Abstract

We present a case of primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium. This rare tumor occurred in a 43-year-old woman with a pure primary yolk sac tumor. The tumor resembled yolk sac tumor morphology of the ovary. Tumor cells expressed SALL4, AFP, GPC-3, and AE1/AE3 and were focal positive for PAX8. EMA, ER, and PR, among others, were negative. We further analyzed 29 reported cases of this rare tumor in the literature. In total, 17 of 30 patients (57%) had pure endometrial yolk sac tumor, and 13 (43%) had a concomitant somatic neoplasm (endometrial adenocarcinoma was the most common). Although the average age was 52 years (range: 24–87 years), patients with pure yolk sac tumor were younger than those with concomitant somatic tumors, with a mean age of 44.41 years (24–68 years) versus 61.92 years (28–87 years), P = 0.008. Patients with endometrial yolk sac tumor combined with somatic tumor tend to have a slightly higher stage and a poor prognosis.

Keywords: Yolk sac tumor (YST), endometrial, SALL4, differential diagnosis, prognosis

Introduction

Yolk sac tumor (YST), also known as an endodermal sinus tumor, is the third most common form of malignant ovarian germ cell neoplasms, followed by dysgerminoma and immature teratomas. 1 It is one of the most common malignant ovarian neoplasms of childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. Although YST usually originates from the gonads (ovary and testis), it occasionally arises from midline extragonadal regions, such as the sacrococcygeal region, mediastinum, and retroperitoneum. Approximately 20% of female patients experience extragonadal YST (EGYST), 2 and the vagina is the most common site of YST growth in infants and young children. 3 Primary YST of the endometrium is very rare. 4 The first case of primary YST of the endometrium was reported in 1980. 3 To the best of our knowledge, only 29 cases have been reported in the literature to date. We report a new case of primary endometrial YST and have a systematic review of the literature.

Case report

A 43-year-old woman was admitted with abnormal vaginal bleeding for 2 months and epigastric pain for 4 months. In the local hospital, she received a transvaginal ultrasound, which showed a hyperechoic endometrial mass. A 4-cm prominent mass was observed on the left side of the uterine isthmus by hysteroscopy. A pelvic computerized tomography (CT) scan revealed a uterine mass with no significantly enlarged lymph nodes. Pelvic-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a mild enhancement of the lesion, and the lesion seemingly not invaded muscular layer (Figure 1). An increasing level of alpha fetoprotein (AFP; 1465 µg/mL, reference level < 20 ng/mL) was observed. The serum levels of β-HCG, CA125, CA199, and CEA were normal. The diagnostic fractional curettage specimen was diagnosed as endometrial carcinoma in a local hospital. For treatment, the dilatation and curettage specimen was subjected to a consultation diagnosis in our department, and the diagnosis was modified to primary YST of the endometrium.

Figure 1.

Pelvic-enhanced MRI showed mild enhancement of the lesion, and the lesion seemingly not invaded muscular layer.

The patient underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, bilateral ovary biopsies, bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy, para-aortic lymphadenectomy, omentectomy, and appendectomy. The intraoperative exploration revealed that the uterus was enlarged equivalent to 50 gestational days. No abnormalities were observed on the surface of the uterus, bilateral ovaries, or oviducts, and no enlargement or hardening of the pelvic and abdominal para-aortic lymph nodes was observed.

Adjuvant chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) was performed for six cycles. The tumor response was monitored by serial determination of the serum level of AFP, which was decreased to normal before the first cycle of chemotherapy. The patient was alive without evidence of disease for 15 months.

The uterus measured 12.5 × 9.5 × 5.5 cm3. An area of hemorrhage and necrosis was observed at the lower uterine segment. The residual tumor infiltrated the superficial myometrium, less than half of the myometrium. The tumor did not involve the cervix, fallopian tubes, bilateral ovaries, or omentum. No metastatic tumor was observed in 12 pelvic lymph nodes or in 3 para-aortic lymph nodes. The case was classified as stage IA according to the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) staging system. 5

Microscopically, pure endometrial YST without any other type of germ cell tumor or somatic carcinoma components was found (Figure 2). A reticular pattern coexisted with papillary growth. The reticulum comprised a labyrinth of channels lined by primitive cells expanding to form microcysts with flattened, clear atypical epithelial cells. Papillary growth showed papillary fibrovascular structures in which a central blood vessel with tumor cells projects into the surrounding space (endodermal sinuses, Schiller–Duval bodies (S-D bodies)). Hyaline globules were observed in the cells. The stroma was hypocellular and myxoid.

