Abstract

Background

The impact of lockdown measures can be widespread, affecting both clinical and psychosocial aspects of health. This study aims to assess changes in health services access, self‐care, behavioural, and psychological impact of COVID‐19 and partial lockdown amongst diabetes patients in Singapore.

Methods

We conducted a cross‐sectional online survey amongst people with diabetes with the Diabetes Health Profile‐18 (DHP‐18). Hierarchical regression analyses were performed for each DHP‐18 subscale (Psychological Distress, Disinhibited Eating and Barriers to Activity) as dependent variables in separate models.

Results

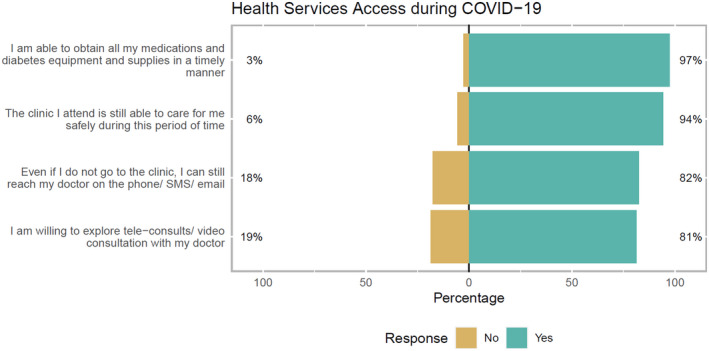

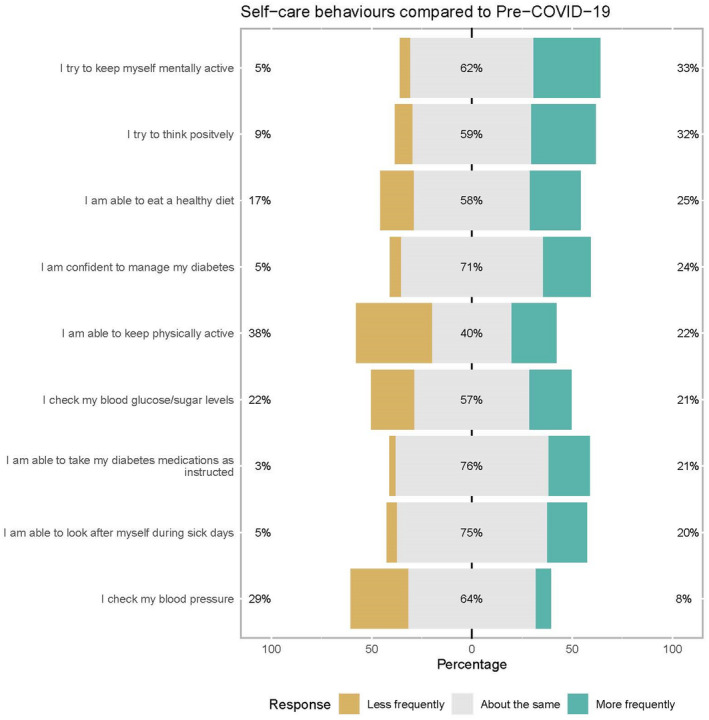

Among 301 respondents, 45.2% were women, 67.1% of Chinese ethnicity, 24.2% were aged 40 to 49 years, 68.4% have Type 2 diabetes and 42.2% on oral medications alone. During the pandemic and the lockdown, nearly all respondents were able to receive care safely from the clinics they attend (94%) and obtain their medications and diabetes equipment and supplies (97%) when needed. Respondents reported less frequent engagement in physical activity (38%), checking of blood pressure (29%) and blood glucose (22%). Previous diagnosis of mental health conditions (β = 9.33, P = .043), Type 1 diabetes (β = 12.92, P = .023), number of diabetes‐related comorbidities (β = 3.16, P = .007) and Indian ethnicity (β = 6.65, P = .034) were associated with higher psychological distress. Comorbidities were associated with higher disinhibited eating (β = 2.49, P = .014) while ability to reach their doctor despite not going to the clinic is negatively associated with psychological distress (β = −9.50 P = .002) and barriers to activity (β = −7.53, P = .007).

Conclusion

Health services access were minimally affected, but COVID‐19 and lockdown had mixed impacts on self‐care and management behaviours. Greater clinical care and attention should be provided to people with diabetes with multiple comorbidities and previous mental health disorders during the pandemic and lockdown.

What’s known

COVID‐19 and lockdown have a diverse impact on health services access, psychosocial well‐being and self‐management in people with diabetes, which needs to be contextualised to individual country responses and preparedness.

What’s new

In this Singapore‐based study, access to medications and supplies were minimally affected for people with diabetes.

People with diabetes with history of mental health conditions and multiple comorbidities, type 1 diabetes and Indian ethnicity are at higher risk of greater psychological distress.

Physical activity is one of the most impacted self‐care behaviours in the current pandemic while blood glucose monitoring and dietary management had mixed responses.

1. INTRODUCTION

The acute and long‐term consequences of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic and related public health measures such as mass quarantine with resultant social isolation on mental health are beginning to emerge. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 The pandemic and quarantine measures may have led to many losses including a loss of loved ones, employment, financial security, direct social contacts, educational opportunities, recreation and social support. A review of the psychological impact of quarantine demonstrated a high prevalence of psychological symptoms and emotional disturbance. 9 A few groups of vulnerable individuals for adverse psychosocial outcomes have been identified, in particular people who have contracted the disease, those who are at higher risk for contracting the disease and those with pre‐existing medical, psychiatric or substance use issues. 10

The impact of lockdown can be widespread, affecting both clinical and psychosocial aspects of health. Psychosocial well‐being of people with diabetes can be particularly affected because of COVID‐19‐specific worries as people with diabetes are considered at higher risk of more severe infection. 11 Adherence to medications and healthy behaviours was significantly reduced because of drastic changes in lifestyles brought about by lockdown measures. 12 , 13 In some instances, glycaemic control in people with Type 1 diabetes (T1DM) was affected because of difficulty in obtaining medical supplies 14 while in other instances, glycaemic control based on continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) metrics improved in people who had stopped working during the lockdown. 15 Others reported only minor changes brought on by COVID‐19 on T1DM and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) self‐care with the majority maintaining baseline physical activity and dietary habits. 16 Thus, the magnitude of the impact of this global pandemic must be contextualised to different government responses, health systems and population settings. Singapore's healthcare system adopts a mixed delivery model, with both public and private healthcare providers playing an important role. Public healthcare institutions (known as restructured hospitals) deliver ~80% of acute care while primary care is predominantly delivered by private providers. 17 Although there is no information on the proportion of people with diabetes in Singapore managed by public vs. private providers, it is likely that majority of people with diabetes, a chronic disease, is managed in the public sector because of the presence of subsidies for pharmacotherapeutic agents.

