013 | 1574 | 3.42 | 1.85 |

| Guyana | 2009 | 679 | 3.23 | 1.73 |

| Haiti | 2016–2017 | 1515 | 3.46 | 1.71 |

| South-East Asian region | 2.52 | 1.22 | ||

| Bangladesh | 2011 | 1123 | 2.37 | 0.79 |

| India | 2015–2016 | 27 427 | 2.37 | 1.06 |

| Indonesia | 2017 | 4742 | 2.85 | 1.22 |

| Myanmar | 2015–2016 | 1230 | 3.05 | 1.51 |

| Nepal | 2016 | 912 | 2.34 | 0.88 |

| Timor-Leste | 2016 | 904 | 4.84 | 2.61 |

| Western Pacific region | 3.73 | 1.31 | ||

| Cambodia | 2014 | 1117 | 3.73 | 1.31 |

*Non-numerical responses considered as a mean ideal number of children.

Women empowerment

Table 2 describes the selected measures of women empowerment in matched couples for LMRCs. Among the participants, around 61% have a voice in all household decisions either alone or jointly with their husbands. In addition, about 58% of the women agree that husbands should not be allowed to beat their wives for any reason. In the case of husbands, the ideal number of children seems higher (4.64) than those of women. For most of the women, permission to seek healthcare purposes (83.5) is not a big problem.

Table 2.

Selected measures among women in matched couples in 53 low and middle resource countries, Demographic and Health Survey 2006–2018

| Variables | Percentage/mean |

| Husbands’ ideal number of children (mean)* | 4.64 |

| Decision-making† | |

| Any voice of women in all three decisions (%) | 61.14 |

| Women voice count in household decision (0–3) (mean) | 2.23 |

| Attitudes toward wife-beating‡ | |

| No reason is rationalised for wife-beating (%) | 57.34 |

| Count of reasons for which wife-beating is rationalised (0–5) (mean) | 3.8 |

| Gender-related variables | |

| Interspousal age difference (mean years) | 4.72 |

| Interspousal education difference (mean years) | 0.27 |

| Age at first marriage (mean) | 19.5 |

| Going to healthcare centre is permitted (%) | 83.5 |

| Contraceptive decision | |

| Wife has taken alone or jointly | 91.41 |

| Socio-economic and demographic characteristics | |

| Residence (%) | |

| Rural | 60.95 |

| Urban | 39.05 |

| Household wealth index (%) | |

| Poorest | 17.46 |

| Poor | 19.41 |

| Middle | 19.89 |

| Rich | 20.86 |

| Richest | 22.38 |

| Education (%) | |

| No education | 35.96 |

| Primary | 26.66 |

| Secondary and more | 28.14 |

| Higher | 9.23 |

| Polygamous union (%) | |

| No | 88.34 |

| Yes | 11.66 |

| No. of living children (%) | |

| 0 | 2.61 |

| 1–2 | 29.88 |

| 3–4 | 34.80 |

| 5 and more | 32.71 |

| Any media exposure on family planning§ | |

| No | 49.79 |

| Yes | 50.21 |

| Employment status | |

| No work in last 1 year | 41.17 |

| At least work in last 1 year | 58.83 |

*Non-numerical replies added as mean of preferred number of children.

†Final say of women either alone or jointly with husband regarding own healthcare, household purchase and family visit and kin.

‡Whether a husband is justified in beating his wife if she goes out without telling him, negligent towards their offspring, a quarrel with the male partner, declines to engage in sexual relations with the husband or burns the meal.

§Any exposure of media like radio, television and newspaper regarding family planning in last 1 year.

Empowerment and women’s ideal number of children

Table 3 presents the estimates of the pooled association between women empowerment and fertility rate after controlling for the husbands’ influence, gender-related variables and the socio-demographic and economic characteristics. The pooled results of the NBRM for LMRCs show a statistically significant inverse relationship between all empowerment indicators and the women’s perceived ideal number of children. This result indicates that women with high levels of empowerment expect fewer children than the ideal number, which matches the study expectations. In all three decisions, women express an ideal number of children that is 8% lower (IRR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.91 to 0.93) than their counterparts. Furthermore, women who agree that no reason is justified for wife-beating express 4% lower the ideal number of children (IRR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.95 to 0.97). Meanwhile, another exposure variable of interest in this model, the husband’s perceived ideal number of children, show a significant positive association with women’s perception of the ideal number of children (IRR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.04). The authors also constructed sensitivity analysis to see the regional variation, which is presented in online supplemental appendix 1. In the form of empowerment measure, women empowerment is not consistently associated with the ideal number of children in all regions.

