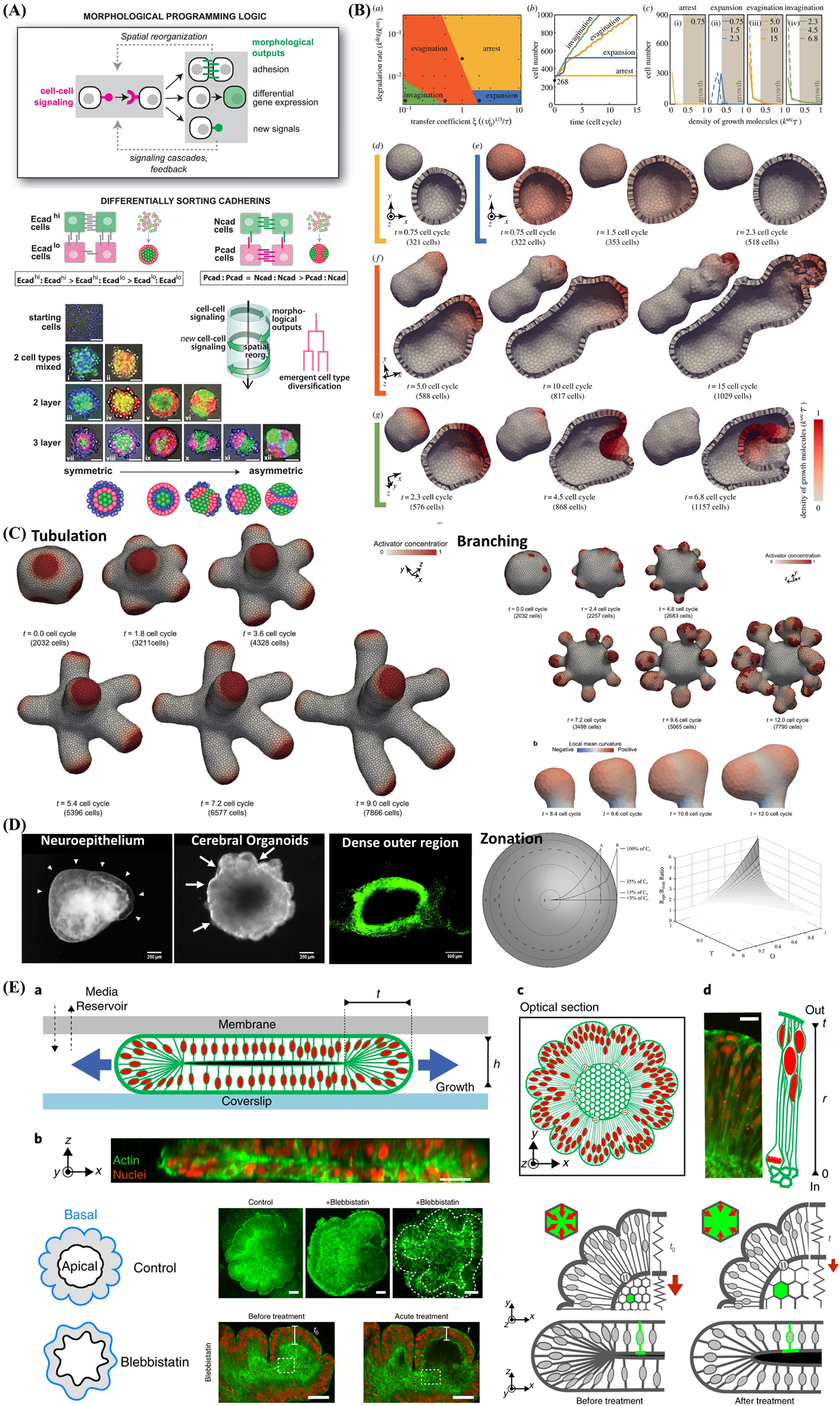

Figure 7.

Computational simulation and mathematical modeling of complex behavior arising in multicellular constructs and self-assembled organoids from iPSC. A) Engineering cell–cell communication and signaling networks within self-organizing multicellular structures and organoids to program synthetic morphogenesis with spherically asymmetric structures by inducing differentially sorting adhesion molecules and using the simple synNotch→adhesion toolkit. Reproduced with permission.[272] Copyright 2021, American Association for the Advancement of Science. B) Computational simulations of signal-dependent epithelial growth and deformation during tissue morphogenesis that be categorized into four phases: arrest (yellow), expansion (blue), evagination (orange), and invagination (green). Reproduced with permission.[278] Copyright 2015, Royal Society. C) Combining Turing and 3D vertex models reproduces autonomous multicellular morphogenesis with undulation, tabulation (time series images of thin tube formation), and branching(time series images of whole tissue deformation and branch structure). Reproduced with permission,[279] Copyright 2018, Springer Nature. D) Analytic models of oxygen and nutrient diffusion, metabolism dynamics, and architecture optimization in a multicompartment spherical model for cerebral organoids with metabolically active region, intermediate region, hypoxic region, and ischemic region, respectively. Reproduced with permission.[280] Copyright 2016, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. E) Brain organoid development and wrinkling occurs at a critical nuclear density and maximal strain. Nuclear motion and swelling during cell cycle lead to differential growth. Cytoskeletal forces maintain organoid core contraction and stiffness and adding cytoskeleton inhibition (blebbistatin) show the reduction in thickness and increase in inner surface area. Reproduced with permission.[283] Copyright 2018, Springer Nature.