1.1. COVID‐19 response measures in Singapore

In Singapore, the “Disease Outbreak Response System Condition” (DORSCON), a four‐tier colour‐coded framework provides general guidance to mitigate the transmission and impact of infectious diseases. Following Singapore's first index case of COVID‐19 in January 2020, DORSCON risk assessment escalated from Yellow to Orange on 7 February 2020. 18 With rising numbers of positive COVID‐19 cases, a partial lockdown, termed “Circuit Breaker” began on 7 April 2020. 19 Several measures implemented during lockdown included restriction of movement and gatherings, stay‐home orders, home‐based learning for schools and closure of physical workplace premises, except for those providing essential services. 19 Use of face masks was made compulsory. 19 Within the healthcare sector, non‐essential clinic appointments and procedures were postponed or moved to a teleconsultation platform. Clinical appointments deemed essential were allowed to carry on with safe distancing measures, temperature screening and travel history declarations in place as precautionary measures to prevent the transmission of COVID‐19.

A phased approach was adopted in the gradual resumption of services and activity 20 as Singapore entered Phase 1 of gradual re‐opening on 1 June 2020. The public could leave home for essential activities, while seniors were encouraged to continue staying at home. Health and preventive health services resumed based on prioritisation by medical needs while medical services for stable conditions continued to be deferred. 21 Phase 2 (19 June 2020) enabled further resumption of most activities, subject to safe distancing principles and in groups not exceeding 5 persons. 22 At the time of writing, the country was still under Phase 2.

Diabetes, along with age, other medical comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity, chronic heart and lung disease, has been identified as a significant risk factor for severe COVID‐19 infection, including hospitalisation, ICU admissions and worse outcomes. 23 , 24 , 25 Apart from the direct impact of diabetes on COVID‐19 infection, the indirect risks of the pandemic and lockdown measures on people with diabetes include disruptions to follow‐up care, access to medications and supplies, as well as changes to routine diabetes self‐management strategies, particularly diet and physical activity. 26 This study, conducted during Phase 1 and 2 of gradual re‐opening, between June and October 2020, sought to firstly, assess changes in health services access and diabetes self‐care practices of people with diabetes during COVID‐19 and lockdown; and secondly, to analyse the relationship between sociodemographic factors, diabetes profile (medication status, diabetes type, duration and comorbidities) and previous diagnosis of mental health conditions on the well‐being of people with diabetes, using the Diabetes Health Profile‐18 (DHP‐18) questionnaire during COVID‐19 and lockdown, through an online survey.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

This study is a cross‐sectional survey of adults, aged 21 years and above, with diabetes, residing in Singapore. Patients were recruited by study team members from two public hospitals in Singapore or learnt about the survey via recruitment posters. The study was also publicised via a diabetes voluntary welfare organisation, electronic direct mailers and social media diabetes support groups. No personal identifiers were collected and the online survey was hosted on a government‐approved secured digital form. Ethical approval for the study and waiver of consent were obtained from our Institutional Review Board. Information regarding the study purpose, survey eligibility criteria, research team composition, contact information for queries/clarification as well as privacy and confidentiality information were listed at the front page of the survey. Participants would have to read them prior to starting the survey.

Participants were also informed that should they want an independent opinion to discuss problems and questions, obtain information and offer input on their rights as a research subject, they may contact the Ethics Committee secretariat with the contact number provided. Participants did not receive any inconvenience fee.

2.2. Measures and scales collected

Sociodemographic information was collected: age range, gender, ethnicity, marital status, educational qualification, and employment status. Current housing status, number of persons residing in the same household and monthly household income per household member 27 were surveyed.

Diabetes history including diabetes type, diabetes duration, current medications for diabetes, presence of diabetes‐related complications and comorbidities and prior diagnosis of mental health conditions and treatment were asked.

The usual site for follow‐up diabetes care (specialist outpatient clinics in public hospitals, private care providers, general practitioners and/or public primary care), frequency of visits per year prior to COVID‐19 and relative change in clinic visits (more frequently, less frequently or the same) following COVID‐19 and lockdown were documented.

Disruptions and barriers in accessing care as a result of COVID‐19 and lockdown were assessed with the following questions and dichotomous responses (yes/no) on whether patients: (a) perceive their clinics were still able to provide care safely, (b) can obtain advice from doctors through other means (phone, email, text‐messaging) and (c) can receive diabetes medications, equipment and supplies in a timely manner. In addition, patients’ willingness to explore telephone or video consultation with their doctor was examined.

We asked participants to compare diabetes self‐care behaviours during COVID‐19 period with before COVID‐19: the ability to keep mentally and physically active, eat a healthy diet, adhere to medications, monitor blood glucose (BG), blood pressure (BP) and confidence in diabetes self‐management (less frequently, about the same or more frequently).

2.2.1. Diabetes Health Profile‐18 (DHP‐18)

The DHP‐18 is an 18‐item scale which assesses psychosocial and behavioural impact of living with diabetes in three domains: psychological distress (six questions), barriers to activity (seven questions) and disinhibited eating (five questions). 28 Each item is measured on a 4‐point Likert scale, corresponding to a score of 0 to 3, with 0 indicating “no dysfunction.” The scores from questions under each subscale is aggregated and transformed to a 0 to 100 score, with higher scores representing greater levels of dysfunction. 29 The validity and reliability of DHP‐18 has been previously assessed amongst local T2DM patients, 30 and DHP‐18 has been used for assessing psychological distress. 31 , 32 Participants were asked to compare how they felt during the COVID‐19 pandemic and circuit breaker, as compared with before the pandemic.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis of the results was performed. Continuous variables were expressed as mean (µ) and standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented in counts and proportion. Hierarchical Linear Regression was used to analyse DHP‐18 scores, where blocks of variables are added progressively into the model to analyse the effect of a predictor variable after controlling for other variables. 33 , 34 The model was tested for the relationship between each DHP‐18 subscale with three blocks of independent variables, which were added sequentially. Model 1 included sociodemographic factors: gender, age group, ethnicity, employment status, education status, household income and housing type. For Model 2, diabetes‐related status comprising medication status, diabetes type and duration were added in addition to Model 1 variables. For Model 3, medical history variables, comprising number of comorbidities (0/1/2/3 or more) and previous diagnosis of any mental health condition (binary: yes/no) were added in addition to variables in Model 2. For Model 4, variables on health services access and self‐care variables were added in addition to Model 3. Model 1 to 4 were created for each of the respective DHP‐18 subscales. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were completed using R software version 3.4.3. 35

3. RESULTS

Data from 301 respondents were analysed. There was no missing data. Table 1 presents the baseline and sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Of the respondents, 45.2% were women, majority were of Chinese ethnicity (67.1%) and 24.2% were in the 40‐49 years age group. Majority of the respondents were employed (75.8%), married (61.1%), stayed in public housing (82.4%) and 41.2% held a university‐level education. On average, respondents stayed with four other persons and the majority stayed with their spouse/partner (61.1%).