Table 3.

Negative binomial regression model examining the association between women’s empowerment and the ideal number of children for low and middle resource countries

| Dependent variable: women ideal number of children | Unadjusted | Adjusted |

| Women’s empowerment | IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) |

| No voice of women in all three decisions (ref) | ||

| Has any voice in three household decision | 0.76† (0.75 to 0.77) | 0.92† (0.91 to 0.93) |

| At least one reason is rationalised for wife-beating (ref) | ||

| No reason is rationalised for wife-beating | 0.83† (0.82 to 0.84) | 0.96† (0.95 to 0.97) |

| Husband’s influence | ||

| Husband’s preferred number of offspring | 1.05† (1.04 to 1.06) | 1.03† (1.02 to 1.04) |

| Socio-economic and demographic characteristics | ||

| Age difference | 1.02† (1.01 to 1.03) | 0.97† (0.96 to 0.98) |

| Educational difference | 1.04† (1.03 to 1.05) | 0.90† (0.89 to 0.91) |

| Age at first marriage | 0.98† (0.97 to 0.99) | 0.90† (0.88 to 0.92) |

| Going to healthcare centre is not permitted (ref) | ||

| Going to healthcare centre is permitted | 0.84† (0.83 to 0.85) | 0.95† (0.94 to 0.96) |

| Women education | ||

| No education (ref) | ||

| Primary | 0.84† (0.83 to 0.85) | 0.97† (0.96 to 0.98) |

| Secondary | 0.64† (0.63 to 0.65) | 0.90† (0.89 to 0.91) |

| Higher | 0.57† (0.56 to 0.58) | 0.90† (0.88 to 0.92) |

| Residence type | ||

| Urban (ref) | ||

| Rural | 1.29† (1.28 to 1.30) | 1.01* (0.99 to 1.02) |

| Wealth index | ||

| Poorest (ref) | ||

| Poor | 0.91† (0.90 to 0.92) | 0.98† (0.97 to 0.99) |

| Middle | 0.85† (0.84 to 0.86) | 0.97† (0.96 to 0.98) |

| Rich | 0.79† (0.78 to 0.80) | 0.97† (0.96 to 0.98) |

| Richest | 0.69† (0.68 to 0.70) | 1.01† (0.99 to 1.02) |

| Role of media on family planning (radio, television or newspaper) | ||

| No exposure (ref) | ||

| At least any exposure | 0.79† (0.78 to 0.80) | 0.93† (0.92 to 0.94) |

| Polygamous union | ||

| No (ref) | ||

| Yes | 1.60† (1.58 to 1.62) | 1.11† (1.10 to 1.12) |

| Employment status | ||

| No work in the preceding year (ref) | ||

| At least work in preceding year | 1.16† (1.15 to 1.17) | 1.10† (1.09 to 1.11) |

| Women living children | ||

| No children (ref) | ||

| 1–2 | 0.85† (0.83 to 0.88) | 0.91† (0.88 to 0.93) |

| 3–4 | 1.20† (1.17 to 1.24) | 1.19† (1.16 to 1.23) |

| 5+ | 1.88† (1.83 to 1.93) | 1.58† (1.54 to 1.62) |

| Wife contraceptive decision | ||

| No decision (ref) | ||

| At least any decision | 0.90† (0.88 to 0.91) | 0.95† (0.94 to 0.97) |

*P<0.05.

†P<0.001.

IRR, incidence rate ratio; ref, reference.

bmjopen-2020-045952supp001.pdf (61.6KB, pdf)

This study relates the current women employment domains to the retrospective information of the ideal number of children and the ability to achieve the ideal number of children to address the research question. The indicators that were found as important drivers in the earlier studies may not have equal importance in the future because of change in indicator-fertility desire associations. Furthermore, without considering some of the retrospective covariates during a woman’s peak childbearing years, addressing a holistic research question such as how empowerment changes over the time of a women’s life is extremely challenging to answer because of the cross-sectional design of this study.

