Abstract

Background

Caring for a person with dementia predisposes informal carers (carers) to mental and physical disability. Carers tend to focus on the needs of the person with dementia and have difficulties expressing their own needs for support. No instrument has yet been developed to directly assess carers’ support needs. The aim of this study is to clarify the main categories of carers’ support needs to inform future development of an instrument to assess carers’ support needs.

Methods

A qualitative approach combining focus group interviews with carers and professionals and individual interviews were used.

Results

Carers’ support needs were categorised into four areas: (i) daily life when caring for a person with dementia, (ii) focus on themselves, (iii) maintain own well‐being, and (iv) communicate and interact with surroundings.

Discussion

Carers have support needs in common regardless of the relation to the person with dementia. Carers tend to focus on the needs of the person with dementia, thus not knowing their own needs. The four main categories clarified in this study may inform the foundation of developing an instrument to facilitate dialogue between carers and professionals with the purpose of assessing carers’ support needs.

Keywords: dementia, Alzheimer’s, carer, caregiver, needs assessment, support needs, service needs and interview

Introduction

An informal carer (carer) is any person who helps a partner, family member, or friend and in need of personal and/or practical assistance motivated by the personal relation rather than financial compensation (1). A consequence to the ageing populations in many countries (2) is an increasing number of persons with dementia. In Denmark, approximately 85.000 people have dementia, while approximately 400.000 carers are influenced by the consequences of caring (3, 4). Dementia carers experience more physical, emotional and economic stressors, are more likely to experience mental and physical disability themselves and have higher risk of mortality compared to carers of patients with other types of chronic illness (5, 6). Carers tend to neglect their own well‐being and often report that supervising the person with dementia and managing the cognitive impairment and behavioural problems are challenging stressors (7). These stressors may amplify because the person with dementia is less likely to express gratitude for the help they receive (5). In addition, stress often intensifies over time, as carers often provide care for many years (2). Meaney et al. showed that carers of a person with dementia exhibit high levels of unmet needs and low levels of service use (8). Therefore, action is needed, and using a validated instrument to assess carers’ support needs may constitute a standardised way of assessing carers’ needs for support (9) to improve their well‐being and reduce their risk of disability, thereby also facilitating the well‐being of the person with dementia (10).

To our knowledge, no robust instrument has been published that directly assesses carers’ support needs for use in a healthcare and social care setting (11). Most existing instruments focus on measuring the impact of carer burden with no indication of what carers consider important to meet their own support needs (10, 12). Also, existing needs assessment instruments are not developed as self‐reported measures for use in health and social care with the primary purpose of uncovering carers’ support needs (13, 14). Consequently, there is a need for a feasible self‐reported instrument to guide assessment of carers’ support needs (11, 15). Such an instrument may assist professionals in offering purposeful and relevant supportive interventions to carers (2, 16).

A self‐reported standardised instrument also offers assessment of support needs without professional prejudice (17). Carers and professionals have different perspectives of carers’ support needs (11), with professionals focusing on needs in relation to the care of the person with dementia and thus not always acknowledging the carers other needs (18). Further, carers tend to focus on the person with dementia’s needs for care and have difficulties expressing their own needs (19, 20); thus, other ways to recognise carers support needs are needed. Some studies have already investigated carers’ needs (20, 21, 22). However, these studies have a narrow focus on support needs in relation to disease severity of the person cared for. When identifying carers’ individual support needs, a more appropriate approach may instead depend on the relationship to the person with dementia (23), and carers own experience of phases due to the challenges of adapting to changes throughout the progression of dementia (24). Allowing a broader focus, a framework to understand different expressions of support needs is defined by four types of needs: felt, normative, comparative and expressed needs (19). A ‘felt’ need is the carer’s actual need for support. ‘Normative’ and ‘comparative’ needs are based on professional knowledge and the public opinion. ‘Expressed' needs are what carers are able to articulate, and in practice, a lack of translation is seen between the different expressions of carers’ needs for support (19). When assessing carers’ support needs, it is therefore important to incorporate both carers’ and professionals’ perspectives to get a complete understanding of this abstract phenomenon (25). Furthermore, needs should be assessed regularly because needs in general change over time and carers’ needs may change because of the progression of the condition (10, 18).

Several studies describe the experience of caring for a person with dementia (20, 26, 27, 28). In common, carers experience substantial changes in the relationship to the person with dementia (20, 28) which calls for carers to manage new roles (27, 29) and sets high expectations on how to adapt and adjust in daily life when caring for a person with dementia (24). Although few studies have directly investigated carers’ support needs as the primary study objective, a systematic review of carers needs shows that carers in general need information on how to provide the best care and how to manage their own physical and emotional health (20). Though a variety of supporting interventions exists such as home care, respite care, group‐based psychological education and communication skills training (30), carers experience that these do not entirely meet their support needs (11). This points to the lack of concurrence between carers support needs and supportive services, which may be explained by a complex interaction between carers’ needs and the carers’ whole life situation, including the needs of the person with dementia (20).

To embrace this complex interaction, the biopsychosocial model offers a dynamic and holistic theoretical approach to perceive carers’ support needs (31). The model defines health as the ‘state of total biological, social and emotional well‐being’ (32). It allows for professionals within social and health care to acknowledge the multidimensional support needs of carers (11) not related to a diagnoses but to the subjective experience of well‐being (33). In this model, the carer’s well‐being is a result of an interaction between physical, emotional and social components including contextual factors such as the person with dementia’s health and well‐being (31), and needs for supportive services arise in this dynamic interaction. Adapting this theoretical approach thus allows for identification of both biomedical and psychosocial support needs due to changes in relation to the person with dementia, and contains both positive and negative aspects of caring (34).

The aim of this study is to clarify main categories of carers’ support needs when caring for a person with dementia in order to inform a foundation for the development of a multidimensional instrument to assess carers’ support needs that may facilitate the dialogue between carers and professionals in every day social and health care.

