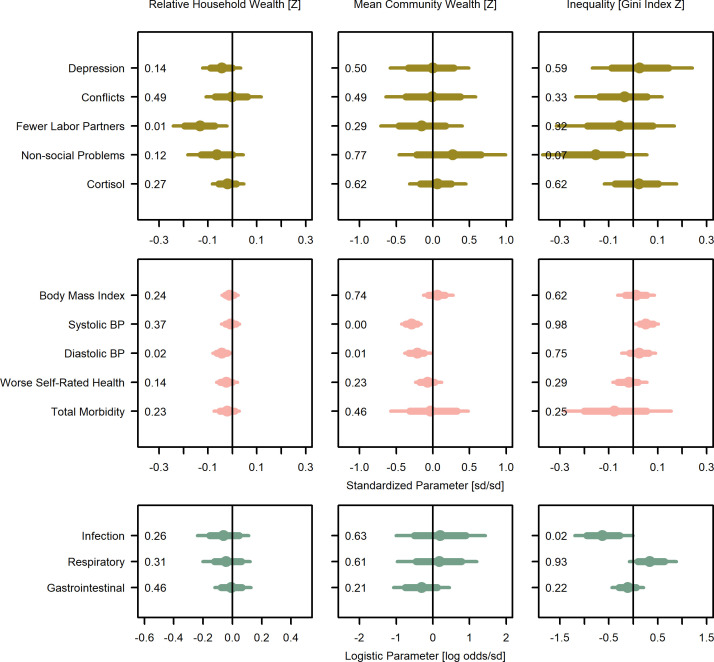

Figure 2. Wealth and inequality posterior parameter values for models with adults (>15 years).

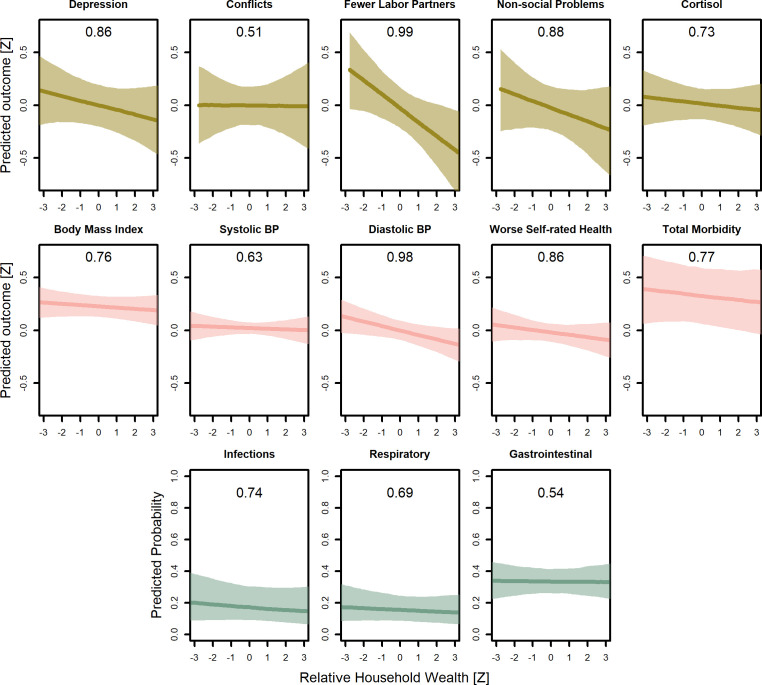

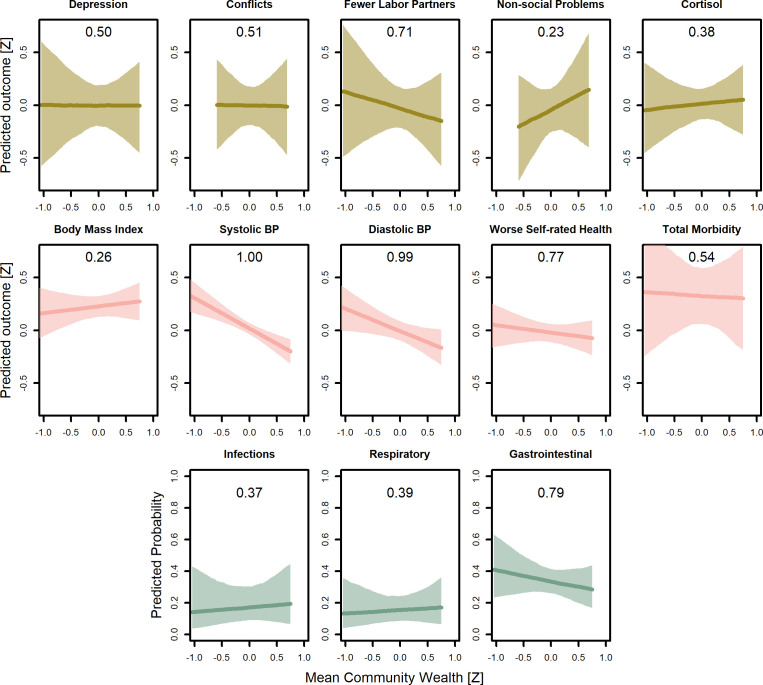

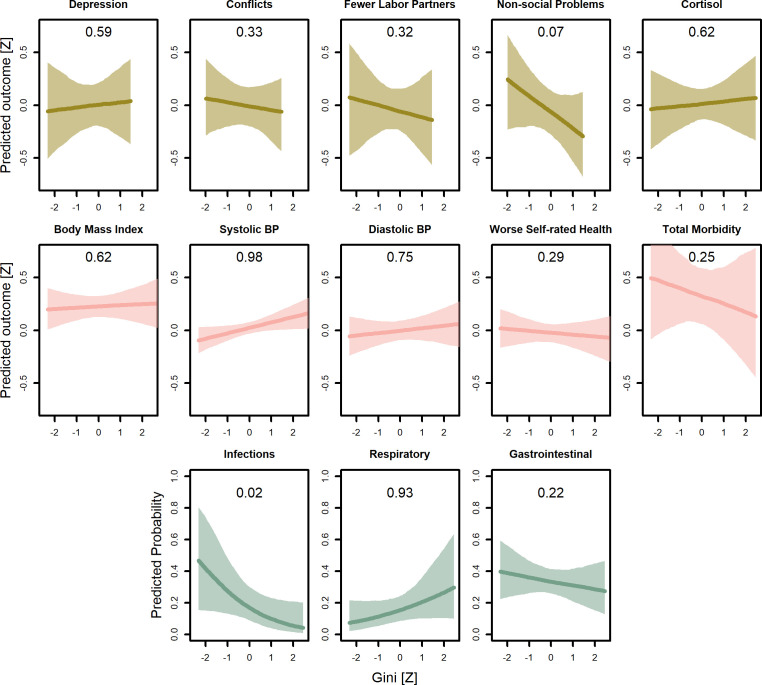

Points are posterior medians and lines are 75% (thick) and 95% (thin) highest posterior density intervals. Numbers in each panel represent the proportion of the posterior distribution that is greater than zero (P>0). All models control for age, sex, distance to market town, and community size. Rough categories of dependent variables (psychosocial, continuous health outcomes, and binary health outcomes) are distinguished by rows and colors. For the first two rows, the outcomes are expressed as Z-scores, the bottom row as log odds. See Figure 2—figure supplement 1, Figure 2—figure supplement 2, and Figure 2—figure supplement 3 for predicted associations of household wealth, community wealth, and wealth inequality, respectively.