Empowerment and unmet desired number of children

Table 4 presents the findings from the logistic regression model. The results show the adjusted association of the unmet desired number of children with women empowerment-related indicators and the husband’s match with wife in terms of the ideal number of children after controlling socio-economic and demographic factors. For example, women who have a voice in any of the three household decisions are 1.12 times more likely (OR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.16) to have more children than their ideal number compared with their counterparts. Similarly, those who believe that no reason can justify wife-beating are 1.08 times more likely (OR: 1.08, 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.12) to have more children than the ideal number compared with other women.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis examining the association between women’s empowerment and ability to achieve fertility preference for low and middle resource countries

| Dependent variable: women’s ability to achieve fertility desire | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Women’s empowerment | |

| No voice of women in all three decisions (ref) | |

| Has any voice in three household decision | 1.12‡ (1.08 to 1.16) |

| At least one reason is rationalised for wife-beating (ref) | |

| No reason is rationalised for wife-beating | 1.08‡ (1.05 to 1.12) |

| Husband’s Influence | |

| Husband-wife match with preferred offspring (ref) | |

| Husband desire higher preferred offspring than wife | 3.50‡ (3.37 to 3.63) |

| Husband desire lower preferred offspring than wife | 0.68‡ (0.65 to 0.71) |

| Socio-economic and demographic characteristics | |

| Age difference | 0.97‡ (0.97 to 0.98) |

| Educational difference | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) |

| Age at first marriage | 0.93‡ (0.92 to 0.93) |

| Going to healthcare centre is not permitted (ref) | |

| Going to healthcare centre is permitted | 1.09‡ (1.05 to 1.14) |

| Women education | |

| No education (ref) | |

| Primary | 0.93‡ (0.89 to 0.97) |

| Secondary | 0.64‡ (0.60 to 0.67) |

| Higher | 0.37‡ (0.33 to 0.40) |

| Residence type | |

| Urban (ref) | |

| Rural | 1.06† (1.02 to 1.10) |

| Wealth index | |

| Poorest (ref) | |

| Poor | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.02) |

| Middle | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.02) |

| Rich | 0.94* (0.89 to 0.99) |

| Richest | 0.84‡ (0.79 to 0.89) |

| Role of media on family planning (radio, television or newspaper) | |

| No exposure (ref) | |

| At least any exposure | 1.09‡ (1.06 to 1.13) |

| Polygamous union | |

| No (ref) | |

| Yes | 0.42‡ (0.40 to 0.44) |

| Employment status | |

| No work in the preceding year (ref) | |

| At least work in preceding year | 0.92‡ (0.89 to 0.95) |

| Wife contraceptive decision | |

| No decision (ref) | |

| At least any decision | 1.16‡ (1.10 to 1.23)) |

*P<0.05.

†P<0.01.

‡P<0.001.

ref, reference.

Our second exposure variable of interest, the husband’s perceived ideal number of children that is higher than that of the wife, are associated with 3.50 times higher odds (OR: 3.50, 95% CI: 3.37 to 3.63) of having more children than desired as compared with the matched (husband–wife) perception. The authors also constructed sensitivity analysis to see the regional variation, presented in online supplemental appendix 2. The result seems mostly consistent in almost every region where empowered women are likely to have more children than their ideal number of children.

Discussion

According to the results, women empowerment indicators in household decision-making and justifying no reasons for wife-beating are associated with a low ideal number of children among women in LMRCs. The husband’s expectation about the ideal number of children is positively associated with women’s perception of having more children. The results in terms of women empowerment domain (ie, having a voice in all household decisions and no reason is justified for beating wife) are associated with having more children than desire.