Methods

Design

This qualitative study used focus group interviews with first professionals and then carers to explore main characteristics and personal perspectives on carers’ support needs (35, 36). We then conducted individual interviews with carers, to pursue the meaning of the personal and sensitive experiences of support needs (37). A combination of qualitative data collection is suitable when developing a nuanced understanding of carers’ support needs, because it allows for contribution of overlapping and complementary findings and therefore a wider exploration of the phenomenon (38, 39). However, qualitative investigation alone is not enough to inform development of an assessment instrument, and this study were therefore part of a greater development process (40).

Participants

To comply with the inclusive definition of carers in this study, a strategy of purposive sampling was conducted in two municipalities in Denmark to achieve maximum variation among participants regarding gender, cohabitation, progression of dementia and relation to the person with dementia (see Table 1 for inclusion criteria) (41). Evaluation of progression of dementia was based on carers subjective assessment of the person cared for following the criteria from the Danish Health Authority (mild, moderate and severe) (42). Heterogeneity in participants were strived for to get as nuanced description of the abstract concept of carers’ support needs considering that support needs may be hard to express and emerge in different ways (19). Key professionals in each municipality led recruitment to promote a heterogeneous group of participants. Due to their familiarity with carers in the municipality, the key professionals were in a unique position to approach carers who might not have otherwise volunteered because of lack of initiative to commit in research.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for participants in interviews

| Interview type | Number of participants | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Focus group interviews, professionals | 13 | Working in dementia social care or health care |

| Focus group interviews, carers | 18 | ≥18 years, provides help on a regular basis because of a personal relationship rather than financial compensation to a closely related person who has received a dementia diagnosis, able to communicate in Danish |

| Individual interview, carers | 5 |

Data collection

Focus groups

Firstly, we held two focus group interviews with professionals to explore carers’ support needs as observed by professionals. Secondly, we held three focus group interviews with carers to explore their various support needs in the past and present. Data collection was an iterative process, and carers were allowed to reflect upon the professional perspective on carers’ support needs to validate their relevance. Using focus groups allowed dialogue between people in the same situation and facilitated the rethinking and discovery of unexpected perspectives of carers’ support needs (35). Each focus group had four to eight participants to enable a group dynamic where everyone was able to express their views (43). The professionals in each focus group came from the same municipality but had different professional backgrounds and experience with dementia care. Participants in the carer groups were assembled based on cohabitation and relation to the person with dementia in each municipality (35).

Individual interviews

Five individual semi‐structured interviews with carers were conducted. Striving for including different types of carers, participants were sampled to complement participants in the focus groups (43).

Interview guide

We developed an interview guide to enable consistency in interviews and to comply with the different contexts of interviews (35). The guide was organised in terms of participants presented their situations as well as described and discussed their support needs. To facilitate discussion, we introduced text cards that described areas of carers’ support needs. Using such an activity should elicit participants less comfortable in the situation or those who needed extra time to express their thoughts (44). Examples of topics in the text card were’Financial issues – I need help to manage financial tasks’ and ‘Worrying – I need help to manage changes in daily life’. Participants were asked to discuss the cards expressing their most important support needs. Participants were also encouraged to add topics not represented in the cards. A systematic search of the literature including keywords such as ‘dementia’, ‘caregiver’ and ‘support needs’ guided the development of text cards. Topics for discussion were derived through an extensive work of inductive content analysis (38) of support needs identified in the literature (10, 20, 45) resulting in 16 sub‐categories written on the cards.

Settings

Two‐hour focus group interviews were hosted at a local meeting facility. Individual interviews lasted one hour and were hosted in the participants’ homes. All interviews were conducted by the first author with the assistance of an experienced co‐moderator in the focus group interviews (35). All interviews were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analyses

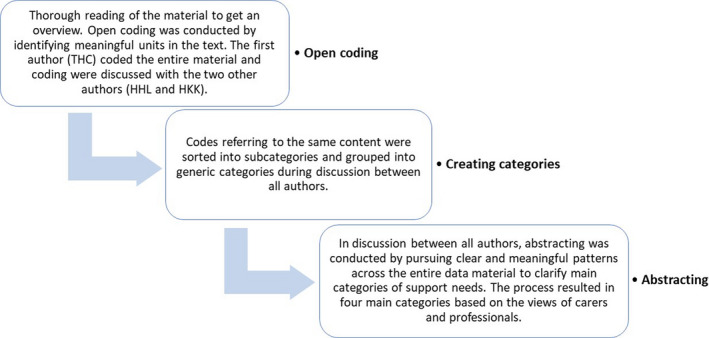

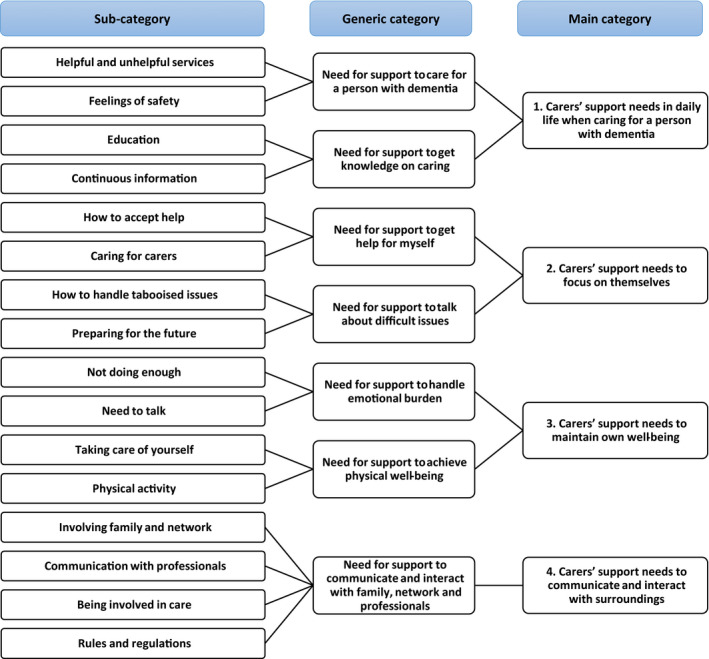

Data were analysed with an inductive qualitative content analysis approach (38, 46) where data were grouped into categories to describe the manifest content (47). Coding was done in NVIVO 11 (http://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo‐products/nvivo‐11‐for‐windows). Content analysis of data involved three stages: open coding, creating categories and abstracting, as described in Fig. 1. The first stage started with a thorough reading of the material where after meaningful units in the text were coded. In the second stage, codes referring to the same content were grouped into sub‐categories; thus, the different perspectives of carers and professionals were integrated by looking for understandings in common. Lastly, abstraction of sub‐ and generic categories was conducted in discussion between all authors and meaningful patterns were pursued across the material, resulting in four main categories that provide an overall description of carers’ support needs including both perspectives. The seven generic and four main categories are presented in Fig. 2. Also, Table 2 shows examples of the abstraction process directly linking the meaningful units to sub‐, generic, and main categories.

