Abstract

Irritability is a common, impairing transdiagnostic symptom in childhood psychopathology, though it has not been comprehensively studied in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Further, the central cognitive behavioral treatment component for OCD, exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP), has been recently proposed as a treatment for irritability. This study aimed to evaluate whether certain clinical characteristics are associated with irritability in pediatric OCD and whether irritability reduces following ERP. Participants were 161 youth (ages 7–17) with OCD and a caregiver participating in a randomized controlled trial of D-cycloserine or pill placebo augmented ERP. Participants completed validated assessments during treatment. Irritability was significantly and positively associated with depressive symptoms, defiance, functional impairment, and family accommodation, was negatively related to responsibility for harm/inflated threat estimation beliefs, but was not associated with pretreatment OCD severity, symptom dimensions, perfectionism/need for certainty, or anxiety. Irritability significantly declined following treatment, with over half of youth with any pretreatment irritability experiencing clinically significant change, though this change was not related to OCD improvement. Results suggest that irritability may be a marker of psychiatric comorbidity, parental accommodation, and impairment in youth with OCD. Implications for the exposure-based treatment of irritability are discussed.

Keywords: OCD, impairment, disruptive behavior, depression, accommodation, youth, pediatric, CBT

Introduction

Irritability is a common transdiagnostic symptom in childhood psychopathology characterized by a proneness to anger, and is composed of both behavioral (e.g., yelling, temper outbursts, aggression) and affective (e.g., feeling angry, annoyed) responses (Brotman, Kircanski, Stringaris, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2017). Traditionally, irritability in youth has been conceptualized as a symptom of other primary diagnoses such as mood disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and bipolar disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). A growing body of research, however, suggests that childhood irritability may merit its own independent investigation and treatment. This has been largely due to a developing understanding of the behavioral and neurobiological mechanisms of irritability (Brotman et al., 2017; Kircanski et al., 2019), as well its association with functional impairment (Copeland et al., 2013; Shimshoni et al., 2020; Stringaris, Cohen, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2009) and negative affect and psychopathology broadly (Beauchaine & Tackett, 2020; Brandes, Herzhoff, Smack, & Tackett, 2019). This growing recognition has resulted in the inclusion of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in DSM-5, a diagnosis that is primarily characterized by a chronic irritable mood with severe temper outbursts, as well as a “chronic irritability” specifier within oppositional defiant disorder in ICD-11 (Reed et al; 2019; Roy, Lopes, & Klein, 2014).

Chronic irritability had been hypothesized to be an indicator of pediatric bipolar disorder in the past (Roy, Lopes, & Klein, 2014) and/or treated as a symptom of disruptive behavior disorders due to the aggressive or noncompliant responses that often accompany an irritable mood (Sukhodolsky, Smith, McCauley, Ibrahim, & Piasecka, 2016). Multiple studies have now shown more consistent associations between chronic, persistent irritability and anxiety and unipolar depression, however, than with bipolar disorder (Stringaris et al., 2009; 2010). For example, childhood irritability has significant shared genetic heritability with unipolar depression and anxiety (Savage et al., 2015) and is independently associated with the later development of anxiety and depressive disorders but not with bipolar disorder (Stringaris et al., 2009; 2010) or “adult” externalizing problems like substance use disorders, antisocial personality disorder (Stringaris et al., 2009), or violence (Althoff, Kuny-Slock, Verhulst, Hudziak, & van der Ende, 2014). Further, although irritability commonly co-occurs with defiant symptoms as in oppositional defiant disorder (e.g., rule-breaking), latent variable analyses have shown its independence from defiance, with strong cross-sectional and longitudinal ties to internalizing symptoms (Althoff et al., 2014; Evans et al., 2019).

Evidence suggests there is a unique association between irritability and anxiety even when controlling for depressive and defiant symptoms (Cornacchio, Crum, Coxe, Pincus, & Comer, 2016). Studies suggest that anxious youth are more irritable than their non-anxious counterparts (Stoddard et al., 2013), with over half of anxious youth estimated to have clinically elevated irritability (Shimshoni et al., 2020). Anxious-irritable youth may represent a unique subgroup associated with more severe symptoms, greater impairment, poorer social skills, and greater parenting stress (Shimshoni et al., 2020).

Irritability has seldom been studied in OCD despite evidence to suggest that it may be a common issue in this population as well. Many experts still consider anxiety as the predominant affect driving OCD despite its reclassification in DSM-5 and ICD-10 outside the anxiety disorder rubric (e.g., Abramowitz, 2018; Norton & Paulus, 2017). OCD and anxiety disorders share overlap in their cognitive-behavioral mechanisms (Abramowitz, 2018; Norton & Paulus, 2017), some of which have clear ties to theoretical models of irritability in youth. Anxiety disorders and OCD are both characterized by overestimations of danger (Coles et al., 2010; Tolin, Worhunsky, & Maltby, 2006) and perfectionism (Limburg, Watson, Hagger, & Egan, 2017), while irritability has been proposed to be a hypersensitive reaction to threat and “frustrative non-reward,” or the absence of a desired outcome despite engaging in behaviors intended to achieve that outcome (Brotman et al., 2017; Kircanski et al., 2019). Accordingly, biased attentional processing of threat has been observed in children with anxiety (Waters & Craske, 2016), irritability (Salum et al., 2017), and adults with OCD (though it is worth noting less consistent associations in this population; Hezel & McNally, 2016). Sensitivity to frustrative non-reward appears to share phenomenological overlap with a need for perfection as well, as things not being “perfect” or “just right” may be experienced as highly frustrating for many youth with OCD. Accordingly, perfectionism has been associated with anger as well as depression and anxiety in children (Hewitt et al., 2002). Further, recent analyses have provided support for a mediational link between irritability and anxiety through intolerance of uncertainty, a central cognitive vulnerability in OCD and anxiety disorders (Evans, Blossom, & Fite, 2020). Finally, temper outbursts and aggression could be considered a “fight” rather than “flight” response to perceptions of threat. Clinical anxiety is often conceptualized as an overactivation of this system in non-threatening situations, corresponding with enhanced sympathetic nervous system activity (Barlow, 2002; McCarty, 2016), and it may be that anxious-irritable youth react in an aggressive rather than avoidant manner when this system is activated.

It follows that the behavioral aspects of irritability (i.e., tantrums, aggression) have been commonly reported in children with OCD and are associated with greater functional impairment and psychiatric symptom burden. For example, one study suggested that over half of children with OCD experience rage attacks, finding that these episodes were significantly related to functional impairment, symptom severity, and increased family accommodation (Storch et al., 2012). Another estimated that over a third of youth with OCD have temper outbursts, significantly more than community controls (Krebs et al., 2013). Although they did not find that temper outbursts were associated with symptom severity in their clinical sample, they did find a significant relationship with depressive symptoms (Krebs et al., 2013). Together, this research suggests that irritability would be expected to be prevalent in children with OCD and associated with OCD symptom severity, obsessive beliefs (i.e., a need for perfection/certainty, responsibility for harm/inflated threat estimations), and psychiatric comorbidity, though this construct has not been specifically studied in this population.

