Abstract

Lemierre syndrome (LS) is an acute oropharyngeal infection with secondary septic thrombophlebitis and distant septic embolisation. A 29-year-old woman with sore throat, dyspnoea and left shoulder pain, who was on levofloxacin for 3 days, presented with worsening symptoms. She was tachycardic, tachypneic and hypoxic on presentation. CT of neck and chest revealed multiple loculated abscesses on her left lower neck and shoulder, right peritonsillar abscess, thrombosis of the right external jugular vein and multiple bilateral septic emboli to the lungs. She was started on clindamycin and ampicillin sulbactam for LS. She developed septic shock and required intubation due to respiratory failure. Drainage of the left shoulder abscess grew Fusobacterium nucleatum. After 2 weeks of a complicated intensive care unit stay, her haemodynamic status improved and she was transferred to the floor. LS has variable presentations, but regardless of the presentation, it is a potentially fatal disease-requiring prompt diagnosis and management.

Keywords: ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology, infectious diseases, adult intensive care, pleural infection, pulmonary embolism

Background

Lemierre syndrome (LS), also known as necrobacillosis or postanginal septicemia, is characterised by septic thrombophlebitis, bacteremia and metastatic septic emboli secondary to acute pharyngeal infections.1 2 LS is mainly preceded by recent viral or bacterial upper respiratory syndrome, which leads to weakened mucosa and easy invasion of the oropharyngeal pathogens.3 4 It predominantly affects teenagers and young adults aged 14–24.1 There is male sexual predominance with 2:1.1 Epidemiologically, LS is a very rare condition, with a reported annual incidence of around three cases per million.1 5 6 Before antibiotics were broadly available, this disease was quickly progressive, and often fatal.7 After antibiotic availability and use became widespread, the disease has become a rare entity, and, hence, is often referred to as ‘the forgotten disease’.8 We are reporting this rare, forgotten disease in a patient who presented with a shoulder abscess in this era of wide antibiotic availability.

Case presentation

A 29-year-old woman with a previous medical history of asthma and polycystic ovary syndrome presented to our hospital with reports of a sore throat, fever and left shoulder pain for 1 week and shortness of breath for 2 days. Two weeks prior to admission, she had a bout of runny nose and nasal congestion, which was then followed by sore throat, subjective fever, fatigue, malaise and chills. She reported that her sore throat was associated to difficulty swallowing solids while her shoulder pain was associated to noticing a lump in the left shoulder and lower neck. Her shoulder pain was constant, dull, nonradiating and was associated with no aggravating or relieving factors. Three days prior to this presentation, she was seen in an urgent care facility, where she was prescribed levofloxacin. Her symptoms were progressively worsening despite being report to levofloxacin. Her exposure history was significant in her husband, and son were sick with symptoms of an upper respiratory infection a week before her symptoms began.

On initial presentation, she was found to be hypoxemic; hence, she was started on oxygen via nasal cannula at a rate of 3 L/min. She was found to be febrile with a body temperature of 39.4°C and was also tachycardic (heart rate of 110 bpm) and tachypneic (respiratory rate of 30 bpm). Her blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg. On examination, she appeared anxious and was in respiratory distress. Her neck was exquisitely tender to palpation. An oral examination demonstrated right peritonsillar abscess. A cardiopulmonary examination was significant for tachycardic rate and bilateral bibasilar rales. Red, hot and tender swelling at her left shoulder and left lower neck was visualised, which led to impaired range of motion in her left upper extremity.