Figure 1.

Description of the three stages in the content analysis process

Figure 2.

Coding tree presenting main, generic and sub‐categories derived through the inductive content analysis process

Table 2.

Examples of the inductive content analysis showing the process from codes to categorisation

| Meaningful unit | Code | Sub‐category | Generic category | Main category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'Anyway, regarding the practical issues of caring, I am quite good at dealing with what has to be done' (Friend P2) | Practical help | Helpful and unhelpful services | Need for support to care for a person with dementia | 1. Carers’ support needs in daily life when caring for a person with dementia |

| 'You have to be careful not to take something away from them that they would have liked to do themselves'. (Professional P26) | ||||

| 'Then I know she has been interacting with someone and has been stimulated…and really has had her need for company met'. (Daughter P4) | Activities for the person with dementia | |||

| 'Now she only lives one and a half kilometres from me, which is easy…but…before she lived seventeen kilometres away and …sometimes…well, things happened and then the next. And she was so sad. And then I had to go all this…way just to find out it was nothing special…'. (Daughter P4) | Being vigilant | Feelings of safety | ||

| 'Many carers express that they focus on all of those nice experiences together and they often find it hard to organise themselves'. (Professional P30) | Initiating nice experiences | Not doing enough | Need for support to handle emotional burden | 3. Carers’ support needs to maintain own well‐being |

| 'I told him as it was, even though it was harsh. A friend’s wife got the Alzheimer’s disease two years after my wife. It was my damn luck. Now we have each other to talk to'. (Husband P20) | Contact with others in the same situation | Need to talk |

Ethics

Ethical considerations were given to the fact that participants may share sensitive information on the person cared for without this person having the means to defend themselves. To ensure unnecessary sharing of information, participants were encouraged to talk solely concerning their own views and the caring situation. The study followed the principles of the Helsinki Declaration (48) and was registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (2015‐57‐0016‐020a). According to Danish law, no ethics committee approval was required (49). All participants gave informed written consent to participate and were anonymised by giving all participants a unique number in the transcribed material. Secure storage of all personal data followed the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Hence, documents and audio and text files were stored in a safe or on a secure server with a code and a log of access.

Results

Content analysis of carers views complemented by professionals views on carers’ support needs resulted in four main categories: (i) carers’ support needs in daily life when caring for a person with dementia, (ii) carers’ support needs to focus on themselves, (iii) carers’ support needs to maintain own well‐being and (iv) carers’ support needs to communicate and interact with surroundings (see Fig. 2).

The demographics of participants illustrate the heterogeneity of both carers and professionals regarding age, progression of dementia, relationship (carer) and experience (professional) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of participants in the interviews (focus group and individual)

| Carers (n = 23) | Professionals (n = 13) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 15 | Gender (female) | 13 | ||

| Mean age (range) | 64.7 (34–83) | Mean age (range) | 47.8 (31–62) | ||

| Relationship | Wife | 6 | Education | Nurse | 4 |

| Husband | 6 | Therapist | 2 | ||

| Daughter | 5 | Social care or healthcare assistant | 5 | ||

| Son | 2 | Social care or health service helper | 2 | ||

| Daughter‐in‐law | 1 | Mean experience in years (range) | 14.4 (3–30) | ||

| Sister | 2 | ||||

| Friend | 1 | ||||

| Cohabiting | Yes | 13 | |||

| No | 10 | ||||

| Employment | Retired | 15 | |||

| Employed | 4 | ||||

| Unemployed | 3 | ||||

| Sick leave | 1 | ||||

| Diagnosis of cared‐for person | Alzheimer’s | 16 | |||

| Vascular | 1 | ||||

| Other | 5 | ||||

| Don’t know | 1 | ||||

| Stage of disease | Mild | 3 | |||

| Moderate | 9 | ||||

| Severe | 9 | ||||

| Deceased | 2 | ||||

| Care service for the person with dementia | No use of care | 2 | |||

| Home care | 11 | ||||

| Nursing home | 8 | ||||

Carers’ support needs in daily life when caring for a person with dementia

Carers’ support needs in daily life involves adjusting offered formal care to the overall situation of both the carer and the person cared for. Additionally, carers need continuous access to knowledge in how to deal with symptoms of dementia.

Need for support to care for a person with dementia

Carers express worries and struggles when dealing with dementia in daily life but not for managing practical care issues, for example cleaning or helping the person with dementia get dressed. A carer describes how she finds the practical day‐to‐day tasks easy to manage:

Anyway, regarding the practical issues of caring, I am quite good at dealing with what has to be done. (Friend P2)

In contrast, professionals describe how they focus on carers needs for practical support in day‐to‐day tasks:

It is obvious that we support managing household chores in accordance to our service level…but for …gardening we can't provide any help. We only offer personal care'. (Professional P27)

Though well‐intentioned offered supportive services may not be the kind of support, carers need the most. Regarding needed support, carers describe that caring consumes their thoughts around the clock. They need to know the person with dementia is safe and is offered appropriate activities. Carers call for someone to share the responsibility of ensuring the well‐being of the person with dementia living at home, because it is not possible to be present all the time. A daughter describes how she comes to the person with dementia’s rescue:

Now she only lives one and a half kilometres from me, which is easy…but…before she lived seventeen kilometres away and…sometimes…well, things happened and then the next. And she was so sad. And then I had to go all this…way just to find out it was nothing special… (Daughter P4)

Carers express how consuming it is to be constantly on guard. To avoid having to put their own plans on standby, they need support to secure the well‐being and safety of the person with dementia.