Our study revealed that women empowerment, as measured by a voice in household decision-making, is associated with a low perceived ideal number of children. The findings are consistent with prior studies that report household decision-making is inversely associated with a lower perceived ideal number of children in Guinea,11 Eritrea27 and Bangladesh.47 48 However, other studies have found no significant association between household decision-making and women’s perceived ideal number of children.17 The possible reason for this contrast may be the selection of the current sample of women aged 35 years or above. Higher decision-making power with increased age may influence the women to make their own decisions of fertility choice, whereby newly married women usually perform household duties under the primary decision-maker of the family, such as the husband or, in several cases, the mother-in-law.49 Women with greater decision-making power are expected to possess the agency and capacity to recognise their intentions and thus limit their perceived ideal number of children. Thus, the present findings can assist policymakers in achieving greater gains in reducing fertility preference and the desired fertility choice in the LMRCs. By improving women’s decision-making power to secure better food, education and health services, such achievements, can result in a thriving future overall.

However, the findings also reveal that women’s decision-making power is significantly associated with a higher chance of having more children than desired. This result is in line with previous studies, where the authors also found that decision-making power is likely to have unmet fertility desire in Namibia11 and Bangladesh.17 Earlier studies have explained that the situation in which women are taking sole decision-making power means an absent or non-participating partner. In such a case, the sole decision does not indicate empowerment; instead, it means women carry the entire burden of the household responsibilities.11 26

Concerning the perceived ideal number of children, negative attitudes towards wife-beating and the right to refuse sex result in a smaller number of children in many African nations.11 17 The same is reflected in the present study given that negetive attitude towards wife beating strengthen women’s status in their families. The same outcome is likely for other developing countries in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, after creating a women empowerment index, as assessed by the DHS measure, more empowered women desire significantly fewer kids than women less empowered in four African nations of Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Chad.4

Moreover, a negative attitude towards wife-beating is associated with having more children than desired. Earlier studies have found that negative attitudes towards wife-beating were associated with women’s ability to obtain their preferred family size in Mali.11 Possible explanations of the contrasting findings may be that the women misunderstand the different hypothetical situations asked during the survey or provide socially desirable responses. Another explanation by Upadhyay and Karasek is that empowered women personally desire smaller families but often fulfil social or family expectations of higher fertility.11 This paradox may be influenced by the beliefs that children are the sources of old age indemnification, the alternative strength in child death and the prestige to have larger family sizes in certain societies.

Our study also demonstrated that the husband’s perceived ideal number of children is significantly associated with women’s fertility preferences and achievement to maintain their desired fertility. This finding is consistent with the study from the African context where, irrespective of the women’s level of employment, a husband with a smaller ideal number of children ultimately matches women’s fertility preference and achievement of desired family size.11 A possible explanation is that women are coupled with like-minded men or that spouses confirmed each other’s ideas after marriage.11 A study in Pakistan found that the empowerment measure substantially affects contraceptive use when couples consider joint decision-making.12 This finding provides a useful pathway to determine how a husband’s involvement may affect contraception and women’s fertility preference. Knowledge about limiting to the ideal number of children and the corresponding birth interval is essential for men and could be an asset for formulating maternal health policies and family planning programmes.

Our study enriches the current literature by using a large sample of 91 070 married women from 53 countries. Thus, the findings are generalisable to women in LMRCs and can assist in creating central-level promotional health policy to reduce fertility preference and achieve fertility desire in LMRCs through equitable gender roles in the decision-making process, increased awareness and motivation. This study is among the first initiatives to investigate the pooled association between women empowerment and their fertility decisions and the ability to achieve their desired fertility in the context of LMRCs. The large data set provides sufficient power to assess the association between women empowerment and fertility rates. A large pooled data set also helps justify prior findings in a single or group of countries in a specific region. Furthermore, this study includes the husband’s influence on women’s perceived and actual fertility, a factor that is barely considered in earlier studies.