Investigations

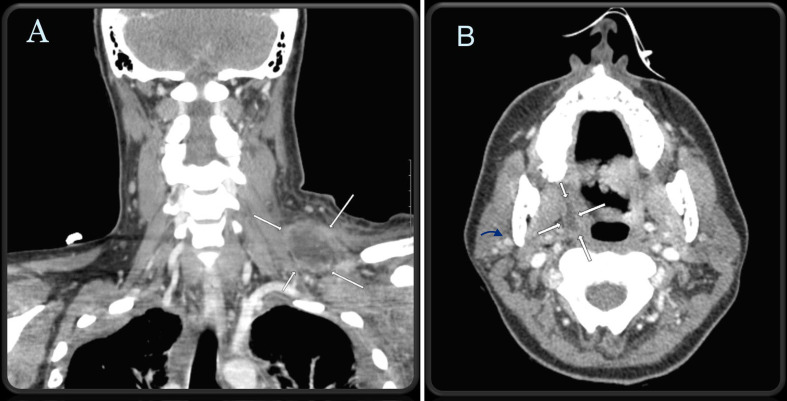

Initial blood work revealed leucocytosis with a white cell count of 32.0×109/L, with a left-sided shift and an absolute neutrophil count of 29 000/ μL. Due to her acute shortness of breath, a CT scan of her chest was done, which showed that she had indurated, edematous changes in soft tissue/musculature of the left chest, multiple scattered nodularities, suspicious of septic emboli in both of her lungs and a mild loculated bilateral pleural effusion (figure 1). No obvious pulmonary embolus was reported. Given her typical history of persistent sore throat leading to septic emboli, a bedside point-of-care ultrasound (US) of her neck was done, which did not reveal any thrombus formation in the internal jugular veins of her neck. A CT scan of her neck was done, which showed patent bilateral internal jugular veins, 1.6 ×0.6 cm right peritonsillar abscess, a small thrombus in a branch of right external jugular vein and a 7 cm-thick-walled loculated fluid collection in the left lower neck/left shoulder, concerning for abscess. (figure 2) A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was done, which showed no vegetations with a normal ejection fraction.

Figure 1.

CT scan of the chest with contrast illustrates multiple scattered nodularities suspicious of septic emboli in both lungs and a mild loculated bilateral pleural effusion.

Figure 2.

CT soft tissue of the neck with intravenous contrast. (A) Extensive and severe soft tissue swelling at left lateral neck base with a 7 cm thick-walled loculated fluid collection concerning for abscess demonstrated by white arrows. (B) Transverse view of soft tissue neck demonstrates patent bilateral internal jugular veins with a 1.6 cm x 0.6 cm right peritonsillar abscess (demonstrated by white arrows) and thrombosed right external jugular vein (demonstrated by blue arrow).

Differential diagnosis

CT chest showed no focal consolidations ruling out community-acquired pneumonia. CT soft tissue neck showed no dental, submandibular, sublingual or submental abscesses, ruling out Ludwig’s angina. Epiglottitis was also ruled out based on CT soft tissue neck findings. TTE showed no vegetations, which made endocarditis less likely. Ultimately, LS was diagnosed with presence of septic thrombophlebitis of the external jugular vein, growth of Fusobacterium nucleatum (FN) on abscess cultures and metastatic septic pulmonary emboli secondary to acute pharyngeal infection.

Treatment

Due to her worsening respiratory and haemodynamic status, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and she was empirically started on vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam on admission. General surgery and infectious diseases were consulted and the patient’s antibiotics were changed to ampicillin/sulbactam and clindamycin. The patient became more tachypneic, hypotensive and hypoxic. She had to be intubated and was started on vasopressors. General surgery was able to drain the left lateral neck base abscess—subsequent culture results showed growth of FN. Antibiotic sensitivities were not available. Initial decision to start the combination of beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitor was based on the reports of resistance to beta-lactams in Fusobacterium.

Over the next few days, the patient had worsening of her pleural effusions and bilateral chest tubes had to be placed. Pleural fluid cultures were obtained and showed growth of FN. Due to minimal output from the chest tubes, thoracic surgery was consulted, and the patient needed a thoracotomy with left-sided and right-sided open decortication. She eventually started to improve. She was weaned off the vasopressors and was subsequently extubated. She remained in the ICU for 14 days and was transferred out to the floor.