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of survey respondents (N = 301)

| n(%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 21 to 29 | 40 (13.5%) |

| 30 to 39 | 57 (18.9%) |

| 40 to 49 | 73 (24.2%) |

| 50 to 59 | 72 (23.9%) |

| 60 and above | 59 (19.6%) |

| Gender | |

| Women (%) | 136 (45.2%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Chinese | 202 (67.1%) |

| Malay | 46 (15.3%) |

| Indian | 36 (12.0%) |

| Others | 17 (5.6%) |

| Education | |

| University and above | 124 (41.2%) |

| Pre‐University (International Baccalaureate/Cambridge GCE “A” Levels/Diploma) | 83 (27.6%) |

| Secondary/vocational training or education | 88 (29.2%) |

| Primary or no formal education | 6 (2.0%) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 228 (75.8%) |

| Unemployed | 41 (13.6%) |

| Not applicable | 32 (10.6%) |

| Employed | |

| Currently employed and working full time | 199 (66.1%) |

| Currently employed and working part time (less than 35 hours a week) | 23 (7.6%) |

| Currently employed but not working (due to partial lockdown) | 6 (2.0%) |

| Unemployed | |

| Unemployed for more than three months | 32 (10.6%) |

| Unemployed recently in the last three months | 9 (3.0%) |

| Not applicable | |

| Retired | 17 (5.6%) |

| Not applicable (Housewife/Homemaker/Currently still schooling) | 15 (5.0%) |

| Current martial status | |

| Single | 99 (32.9%) |

| Married | 184 (61.1%) |

| Divorced/separated | 11 (3.6%) |

| Widowed | 7 (2.3%) |

| Residential dwelling | |

| Smaller public housing/currently renting a room | 44 (14.6%) |

| Larger public housing | 204 (67.8%) |

| Private condominiums/apartments/landed property | 53 (17.6%) |

| Number of person(s) staying together in the same household | |

| Range (Min‐Max) | 1‐10 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.7) |

| Persons living together in the same household | |

| Children | 148 (49.2%) |

| Spouse/Partner | 184 (61.1%) |

| Relatives | 14 (4.6%) |

| Siblings | 63 (20.9%) |

| Domestic helper | 32 (10.6%) |

| Average monthly household income per person (Percentile) a | |

| Below $1,600 (1st to 30th) | 60 (19.9%) |

| Between $1,601 to $3,300 (31st to 60th) | 101 (33.6%) |

| Between $3,301 to $6,800 (61st to 90th) | 66 (21.9%) |

| Above $6,801 (91st and above) | 39 (13.0%) |

| Not comfortable to share | 35 (11.6%) |

Monthly household income per household member is calculated by taking the total gross household monthly income divided by the total number of family members living under the household, grouped by percentiles based on estimates from the national household income trends published by the Department of Statistics. 26

Table 2 presents the medical status and health services access of the respondents prior to COVID‐19, based on the type of diabetes. Majority of the respondents (68.4%) have T2DM, 26.2% have T1DM and the remaining were either unclear of their diabetes status or have other forms of diabetes. From the survey, 24.9% had diabetes duration between 5 and 9 years and 42.2% were on oral medication for their diabetes. Of the respondents, 68.2% have at least one of the six common diabetes comorbidities surveyed, nearly half of the respondents indicated having high cholesterol (48.5%) and hypertension (44.5%). A small number of respondents indicated previous diagnosis of a mental health condition (n = 18, 6.0%), with 7 (2.3%) still on treatment at the time of survey. Most of the respondents received care in a specialist outpatient clinic under a public healthcare institution (89.7%) and visit their doctors around 3‐4 times annually (72.4%) before COVID‐19 and lockdown.

TABLE 2.

Diabetes Medication, Comorbidities and Health Services Access by Diabetes Type (N = 301)

| Type of diabetes | Total N = 301 | Type 2 diabetes N = 206 | Type 1 diabetes N = 79 | Not sure/Unclear, Others (MODY, LADA) N = 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes duration | ||||

| <5 years | 65 (21.6%) | 42 (20.4%) | 15 (19.0%) | 8 (50.0%) |

| 5‐9 years | 75 (24.9%) | 38 (18.4%) | 18 (22.8%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| 10‐14 years | 59 (19.6%) | 46 (22.3%) | 12 (15.2%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| 15‐20 years | 45 (14.9%) | 31 (15.0%) | 13 (16.5%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| >20 years | 57 (18.9%) | 49 (23.8%) | 21 (26.6%) | 5 (31.2%) |

| Diabetes medication | ||||

| Oral medication | 127 (42.2%) | 110 (53.4%) | 8 (10.1%) | 9 (56.2%) |

| Insulin injection | 81 (26.9%) | 28 (13.6%) | 52 (65.8%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| Insulin and oral medication | 83 (27.6%) | 60 (29.1%) | 19 (24.1%) | 4 (25.0%) |

| I am not sure/Not on medication | 10 (3.3%) | 8 (3.88%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Existing comorbidities (indicated yes) | ||||

| High blood pressure/hypertension | 134 (44.5%) | 113 (54.9%) | 13 (16.5%) | 8 (50.0%) |

| High cholesterol | 146 (48.5%) | 118 (57.3%) | 22 (27.8%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| Heart disease | 21 (7.0%) | 17 (8.3%) | 2 (2.5%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Kidney disease | 21 (7.0%) | 10 (4.9%) | 3 (3.8%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Foot ulcers/amputations | 8 (2.7%) | 7 (3.40%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Diabetes eye complications | 33 (11.0%) | 24 (11.7%) | 7 (8.9%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| No. of comorbidities | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.18 (1.1) | 1.40 (1.1) | 0.61 (0.9) | 1.25 (1.4) |

| 0 | 100 (33.2%) | 49 (23.8%) | 46 (58.2%) | 5 (31.2%) |

| 1 | 92 (30.6%) | 62 (30.1%) | 23 (29.1%) | 7 (43.8%) |

| 2 | 75 (24.9%) | 67 (32.5%) | 6 (7.6%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| 3 or more | 34 (11.3%) | 28 (13.6%) | 4 (5.1%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Diagnosed with mental health condition or disorder before | ||||

| Yes | 18 (6.0%) | 15 (7.3%) | 3 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Currently on treatment for your mental health condition | 7 (2.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Usual location for diabetes follow‐up care, appointments and treatment | ||||

| GP Clinic | 10 (3.3%) | 10 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Polyclinic | 27 (9.0%) | 19 (9.2%) | 5 (6.3%) | 3 (18.8%) |

| Specialist Outpatient Clinic in Government Hospital | 270 (89.7%) | 181 (87.9%) | 75 (94.9%) | 14 (87.5%) |

| Private institution | 5 (1.7%) | 4 (1.94%) | 1 (1.27%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Frequency of visit to doctor for diabetes care before COVID‐19 and circuit breaker | ||||

| 1‐2 times/y | 67 (22.3%) | 43 (20.9%) | 15 (19.0%) | 9 (56.2%) |

| 3‐4 times/y | 218 (72.4%) | 153 (74.3%) | 60 (75.9%) | 5 (31.2%) |

| 5‐6 times/y | 15 (5.0%) | 9 (4.4%) | 4 (5.06%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| 7 or more times/y | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Abbreviations: LADA, Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in AdultsMODY, Maturity‐Onset Diabetes of the Young.