When providing formal support to comply with carers’ needs, both professionals and carers agree upon the need for flexible solutions that correspond to both the support needs of the person with dementia and those of the carer. A professional says:

You have to be careful not to take something away from them that they would have liked to do themselves. (Professional P26)

Supportive interventions may be more helpful when the carers’ situation is taken into account.

Need for support to get knowledge on caring

A common need among carers is easy access to knowledge of how to deal with symptoms. Many carers describe uncertainty about what is the best thing to do when caring for a person with dementia. Carers express wanting to care for the person with dementia, but they need support in how to care. A daughter says how she needs support to feel confident in the carer role:

I just feel…that I am going around in the dark and… am I doing it right?...Well, I did not know that there was a Dementia Clinic I could turn to. (Daughter P4)

The type of knowledge carers need is how to act in everyday life and to understand what common behaviour is, when living with dementia. A professional explains how she experiences carers calming down when they know what to expect:

When they hear it is not uncommon that you may act like this or that, and that it is normal to be distrustful. A lot of things are common thing when you have a dementia disease….Then they calm down and say well, okay, then it’s just the way it is. (Professional P32)

The need for knowledge continues throughout the progression of the condition. Although information on dementia is important at the time of diagnosis, the need for knowledge continues as the disease and the challenges in daily life progress. Carers experience that the information provided often would have been of use much earlier and not only at the time of diagnosis.

Carers’ support needs to focus on themselves

In general, carers describe needs for support that focuses on their own situation. Carers feel that they suppress talking about difficult issues, thereby preventing themselves from finding solutions.

Need for support to get help for myself

Carers seem to experience difficulties acknowledging a need for help for themselves as opposed to getting help for the person with dementia. A professional carer explains:

Often, I actually experience that informal carers find it hard to express their own needs because they are so deeply into caring. Then we have to go in and help them…figure it out. (Professional P26)

Caring is new to most carers, and even though it is to be expected that carers take responsibility for their own well‐being, they are overwhelmed by the complexity of caring. Carers do not ask for help if they are unaware of their own needs or they do not have the strength to act on them. A daughter expresses:

Just the thought of me getting help for myself…I haven’t thought of it…though it would have been fantastic. (Daughter P5)

Carers may not recognise their own needs because they do not know that this is a possibility. They suppress their own needs because they are constantly aware of the person with dementia’s needs. A carer says:

I think I know his needs better than my own. (Ex‐wife P18)

Carers’ lack of ability to acknowledge own needs constitutes a need for support to help differentiate the carer’s needs from the person with dementia’s needs, and carers need to be acknowledged by professionals. Often carers describe that they feel as if they are not seen or heard by anyone, and the person with dementia gets all attention. A carer describes:

I feel very alone…Sometimes I would have liked to talk about how I am doing? (Wife P13)

Carers portray a reality with little focus on carers’ needs. A change of attitude is called for among carers and professionals if carers’ support needs are to be identified.

Need for support to talk about difficult issues

Carers explain that some issues are difficult to talk about, and they need help to confront sensitive issues such as intimacy, violence and death. Notably, talking about death is tabooed. When asked, carers describe a heartfelt need for someone to help them confront this issue and to prepare for the future. A carer explains:

I missed some knowledge, right? I can see my mother getting worse and worse. And how am I to tackle this? (Son P6)

When no one confronts tabooed issues, carers are left alone dealing with the dire consequences of the disease – emotionally and practically. Also, these issues are difficult for professionals to uncover. A professional says:

He [the person with dementia] had started having hallucinations…my colleague was there and she sensed…something…but she couldn’t quite tell. So she left. Suddenly she heard a sound…she went back and saw that he had pushed her, causing her arm to fracture. (Professional P35)

As this example express, carers need emotional and practical support to handle difficult issues when caring because of the carers’ unlimited compassion and patience towards the person with dementia.

Carers’ support needs to maintain own well‐being

Carers say their emotional well‐being depends on a strong relationship with the person with dementia or someone else. They also call for opportunities to maintain physical well‐being by being physically active.

Need for support to handle emotional burden

Most carers feel guilty for not doing enough. Carers describe a need for forgiveness from the person with dementia, their surroundings and themselves. A carer describes:

I feel a bit…stuck. I may say I have a thing today, so I’m not coming over and that’s fine…but this feeling of bad conscience; it…goes on in the back of my head. (Daughter P4)

Carers express that they feel inadequate, which makes it difficult to achieve success in the caring role. The relationship with the person may suffer from this, and carers need help to preserve positive interactions with the person with dementia. A professional explains:

Many carers express that they focus on all of those nice experiences together and they often find it hard to organise themselves. (Professional P30)

When carers impose themselves with thoughts of not doing enough, caring may become an emotional burden. Carers describe that they need help to feel connected to the person with dementia and to preserve the relationship without feeling inadequate. A carer describes how keeping up singing together with the person with dementia is a positive experience to him:

We have that joy of singing in a choir…and I am so fortunate that three friends have offered to be there when my wife can't go anymore…if you leave a choir you lose a great community. Music really helps me. (Husband P17)

However, this carer prepares for a time when they will not be able to sing together, which he cannot do in good conscience unless someone helps him to this.

Furthermore, carers describe feeling alone because the illness prevents sharing their feelings with the person with dementia. A carer describes how he by chance has found comfort:

I told him as it was, even though it was harsh. A friend’s wife got the Alzheimer’s disease two years after my wife. It was my damn luck. Now we have each other to talk to. (Husband P20)

Carers have a need for support to find someone to share their feelings with because they feel too vulnerable to pursue emotional support on their own.