Acknowledging the limitations of the study is of equal importance. First, the DHS explicitly acknowledges the possibilities of a recall bias of retrospective intention measure, such as the ideal number of children,50 which is the primary outcome variable of this analysis. The issue of the ideal number of children is vital in the reproductive analysis; however, given that the answer is self-reported, the quality of data depends on the respondents’ honesty, accuracy and memory volume. Earlier literature has stated that the ideal number of children is upwardly biased because women are reluctant to express a number less than their current number of living children.50 Another problem of the retrospective ideal number of children could be the danger of rationalisation; for example, an unwanted conception may well become a cherished child. Even though some potential problems are found, results from the earlier survey proved plausible where most of the participants were willing to report unwanted conceptions.36 Second, researchers have asked questions regarding the validity of DHS empowerment measures because appropriately answering the questions is challenging given the nature of the questions, which are vague and require a quick guess about general trends in decision-making.11 51 Furthermore, these questions focus on whether or not women take part in the decision-making, and their participation is in any way instrumental (ie, able to influence the outcome).52 Attitude towards the justification of wife-beating, another DHS measure, is criticised because it does not necessarily signify approval of the rights for men; rather, it indicates women’s acceptance of norms that gives men these rights.52 Third, pooling data from multiple countries may result in over-generalising findings across socio-cultural settings. Given that the relationships are rooted in different country-specific social factors, the interpretations of the result should be done with care. The significant association of women empowerment and fertility should not be explained as a causal relationship but rather as symptomatic importance of contextual differences across social and cultural groups. This study recommends future country-level quantitative studies and in-depth qualitative analyses to help resolve some of the discrepancies across the region. Fourth, the DHS questionnaire’s non-numerical response to the question about the ideal number of children is another concern because several respondents provided a non-numeric response. However, such responses are few, and the biases are assumed to be small.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that high women empowerment leads to small family sizes in LMRCs. Family empowerment in the form of decision-making within the household enhances women’s ability to achieve their desired fertility. Husband’s preference for the ideal number of children, women’s education, marital age and wealth or socio-economic status may significantly reduce women’s fertility preference and achieve improved maternal and child health programmes in LMRCs. The family planning programmes in developing countries have been implemented by several institutions, such as the Population Council and International Center for Research on Women. These institutions primarily focus on clinical and hospital-based family planning programmes that are further supplemented by the deployment of trained field health workers but need to consider women empowerment as an enabling factor to achieve desired fertility choice. At the national level, the ministry of health and family affairs needs to prepare revised community-based family planning programmes, highlighting the importance of women’s autonomy on reproductive healthcare, as a part of their mission to assist women and couples to have only the number of children they desire. Substantial reduction in the fertility rate could be achieved if women could have the number of children they consider ideal.

Furthermore, as a policy option, to reduce the dependency on their husbands, women empowerment programmes, such as control over family resources and access to credit and other institutional supports, should be considered. For instance, the protection of the inherent land rights of women and the re-distribution of government-owned land to poor women that guarantees joint ownership of husband and wife need to be ensured through national-level legal policies. Moreover, adult learning and illiteracy elimination programmes, together with access to media targeting married couple, could help achieve fertility desire through overcoming cultural inhibitions and religious opposition towards birth control, thereby attaining gender equality and women empowerment, which are integral to each of the 17 goals of the 2030 Agenda of the UN resolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge MEASURE DHS for their permission to use the Demographic Health Surveys. We are also grateful to the editors and the reviewers who provided constructive comments to help shape this paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceptualised the study: RH and SAK. Contributed during data extraction and analyses: RH. Result interpretation: RH. Prepared the first draft: RH and SMR. Contributed during the conceptualisation and interpretation of results and substantial revision: RH, KA, SMR, SAK and MKA. Revised and finalised the final draft manuscript: RH, KA, SMR, SAK and MKA. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. The data used in this study are freely accessible to the public at the DHS website (https://www.dhsprogram.com/Data/).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Malhotra A, Schuler SR. Women’s empowerment as a variable in international development. In: Narayan D, ed. Measuring empowerment: Cross-disciplinary perspectives. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2005: 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malhotra A, Schuler SR. Women’s empowerment as a variable in International development. World Bank.org 2005:71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaya S, Uthman OA, Ekholuenetale M, et al. Women empowerment as an enabling factor of contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis of cross-sectional surveys of 32 countries. Reprod Health 2018;15:1–12. 10.1186/s12978-018-0658-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atake E-H, Gnakou Ali P. Women’s empowerment and fertility preferences in high fertility countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Womens Health 2019;19:1–14. 10.1186/s12905-019-0747-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samman E, Santos ME. Agency and Empowerment: A review of concepts, indicators and empirical evidence. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI). Research in Progress series 2009. University of Oxford, 2009. Available: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:974e9ca9-7e3b-4577-8c13-44a2412e83bb/download_file?file_format=pdf&safe_filename=Agency%2Band%2Bempowerment%2BA%2Breview%2Bof%2Bconcepts%252C%2Bindicators%2Band%2Bempirical%2Bevidence%2B10a.pdf&type_of_work=Working+paper [Accessed 12 Jun 2020].