A developing understanding of irritability has led to new cognitive-behavioral treatment conceptualizations as well (Kircanski et al., 2019). Parent management training has addressed irritability through modifying parent responses to behaviors associated with irritability (e.g., tantrums, noncompliance, aggression), while cognitive-behavioral approaches have emphasized emotion identification, social skills, and implementation of cognitive restructuring and emotion regulation strategies (Sukholdosky et al., 2016). Recently, however, investigators have also proposed an exposure therapy-based approach complemented by parent management training for irritability (Kircanski et al., 2019), the key treatment component in childhood OCD and anxiety disorders, termed exposure and response prevention (ERP) in OCD (Ale, McCarthy, Rothschild, & Whiteside, 2015). The developers have hypothesized that systematic exposure to irritability triggers while reducing aggressive responses may facilitate top-down emotion regulation as well as extinction learning (Kircanski et al., 2019). Regardless, irritability has not been investigated as a predictor of response or as an outcome in ERP to date (though Krebs and colleagues [2013] did find a decrease in temper outbursts among children with OCD following a course of cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]). In the context of ERP, it is expected that many exposure tasks may elicit irritable responses, particularly those that provoke feelings of imperfection (e.g., completing homework the “wrong” way), or who are prone to respond to threat in an aggressive way (e.g., if they refuse to complete an exposure they perceive as dangerous), thus engaging extinction learning and emotion regulation processes.

One exciting advance in the exposure therapy field in recent years has been the introduction of D-cycloserine as a potential treatment enhancer (Mataix-Cols et al., 2017). D-cycloserine is a partial agonist of the NMDA glutamate receptor, which is proposed to facilitate extinction learning through increased glutamergic transmission in the amygdala (Mataix-Cols et al., 2017). To the extent that D-cycloserine may facilitate similar extinction learning processes when youth are presented with irritating situations, it may also be that this drug facilitates irritability as well as fear/anxiety improvement. In contrast, some studies have found irritability to be a side-effect of D-cycloserine (albeit at higher doses than they are typically administered during exposure therapy; Durrant & Heresco-Levy, 2014), and glutamate-inhibiting agents have shown efficacy when used as a treatment of irritability in autism spectrum disorder (Nikoo et al., 2015). Together, it is unclear whether D-cycloserine would have a substantial impact on the course of irritability during exposure-based treatment.

The goals of this study were to investigate irritability in the presentation and treatment of pediatric OCD. Specifically, the aims of the study were: 1) to describe the clinical characteristics associated with irritability in pediatric OCD, 2) to evaluate whether irritability is a predictor of ERP treatment outcome for OCD, and 3) to test whether irritability reduces following ERP. Data from a randomized controlled trial of D-cycloserine or pill placebo augmented ERP were analyzed. It was hypothesized that irritability would be positively related to depressive symptoms, defiance, OCD severity, anxiety, parental accommodation and functional impairment. It was also expected that a need for perfection/certainty and overestimations of threat/responsibility for harm would be positively associated with irritability due to prior associations that have been found between anger and perfectionism (Hewitt et al., 2002), irritability and intolerance of uncertainty (Evans, Blossom, & Fite, 2020), and attentional biases towards threat in children with severe irritability (Salum et al., 2017). It was also hypothesized that irritability would predict treatment outcome based on prior research that shows worse treatment outcome for children with OCD and disruptive behavior disorders (Storch et al., 2008b). Last, it was hypothesized that irritability would significantly decline following ERP (Krebs et al., 2013), and would correspond with improvement in OCD severity and the initiation of exposure exercises. Treatment hypotheses were not expected to be moderated based on whether participants received D-cycloserine or placebo based on null findings from the original trial from which the following analyses are conducted (Storch et al., 2016).

Methods

Procedures

This study was a secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial of D-cycloserine or pill placebo augmented ERP (Storch et al., 2016). The institutional review boards at each participating site (Massachusetts General Hospital and University of South Florida) approved the trial. Written parental consent and child assent were obtained at an initial screening visit at which the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children– Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 2000) and Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS; Scahill et al., 1997) were administered. A licensed physician also performed a physical evaluation to determine appropriateness for study inclusion. If eligibility criteria were met, participants then engaged in ten sessions of family-based CBT. Treatment followed an abbreviated version of the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) protocol with a greater emphasis on caregiver involvement (POTS, 2004). The first three sessions focused on psychoeducation, hierarchy development, and cognitive interventions, while sessions 4–10 focused on ERP. Before the first exposure session (CBT session 4), children who continued to meet criteria for OCD were randomized in a double-blind fashion (1:1 allocation ratio) by a computer randomization program to receive either weight-adjusted D-cycloserine or placebo plus exposure therapy for the remainder of treatment. One investigator led randomization and was not involved in clinical care or assessment during the trial, while all clinical personnel were blind to group assignment but not that youth received CBT. The CY-BOCS was administered before every other session, as well as before the seventh CBT session. Other measures were administered at baseline, before CBT session 4, before CBT session 7, and at posttreatment (after CBT session 10). Therapists were masters- or doctoral-level clinicians supervised by licensed psychologists experienced in CBT for OCD. Session checklists, weekly supervision, and evaluation of 20% of audiotapes were used to ensure treatment fidelity. Please refer to Storch and colleagues (2016) for the full study protocol.

Participants

Participants in this analysis were 161 children and adolescents (ages 7–17) with OCD and their parents who were enrolled between June 1, 2011, and January 30, 2015. Sample size was determined to detect a small time by group interaction for the original trial (Storch et al., 2016). Inclusion criteria for the trial were a primary diagnosis of OCD as assessed by the K-SADS-PL (Kaufman et al., 2000), a score of at least 16 on the CY-BOCS (Scahill et al., 1997), and an IQ of at least 85. Exclusion criteria were 1) initiation of an antidepressant medication 12 weeks prior to enrollment, a change in antidepressant dosage 8 weeks prior to enrollment, or initiation or change in antipsychotic medication in the 6 weeks prior to enrollment, 2) presence of epilepsy, renal insufficiency, current or past substance abuse, poor physical health, weight less than 22.5 kg, or an allergy to D-cycloserine, 3) inability to swallow study medication, 4) active suicidality or suicide attempt in the past year, 5) pregnancy or having unprotected sex among female participants, or 6) comorbid diagnoses of psychosis, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorder, anorexia nervosa, or a primary diagnosis of hoarding disorder. Pretreatment analyses were conducted with all child-parent dyads who completed assessments at the second study visit (i.e., after the screening visit), had a CY-BOCS score of at least 16 at that point, and had a primary diagnosis of OCD as assessed by the K-SADS-PL at the initial visit. Treatment outcome analyses were conducted with all participants who were randomized.

