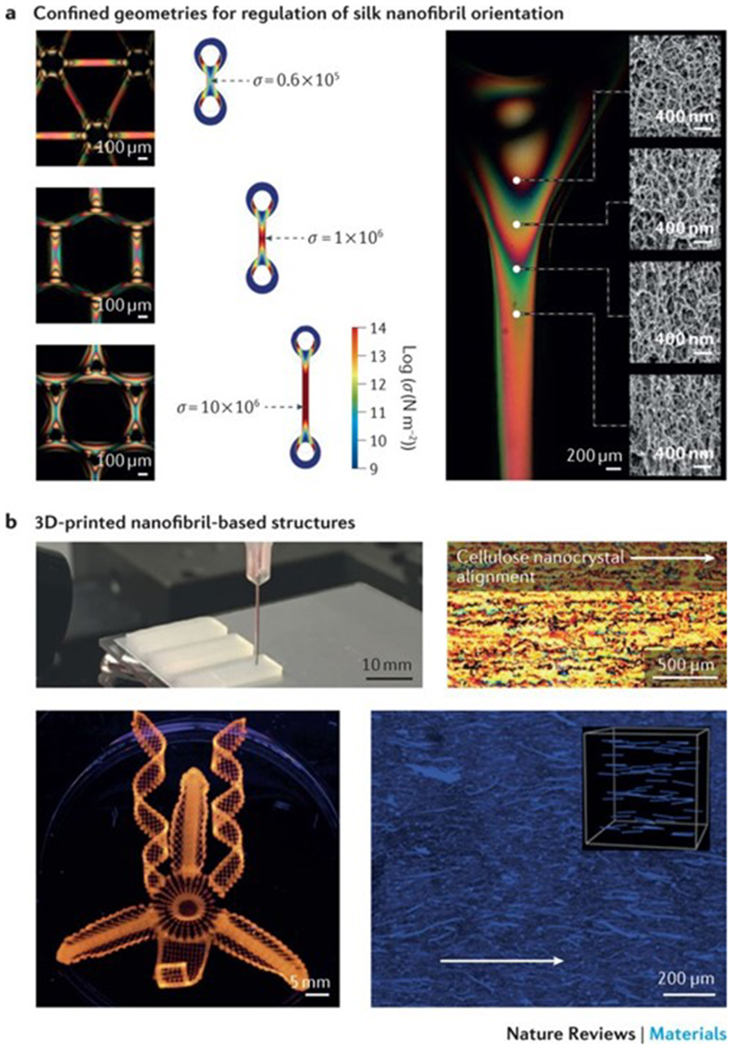

Figure 4|. Artificial spinning of biopolymer nanofibrils.

a | The stress–strain curves of biopolymer nanofibril fibres illustrate the differences in the stress–strain behaviour of fibres produced by wet spinning (WS), dry spinning (DS) or microfluidic spinning (MS). b | These differences are also reflected in the relationship between the specific elastic modulus and the specific strength of the fibres. c | The orientation index (or order parameter) of the fibrillar structures has an effect on the strength and elastic modulus of the fibres. d | Microfluidic spinning can be applied to regulate the orientation of biopolymer nanofibrils. The nanofibrils in the focused flow are illustrated as rods (the fibril length in relation to the channel width is exaggerated by a factor of approximately 300). The diffusion of Na+ (blue) is added in the form of NaCl in the focusing liquid. In a microfluidic spinning device, the nanofibrils in the spinning dope are free to rotate owing to strong electrostatic repulsion, and they align towards the accelerating flow direction. The hydrodynamical, molecular and electrochemical processes involve Brownian diffusion (dashed arrows) and hydrodynamically induced alignment (solid arrows). The scanning electron microscopy image shows the surface of a cellulose nanofibril-based regenerated fibre. BNF, biopolymer nanofibril; ChNF, chitin nanofibril; CNF, cellulose nanofibril; SNF, silk nanofibril. The stress–strain curves in part a are drawn using the stress–strain curves data from REFS 27,30,33–36. Parts b and c use data from REFS 27,30,33–36. Panel d is reproduced and adapted from REFS 35, CC-BY-3.0; and adpated from REF. 36, CC-BY-4.0.