- 6.Sen A. Developmet as freedom. Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks, 1999: 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duflo E. Women empowerment and economic development. J Econ Lit 2012;50:1051–79. 10.1257/jel.50.4.1051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Riyami A, Afifi M, Mabry RM. Women's autonomy, education and employment in Oman and their influence on contraceptive use. Reprod Health Matters 2004;12:144–54. 10.1016/s0968-8080(04)23113-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kishor S, Gupta K. Women's in India Empowerment and its states. Econ Polit Wkly 2004;39:694–712. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gage AJ. Women's socioeconomic position and contraceptive behavior in Togo. Stud Fam Plann 1995;26:264–77. 10.2307/2138012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Upadhyay UD, Karasek D. Women's empowerment and ideal family size: an examination of DHS empowerment measures in sub-Saharan Africa. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2012;38:078–89. 10.1363/3807812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hameed W, Azmat SK, Ali M, et al. Women’s empowerment and contraceptive use: the role of independent versus couples’ decision-making, from a lower middle income country perspective. PLoS One 2014;9:e104633. 10.1371/journal.pone.0104633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thapa DK, Niehof A. Women's autonomy and husbands' involvement in maternal health care in Nepal. Soc Sci Med 2013;93:1–10. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyson T, Moore M. On kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behavior in India. Popul Dev Rev 1983;9:35–60. 10.2307/1972894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK. Guide to DHS statistics. Rockville: Maryland UI, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Upadhyay UD, Karasek D. Women’s empowerment and achievement of desired fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. DHS Work Pap No 80 2011;8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akram R, Sarker AR, Sheikh N, et al. Factors associated with unmet fertility desire and perceptions of ideal family size among women in Bangladesh: insights from a nationwide demographic and health survey. PLoS One 2020;15:1–17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0233634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Upadhyay UD, Gipson JD, Withers M, et al. Women's empowerment and fertility: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 2014;115:111–20. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Upadhyay UD, Hindin MJ. Do higher status and more autonomous women have longer birth intervals? results from Cebu, Philippines. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:2641–55. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghose B, Feng D, Tang S, et al. Women’s decision-making autonomy and utilisation of maternal healthcare services: results from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017142–8. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennings L, Na M, Cherewick M, et al. Women’s empowerment and male involvement in antenatal care: analyses of Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in selected African countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:1–11. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai KS, Annim SK, Kulkarni VS, et al. Women’s empowerment and prevalence of stunted and underweight children in rural India. World Dev 2014;62:88–105. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shroff M, Griffiths P, Adair L, et al. Maternal autonomy is inversely related to child stunting in Andhra Pradesh, India. Matern Child Nutr 2009;5:64–74. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00161.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adhikari R, Sawangdee Y. Influence of women’s autonomy on infant mortality in Nepal. Reprod Health 2011;8:1–8. 10.1186/1742-4755-8-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawoko S. Toward intimate partner violence : a study of women in Zambia. Violence Vict 2006;21:645–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hindin MJ. Women's autonomy, women's status and fertility-related behavior in Zimbabwe. Popul Res Policy Rev 2000;19:255–82. 10.1023/A:1026590717779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woldemicael G. Women's autonomy and reproductive preferences in Eritrea. J Biosoc Sci 2009;41:161–81. 10.1017/S0021932008003040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munshi K, Myaux J. Social norms and the fertility transition. J Dev Econ 2006;80:1–38. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrison A, Montgomery E. Life histories, reproductive histories: Rural South African women’s narratives of fertility, reproductive health and illness. J South Afr Stud 2001;27:311–28. 10.1080/03057070120049994 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.May JF. The politics of family planning policies and programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Popul Dev Rev 2017;43:308–29. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00165.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dixit A, Bhan N, Benmarhnia T, et al. The association between early in marriage fertility pressure from in-laws’ and family planning behaviors, among married adolescent girls in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, India. Reprod Health 2021;18:1–9. 10.1186/s12978-021-01116-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United Nations . The millennium development goals report. New York: United Nations, 2015. doi:72.978-92-1-101320-7 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ezeh AC. The influence of spouses over each other's contraceptive attitudes in Ghana. Stud Fam Plann 1993;24:163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bankole A, Singh S. Couples’ fertility and contraceptive decision-making in developing countries: hearing the man’s voice. Int Fam Plan Perspect 1998;24:15–24. 10.2307/2991915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The DHS Program . In: DHS, 2020. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/Where-We-Work/