Measures

Irritability.

Irritability was measured by summing the following three items from the child behavior checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla), a widely used broadband parent-report measure of child emotional and behavioral functioning: “tantrums or hot temper;” “sudden mood changes;” and “stubborn, sullen, or irritable” (“CBCL-Irritability”). This three-item assessment has been widely used in irritability research (e.g., Althoff et al., 2014; Cornacchio et al., 2016; Salum et al., 2017), and recent psychometric analyses in a mixed clinical sample support the scale’s factor structure, invariance across age and gender, and convergent, divergent, and criterion validity (Evans et al., 2019), as well as excellent test-retest reliability (Tseng et al., 2017). Relative to the youth-report version of this broadband measure, the parent-report has been shown to have superior psychometric properties (Evans et al., 2019). Internal consistency in this sample was α = 0.84.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The CY-BOCS was used to assess OCD (Scahill et al., 1997). The CY-BOCS is a widely-used, interview-administered assessment of OCD symptoms for children and adolescents. The CY-BOCS includes a checklist of common obsessive-compulsive symptoms, followed by a severity section that assesses impairment, distress, control, resistance, and time taken by symptoms. Both the total score and symptom checklist were used in this study; the total score was used to assess overall severity, and summed scores based on the presence of symptoms in different categories were used to assess symptom dimensions. The following symptom dimensions scores were generated following prior research (Storch et al., 2008a): contamination (contamination obsessions and washing compulsions), symmetry (magical thinking obsessions; repeating, counting, and ordering compulsions), harm/aggressive (aggressive and somatic obsessions; checking compulsions), and sexual/religious (sexual and religious obsessions). Internal consistency for the total score was good, α = 0.87.

Defiance.

Defiance was assessed with the following three items from the CBCL: “argues,” “disobeys at home,” and “disobeys at school” (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; Evans et al., 2019). This three-item measure has shown strong convergent, divergent, and criterion validity, invariance across age and gender, and independence from the CBCL-Irritability subscale in a factor analysis (Evans et al., 2019). Internal consistency was acceptable, α = 0.70.

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS; Poznanski & Mokros, 1996), a semi-structured interview that assesses depressive symptoms that has demonstrated excellent internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and interrater reliability (Poznanski & Mokros, 1996). Internal consistency was α = 0.85.

Anxiety.

Anxiety was assessed with the total score of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Connors, 1997). The child-report version of the measure has been widely used and has demonstrated good test-retest reliability, internal reliability, and convergent/divergent validity (March et al., 1997). Internal consistency for all MASC items in this sample was α = 0.94.

Obsessive beliefs.

Cognitive vulnerabilities associated with OCD were assessed using the child-version of the Obsessive-Beliefs Questionnaire (OBQ-CV; Coles et al., 2010), including perfectionism/a need for certainty, responsibility for harm/inflated perception of threat, and importance of/a need for control of thoughts. Preliminary psychometric analysis supports the validity and reliability of the OBQ-CV in children with OCD (Coles et al., 2010). Internal consistency was α = 0.94 for the perfectionism/certainty subscale, α = 0.93 for the responsibility for harm/threat subscale, and α = 0.88 for the importance/ control over thoughts subscale.

Impairment.

Both OCD-specific and overall functional impairment were assessed using child- and parent-report. To assess overall psychiatric impairment the Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS) was used (Bird, Shaffer, Fisher, & Gould, 1993). Internal consistencies were α = 0.87 (parent-report) and α = 0.85 (child-report). The total score from the parent- and child-report versions of the Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale (COIS; Piacentini et al., 2007) was used to assess impairment related to obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Internal consistencies were α = 0.84 (parent-report) and α = 0.87 (child-report).

Family Accommodation.

The Family Accommodation Scale-Interviewer Rated (FAS) was used to assess parental accommodation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. The FAS assesses the frequency of 12 common accommodation behaviors (e.g., assisting with rituals, providing excessive reassurance) in the past week using a 0–4 Likert scale. The scale has shown good construct validity (Calvocoressi et al., 1999). Internal consistency in this sample was α = 0.75.

Analyses

To evaluate clinical characteristics associated with irritability in pediatric OCD, correlations were conducted between the CBCL-Irritability subscale (parent-report), the CBCL-Defiance subscale (parent-report), the CDRS (interview-administered), the CY-BOCS (interview-administered), the CY-BOCS checklist symptom dimensions (symmetry, contamination, taboo/religious, aggressive), the MASC total score (child-report), the OBQ-44 subscale scores (child-report), the FAS (interview-administered), and the parent- and child-report CIS and COIS. The proportion of youth with elevated irritability was also estimated using a cutoff score of 4 on the CBCL-Irritability scale, a score that has been used in treatment outcome research (Evans et al., 2020). A multivariate linear regression predicting the CBCL-Irritability was then conducted, with each variable with significant bivariate relationships with CBCL-Irritability included as independent variables.

A multilevel model (MLM) was conducted to evaluate whether irritability was a significant predictor or moderator of symptom reduction (Singer & Willett, 2003). The CY-BOCS was the dependent variable, using each CY-BOCS measurement (administered at every other session) to track trajectory, along with the following independent variables: time, baseline CBCL-Irritability*time (i.e., whether symptom reduction varies as a function of baseline irritability) and CBCL-Irritability*time*condition (i.e., whether the effect of irritability on symptom reduction is moderated by placebo vs. D-cycloserine). Fixed and random effects of each level 1 variable was reported (time in this analysis). Model fit was determined by evaluating significant reductions in −2 log likelihood (−2LL) coefficients as well as reductions in Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and Schwarz’s Bayesian Criterion (BIC) across each nested model.

To evaluate changes in irritability across treatment, clinical significance analyses as well as an MLM with the CBCL-Irritability subscale as the dependent variable were conducted. The four follow-up CBCL-Irritability assessments were used to track trajectory in irritability across treatment (before CBT sessions 1, 4, 7, and 10). Clinical significance was assessed by evaluating 1) whether patients experienced statistically reliable change and 2) whether they finished treatment in the nonclinical range (Jacobsen & Truax, 1991). A score of less than 4 was considered to be in the “nonclinical range” based on the use of this score to indicate elevated irritability (Evans et al., 2020). The following independent variables were included in the MLM analysis in separate nested models: time (to evaluate if irritability reduces across treatment), time*time (to evaluate a quadratic effect of time, as it was expected that irritability would reduce more beginning at session 4 when exposure began, as reflected in a negative quadratic effect), and time*condition (to evaluate if changes varied by D-cycloserine vs. placebo status). The final model evaluated if changes in clinical variables expected to be related to irritability predicted change in the CBCL-Irritability scale (specifically, FAS, CIS-P, CY-BOCS, and CDRS). Change in each of these variables was calculated by generating each child’s slope in each variable. This was done by conducting a regression for each child with the variable of interest (FAS, CIS-P, CY-BOCS, and CDRS) as the dependent variable and time as the independent variable. The b coefficient corresponding with time was used as the variable’s slope (i.e., rate of improvement in OCD, depression, family accommodation, and impairment for each child). The interaction between each slope variable and time was included in the final nested model in the MLM predicting CBCL-Irritability to evaluate if child-level changes in these variables were associated with change in irritability.