In response to questions pertaining to health services access, nearly all (97%) were able to obtain medications and medical supplies timely and receive care from their clinic safely during this period (94%), 81% of respondents indicated a willingness to explore tele‐consultation options should physical visits not be possible and 82% indicated that they were able to reach their doctor through either phone, messaging or email despite not attending clinic (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Health services access during COVID‐19 and partial lockdown. Graphic created with “likert” package in R software. 36

Subgroup analysis for age group and gender did not yield any significant findings. Across diabetes types, excluding patients with unknown or other diabetes type (LADA, MODY), more T1DM (92.4%) compared with T2DM (80.1%) were able to reach their doctor even if they do not visit the clinic physically (P = .02) (Figure S1).

A variable proportion of patients (40% to ~75%) maintained diabetes self‐care behaviours similar to pre‐COVID‐19 (Figure 2). Physical activity involvement was most impacted by COVID‐19 and lockdown; only 40% reported being able to keep the same level of physical activity. While 22% indicated that they were more frequently able to keep themselves physically active, 38% responded they were less physically active.

FIGURE 2.

Self‐care behaviours for diabetes patients during COVID‐19 and partial lockdown period. Graphic created with “likert” package in R software. 36

Similarly, the impact on self‐monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) was mixed, with a similar proportion indicating checking BG both less and more frequently (22% vs 21%, respectively). Taking diabetes medications as instructed (76%), confidence to manage diabetes (71%) and looking after oneself when sick (75%) were largely unaffected. Around a fifth of respondents were more frequently able to take their medications as instructed (21%) and look after themselves during sick days (20%). Of all self‐care behaviours examined, checking of BP had the lowest proportion of increased frequency (8%) with 29% of respondents checking their BP less frequently.

Subgroup analysis showed that there were no significant differences in self‐care behaviours across gender and age‐groups. Across the different types of diabetes, excluding observations unknown and other diabetes type, more T1DM patients (29%) as compared with T2DM patients (17%) monitored BG more frequently (P = .019). Conversely, T2DM patients monitored BG less frequently as compared with T1DM (25% vs 13%) (Figure S3). Likewise, there was a significant difference in BG checks across diabetes treatment type, with patients on insulin injections‐only doing so more frequently (30%) as compared with oral medications (18%) and oral medication plus insulin users (17%) (P = .047) (Figure S4).

Across the three DHP‐18 subscales, disinhibited eating (DE) had the highest score (µ = 43.3, SD = 17.2), followed by barriers to activity (BTA) (µ = 34.5, SD = 18.1). Psychological distress (PD) score subscale was lowest, with mean 20.6 and SD 20.0 (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the three subscales between T1DM and T2DM respondents. On average, patients on both oral medication and insulin scored higher compared with other treatment modalities (oral medication only, insulin only) for all three DHP‐18 subscales. This difference was significant for PD (P = .004) and DE subscale (P = .001) but not significant after adjusting for other covariates in the hierarchical regression (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Descriptive statistics of DHP by diabetes type and treatment type, excluding observations with unclear or other diabetes type (MODY/LADA) and observations that are not sure or not on medication, respectively

| N | Mean (SD) DHP‐18 score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress | p | Disinhibited eating | p | Barriers to activity | p | ||

| Overall | 301 | 20.6 (20.0) | 43.3 (17.2) | 34.5 (18.1) | |||

| Diabetes type | |||||||

| Type 1 diabetes | 79 | 23.7 (23.3) | 0.143 | 40.4 (17.1) | 0.115 | 33.0 (19.5) | 0.461 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 206 | 19.4 (18.5) | 44.0 (17.1) | 34.9 (18.1) | |||

| Treatment type | |||||||

| Insulin and oral medications | 83 | 26.8 (24.3) | 0.004 | 48.8 (20.2) | 0.001 | 38.6 (21.0) | 0.062 |

| Insulin injections | 81 | 19.0 (18.7) | 39.6 (14.9) | 32.7 (16.8) | |||

| Oral medications | 127 | 17.8 (16.9) | 42.0 (15.9) | 33.2 (16.7) | |||

Bold values indicate P values < .05.

Results of the hierarchical regression are presented in Table 4. Under the PD domain, older adults in the 50‐59 and 60 years and above age groups were associated with lower PD scores (β = −9.58, P = .022 and β = −10.20, P = .021 respectively). Individuals in 1st to 30th percentile income had lower PD scores (β = −9.76, P = .019). Indian ethnicity (β = 6.65, P = .034), T1DM (β = 12.92, P = .023), diagnosis of mental health conditions (β = 9.33, P = .043) and diabetes‐related comorbidities (β = 3.16, P = .007) were significantly associated with higher PD scores. Under health services and self‐care activities, respondents who were able to reach their healthcare provider despite not going to the clinic (β = −9.50, P = .002) had lower PD scores, while those who were less frequently able to look after themselves when sick (β = 13.53, P = .009) and keep themselves mentally active (β = 14.38, P = .008) were associated with higher PD scores.

TABLE 4.

Hierarchical linear regression results of DHP‐18 subscales

| Predictors | Psychological distress | Disinhibited eating | Barriers to activity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β_PD | CI | p | β_DE | CI | p | β_BTA | CI | p | |

| (Intercept) | 28.57 | 10.39 to 46.75 | 0.002 | 47.70 | 31.98 to 63.41 | <0.001 | 41.92 | 25.13 to 58.70 | <0.001 |

| Sociodemographic factors | |||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Women | Reference | ||||||||

| Men | 0.07 | −4.42 to 4.55 | 0.977 | −2.45 | −6.33 to 1.42 | 0.213 | −0.63 | −4.77 to 3.51 | 0.765 |

| Age category | |||||||||

| 21 to 29 | Reference | ||||||||

| 30 to 39 | 3.16 | −4.87 to 11.19 | 0.440 | 2.03 | −4.92 to 8.97 | 0.566 | 2.83 | −4.59 to 10.24 | 0.453 |

| 40 to 49 | −3.71 | −11.57 to 4.16 | 0.354 | −6.93 | −13.73 to −0.13 | 0.046 | 1.14 | −6.12 to 8.41 | 0.757 |

| 50 to 59 | −9.58 | −17.79 to −1.37 | 0.022 | −8.89 | −15.99 to −1.79 | 0.014 | 3.16 | −4.43 to 10.74 | 0.413 |

| 60 and above | −10.20 | −18.84 to −1.55 | 0.021 | −4.18 | −11.66 to 3.30 | 0.272 | 5.12 | −2.86 to 13.11 | 0.208 |

