Abstract

Objectives

Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic became the greatest public health challenge globally. Study of dynamicity and durability of naturally developed antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 are of great importance from an epidemiological viewpoint.

Methods

In this observational cohort study, we have followed up the 76 individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) for 16 weeks (post-enrolment) to record the periodic changes in titre, concentration, clinical growth and persistence of naturally developed SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. We collected serum samples from these individuals for 16 weeks with a frequency of weekly and fortnightly during each follow-up and tested them in two CLIA-based platforms (Abbott Architect i1000SR and Roche Cobas e411) for testing SARS-CoV-2 antibodies both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Results

We recorded the antibody magnitude of these individuals 10 times between September 2020 and February 2021. We found a waning of antibodies against nucleocapsid antigen protein but not a complete disappearance by the end of 16 weeks. Out of 76 cases, 30 cases (39.47%) became seronegative in qualitative assay, although all the sera samples (100%) remained positive when tested in quantitative assay.

Conclusion

The lower persistence of anti-nucleocapsid SARS-CoV-2 antibody may not be the exact phenomenon as those cases were still seropositive against spike protein and help in neutralising the virus.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s15010-021-01651-4.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Nucleocapsid protein, Spike protein, IgG, COVID-19

Introduction

Since its emergence in December 2019, from Wuhan city of China, SARS-CoV-2 virus has spread rapidly throughout the world. As of April 12, 2021, more than 135 million individuals were infected with SARS-CoV-2 and 2.92 million SARS-CoV-2-associated deaths were reported [1]. USA, India, and Brazil account for most of the cases worldwide with India recording about 13.52 million cases and 1.70 million deaths [1, 2].

In general, antibodies are known to play an important role in neutralising the virus and provide protection to the host against re-infection. Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 can target many of its encoded proteins, including structural and non-structural antigens. Thus far, two structural proteins have been used as target antigens for serological assays for SARS-CoV-2. One is the abundant nucleocapsid protein (N), second is the structural spike protein (S) often used as a target for characterising the immune response to SARS-CoV-2. However, there is limited understanding of antibody responses and persistence post-infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus [3]. Specifically, we lack detailed descriptions and precise estimates concerning the magnitude and duration of responses following the infection. Upon infection, SARS-CoV-2 elicits humoral responses, and within 3 weeks almost all infected patients develop antibodies against the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the S1 and S2 domains of the spike glycoprotein, as well as against the nucleocapsid protein [4]. It is known from other coronaviruses and it holds true for SARS-CoV-2 that the spike is the main, and potentially the only, target for neutralising antibodies [5]. However in-depth knowledge on the magnitude, timing, and longevity of antibody responses after SARS-CoV-2 infection is vital for understanding the role of the antibodies in disease clearance and protection from re-infection and/or disease. Although some studies from Iceland and the USA demonstrated the persistence of antibodies SARS-CoV-2 infection beyond 4 months post-infection, other studies have reported rapid waning of antibodies within 3–4 months [6]. The present study uses periodic samples from 76 individuals with RT-qPCR confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection up to 16 weeks from enrolment into the study to understand the magnitude and durability of the antibody response.

Methods

Study setting

A cohort of 76 confirmed COVID-19 positive healthcare and frontline workers from Bhubaneswar city, India was included in this study. Individuals were enrolled into the cohort after 28 days of being tested positive by RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 virus and were followed up for 4 months with a periodic sample collection. No new or re-infection was reported by the cohort participants during the study period. The study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethical Committee. Informed signed consent was obtained from individuals before their enrolment into the study.

Test method

A 5 mL of blood sample was collected and serum was isolated to evaluate the IgG antibody against N and S-protein antigen. Antibody titre was determined by a commercial qualitative assay using Abbott architect i1000SR (Abbott Diagnostics, Chicago, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay is a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay that detects IgG against the N-protein of SARS-CoV-2. An index (S/C) of ≥1.4 was interpreted as reactive and <1.4 index as non-reactive. The concentration of IgG antibody against RBD of SARS-CoV-2 S-protein in human was determined by Roche Cobas e411 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) which is based on electrochemiluminescence technology for the quantitative detection of antibodies including IgG. A value of <0.80 U/mL was considered as negative and values ≥0.8 U/mL were identified as positive. The individual samples were tested for Ab against N and S-protein after 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th, 8th, 10th 12th, 14th and 16th week of enrolment. At least two consecutive positive samples were tested to classify a participant as seropositive, whereas disappearance of IgG was defined as having at least two negative tests after having been classified as seropositive.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24.0, Armonk, NY) and GraphPad Prism 7.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA) were used for descriptive statistical analyses. p values <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