Nested multilevel models were calculated with the following equation: yij = [β0i + β1i(timeij)] + εij to evaluate if they improved on the null model, yij = β0i + εij, or the previous best fitting model (Gallop & Tasca, 2009). In this formula, yij represents the dependent variable (CY-BOCS in the first analysis, CBCL-Irr in the second) for participant i at time j, β0i is the intercept for participant i, β1i is the linear growth rate for individual i across each time point, and εij is the residual error term for each participant i at time j. Calculation of β0i and β1i varied based on predictors in each model: β0i = γ00 + γ01(independent variable) + μ0i; β1i = γ10 + γ11(independent variable) + μ1i, in which γx0 represents the grand mean intercept, γx1 represents the coefficient associated with the independent variable, and μ represents the random variance. Thus, the γ11 coefficient was of central interest when evaluating whether an independent variable had a significant direct relationship with the dependent variable.

Missing data were relatively uncommon, ranging from 0.6%−9.9% missing for any measure. Little’s test for missing completely at random was nonsignificant for the baseline analysis, χ2 (272) = 274.27, p = .45, as well as for the MLM with the CY-BOCS as the dependent variable, χ2 (1) = 0.40, p = .53, and for the MLM with the CBCL-Irritability subscale as the dependent variable, χ2 (2) = 2.76, p = .25 (Little & Rubin, 2002). Because of the low proportion of missing data and nonsignificant Little’s test, baseline analyses were conducted using a case-wise deletion approach, while a full-information maximum likelihood approach was used for longitudinal analyses. Data were generally normally distributed using a cutoff of −2 to +2 for skewness or kurtosis (George & Mallery, 2010), with the exception of the sexual-religious CY-BOCS checklist subscale; this subscale was transformed using the SPSS RankIt function to impose a normal distribution on the data. In light of the number of analyses conducted in this study, significance was interpreted at p < .01.

Results

Sample characteristics

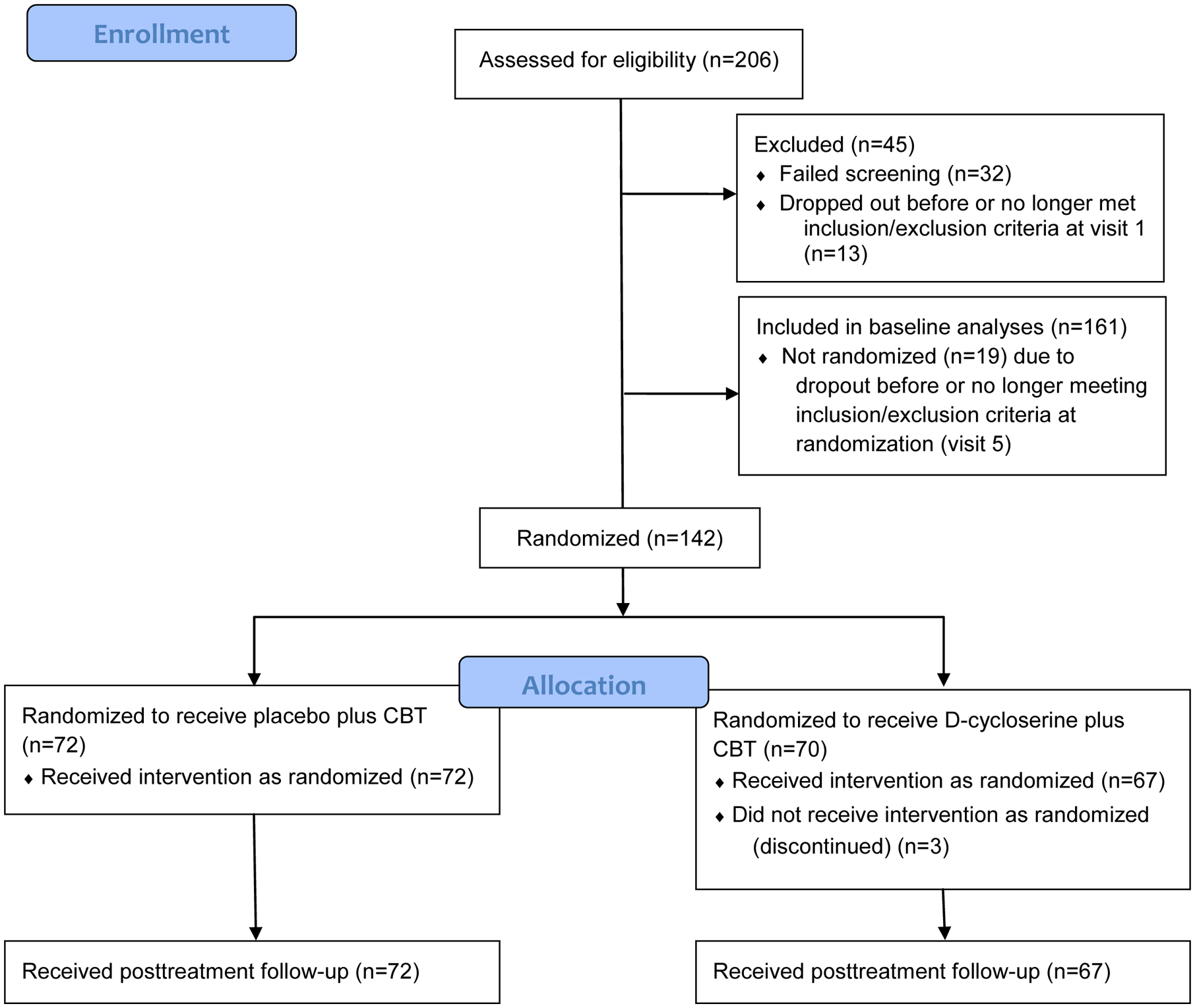

Two-hundred and six parent-child dyads consented to participate in the study, with 161 being eligible for pretreatment analyses. Of those, 142 were randomized to D-cycloserine or pill placebo plus ERP and were included in treatment outcome analyses with CY-BOCS as a dependent variable. Follow-up irritability measures were not completed with the first 29 children who were randomized; thus, analyses using the irritability measure as an outcome included 113 participants. No significant differences were found between participants with or without follow-up CBCL information in terms of baseline CY-BOCS, t(140) = 0.01, p = .99, or CBCL-Irritability, t(140) = −1.34, p = .18. See Figure 1 for the CONSORT diagram depicting enrollment, randomization, and study completion as it related to the original trial and the present analyses (i.e., 19 additional participants who were not randomized at visit 4 in the trial were included in analyses of baseline characteristics).