| Household Income (Percentile) | |||||||||

| >$6801 (91st and above) | Reference | ||||||||

| Below $600‐$1600 (1st to 30th) | −9.76 | −17.92 to −1.60 | 0.019 | 1.13 | −5.93 to 8.18 | 0.753 | −10.59 | −18.12 to −3.05 | 0.006 |

| Between $1601‐$3300 (31st to 60th) | −7.20 | −14.69 to 0.28 | 0.059 | −3.03 | −9.50 to 3.44 | 0.358 | −3.88 | −10.79 to 3.03 | 0.270 |

| Between $3301‐$6800 (61st to 90th) | −7.04 | −14.86 to 0.79 | 0.078 | −3.84 | −10.61 to 2.93 | 0.265 | −6.01 | −13.24 to 1.21 | 0.103 |

| Not comfortable to share | −5.91 | −14.93 to 3.11 | 0.198 | 1.07 | −6.73 to 8.87 | 0.786 | −8.87 | −17.20 to −0.54 | 0.037 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Chinese | Reference | ||||||||

| Indian | 6.65 | 0.51 to 12.79 | 0.034 | −0.15 | −5.46 to 5.16 | 0.955 | 0.35 | −5.32 to 6.02 | 0.904 |

| Malay | 1.64 | −5.97 to 9.26 | 0.671 | 6.34 | −0.24 to 12.92 | 0.059 | −2.65 | −9.68 to 4.38 | 0.458 |

| Others | −2.79 | −12.39 to 6.81 | 0.568 | −0.88 | −9.18 to 7.43 | 0.836 | 6.36 | −2.51 to 15.23 | 0.159 |

| Education level | |||||||||

| Pre‐University | Reference | ||||||||

| Primary and Lower | 8.08 | −8.32 to 24.49 | 0.333 | 5.35 | −8.84 to 19.54 | 0.458 | −1.52 | −16.67 to 13.63 | 0.844 |

| Secondary/ITE | −2.10 | −7.89 to 3.69 | 0.476 | −2.14 | −7.14 to 2.87 | 0.402 | −3.42 | −8.77 to 1.93 | 0.209 |

| University and Above | −4.41 | −10.32 to 1.49 | 0.142 | −1.58 | −6.69 to 3.52 | 0.542 | −4.88 | −10.33 to 0.57 | 0.079 |

| Employment status | |||||||||

| Employed | Reference | ||||||||

| Not applicable | 0.17 | −7.65 to 7.98 | 0.967 | −6.18 | −12.94 to 0.57 | 0.073 | −3.38 | −10.60 to 3.83 | 0.357 |

| Unemployed | 4.87 | −2.06 to 11.79 | 0.167 | −8.60 | −14.58 to −2.61 | 0.005 | −0.72 | −7.12 to 5.67 | 0.824 |

| Housing type | |||||||||

| Smaller public housing/renting | Reference | ||||||||

| Larger public housing | 1.13 | −5.14 to 7.39 | 0.724 | 1.63 | −3.79 to 7.05 | 0.554 | −0.79 | −6.58 to 4.99 | 0.787 |

| Private housing/landed property | −2.23 | −10.70 to 6.23 | 0.604 | 1.08 | −6.24 to 8.40 | 0.772 | −1.40 | −9.22 to 6.42 | 0.725 |

| Diabetes‐related status | |||||||||

| Diabetes type | |||||||||

| Not sure/Unclear, Others (MODY, LADA) | Reference | ||||||||

| Type 1 diabetes | 12.92 | 1.78 to 24.07 | 0.023 | −4.11 | −13.75 to 5.53 | 0.402 | 2.32 | −7.97 to 12.61 | 0.657 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2.65 | −7.17 to 12.46 | 0.596 | −2.15 | −10.64 to 6.34 | 0.618 | −2.15 | −11.22 to 6.91 | 0.641 |

| Diabetes duration | |||||||||

| <5 years | Reference | ||||||||

| 5 to 9 years | −2.94 | −9.34 to 3.46 | 0.367 | 1.31 | −4.23 to 6.84 | 0.643 | −4.04 | −9.96 to 1.87 | 0.179 |

| 10 to 14 years | 0.62 | −6.56 to 7.79 | 0.866 | 0.25 | −5.95 to 6.46 | 0.936 | −0.35 | −6.97 to 6.28 | 0.918 |

| 15 to 20 years | −1.38 | −9.21 to 6.45 | 0.729 | −4.96 | −11.73 to 1.82 | 0.151 | −8.34 | −15.57 to −1.10 | 0.024 |

| >20 years | −3.64 | −11.21 to 3.94 | 0.345 | −7.93 | −14.48 to −1.39 | 0.018 | 0.53 | −6.47 to 7.52 | 0.882 |

| Diabetes medication | |||||||||

| I am not sure/Not on medication | Reference | ||||||||

| Insulin and oral medications | 4.19 | −8.88 to 17.26 | 0.529 | 6.89 | −4.41 to 18.19 | 0.231 | 7.61 | −4.45 to 19.68 | 0.215 |

| Insulin injections | −4.42 | −17.86 to 9.02 | 0.518 | 1.84 | −9.78 to 13.46 | 0.755 | −0.17 | −12.58 to 12.24 | 0.978 |

| Oral medications | −1.44 | −13.88 to 11.00 | 0.820 | 1.19 | −9.57 to 11.95 | 0.827 | 1.88 | −9.61 to 13.37 | 0.747 |

| Medical history | |||||||||

| No. of Comorbidities | 3.16 | 0.88 to 5.43 | 0.007 | 2.49 | 0.52 to 4.46 | 0.014 | 1.11 | −0.99 to 3.21 | 0.299 |

| History of Mental Health Conditions | 9.33 | 0.29 to 18.36 | 0.043 | 1.66 | −6.15 to 9.47 | 0.676 | 6.86 | −1.48 to 15.20 | 0.107 |

| Health services access & self‐care | |||||||||

| Able to reach doctor while not going to clinic | |||||||||

| No | Reference | ||||||||

| Yes | −9.50 | −15.39 to −3.61 | 0.002 | −3.40 | –8.50 to 1.69 | 0.190 | –−7.53 | −12.97 to –2.09 | 0.007 |

| Check blood glucose level | |||||||||

| About the same | Reference | ||||||||

| Less frequently | 5.93 | −0.09 to 11.94 | 0.053 | 7.31 | 2.11 to 12.51 | 0.006 | 7.19 | 1.64 to 12.75 | 0.011 |

| More frequently | −0.70 | −6.95 to 5.55 | 0.826 | 1.27 | −4.13 to 6.68 | 0.644 | 7.82 | 2.05 to 13.59 | 0.008 |

