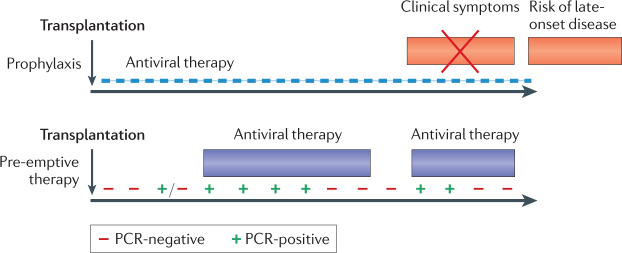

Fig. 5. Two distinct strategies used to reduce human cytomegalovirus disease in allograft recipients.

In the case of prophylaxis (upper panel), an antiviral drug is given from the time of transplantation (as soon as the patient can tolerate oral medication) for a fixed period of time, with clinical trials for solid organ transplantation (SOT) supporting durations of either 100 or 200 days59,124. This strategy is effective in preventing end organ disease (EOD), but patients are at risk once again after prophylaxis is stopped, including with strains of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) resistant to the drug used for prophylaxis (late-onset disease)125. In the case of pre-emptive therapy (PET) (lower panel), patients are monitored frequently to determine whether HCMV DNA is detectable by PCR. Individuals with low viral loads continue to be monitored, but those with a viral load above a defined threshold are given antiviral therapy until two consecutive blood tests can no longer detect HCMV DNA. Patients continue to be monitored and may require a subsequent episode of PET. Humoral and cell-mediated responses are superior in SOT managed using PET and late-onset disease is uncommon58,62. For haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT), valganciclovir prophylaxis cannot be used because of bone marrow toxicity of the drug. Letermovir is safe enough to be used for prophylaxis79 and is combined with PET. If the individual fails to respond to treatment (that is, the viral load does not show at least a one-log reduction over 2 weeks), refractory HCMV infection is diagnosed. This may be due to poor host responses and/or the selection of strains resistant to the antiviral drug being administered. At present, foscarnet is commonly used to treat ganciclovir-resistant strains of HCMV, but has severe side effects. Phase II results for maribavir are encouraging126 with phase III randomized clinical trial (RCT) results expected in 2021.