Figure 1.

Consort Flow Diagrama

a Adjusted from diagram presented in original trial to specify participants included in baseline analyses in this study

The majority of participants identified as White (91%). Approximately half identified as male (51%) and the mean age was 12.19 years-old. The range of responses to the CBCL-Irr questionnaire was 0–6 (M = 2.09; SD = 1.65). See Table 1 for a summary of demographics and Supplement 1 for a figure of the distribution of responses to the CBCL-Irritability subscale.

Table 1.

Demographics

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | Fatder’s highest education received | ||

| White | 145 (91%) | High school or less | 19 (12%) |

| African-American | 5 (3%) | Partial college, technical school, or associate’s degree | 40 (25%) |

| Asian | 3 (2%) | Bachelor’s degree | 53 (33%) |

| Otder | 5 (3%) | Graduate training | 45 (28) |

| Hispanic or Latino Etdnicity | 22 (13%) | Motder’s highest education received | |

| Male gender | 82 (51%) | High school or less | 16 (10%) |

| Comorbid diagnoses | Partial college, technical school, or associate’s degree | 38 (24%) | |

| Major depressive disorder | 17 (11%) | Bachelor’s degree | 66 (41%) |

| Panic disorder | 2 (1%) | Graduate training | 40 (25%) |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 9 (6%) | ||

| Specific phobia | 16 (10%) | ||

| Social anxiety disorder | 20 (12%) | ||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 36 (22%) | ||

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 29 (18%) | ||

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 16 (10%) | ||

| Chronic tic disorder | 7 (4%) | ||

| M (SD) | |||

| Age | 12.19 (3.08) |

What clinical characteristics are associated with irritability in youth with OCD?

Twenty-two percent of the sample exhibited elevated irritability. CBCL-Irritability was significantly and positively correlated with the CDRS, the CBCL-Defiance, the FAS, the CIS-parent and child report, and the COIS-parent report scales. No other significant associations were found. See Table 2 for a summary of correlation coefficients between the CBCL-Irritability subscale and other clinical variables.

Table 2.

Correlations between pretreatment CBCL-Irritability and other clinical variables

| CBCL-Irritability | |

|---|---|

| Psychiatric symptoms | |

| CDRS | .25* |

| CBCL-Defiance | .60** |

| MASC | .07 |

| OCD characteristics | |

| CY-BOCS | .07 |

| OBQ-CV: Perfectionism/Certainty | <−.01 |

| OBQ-CV: Responsibility/Threat | −.17 |

| OBQ-CV: Importance/Control | −.05 |

| CY-BOCS: Harm | −.05 |

| CYBOCS: Symmetry | .06 |

| CY-BOCS: Contamination | .02 |

| CY-BOCS: Sexual/Religious | −.02 |

| Individual and family functioning | |

| FAS | .23* |

| CIS-Parent | .56** |

| CIS-Child | .25* |

| COIS-Parent | .39** |

| COIS-Child | .20 |

p < .01;

p<.001

Note: CBCL=Child Behavior Checklist; CDRS: Children’s Depression Rating Scale; CIS: Columbia Impairment Scale; COIS: Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale; CY-BOCS: Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; FAS: Family Accommodation Scale; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder

In a multivariate linear regression including CBCL-Defiance, CDRS, FAS, and CIS-Parent Report, the variables together were found to account for 43% of the variance in CBCL-Irritability (only one functional impairment variable, the CIS-Parent Report, was included to reduce multicollinearity among functional impairment variables). CBCL-Irritability was significantly associated with the CBCL-Defiance, β = .40, p < .001, and the CIS-Parent Report, β = .38, p < .001, whereas it was not significantly associated with the CDRS, β = −.065, p = .40, and the FAS, β = −.032, p = .66, in the multivariate analysis.

Is irritability a predictor or moderator of treatment outcome?

Adding time to a null model predicting CY-BOCS scores significantly improved the fit of the model, χ2 (2) = 905.02, p < .001, with considerable reductions in AIC and BIC. There were significant fixed and random effects of time in this model, b = −1.15, p < .001, and b = 0.26, p < .001, respectively. The following nested model included Time*Condition, Time*CBCL-Irritability baseline scores, and Time*Condition*CBCL-Irritability baseline scores. The addition of these independent variables did not significantly improve the fit of the model, χ2 (3) = 5.01, p = .17, with increases in AIC and BIC. Accordingly, their fixed effects were nonsignificant, Time*Condition: b = .060, p = .71; Time*CBCL-Irritability baseline: b = .15, p = .11; time*Condition*CBCL-Irritability baseline: b = −.063, p = .30. Fixed and random effects of time remained significant in this model, b = −1.36, p < .001, and b = 0.25, p < .001, respectively, reflecting significant improvement in obsessive-compulsive symptoms across treatment with significant variability in the extent to which symptoms reduced. Please see the table in Supplement 2 for a summary of model parameters.

Does irritability improve following ERP?

It was estimated that 54% (n = 49/91) of the sample with any pretreatment irritability (i.e., CBCL-Irritability ≥ 1) experienced clinically significant change (Jacobsen & Truax, 1991). Mean level change among these youth was 0.71 points on the 0–6 CBCL-Irritability scale (M-pre: 2.68, M-post: 1.97). Among those with elevated pretreatment irritability (I.e., CBCL-Irritability ≥ 4), 64% (n = 17/26) were estimated to experience clinically significance change. Among these youth, scores declined by an average of 1.54 points on the 0–6 CBCL-Irritability scale (M-pre: 4.65, M-post: 3.11).

Accordingly, there was a significant linear effect of time on CBCL-Irritability in the MLM, b = −.047, p < .001 and including time in the MLM significantly improved on the null model, χ2 (2) = 23.48, p < .001, along with reductions in AIC and BIC. Adding the quadratic effect of session and time*treatment condition did not significantly improve the fit of the model and were not significant predictors of CBCL-Irritability. Adding the model with child-level slopes in associated clinical variables (CY-BOCS, CIS-P, CDRS, and FAS), however, significantly improved the fit of the model, χ2 (4) = 135.29, p < .001, along with reductions in AIC and BIC. Of those variables, the CIS-P*time interaction was the only significant predictor of CBCL-Irritability, such that reduced impairment across the trial was associated with reduced irritability. Please see Supplement 3 for a table with a summary of model parameters.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to investigate irritability in the clinical presentation and treatment of youth with OCD. Results replicate the broader literature (e.g., Brandes et al., 2019; Copeland et al., 2013; Evans et al., 2019; Shimshoni et al., 2020), finding that irritability was significantly associated with greater functional impairment, depressive symptoms, and defiant behavior, and extend these findings to youth with OCD. It was also found that families accommodated obsessive-compulsive symptoms to a greater degree among youth who were more irritable. Counter to hypotheses, however, irritability was not associated with anxiety, OCD severity, perfectionism and a need for certainty, exaggerated threat estimation or responsibility for harm, or treatment outcome. Finally, it was found that over half of youth with any pretreatment irritability experienced clinically significant improvements in irritability, providing some potential support for exposure-based therapy for irritability. The administration of D-cycloserine prior to exposure sessions was not significantly associated with irritability reduction relative to placebo.