| Keep physically active | |||||||||

| About the same | Reference | ||||||||

| Less frequently | 1.27 | −3.81 to 6.34 | 0.623 | 2.62 | −1.77 to 7.00 | 0.241 | −2.43 | −7.12 to 2.25 | 0.307 |

| More frequently | −0.48 | −7.11 to 6.14 | 0.886 | 1.70 | −4.03 to 7.43 | 0.560 | −5.38 | −11.51 to 0.74 | 0.084 |

| Eat a healthy diet | |||||||||

| About the same | Reference | ||||||||

| Less frequently | 1.39 | −5.13 to 7.91 | 0.675 | 4.74 | −0.90 to 10.38 | 0.099 | 1.80 | −4.22 to 7.82 | 0.556 |

| More frequently | 3.39 | −2.90 to 9.69 | 0.289 | 1.91 | −3.53 to 7.36 | 0.489 | 4.35 | −1.47 to 10.16 | 0.142 |

| Able to look after myself when sick | |||||||||

| About the same | Reference | ||||||||

| Less frequently | 13.53 | 3.47 to 23.60 | 0.009 | 8.07 | −0.63 to 16.78 | 0.069 | 16.84 | 7.54 to 26.13 | <0.001 |

| More frequently | −3.23 | −9.52 to 3.05 | 0.312 | −5.12 | −10.56 to 0.32 | 0.065 | −4.29 | −10.10 to 1.51 | 0.147 |

| Able to keep myself mentally active | |||||||||

| About the same | Reference | ||||||||

| Less frequently | 14.38 | 3.79 to 24.97 | 0.008 | 1.74 | −7.42 to 10.89 | 0.709 | 2.97 | –6.81 to 12.75 | 0.551 |

| More frequently | 1.31 | −4.08 to 6.69 | 0.633 | 3.13 | −1.52 to 7.79 | 0.186 | 7.21 | 2.24 to 12.19 | 0.005 |

| Observations | 301 | 301 | 301 | ||||||

| Model R2/R2 adjusted a | |||||||||

| Model 1 | 0.096/0.035 | 0.112/0.052 | 0.068/0.005 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 0.139/0.050 | 0.185/0.101 | 0.111/0.020 | ||||||

| Model 3 | 0.193/0.103 | 0.211/0.123 | 0.136/0.040 | ||||||

| Model 4 | 0.336/0.225 | 0.307/0.191 | 0.301/0.184 | ||||||

Bold values indicate P values < .05.

Abbreviations: LADA, Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in AdultsMODY, Maturity‐Onset Diabetes of the Young.

Variables in Model 1: Sociodemographic Factors; Model 2: Model 1 + Diabetes‐related status, Model 3: Model 2 + Medical history, Model 4: Model 3 + Health Services Access and Self‐Care status

Under the DE domain, the age groups between 40‐49 and 50‐59 years (β = −6.93, P = .046 and β = −8.89, P = .014 respectively) and unemployed status (β = −8.60, P = .005) were associated with lower DE score. Diabetes duration more than 20 years had an association with lower DE score (β = −7.93, P = .018) while diabetes‐related comorbidities were associated with higher DE score (β = 2.49, P = .014). Less frequent checking of BG was associated with higher DE score (β = 7.31, P = .006).

Under the BTA domain, low income (income percentile <$600) (β = −10.59, P = .006), unknown declared income (not comfortable to share) (β = −8.87, P = .037), and diabetes duration 15‐20 years (β = −8.34, P = .024) were associated with lower BTA score. Being able to contact their doctor despite not going to the clinic was associated with lower BTA scores (β = −7.53, P = .007). Under self‐care behaviours, checking BG more frequently (β = 7.82, P = .008) and less frequently (β = 7.19, P = .011) were both associated with higher BTA, being less frequently able to look after oneself when sick (β = 16.84, P < .001) and keeping oneself mentally active more frequently (β = 7.21, P = .005) was associated with higher BTA.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study assesses changes in health services access, diabetes self‐care practices, behavioural and psychological function of people with diabetes as a result of COVID‐19 and lockdown measures in Singapore. Our results indicate that access to health services and medications remained largely undisrupted for most patients with diabetes in Singapore during COVID‐19. Self‐care and management were impacted to a greater extent during the lockdown, and the direction of impact (positive and negative) across different subgroups was variable. While a pre‐COVID assessment of DHP‐18 domains scores was not available for comparison, results highlighted key covariates associated with greater dysfunction in patients surveyed.

4.1. Health services access

In our study, the majority of people with diabetes were able to access health services and obtain medications and diabetes medical supplies during the pandemic. This reflects Singapore's strategy in managing the pandemic and level of preparedness, drawing from experience with the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak. Despite postponing non‐critical appointments, patients with chronic diseases continued to receive medications and supplies via home delivery. 37 Alternative modes of consultation such as telemedicine were also introduced. More people with T1DM and those on insulin treatment were able to reach their doctor as compared with T2DM and on oral medications, which may be attributed to clinicians’ bias in reaching out to those with higher complexity needs.

Similarly, in a global survey distributed via social media, 38 the majority (79%) reported no issues in accessing diabetes supplies and medications. Nevertheless, a small minority of patients, particularly amongst the oldest age group, expressed unwillingness to explore teleconsultation in our study. Patients who are unable to utilise or adopt these technologies may be less able to cope and seek care when needed. Furthermore, as highlighted in our study, participants who were able to contact their doctors (through phone, messaging, email) despite not going to the clinic physically had lower psychological distress and barriers to activity scores on the DHP‐18.

4.2. Diabetes self‐care practices

Variability was observed in the magnitude and direction of impact in self‐care and diabetes management behaviours compared with pre‐COVID‐19. The onset of the pandemic brought about major changes in work, rest/leisure and social interactions that are intricately tied to different aspects of a patient's ability for self‐care and management of chronic diseases. The bi‐directional change in self‐care and management illustrate that change is likely contextual for each patient.

For instance, adherence to diabetes medications, self‐care during sick days and confidence in managing diabetes were largely unaffected, with a sizeable proportion (~20%‐25%) being able to engage in these behaviours more frequently, including monitoring BG. In a study looking at the impact of lockdown on glycaemic control in 307 people with T1DM using flash glucose monitoring (FGM), there was an improvement in glycaemic control with increased time‐in‐range. The authors postulated that the lockdown could have contributed to more time for self‐management from greater stability in schedules, healthier meals and more time for treatment adjustments. 39

However, greater stability in schedules does not necessarily translate to adherence to a healthier diet in this study. This variability in in diet was also observed amongst patients with diabetes in Japan. 40 Ruiz‐Roso et al reported increased intake of not only vegetables but also snacks and sugary foods during the lockdown period in a Spanish population. 12 A hospital‐based survey from South India noted increased consumption of fruits and vegetables and reduced unhealthy snacking, 16 whereas a study in North India reported increased carbohydrate consumption and snacking. 41

Likewise, in our study, physical activity involvement was the most negatively affected, with 38% of respondents less frequently able to keep physically active. This finding is not surprising since over 80% of Singaporeans live in public housing comprising flats 42 with limited space for physical activity. With communal spaces and sports facilities closed during the lockdown period, it would have been difficult to maintain usual physical activities. Our findings are similar to others reporting reductions in physical activity and resultant weight gain in people with diabetes. 12 , 41 , 43 Assaloni et al looked specifically at physical activity and variation in glycaemic values in T1DM during this pandemic and found negative outcomes with decreased physical activity and increased glycaemic levels. 43 Nevertheless, it is worth noting that in our study, 40% maintained their physical activity levels and a further 22% were able to engage in physical activity more frequently compared with pre‐COVID‐19. Given the unexpected and prolonged duration of safe distancing measures during this period, advice and guidance on home‐based exercises should be recommended.