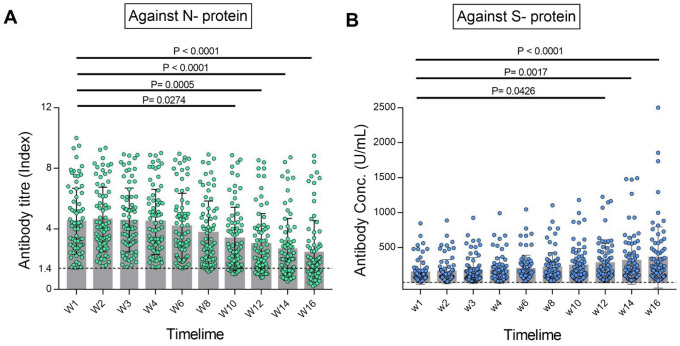

SARS-CoV-2 antibody titres were periodically (10 times) measured in 76 individuals (healthcare and frontline workers) who were COVID-19 positive by RT-PCR. All the 76 study participants had anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies detected at enrolment and the median number of days between confirmation of RT-qPCR positive and serum antibody detection was 24 days. Median antibody titre was measured as 4.19 index (interquartile range [IQR], 2.78–6.03) at week 1 which was started to wane from week 4 and decreased to 1.76 index (IQR 1.00–2.92) at the end of week 16 in qualitative test detecting antibody against N-protein (Fig. 1A). In this cohort, participants from 18 to 63 years were categorised in three different age groups of 18–29 years (n = 31; 34.21%), 30–49 years (n = 19; 25%), 50 years and above (n = 19; 25%). The median age of the participants was 36.5 years (IQR 49.5–26.5) with 51 (67.11%) males and 25 (32.89%) were female. Among 76 participants, 60 (78.95%) were symptomatic during 2 weeks of the symptom onset (Table 1). The most common symptom found was fatigue (n = 58; 76.3%) followed by fever (n = 48; 63.1%) and cold (n = 46; 60.5%) (Fig. S1). Forty-six participants (60.53%) were found to have a reactive level of antibody till 16 weeks, whereas 30 (39.47%) become seronegative against the N-protein of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1A). Seventeen of those seronegative 30 individuals (56.67%) were aged between 18 and 29 years; 8 (26.67%) were aged between 30 and 49 years and 5 (16.67%) were 50 years or older. All the participants (100%) were found positive in quantitative antibody testing at 16 weeks in comparison to 46 (60.52%) in qualitative testing. The median concentration of IgG antibody against S-protein were recorded as 78.38 U/mL (IQR 40.54–161.9) and 212.8 U/mL (IQR 89.2–458.4) at week 1 and week 16, respectively and the increment was statistically significant (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Periodic changes of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies over 16 weeks post-infection. A Titre changes of anti-nucleocapsid IgG as measured by the qualitative Abbott assay. B Concentration changes of anti spike IgG as measured by the quantitative Roche assay. Multiple comparison was done by ANOVA and p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant

Table 1.

Follow-up participants confirmed positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies

| All (n = 76) | Positive for antibodies against N-protein after 16 weeks of follow-up (n = 46) | Negative for antibodies against N-protein after 16 weeks of follow-up (n = 30) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (in years) | 36.5 (IQR 49.5–26.5) | 40.0 (IQR 29.0–52.0) | 27.5 (IQR 25.0–44.0) | 0.017* |

| Age by category (in years) | 0.072 | |||

| 18–29 | 31 (40.79%) | 14 (44.33%) | 17 (56.67%) | |

| 30–49 | 26 (34.21%) | 18 (63.33%) | 8 (26.67%) | |

| 50 and above | 19 (25%) | 14 (83.33%) | 5 (16.67%) | |

| Gender | 0.664 | |||

| Male | 51 (67.11%) | 30 (58.82%) | 21 (41.18%) | |

| Female | 25 (32.89%) | 16 (64%) | 9 (36%) | |

| Infection history | 0.122 | |||

| Symptomatic | 60 (78.95%) | 39 (65%) | 21 (35%) | |

| Asymptomatic | 16 (21.05%) | 7 (43.75%) | 9 (56.25%) | |

*t test significant at p < 0.05 at 95% confidence interval

Discussion

The development of antibody is a common immunological phenomenon constantly happening in our body to give us protection, particularly against the newly invaded immunogens. In the case of COVID-19 infection, the antibody can be detected as soon as the first week from the onset of the symptoms depending on the patients’ immune system [7]. Several studies are ongoing around the world to track down the durability of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG. Some studies have shown that IgG waning is quite fast in COVID-19 although no such study has been done with the Indian population to our best knowledge [6].