- 36.Rutstein SO. Guidelines to DHS statistics. Heal (San Fr. Calverton, Maryland). Calverton, MD: ORC Macro, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization . List of member states by WHO region. In: WHO, 2014. Available: https://www.who.int/choice/demography/mortality_strata/en/?fbclid=IwAR1cCDvY_Ss2IrtjTL-Z1YS6o9CuT4ght-tp1xSb0T1VZZYydXbO35ehx34

- 38.Mason KO, Smith HL. Husbands' versus wives' fertility goals and use of contraception: the influence of gender context in five Asian countries. Demography 2000;37:299–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayoub AS. Effects of women’s schooling on contraceptive use and fertility in Tanzania. African Popul Stud 2004;19:139–57. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larsen U, Hollos M. Women's empowerment and fertility decline among the parE of Kilimanjaro region, Northern Tanzania. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1099–115. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00488-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abadian S. Women’s autonomy and its impact on fertility. World Dev 1996;24:1793–809. 10.1016/S0305-750X(96)00075-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amin R, Hill RB, Lii Y. Poor women’s participation in credit-based self-employment: the impact on their empowerment, fertility, contraceptive use, and fertility desire in Rural Bangladesh. Pak Dev Rev 1995;34:93–119. 10.30541/v34i2pp.93-119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jejeebhoy SJ. Women's status and fertility: successive cross-sectional evidence from Tamil Nadu, India, 1970-80. Stud Fam Plann 1991;22:217. 10.2307/1966478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caudill SB. Caudill and Mixon (1995 empirical Econ) modeling household fertility decisions; estimation and testing of censored regression models for count Data.pdf. Empir Econ 1995;20:183–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamaruddin R, Khalili JM. The determinants of household fertility decision in Malaysia; an Econometric analysis. Procedia Econ Financ 2015;23:1308–13. 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00472-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osgood DW. Poisson-Based regression analysis of aggregate crime rates. J Quant Criminol 2000;16:21–43. 10.1023/A:1007521427059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steele F, Amin S, Naved RT. The impact of an integrated micro-credit programme on women’s empowerment and fertility behavior in rural Bangladesh. J Dev Areas 1998;49:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balk D. Individual and community aspects of women’s status and fertility in Rural Bangladesh. Popul Stud 1994;48:21–45. 10.1080/0032472031000147456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dali SM, Thapa M, Shrestha S. Educating Nepalese women to provide improved care for their childbearing daughters-in-law. World Health Forum 1992;13:353-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Casterline JB, El-Zeini LO. The estimation of unwanted fertility. Demography 2007;44:729–45. 10.1353/dem.2007.0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glennerster R, Walsh C. Is it time to rethink how we measure women’s household decision-making power in impact evaluation? In: innovations for poverty action, 2017. Available: https://www.poverty-action.org/blog/it-time-rethink-how-we-measure-women’s-household-decision-making-power-impact-evaluation

- 52.Kishor S, Subaiya L. Understanding women’s empowerment: a comparative analysis of demographic and health surveys (DHS) Data. DHS comp reports no 20, 2008. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/CR20/CR20.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045952supp001.pdf (61.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. The data used in this study are freely accessible to the public at the DHS website (https://www.dhsprogram.com/Data/).