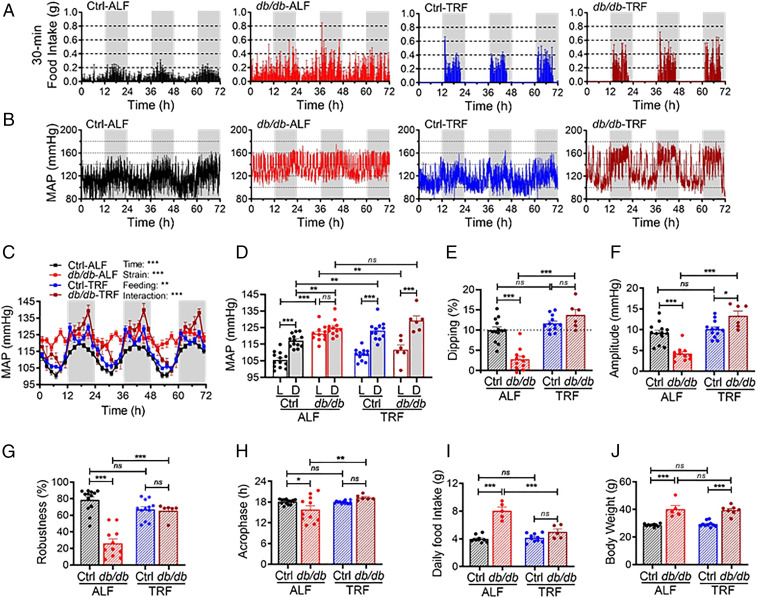

Fig. 2.

Imposing a food intake circadian rhythm by TRF prevents db/db mice from the development of BP nondipping. Both 6-week-old db/db and control (db/+) mice were fed ALF or 8-h TRF. Food intake was measured by indirect calorimetry 12 wk after TRF or ALF when mice were 18 wk of age. BP was monitored by telemetry 10 wk after TRF or ALF when mice were 16 wk of age. (A) Daily profiles of food intake in 30-min intervals over 72 h during the light and dark phases, shown in white and gray, respectively. Ctrl-ALF (n = 10), db/db-ALF (n = 5), Ctrl-TRF (n = 10), and db/db-TRF (n = 5). (B) Representative continuous MAP recordings by telemetry in 10-s intervals over 72 h during the light and dark phases. (C) Daily profiles of the MAP in 2-h intervals over 72 h during the light and dark phases in Ctrl-ALF (n = 13), db/db-ALF (n = 11), Ctrl-TRF (n = 12), and db/db-TRF (n = 6) mice. (D) The 12-h average MAP during the light (L) and dark (D) phase. (E) MAP dipping (percentage of MAP decrease during the light phase compared to the dark phase). The dashed line indicates a 10% dipping. (F−H) Amplitude (F), robustness (G), and acrophase (H) of the MAP circadian rhythm. (I and J) Daily food intake (I) and body weight (J) were measured 10 to 12 wk after ALF or TRF. The data were analyzed by three-way ANOVA (C and D) and two-way ANOVA (E−J) with multiple comparisons test and were expressed as the mean ± SE (SEM). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.