Outcome and follow-up

Ampicillin/sulbactam and clindamycin were continued for the patient until her clinical improvement. Later, antibiotics were de-escalated to ampicillin/sulbactam to complete the 4-week course. She needed inpatient rehabilitation initially and was eventually able to go home. She was followed up by her primary care provider 3 months later and she reported no persistent symptoms.

Discussion

LS was originally described in 1936 by the French microbiologist André Lemierre. Historically, the name has been used to describe a severe septicemic state caused by FN originating from oropharynx infections at the level of the palatine tonsils, and it was associated with ipsilateral thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein and septic emboli, most commonly to the lungs.2 9 10 However, there is no firmly established consensus on the definition of LS; a broader spectrum of clinical presentations has been reported. Typical LS commonly causes internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis after an oropharyngeal infection due to Fusobacterium sp, which accounts for nearly 50% of the LS cases.2 10 The initial infection can come from other anatomic regions of the craniofacial region, such as sinusitis, pharyngitis, mastoiditis and even tooth infections.2 11 Infectious foci outside the head and neck have also been reported in atypical or variant LS.10

Although internal jugular vein involvement is more common, usually unilateral and ipsilateral to the source of infection, multiple other vessels can be involved, including bilateral internal jugular veins, external jugular veins, the cavernous sinus and intracranial veins.2 11 12 The patient presented in this case had thrombosis of the right external jugular vein, which is a less common vessel to be involved, affecting only 6.0%–6.7% of the patients with thrombotic events.2 12

In terms of septic emboli, the lungs are the most commonly affected organs, being found in over a third of the cases; however, brain emboli have also been reported.12 This case was also unusual, in that, in addition to septic emboli to both lungs, a lower neck soft tissue abscess was also present. Soft tissue has been reported as the site of metastatic spread, although this is less common. According to a literature review by Bird et al, soft tissue infections were responsible for 9% of metastatic emboli, of which 70% were associated with concomitant pulmonary disease.13

Furthermore, septic embolisation to lungs in LS can be complicated by the development of empyema, which is reported in 17%–27% cases.14 15 Development of empyema in LS requires drainage with chest tubes or minimally invasive video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS).15 16 Due to minimal output via chest tubes, our patient underwent bilateral decortication, which is reported in a handful of case reports.

Blood cultures are required to identify the offending organism. FN is the most common causing agent, being reported in 33%–57% of the cases.8 11 17 Other organisms have been implied as the culprit for LS, including other Fusobacterium sp (FN and F. mortiferum), Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus; in a significant number of cases, cultures do not grow any organisms.2 8 17 In some instances, the pathogen can also be isolated from pleural fluid, CSF or abscess collection cultures. Because FN’s incubation period is long, and negative cultures do not rule out the presence of FN, if clinical suspicion for LS is high, adjustment of the antibiotic regimen to include coverage for FN should not be delayed. In a recent retrospective study by Afra et al, FN was seen more commonly in the younger population without comorbidities and was associated with increased virulence, while FN was isolated from older populations with malignancies or on dialysis.18

Recommended antibiotic regimens should include coverage for anaerobic organisms. Multiple combinations of drugs have been reported. Acceptable choices of classes include beta-lactams/beta-lactamase inhibitors such as piperacillin/tazobactam, metronidazole or clindamycin. Cephalosporins and fluroquinolones are less favoured.1 8 Despite an appropriate antibiotic treatment, one in seven develop new or recurrent thromboembolism and/or a new peripheral septic lesion.2 Nine to ten per cent of LS survivors develop serious long-term complications, including neurologic deficits and debilitating conditions including cranial nerve palsy, blindness or reduced visual acuity, paralysis or orthopaedic or functional limitation.2 Our patient also required a month of intensive rehabilitation before being discharged home.