Figure 2.

Histological features of endometrial YST. Multiple separated tumor tissue with a small piece of normal endometrium (A ×20), most area showing a tubulopapillary pattern (B ×40) with classical Schiller–Duval bodies (C ×100), a microcystic or reticular pattern (D ×100), and focal glandular pattern (E ×400), hyaline globules in the cytoplasm (F ×200).

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were diffuse positive for AFP, SALL4, GPC-3, and AE1/AE3. They were focal positive for PAX8. ER, PR, CD30, OCT4, HNF-1β, Napsin A, and CD117 were all negative (Figure 3).

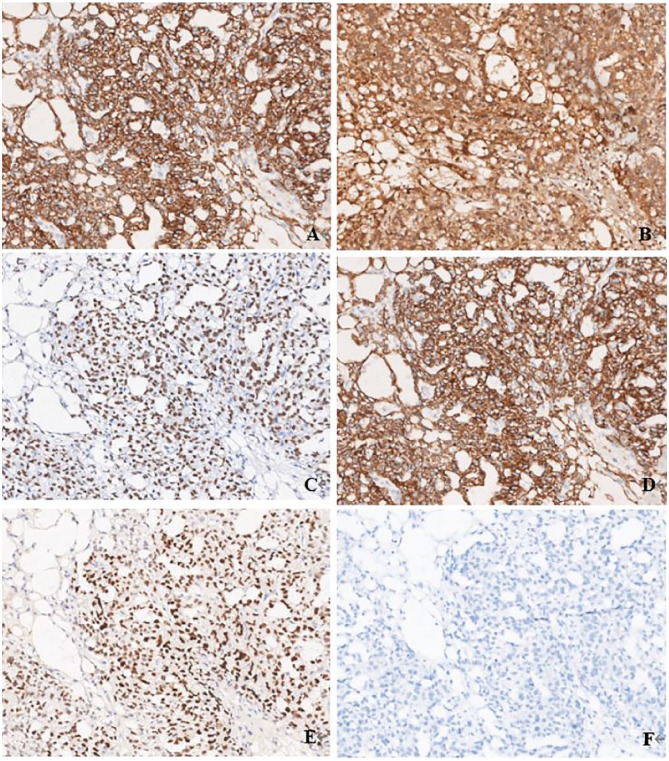

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical profile of endometrial YST. Diffuse positive for AFP (A ×100), GPC-3 (B ×100), SALL-4 (C ×100), and AE1/AE3 (D ×100). Focal positive for PAX8 (E ×100) and negative for EMA (F ×100).

Results

We summarized the clinicopathological features, therapies, and prognosis of 30 primary endometrial YSTs (the present case and 29 cases from the literature, Table 1). The average patient age was 52 years (range: 24–87 years). The mean tumor size was 6.94 cm (range: 1.3–19.0 cm). The main clinical symptom was abnormal vaginal bleeding. Increasing serum levels of AFP were reported in 18 of 19 patients with recorded materials and in only 1 patient with a normal AFP level.

Table 1.

Summary of clinicopathologic features of primary endometrial YSTs.

| Case | Age (years) | AFP level | Symptoms | Tumor size (cm) | Surgery | Associated component | Metastasis site | Chemotherapy | Radiotherapy | FIGO stage | Follow up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 3 | 28 | 380 | Metrorrhagia, pelvic pain | Unknown | TAH BSO | None | None | VAC | No | IB | REC, 2 (liver); DOD, 8 |

| 2 6 | 27 | 1580 | Metrorrhagia | 2.4 | TAH BSO OMT | None | None | VAC | No | IA | NED > 12 |

| 3 7 | 24 | 3600 | Abdominal pain | 10 | SH BSO | None | ovary | VAC | Yes | IVA | REC, (unknown); DOD, 24 |

