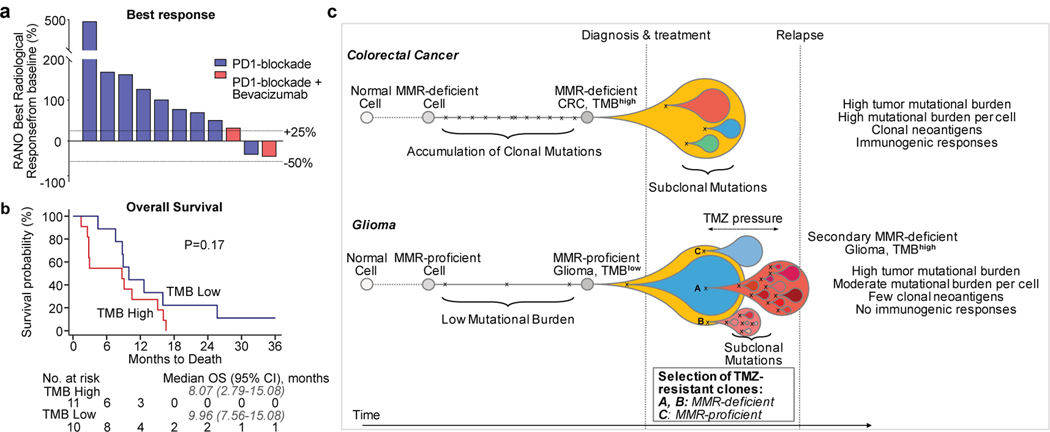

Figure 4. Treatment of Hypermutated Gliomas with PD-1 Blockade.

a, b, Best radiological response (a, measured as the best change in the sum of the products of perpendicular diameters of target lesions), and overall survival (b) of 11 patients with hypermutated and MMR-deficient gliomas who were treated with PD-1 blockade. A cohort of patients with non-hypermutated gliomas who were treated with PD-1 blockade is depicted as control (n = 10, best matches according to diagnosis, primary versus recurrent status, and prior treatments). Two-sided log-rank test. c, Proposed model explaining differential response to PD-1 blockade in MMR-deficient CRCs and gliomas. In CRCs (top), MMR deficiency is acquired early in pre-cancerous cells, creating mutations and indels at homopolymer regions. Over time, clonal neoantigens of both types emerge and strong immune infiltrates are seen at diagnosis. Treatment with anti-PD-1 results in expansion of T cells that recognize these clonal neoantigens and substantial antitumour responses. In gliomas (bottom), few mutations are acquired early during tumorigenesis in the majority of tumours. Temozolomide drives the expansion of cells with MMR deficiency and late accumulation of random temozolomide-induced mutations. Ineffective antitumour responses may result from poor neoantigen quality (high burden of missense mutations versus frameshift-producing indels) and high subclonality associated with an immunosuppressive microenvironment. In some tumours, MMR-proficient subclones that have acquired therapy resistance through other pathways can co-exist with MMR-deficient subclones, giving rise to a mixed phenotype.