The role of anticoagulant use for LS has long been debated. A retrospective study by Cupit-Link et al found no differences between an anticoagulated LS patient group verus a nonanticoagulated LS patient group in terms of thrombus resolution, recurrent thrombosis or progression of thrombosis during the follow-up.19 Nygren et al also found no significant differences in outcomes between patients with jugular vein thrombosis exposed to therapeutic, prophylactic and no anticoagulation therapy.20 However, Schulman and Valerio et al confirmed the favourable prognosis in patients receiving anticoagulation in terms of recurrent thrombosis, particularly those who received it before peripheral (lungs, joints and spine) and central nervous system involvement.2 21 Analysis by Valerio et al also noticed an increased risk of major bleeding in patients who underwent invasive procedures, but no differences with respect to bleeding in both the anticoagulated and nonanticoagulated groups. Our patient was receiving a prophylactic dose of heparin for deep venous thrombosis. A full dose was not given because of the requirement of multiple invasive procedures throughout the hospitalisation. To date, there is no common consensus regarding the usage of anticoagulation therapy in LS. However, the majority of the literature strongly advocates for weighing the risks and benefits of providing anticoagulation against the potential of bleeding complications.20 The literature also suggests using anticoagulation particularly in patients with thrombus progression into the cavernous sinus or central nervous system or nonresolution of thrombus despite antibiotic use and/or identification of a hypercoagulable state.19

Multiple imaging modalities have been used to assist in the diagnosis of LS. US imaging has the advantage of being inexpensive and readily available and is helpful in identifying thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein without exposing the patient to ionising radiation or iodinated contrast. On the other hand, US is unable to identify the underlying infectious process and visualisation of the vessels adjacent to the clavicle, and mandibles is suboptimal. It also has a low sensitivity to identify newly formed thromboses, as they have low echogenicity.22–24 High-resolution CT is the modality of choice for accurate demonstration of pathologic phenomena present in LS. It allows identification of thrombi in deeper vessels, whereas US imaging might be challenging. It is also able to show septic emboli in the lungs and other areas. Finally, its ability to demonstrate local complications in the neck, such as abscesses, is another advantage of contrast-enhanced CT.17 22 23 MRI is an excellent study to identify intraluminal thrombi and soft tissue abnormalities, but its high cost and decreased availability lead to CT being favoured.8 17

This case report brings attention to the uncommon presentations of LS. Diagnosis of this still rare clinical entity requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and attention to aspects of the patient’s history and physical examination. Point-of-care US can be a potential ally for the early identification of neck vein thrombosis; however, in this case, US alone was unable to diagnose the external jugular vein thrombus, and CT of the neck was required to establish a diagnosis. Diagnosing this condition in a timely fashion is crucial, as many empiric antibiotic regimens do not provide coverage for the anaerobic organism most commonly causing this disease. With inadequate treatment, LS can rapidly progress to clinical status deterioration and potentially death. A multidisciplinary team is required to provide adequate care for patients with this condition.

Learning points.

Historically, Lemierre syndrome (LS) was associated to septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein. But current practice for diagnosis of LS does not require internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis rather to accept thrombophlebitis in similar district. In our case, external jugular vein was involved.

CT scan is the modality of choice for accurate demonstration of thrombophlebitis in LS as it can identify thrombi in deeper vessels that may be missed by ultrasound (US) imaging.

LS commonly causes septic pulmonary embolisation. Our patient had soft tissue abscesses in addition to pulmonary involvement, which is reported in 9% of cases.

Although Fusobacterium necrophorum is the most commonly reported cause of LS, other pathogens including F. nucleatum can also precipitate in this syndrome.

Despite initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment for LS, the patient’s clinical condition can worsen due to new or recurrent thromboembolism and/or new septic lesions requiring multidisciplinary team involvement.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the supervision provided by Dr. Benjamin S. Avner. He reviewed the final manuscript and provided critical feedback. He also provided insight into his experience in treating Lemierre’s syndrome.

