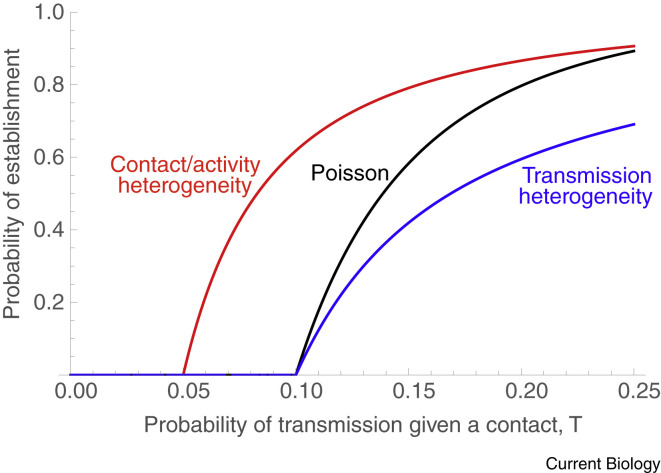

Figure 1.

The role of heterogeneity in the probability that a variant establishes within a population.

Illustrated here is a predominantly susceptible population, with an average number of ten contacts per case and no competition for susceptible hosts between the variant and non-variant. If the number of contacts per individual is Poisson distributed and there is a constant chance of infection per contact, the probability of establishment rises with the chance of infection per contact as shown by the black curve. Here, variants are not expected to persist unless the transmission probability is above 10%, as only then are cases expected to give rise to at least one new case (Rt > 1). If cases vary in their infectiousness, then variants are less likely to establish because more cases fail to have any onward transmission (blue curve, where we assume that half of the cases are three times as infective as the other half). If, however, there is variability in contact number or activity level, variants are more likely to establish because individuals with more contacts are more likely to get infected and then more likely to pass on the variant (red curve, assuming the contact distribution is negative binomial with a dispersion parameter of k = 3). Because the disease spreads more easily among the subset of active people, heterogeneity in contacts also reduces the critical transmission probability above which establishment is possible (red curve rises above zero earlier, causing Rt > 1). (Based on methods in reference75.)