Need for support to achieve physical well‐being

Carers describe that they find it hard taking care of their own physical well‐being. Carers suppress signals of stress and strain. A wife says:

I just passed out driving in my car…I thought I was fine. But I wasn’t. (Wife P13)

This carer points to the issue that carers may not be able to identify whether their body is exhausted, thus leaving carers with a need for help to recognise their own physical limitations. Carers describe how they receive well‐intentioned concern from the surroundings but with no backup of action. A carer says:

I hate it when someone tells me to take care of myself. I could just hit them…You don’t know how to do that? (Ex‐wife P18)

When carers explain what makes it hard taking care of themselves, they emphasise that they do not have the extra energy after having cared for the person with dementia. A carer says:

Something’s gotta give. It has taken a toll…in the end it has taken so much, that your own needs is the only thing you have to give away. (Son P3)

Carers do not feel as if they have a choice of prioritising own well‐being over the person with dementia. Consequently, carers have a need for someone to help look after themselves. Carers feel responsible for the person with dementia and neglect their own physical well‐being. Several carers describe that no one takes their health seriously, not even themselves, because everything revolves around the person with dementia. A way of prioritising carers’ health is for example by enabling physical activity to offload and reconnect with themselves. A carer explains:

Now I go for long runs. And I found out that trees don’t talk back. So I let my anger go just by yelling and screaming. Getting rid of my frustrations. (Son P3)

Carers find that physical activity is a way to take care of oneself and to focus on something other than caring. Carers experience that respite care is often too rigid to comply with the varying needs of carers to maintain their own physical well‐being.

Carers’ support needs to communicate and interact with surroundings

Communication and interaction with one’s surroundings are very challenging, and carers need help to mobilise close network, as well as representatives of the system.

Need for support to communicate and interact with family, network and professionals

Carers describe a need to involve family, friends or other closely related persons in care. They feel obligated to make decisions on behalf of the person with dementia though feeling insecure. A daughter describes how she feels forced to make decisions:

When a decision had to be made…on behalf of my father, they came to me and not my brother. (Daughter P1)

Carers indicate a need for support to involve the person with dementia or this person’s closest network in decision‐making, which represents a risk of starting a conflict due to different expectations about responsibility and degree of involvement. A professional describes how she witnesses disagreements:

Well, a lot of them experience that they do not get the necessary support from the family. (Professional P31)

Carers have a need for support to involve the close network in daily care. When carers feel supported in caring, they find daily living easier.

Further, carers describe that communication with professionals is important, and carers need to get day‐to‐day information about the well‐being of the person cared for. A carer says:

And that’s what I think is missing, that they contact you and tell how it is going; that there has been someone to check up on her…But I 'always have to ask. (Sister P9)

Caring is less problematic when professionals share knowledge and plans for formal care. This provides carers with reassurance that the person with dementia is well and the best course of action is taken – otherwise carers have to take action. Carers express that they need to be acknowledged and involved when professionals decide on treatment or care for the person with dementia.

Another area of need for support is how carers communicate and get information and support from different public institutions, for example citizen service centres, hospitals and banks. Attaining relevant knowledge is vital to manage the uncertain future of the person with dementia and themselves. A daughter describes having many questions about the future:

Regarding financial situation, well what is the future gonna look like for her? What about the house she lives in? What is going to happen when she can no longer live there? (Daughter P5)

Carers point to a support need of where to find answers to their questions. Carers deal with problems not only related to the person with dementia’s health but also their citizen rights, insurance and financial issues. Both carers and professionals express that carers have a strong need for support and guidance to manage these problems – problems that go beyond legislative areas and institutions.

Discussion

When developing a new instrument, multiple steps of investigations are needed, including qualitative investigation of the target population and experts’ perspectives on the phenomenon in focus (40). Based on the mutual perspectives among a heterogeneous group of professionals and carers to persons with dementia, this qualitative study has identified four main categories of carers’ support needs that may inform future development of an assessment instrument: (i) carers’ support needs in daily life when caring for a person with dementia, (ii) carers’ support needs to focus on themselves, (iii) carers’ support needs to maintain own well‐being and (iv) carers’ support needs to communicate and interact with surroundings. Our findings also reveal that carers have support needs in common regardless of the relation to the person with dementia and that support needs emerge in the context of caring, which is influenced by carers experience of caring and different expectations to the caring role. Studies have shown that success in the caring role may depend on carers finding meaning in this (50, 51) assisted by positive experiences and high‐quality relationship with the person cared for (23, 51, 52). Also, for some carers the caring role comes more natural. For example, close kinship and co‐residence indicate higher motivation (53) and greater chance succeeding in the caring role (54). However, inconsistency regarding the influence of factors such as gender and spousal or child relationship on caregiver burden confuse this picture (41, 55, 56), which may support our finding that carers have support needs in common regardless of relation, suggesting the importance of individual assessment.

Our most distinctive finding is that carers tend to focus on the needs of the person with dementia, thus not knowing their own needs. Caring for a person with dementia has been described as more burdensome than caring for other chronic illness (5), which may be enhanced by not recognising their own need for support. One explanation could be that articulation of needs is difficult. A mixed‐method study found that carers may express a support need, but they are not able to articulate their actual felt needs (19). Carers neglecting their own needs may also be explained by the paradox that even though carers are in need of support, they may only be able to recognise their own needs for support in retrospect (57). Being able to recognise your own needs can be argued as being part of a transition process (58). Carers may not have the ability to acknowledge how demanding the situation is to themselves, and they may not be able to recognise their own support needs until they have come to terms with how the dementia disease affect themselves even in the early stages of caring (24, 57). In addition, it is paramount that professionals identify carers’ support needs in a timely manner, as minor problems may accumulate and spin out of control without carers realising it (57).

Another significant finding of carers’ support needs is related to the degree of effort needed to sustain the well‐being of the person with dementia. Carers, irrespective of relation, cohabitation status and gender, experience that constantly being attentive of the well‐being of the person cared for takes up most of their time. Especially when the person cared for is living in his or her own home, carers describe an extraordinary feeling of responsibility towards the person with dementia, and they are willing to jeopardise their own well‐being for the benefit of this person. Closely aligned to this, a review has shown that time spent caring and carers’ feeling of preparedness for caring have an important influence on carers’ support needs (41). If carers spend most of their time caring but do not feel prepared, they find it hard to manage the responsibilities of caring (59).