These variable responses to lifestyle modification strategies and self‐care behaviours in diabetes suggest that different social, economic and cultural nuances across different patient groups and countries play a role in how patients adapt and manage their circumstances during a pandemic.

4.3. DHP‐18 subscales

Several key factors were highlighted to be associated with greater dysfunction in different domains of DHP‐18 amongst diabetes patients. We identified that previous diagnosis of mental health conditions and increasing number of diabetes‐related comorbidities were associated with greater PD (dysphoric mood, feelings of hopelessness, irritability) scores under the DHP‐18 subscale. T1DM patients alongside those with Indian ethnicity was found to be associated with significantly higher PD. In comparison with other locally conducted studies utilising DHP‐18, poor glycaemic control, indicated by higher glycated haemoglobin level, was found to be associated with higher PD. 31 However, the association with Indian ethnicity was not observed. 30 , 31 Nonetheless, the association between depressive symptoms and Indian ethnicity was identified in another local study using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. 44 The number of diabetes‐related comorbidities was also positively associated with DE domain (uninhibited eating control, response to food cues and emotional arousal). Interestingly, DE scores were lower amongst unemployed individuals, and the frequency of adhering to a healthy diet was not associated with DE. One plausible explanation is that the sudden introduction of alternative work arrangements such as telecommuting may have brought about significant disruptions in the routine of employed individuals as compared with unemployed individuals. In contrast to previous association studies, 31 we did not observe a significant association for type of diabetes treatment with higher DE and BTA dysfunction.

Because of the cross‐sectional and anonymous nature of the study, we were unable to obtain pre‐COVID‐19 estimates of the DHP‐18 scores. When comparing this study with local literature utilising DHP‐18, 30 both PD and DE domain scores did not differ substantially. However, BTA score was significantly higher in our study. The referenced study comprised only T2DM patients, unlike our study which has over a quarter of T1DM patients and twice as many Indian respondents (27.9% vs 12.0%). Thus, the higher BTA score should be interpreted with caution as it may be attributed to pandemic mitigation measures, such as restricted social gatherings, change in dietary patterns, stay‐home measures during lockdown and the added risk for severe outcomes for COVID‐19 infections amongst people with diabetes.

4.4. Implications for clinical practice

Our study highlights that patients with T1DM and diabetes‐related comorbidities are associated with greater psychological distress. Similarly, a previous diagnosis of mental health condition and being of Indian ethnicity were also associated with higher psychological distress. This latter finding should be interpreted with caution as the number of people with a mental health condition and of Indian ethnicity were small in this study (N = 36 and N = 18, respectively). Nevertheless, greater attention and care may be provided to these patients through screening of mental health and psychosocial needs of patients routinely. 44 Likewise, ensuring that patients have an avenue to contact physicians if they are not able to go to the clinic as well as identifying strategies to empower patients to look after themselves when sick can alleviate psychological distress and barriers to activity.

4.5. Strengths and limitations

This study is important and relevant during the current pandemic and included a detailed questionnaire assessing health services access and well‐being for people with diabetes, a chronic disease, in Singapore. However, there are a few limitations which limit generalisability of our findings to other study populations. Because of the cross‐sectional 45 and anonymous nature of the study, we were unable to ascertain baseline DHP‐18 before COVID‐19 and perform follow‐up assessment. The study recruited a convenience sample from multiple sources. Hence, the usual limitations associated with convenience sampling apply. The study only recruited English‐literate respondents via an online survey requiring a degree of IT savviness. In addition, self‐reported classification of type of diabetes may be potentially inaccurate. Furthermore, most were receiving care from specialist outpatient clinics as noted from the study findings and thus, may not be representative of all people with diabetes in Singapore. There may be concern over the timing of this study, which spans two phases of the COVID‐19 response measures. However, the lifting of restriction measures from phase 1 to phase 2 and from phase 2 to the study‐end was gradual in Singapore. In other words, the immediate differences in the stringency of the measures may not change drastically overnight between the Circuit Breaker to Phase 1 or even Phase 1 to Phase 2. Hence, our findings are likely to remain valid. Lastly, we were not able to correlate clinical parameters such as glycated haemoglobin to identify associations with clinical outcomes.

5. CONCLUSION

Although health services delivery may have been modified and adapted, people with diabetes in Singapore continued to be able to access health services and medical care during the COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown. While majority of patients remained confident in managing their health and medications, other aspects such as physical activity involvement, checking of BP and BG were performed less frequently. People with diabetes with prior mental health conditions, T1DM and multiple comorbidities are at higher risk of greater psychological dysfunction. The disproportionate psychological and behavioural impact of the pandemic suggests that certain patient groups may require additional support.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

EY conceived and designed the study, collected the data and wrote the manuscript. TSG and WHL contributed to the design of the study, performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. LYY, THH, LYS, LSC, SCF, TS contributed to data collection and writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the participants in the study as well as the patient support groups who disseminated the survey weblink to their members. They also thank Oxford University Innovation Ltd for granting permission to use the Diabetes Health Profile 18. Oxford University Innovation Limited is exclusively licensed to grant permissions to use the Diabetes Health Profile. Individuals keen on using the Diabetes Health Profile may contact Oxford University Innovation at healthoutcomes@innovation.ox.ac.uk

Yeoh E, Tan SG, Lee YS, et al. Impact of COVID‐19 and partial lockdown on access to care, self‐management and psychological well‐being among people with diabetes: A cross‐sectional study. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14319. 10.1111/ijcp.14319