In our study, 78.95% (n = 60) participants were identified as symptomatic which is fairly opposite to the symptoms status of general population where most of the individuals (91%) reported as asymptomatic [8]. The present study found around 40% of the serum samples were negative for IgG against N-protein at the end of 4 months, whereas a similar study in USA found only 7.7% SARS-CoV-2 IgG negative after 3–6 months following symptom onset [9]. The males were having higher titre values than females in both qualitative and quantitative testing at the end of 16 weeks although the difference was statistically insignificant. Four (5.26%) of these individuals were hospitalised during the infection period and had developed a high antibody titre and the average was 7.22 index.

Our study showed a considerable difference in the result interpretation between qualitative and quantitative serological assays for COVID-19. In the qualitative assay, antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 was observed to persist for more than 16 weeks with a reduction in antibody levels which can be corroborated by a similar finding from Hubei province [10]. However, all the sera samples from 76 individuals were found to be positive in the quantitative assay platform against S-protein of SARS-CoV-2. The 30 seronegative samples (median antibody titre = 0.905 U/mL; IQR 0.58–1.02) detected in qualitative assay against N-protein gave a median concentration of 95.33 U/mL (IQR 54.8–177.1) after 16 weeks against S-protein. The threshold levels of serum antibody which could prevent re-infection of SARS-CoV-2 is still unknown and needs further research. Moreover, we found a gradual decline in qualitative antibody titre value in 55% of individuals after 16 weeks when compared to week 1. Although antibody to the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 is more sensitive than spike protein antibody for detecting early infection, the waning may be due to the lower detection sensitivity of the SARS-CoV-2 N-protein at post-recovery duration as antibody against N-protein is more sensitive than spike protein for detecting early infection [11]. In the quantitative assay for the same samples, a time-dependent increment of antibody concentration was observed. However, the adaptive humoral immune response against SARS-CoV-2 S-protein may not give the full proof immunoprotection and could be limited as speculation as we do not know the threshold magnitude. We hypothesised that the anomaly between these two assays inference may be for the different target antigen as mentioned in the methodology. We also observed that asymptomatic individuals produced less titre of the antibody as found both in the qualitative and quantitative assay.

In conclusion, these data imply that antibody titre against N antigen protein is waning with time but not completely disappearing. However, the seronegative cases found against N-protein might not be the true negative as those were tested positive for antibody against S-protein antigen which would help in neutralising the virus. Based on the study findings, we recommend to test the presence of antibody against S-protein antigen to confer a final conclusive remark upon the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 antibody in an individual.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all the healthcare workers for their tireless dedication at each level to fight COVID-19 and for voluntarily participating in this cohort study. The authors are thankful to the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi and Department of Health & Family Welfare, Govt. of Odisha for providing financial support for the study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests in any form.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was ethically approved by the institutional human ethical committee of ICMR—Regional Medical Research Centre, Bhubaneswar.

Footnotes

Hari Ram Choudhary, Debaprasad Parai and Girish Chandra Dash are contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Sanghamitra Pati, Email: drsanghamitra12@gmail.com.

Debdutta Bhattacharya, Email: drdebdutta.bhattacharya@yahoo.co.in, Email: drdebduttab.rmrc-od@gov.in.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available at: https://covid19.who.int. Accessed 12 Apr 2021.

- 2.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available at: https://main.mohfw.gov.in. Accessed 12 Apr 2021.

- 3.Huang AT, Garcia-Carreras B, Hitchings MDT, et al. A systematic review of antibody mediated immunity to coronaviruses: kinetics, correlates of protection, and association with severity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4704. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18450-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vabret N, Britton GJ, Gruber C, et al. Immunology of COVID-19: current state of the science. Immunity. 2020;52:910–941. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibarrondo FJ, Fulcher JA, Goodman-Meza D, et al. Rapid decay of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in persons with mild COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1085–1087. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2025179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau EHY, Tsang OTY, Hui DSC, et al. Neutralizing antibody titres in SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Commun. 2020;12:63. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruni M, Cecatiello V, Diaz-Basabe A, et al. Persistence of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in non-hospitalized COVID-19 convalescent health care workers. J Clin Med. 2020;9:3188. doi: 10.3390/jcm9103188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar N, Hameed SK, Babu GR, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Karnataka state, South India: transmission dynamics of symptomatic vs. asymptomatic infections. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;32:100717. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maine GN, Lao KM, Krishnan SM, et al. Longitudinal characterization of the IgM and IgG humoral response in symptomatic COVID-19 patients using the Abbott Architect. J Clin Virol. 2020;133:104663. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Lu S, Li H, et al. Viral and antibody kinetics of COVID-19 patients with different disease severities in acute and convalescent phases: a 6-Month follow-up study. Virol Sin. 2020;35:820–829. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00329-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burbelo PD, Riedo FX, Morishima C, et al. Sensitivity in detection of antibodies to nucleocapsid and spike proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:206–213. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.