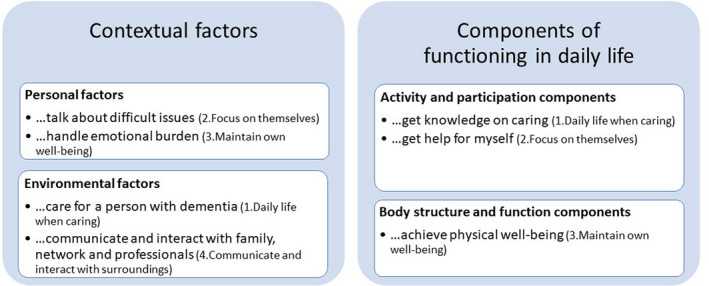

Findings in our study indicate that multiple dimensions of the caring situation influence carers’ need for support including carers own beliefs and experience of caring and also different expectations to the caring role. The biopsychosocial model introduced earlier embrace this complex interaction when identifying needs for support to achieve physical, psychological or social well‐being without defining illness or disability as solely defined by a diagnose (33). Reflecting upon the multidimensionality of the four categories of support needs identified, we introduce the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) founded in the biopsychosocial model (60). The ICF is conceptualised into three main components of functioning (body functions/structure, activity and participation) and two contextual factors (environmental and personal). The ICF provides a dynamic framework to understand what is important to carers’ daily functioning. Within this framework, it is possible to categorise physical, psychological and social aspects of carers’ support needs to maintain daily functioning (18, 61). The transferability of the support needs identified in our study may be illuminated when considering that carers’ support needs are represented across all areas of this framework (18, 62). In Fig. 3, we have linked the four main categories to the ICF by the generic categories in the content analysis (61). The linking shows that all categories are relatable to the ICF framework and that each generic category can be explained by a component or factor within the ICF framework. For example, the generic category '…get help for myself' is included in the Activity and Participation component 'Self‐care' in the ICF, and it allows support needs in relation to this to be addressed on equal footing with more traditionally acknowledged needs defined by the aetiology of a disability (63). In many ways, the ICF provides a holistic framework to classify carers’ support needs, though further research is needed to confirm if the model is applicable.

Figure 3.

Linking main and generic categories to the ICF framework

Also, integrated in the ICF framework is that needs change over time influenced by the environment (25, 63). Although findings in our study are based on carers and professionals views on carers’ support needs throughout the disease trajectory, no close link was found to the progression of the dementia disease in itself. Several studies suggest that carers have their own experience of the progression of the disease (24, 64, 65), and their support needs may more likely relate to this. Carers are continuously faced with new challenges in the caring situation, and they repeatedly go through a process of having to acknowledge and adjust to a new situation because of the progression of the disease (24, 64). Professionals need to know that carers’ support needs change dependent on where they are at in such a process and needs assessment considering this should precede any supportive services offered.

Findings in our study are in line with other studies investigating carers’ needs in end‐of‐life care (20, 66, 67), which suggest that carers in general are in need for support to provide the best care. However, specific to dementia carers are their need for support to balance own needs in relation to the person with dementia (20). Considering whether our findings are specific to dementia, other studies investigating dementia carers’ support needs show a resemblance to the four categories presented. Pini et al. have developed a framework to describe carers’ needs (66) that highlight the relational aspects of carers’ needs. Their categories 'take care of myself' and 'share/express my thoughts and feelings' (66) are very similar to the generic categories 'get help for myself' and 'talk about difficult issues' in our study. In both Pini et al.’s (66) and our study, carers’ support needs develop in relation to high commitment to the person with dementia and not being understood by surroundings, which puts carers in a vulnerable position. Further, Wancata et al. identify 18 problem areas for carers to a person with dementia, and they resemble to the support needs identified in our study (13). Particularly, their problem areas regarding the lack of information about dementia, treatment and services are in line with our findings of carers’ need of knowledge. Using the ICF framework to ensure a holistic approach that also addresses the influence of the environment, the main categories in our study stand out from other studies by including all of the support needs identified in the empiric results and existing literature and framing them in a familiar way for health and social care (31). Hence, the main categories identified in our study may not be new per se, but the heterogeneous sampling of carers has made it possible to include multiple and nuanced perspectives of carers’ support needs. The categories are likely to embrace carer’s whole life situation regardless of relation to the person cared for, context and progression of dementia, which is important when developing an instrument to guide the multidimensional assessment of carers’ support needs. On that account, next step involves a systematic process of item generation based on knowledge from our study in combination with a review of the literature followed by systematic pilot and field‐testing of the new instrument in the target population (40).

Limitations

Though one third of carers in our study were men, most participants were female or spouses. A pattern of high representation of females or spouses is also seen in other studies (66). Even though the key professionals recruiting participants were aware of the importance of a heterogeneous sampling of carers, it may have been difficult to recruit other types of carers. However, a national survey in Denmark shows that women in general are more likely to take on the caring role, which leads to a naturally larger group of female carers (68). Female carers have been seen to experience higher burden and report more health problems than male carers (69). This may be due to female carers’ use of an emotion‐focused coping strategy that may not be the most effective (41). Findings in our study may therefore represent more emotion‐focused needs.

A limitation to recruitment of participants is that the majority of carers reported caring for a person with moderate to severe dementia, which may have forced carers to take more responsibility in their relationship with the person with dementia (70). Research have shown that relationship quality is important to carers’ motivation and positive experience of caring (23, 51), and important differences in carers’ support needs in relation to severity of the disease and the person with dementia’s disabilities may have been disregarded. Another limitation to our recruitment strategy is a lack of focus to include carers with a minority ethnic background. This group have previously been described to have support needs different from the majority due to a poor understanding of what supportive services provide (71), and when developing an assessment instrument their perspective on support needs may not be fully considered.

A possible bias in the study is the text cards used in the interviews to prompt participants’ discussion of support needs. To consider this bias, participants were also given blank text cards to encourage discussing support needs not described (35). Most participants made use of this option, which suggests that the four main categories in our study represent participants own thinking of carers’ support needs. As an example, the need for support to talk about death and violence were topics brought up by carers themselves. Hence, we consider it unlikely that the use of text cards has biased our findings.