| 4 2 | 49 | NA | Metrorrhagia | 1.3 | TAH BSO ILD | None | None | No | Yes | IB | NED > 28 |

| 5 8 | 59 | 25,385 | Postmenopausal bleeding | Unknown | TAB BSO PLD PALD | EC | Liver | BEP EP | Yes | IA | REC, 16; AWD > 16 |

| 6 9 | 65 | 2306 | Watery discharge | 7 | MRH BSO PLD PALD | Carcinosarcoma | LN | TP | No | IIIC2 | NA |

| 7 10 | 42 | 18,530 | AVB | 6 | TAH BSO | None | None | PVB | No | IA | NED > 24 |

| 8 11 | 30 | 1762 | AVB | 6.5 | TAH | None | None | BEP | No | II | NED > 72 |

| 9 12 | 29 | 3593.4 | AVB | 6.7 | MRH LSO PLD PALD | None | None | BEP | No | II | NED > 39 |

| 10 13 | 28 | 1522 | AVB | 6 | TAH BSO PLD OMT appendectomy, partial sigmoidectomy | EC | Peritoneum omental | PTX, ADM, DDP, CBDCA, MTX, Act-D, VP16, BLM, pingyangmycin, VCR, FUDR, oxaliplatin, CPA | No | IVB | REC, 2; AWD |

| 11 14 | 31 | 242.3 | Menorrhagia | 4 | None | None | None | BEP | No | IA | NED > 24 |

| 12 15 | 57 | 31,844 | Abdominal pain, weight loss | 10.5 | TAH BSO OMT PLD PALD | None | Liver ovary lung vertebrae | BEP | No | IVB | DOD < 2 |

| 13 15 | 44 | >30,000 | AVB, vaginal mass prolapsing | 19 | TAH BSO OMT PLD PALD | None | None | BEP | No | IB | NED > 6 |

| 14 16 | 63 | 244.6 (6 wk PO) | Postmenopausal bleeding | 12 | None | None | Ovary omentum | BEP | No | IVB | NED 6 |

| 15 4 | 71 | NA | AVB | NA | Yes | SC EC | NA | NA | NA | IIIA | DOD, 19 |

| 16 4 | 55 | NA | AVB | NA | Yes | Complex hyperplasia | NA | Yes | Yes | II | DOD, 16 |

| 17 4 | 59 | NA | AVB, uterine mass | NA | NA | EC | NA | Yes | No | IB | LFT |

| 18 4 | 68 | NA | AVB, uterine mass | NA | Yes | None | NA | Yes | No | IV | DOD, 14 |

| 19 4 | 77 | NA | AVB, uterine mass | NA | NA | EC UDC | NA | NA | NA | IIIC | LFT |

| 20 4 | 64 | NA | AVB | NA | Yes | AC | NA | Yes | Yes | IIIA | DOD, 23 |

| 21 4 | 87 | NA | AVB | NA | Yes | AC | NA | Yes | No | II | AWD, 7 |

| 22 4 | 61 | NA | AVB | NA | Yes | None | NA | Yes | No | IA | AWD, 8 |

| 23 4 | 63 | NA | AVB | NA | Yes | MMMT | NA | Yes | Yes | IIIC1 | NED, 5 |

| 24 4 | 62 | NA | AVB | NA | Yes | SC | NA | Yes | No | IB | AWD, 30 |

| 25 4 | 77 | NA | AVB | NA | Yes | SC, CCC, UDC | NA | Yes | No | IIIC2 | AWD, 17 |

| 26 17 | 64 | 15,918 | Abdominal distension | NA | NA | None | NA | NA | NA | IVB | DOD, 2.5 |

| 27 18 | 27 | >800 | AVB | 5.4 | TAH OMT PLD PALD | None | None | TC | No | IA | NED > 14 |

| 28 19 | 38 | Normal | AVB, prolonged menstruation | NA | TAH BSO OMT PLD PALD | CCC | None | BEP | No | IVB | NED > 24 |

| 29 20 | 68 | 133.4 (6 days PO) | AVB | 3.3 | TAH BSO OMT PLD PALD | None | No | BEP | No | II | NED > 6 |

| 30 present | 43 | 1465 | AVB, epigastric pain | 4 | TAH BSO PLD | None | No | BEP | No | IA | NED, 15 |