Irritability has been strongly associated with negative affect and psychopathology (Beauchaine & Tackett, 2020; Brandes et al., 2019), which was consistent in this study of children with OCD. Specifically, more irritable youth with OCD also had higher reports of depression and defiance, two clinical syndromes that have been particularly strongly associated with irritability (Copeland et al., 2013). The literature linking depressive and defiant symptoms with irritability is vast, and it is likely that irritability reflects a broader genetic and temperamental predisposition to negative affect, emotion regulation difficulties, and psychopathology, which may account for its link with other diagnoses (Beauchaine & Tackett, 2020; Brandes et al., 2019). Results suggest particularly robust relationships between irritability and defiant behavior, as bivariate relationships were particularly strong between these variables, and they remained significant while controlling for other variables in a multivariate analysis. This pattern is consistent with the notion that although irritability is an independent affective dimension within the oppositional defiant disorder syndrome, it is still highly related to defiant behavior and other externalizing problems (Burke et al., 2014; Evans et al., 2019).

Accordingly, findings also highlighted a strong, consistent relationship between irritability and both overall and OCD-specific impairment. Functional impairment remained strongly associated with irritability even when controlling for defiance, depression, and family accommodation, underscoring the impact of irritability on children’s overall daily functioning. Further, parent-rated improvements in overall functional impairment was the only variable significantly associated with improvements in irritability. The direction of this relationship is not clear based on this study, but given the documented relationship between irritability and impairment (Copeland et al., 2013; Shimshoni et al., 2020), it is likely that as youth became less irritable during treatment, the functional impacts of irritability, such as poor school performance, family conflict, and peer relationship problems also improved. Alternatively, it is possible that as OCD symptoms improved, functioning also improved, which contributed to a less irritable overall mood (though it is worth noting stronger relationships noted in this study between irritability and overall functional impairment relative to OCD-related functional impairment). It is also likely that irritability and impairment were related bidirectionally in this sample. Overall, these findings underscore the importance of considering irritability when assessing overall disability in pediatric OCD.

A novel finding from this study was the link between irritability and family accommodation. This follows previous literature that has identified oppositional behavior, both broadly assessed and specific to OCD, as highly associated with family accommodation of symptoms (Lebowitz, Storch, MacLeod, & Leckman, 2015; Wu et al., 2019). Parents are likely more hesitant to resist accommodation, even if they are aware it is in the best long-term interest of their child, if it produces tantrums or aggressive outbursts, which has in turn been linked to greater symptom severity and OCD impairment (Lebowitz et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2019). While it is widely accepted that effective OCD treatment for children and adolescents should always incorporate caregivers to some degree, it is particularly critical in families with greater conflict and accommodation (Peris, Rozenman, Sugar, McCracken, & Piacentini, 2017), which is likely to be the case among irritable youth.

Findings contrast prior research identifying positive associations between anxiety and irritability, and failed to support hypotheses related to OCD severity and irritability. Krebs and colleagues (2013) found a similar pattern of results; that temper outbursts were positively related to depressive symptoms but not OCD severity in their sample of children with OCD. They proposed that beyond having clinically significant OCD, incremental increases in OCD severity do not appear to result in more tantrums, which our data further support when assessing an irritable mood more broadly. Future studies may benefit from comparing irritability among youth with OCD, youth with other psychiatric disorders, as well as healthy controls to further test that hypothesis. Multi-informant assessments of irritability with a wider range of responses may have also better elucidated relationships between irritability and anxiety/OCD (e.g., Stringaris et al., 2012). This approach may also better estimate the prevalence of elevated irritability in youth with OCD; this study estimated that 22% experience “elevated” irritability, which was lower than expected based on prior studies (Krebs et al., 2013; Shimshoni et al., 2020; Storch et al., 2012).

It was surprising that beliefs related to a responsibility to prevent harm, inflated threat perceptions, and intolerance of uncertainty/perfectionism were not associated irritability given research linking irritability with sensitive threat responding in lab-based paradigms (Salum et al., 2017) and recent survey research finding a link between irritability and intolerance of uncertainty (Evans, Blossom, & Fite, 2020). Future work may seek to develop questionnaires that assess beliefs and behaviors that are more reliably associated with clinical presentations of irritability in addition to lab-based behavioral investigations, adding to an understanding of irritability along multiple levels of analysis.

Given considerable research that has pointed to greater psychiatric chronicity and impairment among irritable youth, one promising finding was that more irritable youth did not experience poorer treatment outcomes. It is worth noting that this trial followed a family-based CBT treatment, and thus parental responses to irritable behaviors were often addressed during therapy through in-session practice as well as preparation for exposure homework, which may have been particularly helpful for irritable youth relative to a more child-focused protocol. Future research may consider investigating whether irritability is a moderator of individual vs. family-based CBT to more definitively determine whether caregiver involvement is particularly important in the treatment of irritable youth with OCD or anxiety disorders.

The finding that over half of youth with any baseline irritability experienced clinically significant improvements in irritability, along with 64% of youth with elevated pretreatment irritability, suggest promise for the exposure-based treatment of irritability. To the extent that irritable behaviors (e.g., tantrums) may be aggressive responses to distorted threat expectancies, it is likely that participating in repeated exposure helped facilitate extinction learning among youth with OCD, in turn producing fewer irritable responses (Kircanski et al., 2019). It is certainly the case that exposure to obsession triggers do elicit irritable reactions among some children (Lebowitz et al., 2015). Engaging in irritability exposures may have provided youth with opportunities to practice emotion regulation strategies that could have also led to less parent-reported irritability through treatment (Kircanski et al., 2019). That said, reductions in irritability were not found to correspond with OCD symptom reduction, and were found to decline at a consistent rate across therapy, rather than to a greater degree after the initiation of exposure. Further, conclusions about the effectiveness of exposure-based therapy for irritability are limited by the absence of a control condition or a protocol that explicitly targeted irritability. For these reasons, while we hypothesize that corrective learning and emotion regulation through exposure sessions were central in producing improvement in irritability, it is possible that irritability reduced due to other reasons such as having a supportive therapeutic relationship or regression to the mean among youth with more elevated scores. Future research should continue to investigate caregiver-involved, exposure-based therapy for irritability, and also assess whether exposure is effective when targeting aggressive reactions among individuals with OCD or anxiety disorders.