Analysing qualitative data is sensitive to subjective interpretation (47). To enhance the credibility of our interpretation of the data, coding, creating categories and abstractions followed the rigorous process of analysis described by Elo and Kyngäs (47) involving continuously dialogue between all authors. Within content analysis, two different approaches of interpretation exist: latent and manifest (47). We have chosen to use manifest interpretation, where categories can be identified as a thread throughout the codes. However, interpretation with a manifest approach has a descriptive purpose and entail that all content is reflected in exhaustive and mutually exclusive categories. This feature is important when conducting the next step in developing an assessment instrument, because dimensionality of an instrument depends on items belonging to only one dimension of the construct of interest (40). Also, supporting trustworthiness of our findings is that no new categories emerged in the individual interviews following focus group interviews and that the same codes emerged over and over again across the entire data material, suggesting saturation in the clarification of categories of carers’ support needs (72).

Implications

Carers contribute significantly to the well‐being of the person with dementia, and carers may need support when caring. However, carers to a person with dementia may not acknowledge or articulate their support needs, stressing that assessment of carers’ support needs should be a focus in future dementia care. Carers describe receiving inadequate support, and new ways to address carers’ support needs have to be developed. A new approach may be developing an instrument that facilitates dialogue between carers and professionals to help carers acknowledge and articulate their support needs in a timely manner. When developing a new assessment instrument, several steps of investigations are needed to generate items and ensure robust psychometric properties. The four main categories identified in our study may inform a foundation for item generation when developing such an instrument to improve carer support in dementia social and health care.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Health Sciences Research Centre at UCL University College Denmark; the Danish Alzheimer Association; and the Association of Danish Physiotherapists.The authors would like to thank all participants, our contact persons and the management in the municipalities of Odense and Svendborg, Denmark.

Scand J Caring Sci;2021; 35: 586–599 “I know his needs better than my own” – carers’ support needs when caring for a person with dementia

References

- 1. Medical directorate and Nursing directorate . NHS England’s commitment to carers. NHS England. May 2014.

- 2. World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International . Dementia: a public health priority. 2012;ISBN: 978 92 4 156445 8.

- 3. Farina N, Page TE, Daley S, Brown A, Bowling A, Basset T, Livingston G,Knapp M, Murray J, Banerjee S. Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement 2017; 13(5): 572‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jorgensen K, Waldemar G.The prevalence of dementia in Denmark. Ugeskr Laeger 2014 Nov 24;176(48). [PubMed]

- 5. Schulz R, Sherwood PR. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am J Nurs 2008; 108(9 Suppl): 23–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roehr S, Pabst A, Luck T, Riedel‐Heller SG. Is dementia incidence declining in high‐income countries? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Epidemiol 2018; 18: 1233–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schulz R, Martire LM. Family caregiving of persons with dementia: prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. Am J Geriatric Psychiat 2004; 12: 240–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meaney AM, Croke M, Kirby M. Needs assessment in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 20: 322–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brodaty H, Thomson C, Thompson C, Fine M. Why caregivers of people with dementia and memory loss don't use services. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 20: 537–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Novais T, Dauphinot V, Krolak‐Salmon P, Mouchoux C. How to explore the needs of informal caregivers of individuals with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease or related diseases? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMC Geriatr 2017; 17: 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mansfield E, Boyes AW, Bryant J, Sanson‐Fisher R. Quantifying the unmet needs of caregivers of people with dementia: a critical review of the quality of measures. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017; 32: 274–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Durme T, Macq J, Jeanmart C, Gobert M. Tools for measuring the impact of informal caregiving of the elderly: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 2012; 49: 490–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wancata J, Krautgartner M, Berner J, Alexandrowicz R, Unger A, Kaiser G, Marquart B,Weiss M. The Carers' Needs Assessment for Dementia (CNA‐D): development, validity and reliability. Int Psychogeriatr 2005; 17(3): 393‐406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reynolds T, Thornicroft G, Abas M, Woods B, Hoe J, Leese M, Orrell M.Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE). Development, validity and reliability. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176: 444‐452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mosquera I, Vergara I, Larranaga I, Machon M, Del Rio M, Calderon C. Measuring the impact of informal elderly caregiving: a systematic review of tools. Qual Life Res 2016; 25: 1059–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgs J. Clinical Reasoning in the Health Professions, 3rd edn. 2008, Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh; New York. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bangerter LR, Griffin JM, Zarit SH, Havyer R. Measuring the needs of family caregivers of people with dementia: an assessment of current methodological strategies and key recommendations. J Appl Gerontol 2019; 38: 1304–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dean SG, Siegert RJ, Taylor WJ. Interprofessional Rehabilitation: A Person‐Centred Approach. 2012, Wiley‐Blackwell, Chichester, West Sussex, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stirling C, Andrews S, Croft T, Vickers J, Turner P, Robinson A. Measuring dementia carers' unmet need for services‐an exploratory mixed method study. BMC Health Serv Res 2010; 13: 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCabe M, You E, Tatangelo G. Hearing their voice: a systematic review of dementia family caregivers' needs. Gerontologist 2016; 56: e70–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bunn F, Goodman C, Sworn K, Rait G, Brayne C, Robinson L, McNeilly E, Iliffe S. Psychosocial factors that shape patient and carer experiences of dementia diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS Med 2012; 9(10): e1001331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jacobson J, Gomersall JS, Campbell J, Hughes M. Carers' experiences when the person for whom they have been caring enters a residential aged care facility permanently: a systematic review. JBI Database systematic Rev Implement Rep 2015; 13: 241–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quinn C, Clare L, Woods RT. Balancing needs: the role of motivations, meanings and relationship dynamics in the experience of informal caregivers of people with dementia. Dementia (London) 2015; 14: 220–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clemmensen TH, Busted LM, Søborg J, Bruun P. The family’s experience and perception of phases and roles in the progression of dementia: An explorative, interview‐based study. Dementia 2016; 2016: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hjortbak BR . Rehabiliteringsforum Danmark editors. Challenges to rehabilitation in Denmark. Aarhus: Rehabiliteringsforum Danmark; 2011.