PO: postoperatively; YST: yolk sac tumor; AVB: abnormal vaginal bleeding; TAH: total abdominal hysterectomy; BSO: bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; OMT: omentectomy; SH: supracervical hysterectomy; ILD: iliac lymphadenectomy; PLD: pelvic lymphadenectomy; PALD: paraaortic lymphadenectomy; MRH: modified radical hysterectomy; LSO: left salpingo-oophorectomy; EC: endometrioid adenocarcinoma; SC: serous carcinoma; UDC: undifferentiated carcinoma; AC: adenocarcinoma; MMMT: malignant mixed Mullerian tumor; CCC: clear cell carcinoma; VAC: vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide; BEP: bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin; EP: etoposide and cisplatin; TP: taxol and cisplatin; PVB: bleomycin, vincristine, and cisplatin; PTX: paclitaxel; ADM: adriamycin; DDP: cisplatin; CBDCA: carboplatin; MTX: methotrexate; Act-D: actinomycin D; VP16: etoposide; BLM: bleomycin; VCR: vincristine; FUDR: 5-fluoro-2-deoxy-β-uridine; CPA: cyclophosphamide; REC: recurrence; DOD: dead from the disease; NED: no evidence of disease; AWD: alive with disease; LFT: lost to follow-up; NA: not available; AFP: alpha fetoprotein.

Among 16 of 25 patients with detailed surgical resection ranges, 3/16 underwent bilateral adnexal resection. The FIGO stages were as follows: I (n = 11), II (n = 5), III (n = 6), and IV (n = 7). In total, 26/30 (87%) patients underwent chemotherapy after the operation. BEP was the most common chemotherapy regimen in 11/26 patients (42%). Only 6 patients (6/30, 20%) endured radiotherapy.

Of all 30 patients, 17 (57%) had pure endometrial YST, and 13 (43%) had a concomitant somatic neoplasm representing <10% to 90% of the tumor. The somatic neoplasms followed the histological types endometrial adenocarcinoma (n = 4), carcinosarcoma (n = 2), clear cell carcinoma (n = 1), adenocarcinoma (n = 1), serous carcinoma (n = 1), serous carcinoma and endometrial adenocarcinoma (n = 1), serous carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma (1), and endometrial complex hyperplasia (n = 1). Patients with pure YST were younger than those with a concomitant somatic tumor (range: 24–68 years (mean: 44.5 years) vs 28–87 years (mean: 61.92 years), P = 0.008).

Of the 30 cases, follow-up information was obtained for 90% (27/30) of the patients. The mean follow-up time was 17.25 months (range: 2–72 months); 48.1% (13/27) of patients had no evidence of disease during the follow-up time, 8 patients (8/27, 29.6%) died of disease (range: 2.5–24 months), and 6 patients (6/27, 22.2%) were alive with disease (range: 7–30 months). The rate of early-stage pure endometrial YST was 70.6% (12/17); it was 38.5% (5/13) for those combined with somatic tumors. There was no statistical differences (P = 0.082). The OS and DES for pure endometrial YSTs were slightly longer than for somatic tumor, though with no statistical differences (mean OS: 48.1 vs 21.9 months, P = 0.690; mean DFS: 53.0 vs 20.7 months, P = 0.485) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The OS (a) and DFS (b) of pure endometrial YST were slightly longer than those of combined somatic tumor of endometrial YSTs, though with no statistical differences (P = 0.690 and P = 0.485).

Discussion

The histogenesis of extragonadal YST remains speculative and controversial. There are four potential mechanisms by which a germ cell neoplasm can arise in the endometrium. 10 The first is the aberrant migration of primordial germ cells in a lateral direction during embryogenesis, which can remain in the basal layer of the endometrium for many years. The second potential mechanism is metastasis from occult ovarian YST. Residual fetal tissues remaining in the uterus because of an incomplete abortion and somatic cells that have undergone aberrant differentiation by which YST originates in unusual sites are the other two potential mechanisms.