It is worth noting that improvement in irritability was not moderated by whether youth took D-cycloserine or placebo, suggesting that this agent may not be an enhancer of irritability improvement in exposure-based therapy. This finding follows the null results from the original trial (Storch et al., 2016) and echoes the relatively small effect sizes that have been found for D-cycloserine as an enhancer of anxiety or fear outcomes following exposure-based therapy (Mataix-Cols et al., 2017).

This study had several limitations. First, the sample consisted of largely White, educated families, and thus conclusions are restricted to this population; irritability and OCD should continue to be studied in more culturally diverse samples. Multi-method (e.g., interview-rated, behavioral), multi-informant assessments of irritability and other study variables would have also better elucidated the nature of irritability in OCD, as well as its treatment implications. Notably, the strongest relationships observed with the CBCL-Irritability scale were with other parent-report measures (parent-reported impairment, defiance); thus, it will be important for future work to investigate multiple-informant assessments of all of these variables. Conclusions regarding the potential of exposure-based therapy for irritability are also limited, as clinicians designed exposures to address obsessive-compulsive symptoms rather than irritability; future work should continue to study exposure therapy specifically for irritability triggers. Because our study underscores irritability as an important correlate of a severe, comorbid presentation (e.g., with depressive symptoms, externalizing behaviors, psychiatric impairment), it may be important for future latent variable analyses (e.g., cluster analysis) to evaluate OCD subtypes that incorporate measures of comorbidity and disability.

Conclusions

This study was the first to investigate irritability among children and adolescents with OCD. In line with the broader literature, irritable youth with OCD appear to experience more severe depressive symptoms, defiant behaviors, and functional impairment, supporting irritability as a marker of greater negative affectivity and psychopathology. Families also described more accommodation among irritable youth, highlighting the importance of caregiver involvement in CBT for this population. Finally, the majority of youth with pretreatment irritability experienced clinically significant reductions in irritable symptoms, providing some promising support for family-based, exposure-focused CBT for irritability in children and adolescents.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Irritability was directly associated with depression, defiance, and impairment

Irritability was significantly and positively associated with family accommodation

Irritability was not significantly associated with OCD severity or anxiety

Clinically significant improvement in irritability was found in 54% of youth

Improvement in irritability was not related to OCD symptom reduction

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals to the original trial: Susan Sprich, PhD, Aude Henin, PhD, Jamie Micco, PhD, Joseph McGuire, PhD, P Jane Mutch, PhD, Monica Wu, PhD, Robert Selles, Ph.D., Adam B Lewin, PhD, ABPP, Allison Kennel, ARNP, Nicole McBride, PhD, Alyssa Faro, PhD, Kelsey Ramsay, Ashley Brown, Andrew MIttelman, Abigail Stark, PhD, Allison Cooperman, Angelina Gomez, Chelsea Ale, PhD, Kathleen Trainor, PhD, Cary Jordan, PhD, Christine Cooper-Vince, PhD, Anne Chosak, PhD, Noah Berman, PhD, Marco Grados, MD, Gary Geffken, PhD, Rebecca Betensky, PhD, Barbara Coffey, MD, Martin Franklin, PhD, Jennifer Britton, PhD, David Greenblatt, MD, and David Pauls, PhD.

Funding:

This study was funded by grants 1R01MH093381 (Dr. Storch) and 5R01MH093402 (Dr. Geller) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The NIMH had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of this report, or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

clinicaltrials.govIdentifier:NCT00864123

References

- Abramowitz JS (2018). Presidential address: are the obsessive-compulsive related disorders related to obsessive-compulsive disorder? A critical look at DSM-5’s new category. Behavior Therapy, 49(1), 1–11. 10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: Aseba. [Google Scholar]