Footnotes

Contributors: DK updated and revised the manuscript. WES and TG wrote the first manuscript and collected the literature. FNUW reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Lee W-S, Jean S-S, Chen F-L, et al. Lemierre's syndrome: a forgotten and re-emerging infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2020;53:513–7. 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valerio L, Zane F, Sacco C, et al. Patients with Lemierre syndrome have a high risk of new thromboembolic complications, clinical sequelae and death: an analysis of 712 cases. J Intern Med 2021;289:325–39. 10.1111/joim.13114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan ZL, Nagaraja TG, Chengappa MM. Biochemical and biological characterization of ruminal Fusobacterium necrophorum. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1994;120:81–6. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes CE, Spear RK, Shinabarger CE, et al. Septic pulmonary emboli complicating mastoiditis: Lemierre's syndrome revisited. Clin Infect Dis 1994;18:633–5. 10.1093/clinids/18.4.633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuppalli K, Livorsi D, Talati NJ, et al. Lemierre's syndrome due to Fusobacterium necrophorum. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:808–15. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70089-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osowicki J, Kapur S, Phuong LK, et al. The long shadow of Lemierre's syndrome. J Infect 2017;74(Suppl 1):S47–53. 10.1016/S0163-4453(17)30191-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagelskjaer Kristensen L, Prag J. Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre's syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:524–32. 10.1086/313970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karkos PD, Asrani S, Karkos CD, et al. Lemierre's syndrome: a systematic review. Laryngoscope 2009;119:1552–9. 10.1002/lary.20542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemierre A. On certain SEPTICÆMIAS due to anaerobic organisms. The Lancet 1936;227:701–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)57035-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valerio L, Corsi G, Sebastian T, et al. Lemierre syndrome: current evidence and rationale of the Bacteria-Associated thrombosis, thrombophlebitis and Lemierre syndrome (battle) registry. Thromb Res 2020;196:494–9. 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong AW, Spooner K, Sanders JW. Lemierre's syndrome. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2000;2:168–73. 10.1007/s11908-000-0030-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gore MR. Lemierre syndrome: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2020;24:379–85. 10.1055/s-0039-3402433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bird NT, Cocker D, Cullis P, et al. Lemierre's disease: a case with bilateral iliopsoas abscesses and a literature review. World J Emerg Surg 2014;9:38. 10.1186/1749-7922-9-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal SK, Nath A, Singh R, et al. Lemierre's syndrome presenting with neurological and pulmonary symptoms: case report and review of the literature. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2013;16:259–63. 10.4103/0972-2327.112489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croft DP, Philippo SM, Prasad P. A case of Lemierre's syndrome with septic shock and complicated parapneumonic effusions requiring intrapleural fibrinolysis. Respir Med Case Rep 2015;16:86–8. 10.1016/j.rmcr.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jalota L, Gupta S, Mainali N. Lemierre’s syndrome causing cavitary pulmonary disease. J Pulm Med 2013;15:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johannesen KM, Bodtger U. Lemierre's syndrome: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. Infect Drug Resist 2016;9:221–7. 10.2147/IDR.S95050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afra K, Laupland K, Leal J, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of Fusobacterium species bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:264. 10.1186/1471-2334-13-264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cupit-Link MC, Nageswara Rao A, Warad DM, et al. Lemierre syndrome: a retrospective study of the role of anticoagulation and thrombosis outcomes. Acta Haematol 2017;137:59–65. 10.1159/000452855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nygren D, Elf J, Torisson G, et al. Jugular Vein Thrombosis and Anticoagulation Therapy in Lemierre's Syndrome-A Post Hoc Observational and Population-Based Study of 82 Patients. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021;8:ofaa585. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulman S. Lemierre syndrome - treat with antibiotics, anticoagulants or both? J Intern Med 2021;289:437–8. 10.1111/joim.13100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim BY, Yoon DY, Kim HC, et al. Thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein (Lemierre syndrome): clinical and CT findings. Acta Radiol 2013;54:622–7. 10.1177/0284185113481019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gudinchet F, Maeder P, Neveceral P, et al. Lemierre's syndrome in children: high-resolution CT and color Doppler sonography patterns. Chest 1997;112:271–3. 10.1378/chest.112.1.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ungprasert P, Srivali N. Diagnosis and treatment of Lemierre syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:1319. 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]