Patients with pure YSTs were younger than those with a concomitant somatic tumor. Therefore, pure endometrial YST and endometrial YST with somatic tumors may have had different histogeneses. Pure endometrial YSTs may originate from pluripotent germ cells, while endometrial YSTs with somatic tumors may arise from malignant pluripotent somatic stem cells or possibly via “retrodifferentiation,” by which a differentiated cell transforms into a more primitive form. 21 Reports of ovarian YST arising from an endometrioid carcinoma support this hypothesis.9,22,23 YSTs of the female genital tract in older women are commonly derived from somatic epithelial neoplasms. 24 AFP is used as a significant follow-up indicator, but only a few patients have normal serum AFP levels. 19

Since primary endometrial YST is rare, inexperienced pathologists likely make an incorrect diagnosis, especially in biopsy specimens. In particular, the immunohistochemical profile overlaps with that of YST and carcinoma; for example, AE1/AE3 is positive in the current YST, which is not a good marker for differential diagnosis of carcinoma. 25 Although HNF-1β and PAX8 can be patchy positive in YST, 26 both are rather than diffuse positive in clear cell carcinoma. SALL4 is a useful marker for diagnosis when combined with GPC-3 and AFP. 27 Overall, a panel of markers is necessary for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of YST at rare sites (Table 2).

Table 2.

Application of immunohistochemistry in differential diagnosis of germ cell tumors.

| AE1/AE3 | HNF-1β | PAX8 | SALL4 | GPC-3 | AFP | CD30 | OCT-4 | CD117 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yolk sac tumor | + | ± | ± | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Dysgerminoma | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Embryonal carcinoma | + | − | − | + | − | ± | + | + | − |

Given the rarity of primary endometrial YSTs, there is no consensus on the treatment of this extremely rare tumor. Surgery combined with adjuvant chemotherapy is the main reported treatment. Most patients undergo TAH BSO treatment, except for one patient with unilateral ovary reservation and two with bilateral ovary reservation.11,18 The patients with bilateral ovary reservation were a 30-year-old woman (stage II) 11 and a 27-year-old woman (stage IA), 18 who survived for more than 6 years and 14 months, respectively. A 29-year-old woman in stage II in whom the right adnexa was preserved was alive without recurrence for 39 months. 12 These data demonstrate the possibility of ovary reservation for young patients with early-stage primary YST of the endometrium, retaining ovarian endocrine function and improving quality of life.

Of 30 cases, compared with those combined with somatic tumor (5/13, 38.5%), pure endometrial YSTs were more likely in an early stage (12/17, 70.6%) though no statistical difference was detected (P = 0.082). The OS and DES were slightly longer in pure endometrial YSTs than in somatic tumor, but with no statistical differences (mean OS: 48.1 vs 21.9 months, P = 0.690; mean DFS: 53.0 vs 20.7 months, P = 0.485). These findings suggest that patients with endometrial YST combined with somatic tumor tend to be at a slightly higher stage and have a poor prognosis.

Conclusion

Primary YST of the endometrium, a highly malignant germ cell tumor, is extremely rare. Surgery combined with postoperative chemotherapy is considered effective for the treatment of primary endometrial YST. Ovarian conservation is optional in young patients. Patients with pure YST are younger than those with concomitant somatic tumors. Patients with endometrial YST combined with somatic tumor tend to be at a slightly higher stage and have a poor prognosis. However, additional cases need to be further analyzed for a better understanding of these rare tumors.

Footnotes

Author contribution: R.B. provided the case and critically revised the manuscript. H.G. was responsible for the acquisition and interpretation of patient data and manuscript preparation. R.B. and H.G. performed pathological examination. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Facility Ethical Committee (Fudan University Cancer Center Ethics Committee, China; approval no. 050432-4-121B, 13 December 2012).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the National Natural Foundation Science of China (grant no. NSFC 81802597).