- Ale CM, McCarthy DM, Rothschild LM, & Whiteside SP (2015). Components of cognitive behavioral therapy related to outcome in childhood anxiety disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(3), 240–251. 10.1007/s10567-015-0184-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althoff RR, Kuny-Slock AV, Verhulst FC, Hudziak JJ, & van der Ende J (2014). Classes of oppositional-defiant behavior: Concurrent and predictive validity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(10), 1162–1171. 10.1111/jcpp.12233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, & Choate ML (2016). Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders–republished article. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 838–853. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, & Tackett JL (2020). Irritability as a transdiagnostic vulnerability trait: Current issues and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 51(2), 350–364. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Shaffer D, Fisher P, & Gould MS (1993). The Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS): pilot findings on a measure of global impairment for children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 3(3), 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes CM, Herzhoff K, Smack AJ, & Tackett JL (2019). The p factor and the n factor: Associations between the general factors of psychopathology and neuroticism in children. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1266–1284. 10.1177/2167702619859332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Kircanski K, Stringaris A, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2017). Irritability in youths: a translational model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(6), 520–532. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Boylan K, Rowe R, Duku E, Stepp SD, Hipwell AE, & Waldman ID (2014). Identifying the irritability dimension of ODD: Application of a modified bifactor model across five large community samples of children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(4), 841. 10.1037/a0037898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvocoressi L, Mazure CM, Kasl SV, Skolnick J, Fisk D, Vegso SJ, Van Noppen BL, & Price LH (1999). Family accommodation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms: instrument development and assessment of family behavior. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(10), 636–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles ME, Wolters LH, Sochting I, De Haan E, Pietrefesa AS, & Whiteside SP (2010). Development and initial validation of the obsessive belief questionnaire-child version (OBQ-CV). Depression and Anxiety, 27(10), 982–991. 10.1002/da.20702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ, & Egger H (2013). Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of DSM-5 proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(2), 173–179. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornacchio D, Crum KI, Coxe S, Pincus DB, & Comer JS (2016). Irritability and severity of anxious symptomatology among youth with anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(1), 54–61. 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant AR, & Levy UH (2014). D-Cycloserine. In Stolerman IP & Price LH. Encylopedia of Psychopharmacology. Springer, Berline, Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-642-27772-6_7018-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SC, Blossom JB, & Fite PJ (2020). Exploring longitudinal mechanisms of irritability in children: implications for cognitive-behavioral intervention. Behavior Therapy, 51(2), 238–252. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SC, Bonadio FT, Bearman SK, Ugueto AM, Chorpita BF, & Weisz JR (2019). Assessing the irritable and defiant dimensions of youth oppositional behavior using CBCL and YSR items. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–16. 10.1080/15374416.2019.1622119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SC, Weisz JR, Carvalho AC, Garibaldi PM, Bearman SK, & Chorpita BF (2020). Effects of standard and modular psychotherapies in the treatment of youth with severe irritability. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(3), 255. 10.1037/ccp0000456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallop R, & Tasca GA (2009). Multilevel modeling of longitudinal data for psychotherapy researchers: II. The complexities. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 438–452. 10.1080/10503300902849475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George D, & Mallery P (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step. A simple study guide and reference (10). GEN, Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Caelian CF, Flett GL, Sherry SB, Collins L, & Flynn CA (2002). Perfectionism in children: Associations with depression, anxiety, and anger. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(6), 1049–1061. 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00109-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hezel DM, & McNally RJ (2016). A theoretical review of cognitive biases and deficits in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Biological Psychology, 121 (Part B), 221–232. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, & Truax P (1992). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Ryan ND, & Rao U (2000). K-SADS-PL. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(10), 1208. 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircanski K, Craske MG, Averbeck BB, Pine DS, Leibenluft E, & Brotman MA (2019). Exposure therapy for pediatric irritability: Theory and potential mechanisms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 118, 141–149. 10.1016/j.brat.2019.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs G, Bolhuis K, Heyman I, Mataix-Cols D, Turner C, & Stringaris A (2013). Temper outbursts in paediatric-obsessive compulsive disorder and their association with depressed mood and treatment outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(3), 313–322. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02605.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz ER, Storch EA, MacLeod J, & Leckman JF (2015). Clinical and family correlates of coercive–disruptive behavior in children and adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(9), 2589–2597. 10.1007/s10826-014-0061-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limburg K, Watson HJ, Hagger MS, & Egan SJ (2017). The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(10), 1301–1326. 10.1002/jclp.22435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R, & Rubin D (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data (second edition). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, & Conners CK (1997). The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 554–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, De La Cruz LF, Monzani B, Rosenfield D, Andersson E, Pérez-Vigil A, … & Farrell LJ (2017). D-cycloserine augmentation of exposure-based cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, and posttraumatic stress disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. JAMA psychiatry, 74(5), 501–510. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty R (2016). The fight-or-flight response: A cornerstone of stress research. In Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nikoo M, Radnia H, Farokhnia M, Mohammadi MR, & Akhondzadeh S (2015). N-acetylcysteine as an adjunctive therapy to risperidone for treatment of irritability in autism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Clinical neuropharmacology, 38(1), 11–17. 10.1097/WNF.0000000000000063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, & Paulus DJ (2017). Transdiagnostic models of anxiety disorder: Theoretical and empirical underpinnings. Clinical Psychology Review, 56, 122–137. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Pediatric O.C.D. Treatment Study Team (2004). Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 292(16), 1969. 10.1001/jama.292.16.1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Rozenman MS, Sugar CA, McCracken JT, & Piacentini J (2017). Targeted family intervention for complex cases of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(12), 1034–1042. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Peris TS, Bergman RL, Chang S, & Jaffer M (2007). Functional impairment in childhood OCD: Development and psychometrics properties of the child obsessive-compulsive impact scale-revised (COIS-R). Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 36(4), 645–653. 10.1080/15374410701662790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, & Mokros HB (1996). Children’s depression rating scale, revised (CDRS-R). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Reed GM, First MB, Kogan CS, Hyman SE, Gureje O, Gaebel W, … & Claudino A (2019). Innovations and changes in the ICD-11 classification of mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 3–19. 10.1002/wps.20611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, Lopes V, & Klein RG (2014). Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: a new diagnostic approach to chronic irritability in youth. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(9), 918–924. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salum GA, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Stringaris A, Gadelha A, Pan PM, Rohde LA, Polanczyk GV, Manfro GG, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2017). Association between irritability and bias in attention orienting to threat in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(5), 595–602. 10.1111/jcpp.12659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J, Verhulst B, Copeland W, Althoff RR, Lichtenstein P, & Roberson-Nay R (2015). A genetically informed study of the longitudinal relation between irritability and anxious/depressed symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 54(5), 377–384. 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, Cicchetti D, & Leckman JF (1997). Children’s Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: reliability and validity. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 36(6), 844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimshoni Y, Lebowitz ER, Brotman MA, Pine DS, Leibenluft E, & Silverman WK (2020). Anxious-Irritable Children: A distinct subtype of childhood anxiety? Behavior Therapy, 51(2), 211–222. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, & Willett JB (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford university press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard J, Stringaris A, Brotman MA, Montville D, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2014). Irritability in child and adolescent anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 31(7), 566–573. 10.1002/da.22151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Jones AM, Lack CW, Ale CM, Sulkowski ML, Lewin AB, De Nadai AS, & Murphy TK (2012). Rage attacks in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: phenomenology and clinical correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(6), 582–592. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Larson MJ, Bloss CS, Geffken GR, Jacob ML, Murphy TK, & Goodman WK (2008a). Symptom dimensions and cognitive-behavioural therapy outcome for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117(1), 67–75. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Larson MJ, Geffken GR, Lehmkuhl HD, Jacob ML, Murphy TK, & Goodman WK (2008b). Impact of comorbidity on cognitive-behavioral therapy response in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 583–592. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816774b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Wilhelm S, Sprich S, Henin A, Micco J, Small BJ, McGuire J, Mutch PJ, Lewin AB, Murphy TK, & Geller DA (2016). Efficacy of augmentation of cognitive behavior therapy with weight-adjusted d-cycloserine vs placebo in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 73(8), 779–788. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Baroni A, Haimm C, Brotman M, Lowe CH, Myers F, Rustgi E, Wheeler W, Kayser R, Towbin K, & Leibenluft E (2010). Pediatric bipolar disorder versus severe mood dysregulation: risk for manic episodes on follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(4), 397–405. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2009). Adult outcomes of youth irritability: a 20-year prospective community-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(9), 1048–1054. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R, Ferdinando S, Razdan V, Muhrer E, Leibenluft E, & Brotman MA (2012). The Affective Reactivity Index: a concise irritability scale for clinical and research settings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(11), 1109–1117. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02561.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Smith SD, McCauley SA, Ibrahim K, & Piasecka JB (2016). Behavioral interventions for anger, irritability, and aggression in children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(1), 58–64. 10.1089/cap.2015.0120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Worhunsky P, & Maltby N (2006). Are “obsessive” beliefs specific to OCD?: A comparison across anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(4), 469–480. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng WL, Moroney E, Machlin L, Roberson-Nay R, Hettema JM, Carney D, Stoddard J, Towbin KA, Pine DS, Leibenluft E, & Brotman MA (2017). Test-retest reliability and validity of a frustration paradigm and irritability measures. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 38–45. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, & Craske MG (2016). Towards a cognitive-learning formulation of youth anxiety: A narrative review of theory and evidence and implications for treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 50, 50–66. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2019). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 11th ed (ICD-11). https://icd.who.int/

- Wu MS, Geller DA, Schneider SC, Small BJ, Murphy TK, Wilhelm S, & Storch EA (2019). Comorbid psychopathology and the clinical profile of family accommodation in pediatric OCD. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 50(5), 717–726. 10.1007/s10578-019-00876-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.