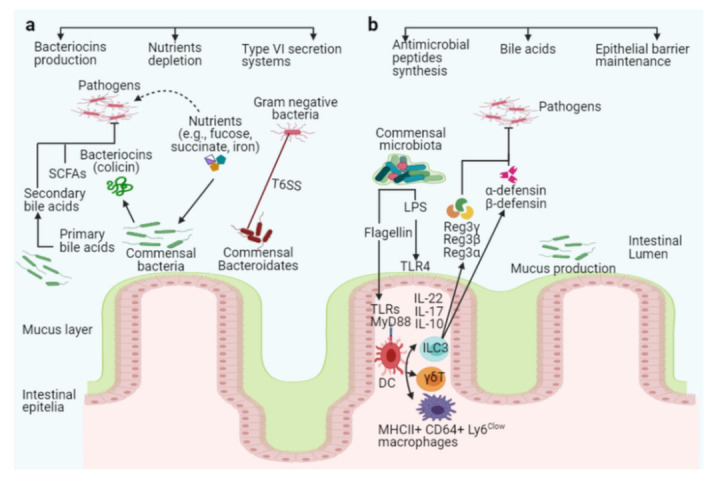

Figure 2.

The intestinal microbiota acts as a barrier against enteric pathogens via direct and indirect colonization resistance mechanisms. Direct colonization resistance mechanisms (a): Several commensal Bacteroidetes prevent pathogens from colonizing the intestinal mucosa, and the commensal E. coli Nissle strain consumes nutrients, limiting nutrients availability to specific pathogens (pink color with flagella). The probiotic E. coli Nissle strain can also absorb iron, limiting its availability to the pathogen S. Typhimurium. Commensal bacteria secrete antimicrobial peptides, such as bacteriocins (colicin), SCFAs, and T6SS, to target and kill invading pathogens. Together with antimicrobial peptides, commensal bacteria produce enzymes that convert conjugated primary bile acids to secondary bile acids (toxic to invading pathogens). Indirect colonization resistance mechanisms (b): Surface antigens such as flagellin or LPS from commensals bacteria stimulate host innate immunity via TLRs and MyD88 on epithelial or dendritic cells (DCs). ILC3, γδT, and Th17 cells can be activated to produce interleukin IL-10, IL-17, and IL-22, which promotes secretion of the antimicrobial peptides Reg3γ, Reg3β, Reg3α, α-defensin, and β-defensin from epithelial cells to inhibit pathogen colonization in the intestines (pink color with flagella).