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Huijuan Ge  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1059-4212

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1059-4212

Referrences

- 1. Ulbright TM. Germ cell tumors of the gonads: a selective review emphasizing problems in differential diagnosis newly appreciated controversial issues. Mod Pathol 2005; 18: S61–S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spatz A, Bouron D, Pautier P, et al. Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 1998; 31(2): 285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pileri S, Martinelli G, Serra L, et al. Endodermal sinus tumor arising in the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol 1980; 56(3): 391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ravishankar S, Malpica A, Ramalingam P, et al. Yolk sac tumor in extragonadal pelvic sites: still a diagnostic challenge. Am J Surg Pathol 2017; 41(1): 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mutch DG, Prat J. 2014. FIGO staging for ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2014; 133(3): 401–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ohta M, Sakakibara K, Mizuno Kano T, et al. Successful treatment of primary endodermal sinus tumor of the endometrium. Gynecol Oncol 1988; 31(2): 357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Magers MJ, Kao CS, Cole CD, et al. “Somatic-type” malignancies arising from testicular germ cell tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 124 cases with emphasis on glandular tumors supporting frequent yolk sac tumor origin. Am J Surg Pathol 2014; 38(10): 1396–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patsner B. Primary endodermal sinus tumor of the endometrium presenting as “recurrent” endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2001; 80(1): 93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oguri H, Sumitomo R, Maeda N, et al. Primary yolk sac tumor concomitant with carcinosarcoma originating from the endometrium: case report. Gynecol Oncol 2006; 103(1): 368–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Joseph MG, Fellows FG, Hearn SA. Primary endodermal sinus tumor of the endometrium: a clinicopathologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer 1990; 65(2): 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rossi R, Stacchiotti D, Bernardini MG, et al. Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204(4): e3–e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang C, Li G, Xi L, et al. Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011; 114(3): 291–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ji M, Lu Y, Guo L, et al. Endometrial carcinoma with yolk sac tumor-like differentiation and elevated serum beta-hCG: a case report and literature review. Onco Targets Ther 2013; 6: 1515–1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abhilasha N, Bafna UD, Pallavi VR, et al. Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium: a rare entity. Indian J Cancer 2014; 51(4): 446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qzler A, Dogan S, Mamedbeyli G, et al. Primary yolk sac tumor of endometrium: report of two cases and review of literature. J Exp Ther Oncol 2015; 11(1): 5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Damato S, Haldar K, McCluggage WG. Primary endometrial yolk sac tumor with endodermal-intestinal differentiation masquerading as metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2016; 35(4): 316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shokeir MO, Noel SM, Clement PB. Malignant Mullerian mixed tumor of the uterus with a prominent alpha-fetoprotein-producing component of yolk sac tumor. Mod Pathol 1996; 9(6): 647–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lu T, Qi Ma Y, Lu G, et al. Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium: a case report and review of the literatures. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019; 300(5): 1177–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song L, Wei X, Wang D, et al. Primary yolk sac tumor originating from the endometrium: a case report and literature review. Medicine 2019; 98(15): e15144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin SW, Hsieh SW, Huang SH, et al. Yolk sac tumor of endometrium: a case report and literature review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2019; 58(6): 846–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nogales FF, Preda O, Nicolae A. Yolk sac tumours revisited. Histopathology 2012; 60(7): 1023–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rutgers JL, Young RH, Scully RE. Ovarian yolk sac tumor arising from an endometrioid carcinoma. Human Pathology 1987; 18(12): 1296–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nogales FF, Bergeron C, Carvia RE, et al. Ovarian endometrioid tumors with yolk sac tumor component, an unusual form of ovarian neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20(9): 1056–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McNamee T, Damato S, McCluggage WG. Yolk sac tumours of the female genital tract in older adults derive commonly from somatic epithelial neoplasms: somatically derived yolk sac tumours. Histopathology 2016; 69(5): 739–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kao CS, Idrees MT, Young RH, et al. Solid pattern yolk sac tumor: a morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 52 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36(3): 360–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rougemont AL, Tille JC. Role of HNF1beta in the differential diagnosis from other germ cell tumors. Hum Pathol 2018; 81: 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cao D, Guo S, Allan RW, et al. SALL4 is a novel sensitive and specific marker of ovarian primitive germ cell tumors and is particularly useful in distinguishing yolk sac tumor from clear cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33(6): 894–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]