- 26. Hellstrom I, Hakanson C, Eriksson H, Sandberg J. Development of older men's caregiving roles for wives with dementia. Scand J Caring Sci 2017; 31: 957–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Egilstrod B, Ravn MB, Petersen KS. Living with a partner with dementia: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of spouses' lived experiences of changes in their everyday lives. Aging Ment Health 2019; 23: 541–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hennings J, Froggatt K. The experiences of family caregivers of people with advanced dementia living in nursing homes, with a specific focus on spouses: A narrative literature review. Dementia 2019; 18: 303–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Busted LM, Nielsen DS, Birkelund R. The experience of being in the family of a person with early‐stage dementia‐a qualitative interview study. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc 2019; 7: 145–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Piersol CV, Canton K, Connor SE, Giller I, Lipman S, Sager S. Effectiveness of interventions for caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease and related major neurocognitive disorders: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther 2017; 71: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wade DT, Halligan PW. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin Rehabil 2017; 31: 995–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wade D. Rehabilitation–a new approach. Overview and Part One: the problems. Clin Rehabil 2015; 29: 1041–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977; 196: 129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Parkinson M, Carr SM, Rushmer R, Abley C. Investigating what works to support family carers of people with dementia: a rapid realist review. J Public Health 2017; 39: e290–e301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hennink MM. International Focus Group Research: A Handbook for the Health and Social Sciences. 2007, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seale C. Quality in qualitative research. Qual Inq 1999; 5: 465–478. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd edn. 2014. . Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62: 107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62(2): 228–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. de Vet HC, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL. Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide. 2011, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008; 20: 423–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sundhedsstyrelsen . Center for Evaluering og Medicinsk Teknologivurdering. CEMTV. Udredning og behandling af demens ‐ en medicinsk teknologivurdering. København: Sundhedsstyrelsen; 2008.

- 43. Stalmeijer RE, Mcnaughton N, Van Mook WN . Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Med Teach 2014; 36: 923–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Colucci E. “Focus groups can be fun”: The use of activity‐oriented questions in focus group discussions. Qual Health Res 2007; 17: 1422–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Queluz FN, Kervin E, Wozney L, Fancey P, McGrath PJ, Keefe J. Understanding the needs of caregivers of persons with dementia: a scoping review. Int Psychogeriatr 2019; 10: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, 3rd edn. 2013, SAGE, London; Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004; 24: 105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. World Medical Association . World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013; 310: 2191–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ministry of Health and the Elderly . Komitéloven. Bekendtgørelse af lov om videnskabsetisk behandling af sundhedsvidenskabelige forskningsprojekter. LBK nr. 1083 15/9/2017. Lovtidende A 2017 22‐09‐2017;LBK nr 1083 af 15/09/2017(European legislation identifier /eli/lta/2017/1083).

- 50. McGovern J. Couple meaning‐making and dementia: challenges to the deficit model. J Gerontol Soc Work 2011; 54: 678–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Quinn C, Clare L, McGuinness T, Woods RT. The impact of relationships, motivations, and meanings on dementia caregiving outcomes. Int Psychogeriatr 2012; 24: 1816–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hellström I, Nolan M. Lundh U. Sustaining `couplehood': Spouses' strategies for living positively with dementia. Dementia 2007; 6: 383–409. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Quinn C, Clare L, Woods RT. The impact of motivations and meanings on the wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr 2010; 22: 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cherry MG, Salmon P, Dickson J, Powell D, Sikdar S, Ablett J. Factors influencing the resilience of carers of individuals with dementia. Rev Clin Gerontol 2013; 23: 251–66. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tatangelo G, McCabe M, Macleod A, Konis A. I just can't please them all and stay sane: Adult child caregivers' experiences of family dynamics in care‐giving for a parent with dementia in Australia. Health Soc Care Community 2018; 26: e370–e377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Teahan Á, Lafferty A, McAuliffe E, Phelan A, O'Sullivan L, O'Shea D et al Resilience in family caregiving for people with dementia: A systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018; 33: 1582–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Boots LM, Wolfs CA, Verhey FR, Kempen GI, de Vugt ME. Qualitative study on needs and wishes of early‐stage dementia caregivers: the paradox between needing and accepting help. Int Psychogeriatr 2015; 27: 927–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kralik D, Visentin K, Van Loon A. Transition: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 2006; 55: 320–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Veld Huis In Het, JG, Verkaik R, Mistiaen P, van Meijel B, Francke AL.. The effectiveness of interventions in supporting self‐management of informal caregivers of people with dementia; a systematic meta review. BMC Geriatr 2015; 11: 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. World Health Organization . ICF ‐ International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- 61. Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J, Prodinger B. Refinements of the ICF Linking Rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil 2016; 41: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ohman A. Qualitative methodology for rehabilitation research. J Rehabil Med 2005; 37: 273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. World Health Organization . How to use the ICF: A practical manual for using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 2013;October.

- 64. Willoughby J, Keating N. Being in control: the process of caring for a relative with Alzheimer's Disease. Qual Health Res 1991; 1: 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wilson HS. Family caregivers: the experience of Alzheimer's disease. Appl Nurs Res 1989; 2: 40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pini S, Ingleson E, Megson M, Clare L, Wright P, Oyebode JR. A Needs‐led framework for understanding the impact of caring for a family member with dementia. Gerontologist 2018; 58: e68–e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ewing G, Grande G. National Association for Hospice at Home. Development of a Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for end‐of‐life care practice at home: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 244–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. The Danish Alzheimer Association . Living with dementia. Report of a survey among informal caregivers to a person with dementia in Denmark. 2018;February.

- 69. Pillemer S, Davis J, Tremont G. Gender effects on components of burden and depression among dementia caregivers. Aging Ment Health 2018; 22: 1162–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ericsson I, Kjellström S, Hellström I. Creating relationships with persons with moderate to severe dementia. Dementia 2013; 12: 63–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Johl N, Patterson T, Pearson L. What do we know about the attitudes, experiences and needs of Black and minority ethnic carers of people with dementia in the United Kingdom? A systematic review of empirical research findings. Dementia (London) 2016; 15: 721–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B et al Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018; 52: 1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]