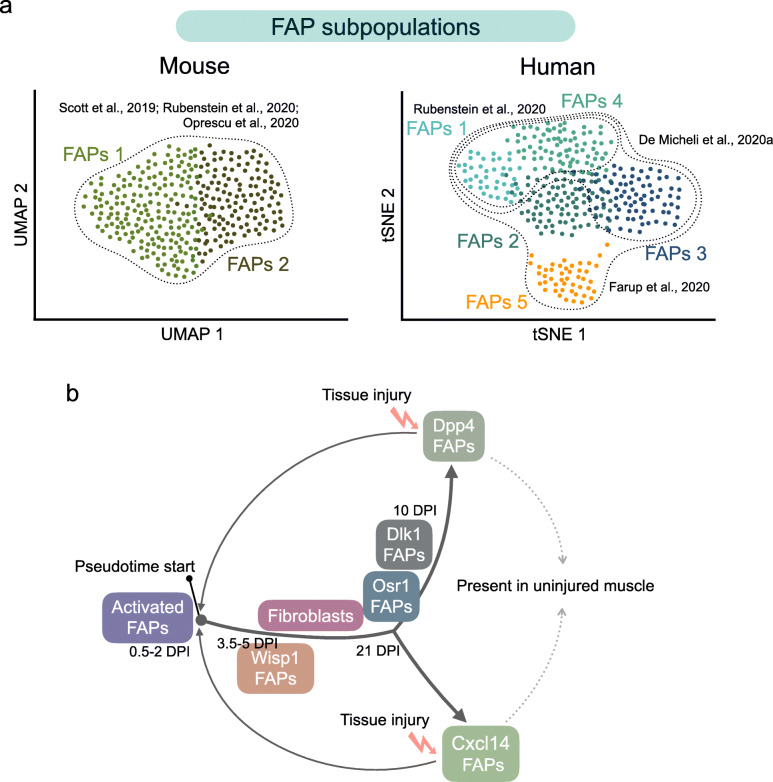

Fig. 3.

a Single-cell RNA sequencing analyses to map muscle-resident FAP mononuclear landscape in murine (left graph) and human (right graph) skeletal muscle tissue. Three different studies, utilizing mice, agree with the existence of at least two principal muscle FAP subpopulations (here shown as FAPs 1 and FAPs 2; see text for details). On the other hand, FAP clustering and FAP subpopulations greatly vary in human muscles. Two different bioinformatic techniques for the presentation of large scRNA-seq datasets and their dimensionality reduction are shown: uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) algorithm and t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE). Colored dots represent individual FAP cells. Dotted lines illustrate the different studies discussed in this review. b FAP cell trajectories are based on the gene signatures of single cells following damage [48, 108]. The transcriptomes of FAPs indicate high cellular heterogeneity within the FAP populations in response to injury. In mouse muscles, two major FAP subpopulations (Dpp4 FAPs and Cxcl14 FAPs) are present in homeostatic conditions (for detailed markers, see Table 4). Analysis of the pseudotime trajectory of different FAP subpopulations suggests that FAP cells follow a continuum and diverge into two major subclusters upon damage