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Campos JADB, Martins BG, Campos LA, Marôco J, Saadiq RA, Ruano R. Early psychological impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic in brazil: a national survey. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):2976. 10.3390/jcm9092976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jewell JS, Farewell CV, Welton‐Mitchell C, Lee‐Winn A, Walls J, Leiferman JA. Mental Health During the COVID‐19 pandemic in the united states: online survey. JMIR Form Res. 2020;4(10):e22043. 10.2196/22043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jia R, Ayling K, Chalder T, et al. Mental health in the UK during the COVID‐19 pandemic: cross‐sectional analyses from a community cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e040620. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113190. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luo X, Estill J, Wang Q, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113193. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCracken LM, Badinlou F, Buhrman M, Brocki KC. Psychological impact of COVID‐19 in the Swedish population: Depression, anxiety, and insomnia and their associations to risk and vulnerability factors. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63(1):e81. 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rodríguez‐Rey R, Garrido‐Hernansaiz H, Collado S. Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1540. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhao SZ, Wong JYH, Luk TT, Wai AKC, Lam TH, Wang MP. Mental health crisis under COVID‐19 pandemic in Hong Kong. China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:431‐433. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912‐920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the covid‐19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510‐512. 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joensen LE, Madsen KP, Holm L, et al. Diabetes and COVID‐19: psychosocial consequences of the COVID‐19 pandemic in people with diabetes in Denmark—what characterizes people with high levels of COVID‐19‐related worries? Diabet Med. 2020;37(7):1146‐1154. 10.1111/dme.14319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ruiz‐Roso MB, Knott‐Torcal C, Matilla‐Escalante DC, et al. COVID‐19 lockdown and changes of the dietary pattern and physical activity habits in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2327. 10.3390/nu12082327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alshareef R, Al Zahrani A, Alzahrani A, Ghandoura L. Impact of the COVID‐19 lockdown on diabetes patients in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(5):1583‐1587. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Verma A, Rajput R, Verma S, Balania VKB, Jangra B. Impact of lockdown in COVID 19 on glycemic control in patients with type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(5):1213‐1216. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonora BM, Boscari F, Avogaro A, Bruttomesso D, Fadini GP. Glycaemic Control among people with type 1 diabetes during lockdown for the SARS‐CoV‐2 outbreak in Italy. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(6):1369‐1379. 10.1007/s13300-020-00829-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sankar P, Ahmed WN, Mariam Koshy V, Jacob R, Sasidharan S. Effects of COVID‐19 lockdown on type 2 diabetes, lifestyle and psychosocial health: a hospital‐based cross‐sectional survey from South India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(6):1815‐1819. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Su‐Yen G, Horn LC, Mong BY. Diabetes care in Singapore. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2015;30(2):95–99. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee WC, Ong CY. Overview of rapid mitigating strategies in Singapore during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Public Health. 2020;185:15‐17. 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ministry of Health . Circuit Breaker To Minimise Further Spread Of COVID‐19. 2020. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news‐s/details/circuit‐breaker‐to‐minimise‐further‐spread‐of‐covid‐19. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 20. Ministry of Health . End of circuit breaker, phased approach to resuming activities safely. 2020. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news‐s/details/end‐of‐circuit‐breaker‐phased‐approach‐to‐resuming‐activities‐safely. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 21. Ministry of Health . End of circuit breaker phased approach to resuming healthcare services. 2020. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news‐s/details/end‐of‐circuit‐breaker‐phased‐approach‐to‐resuming‐healthcare‐services. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 22. Ministry of Health . Moving into phase two of re‐opening. 2020. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news‐s/details/moving‐into‐phase‐two‐of‐re‐opening. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 23. Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID‐19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta‐analysis. J Infect. 2020;81(2):e16‐e25. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID‐19‐related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population‐based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823‐833. 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ong SWX, Young BE, Leo Y‐S, Lye DC. Association of higher body mass index with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in younger patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(16):2300–2302. 10.1093/cid/ciaa548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hartmann‐Boyce J, Morris E, Goyder C, et al. Diabetes and COVID‐19: risks, management, and learnings from other national disasters. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):1695‐1703. 10.2337/dc20-1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Department of Statistics Singapore . Key Household Income Trends, 2019. Singapore; 2020. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/‐/media/files/publications/households/pp‐s26.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 28. Meadows KA, Abrams C, Sandbaek A. Adaptation of the Diabetes Health Profile (DHP‐1) for use with patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: psychometric evaluation and cross‐cultural comparison. Diabet Med. 2000;17(8):572‐580. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Health Outcomes Insights Ltd . The Diabetes Health Profile EBook – development and Applications v.2. 2016. https://www.healthoutinsights.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Diabetes-Health-Profile-eBook-Development-Applications-20190327.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 30. Tan ML, Khoo EY, Griva K, et al. Diabetes health profile‐18 is reliable, valid and sensitive in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2016;45(9):383‐393. https://www.annals.edu.sg/pdf/45VolNo9Sep2016/MemberOnly/V45N9p383.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Co MA, Tan LSM, Tai ES, et al. Factors associated with psychological distress, behavioral impact and health‐related quality of life among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(3):378‐383. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Venkataraman K, Tan LSM, Bautista DCT, et al. Psychometric properties of the problem areas in diabetes (PAID) instrument in Singapore. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136759. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hierarchical Regression . The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks, California 91320: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2018. 10.4135/9781506326139.n304 [DOI]

- 34. Lewis M. Stepwise versus hierarchical regression: Pros and cons. Southwest Educational Research Association 2007 Annual Meeting. 2007. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED534385.pdf

- 35. R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2019. https://www.r‐project.org/. Accessed November 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bryer J, Speerschneider K. 2016. Likert: analysis and visualization likert items. https://cran.r‐project.org/web/packages/likert/index.html. Accessed November 13, 2020.

- 37. Tay TF. Coronavirus: Public healthcare institutions waive medicine delivery fees for patients. 2020. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/coronavirus‐public‐healthcare‐institutions‐waive‐medicine‐delivery‐fees‐for‐patients. Accessed November 13, 2020.

- 38. Scott SN, Fontana FY, Züger T, Laimer M, Stettler C. Use and perception of telemedicine in people with type 1 diabetes during the COVID‐19 pandemic—results of a global survey. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2021;4(1):180. 10.1002/edm2.180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fernández E, Cortazar A, Bellido V. Impact of COVID‐19 lockdown on glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;166:108348. 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kishimoto M, Ishikawa T, Odawara M. Behavioral changes in patients with diabetes during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Diabetol Int. 2021;12(2):241–245. 10.1007/s13340-020-00467-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ghosh A, Arora B, Gupta R, Anoop S, Misra A. Effects of nationwide lockdown during COVID‐19 epidemic on lifestyle and other medical issues of patients with type 2 diabetes in north India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(5):917‐920. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Housing Development Board . Public housing – a Singapore icon. 2020. https://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/inf oweb/about‐us/our‐role/public‐housing‐a‐singapore‐icon. Accessed November 13, 2020.

- 43. Assaloni R, Pellino VC, Puci MV, et al. Coronavirus disease (Covid‐19): How does the exercise practice in active people with type 1 diabetes change? A preliminary survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;166:108297. 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sim H, How C. Mental health and psychosocial support during healthcare emergencies – COVID‐19 pandemic. Singapore Med J. 2020;61(7):357‐362. 10.11622/smedj.2020103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carlson MDA, Morrison RS. Study design, precision, and validity in observational studies. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(1):77‐82. 10.1089/jpm.2008.9690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.